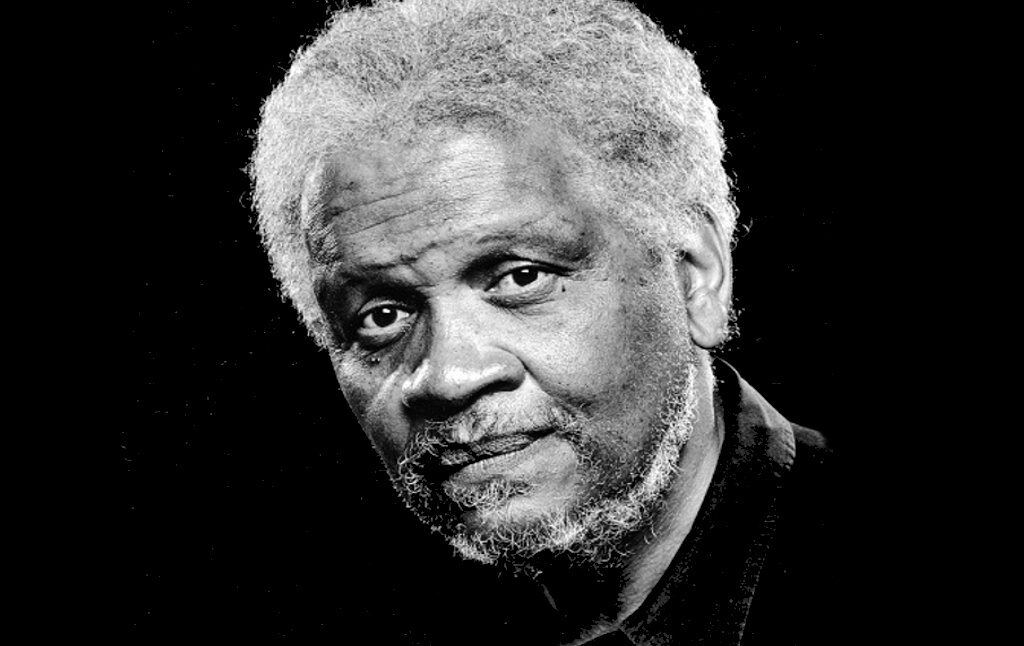

Ishmael Reed Doesn’t Like Hamilton

The celebrated author on his new play, “The Haunting of Lin-Manuel Miranda”…

Look, we already know that Ishmael Reed hasn’t seen Hamilton.

The New York Times called Reed out for it. So did the New Yorker. So did some stray Hamilton stans on Twitter, disgruntled that the legendary playwright, who has written a satire of their beloved play, had the gall to criticize without taking the time to luxuriate in the original, the way they have.

They can all calm down.

“I’ve read the book,” said Reed, who sounded a little surprised that this was even up for debate when I interviewed him a few weeks ago. He’s extensively studied the script that Lin-Manuel Miranda wrote. That’s probably one better than most Hamilton fans, whose familiarity most likely comes through the original soundtrack, have managed to achieve.

“I’ve been criticized for going after this multibillion dollar juggernaut,” said Reed with a laugh. “Well, Gone With The Wind was a global phenomenon as well.” Look how that turned out.

It would be a mistake to underestimate Reed, whose 10th and latest play, The Haunting of Lin-Manuel Miranda, had its first reading at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe on the Lower East Side a few weekends ago. The Haunting rips apart Hamilton, Miranda’s homage to the first Secretary of the Treasury. Reed has been writing literature and non-fiction since the 1960s, and is widely regarded as one of the most important African American authors.

At the showing of The Haunting, which I saw a few weeks ago, Reed included a fundraising plea: If you liked this show and want to see it get a full production, email Reed. Reed’s old-school crowdfunding campaign has mostly worked. He’s raised enough money for The Haunting’s staging. Opening night is May 23rd, and casting is happening now.

Remaining funds are needed for publicity, but promoting the show shouldn’t be a hard task, if the response to the reading itself was any clue. Posts about The Haunting circulated all over Facebook and Twitter, touching a nerve among the sizable number of Hamilton-haters across the internet. Despite the lack of production and the sometimes-stilted acting, the crowd at the show I went to seemed enraptured by the performance, breaking out into peals of laughter at each joke and applauding furiously each time Reed, through the proxy of his actors, got in a particularly spicy jab in at Miranda.

If you haven’t seen Hamilton, here’s what you need to know. The play opens with a scrappy young Alexander Hamilton arriving in New York, ready to take on the world. His goal? To join the raggedy band of upstarts planning revolt against the British Empire. He succeeds in becoming a revolutionary, and survives to reap the fruits of winning a war. Eventually, he gets caught up in messy political machinations, has an extramarital affair, and gets killed in a duel. It’s a whirlwind celebration of a life lived on the edge of what’s possible, at least according to Miranda.

Audiences seem to agree. Hamilton swept the Tonys in 2016. The musical has become famous for its sky-high ticket prices, for selling out every show. Millions of people have seen it. Millions more are going to, as the musical embarks on permanent runs in other cities, as the production completes its regional tours, and as the show eventually becomes available for community theater and school productions. Hamilton just wrapped up a historic (and controversial) run in Puerto Rico, where Miranda’s parents are from, in which Miranda himself reprised his role as Alexander Hamilton for the three-week run. And hundreds of thousands of schoolchildren have seen Hamilton on a heavily-subsidized ticket, thanks to a partnership between the producers and the Gilder Lehrman Institute.

Given all the almost uniformly-positive press that Hamilton has received, the near universal adoration from all acceptable liberal touchstones in American culture (President Obama is a huge fan), why would anyone on the left side of the political spectrum hate this play?

Oh, so many reasons. For one, it’s terrible, as Alex Nichols pointed out in this magazine a little while ago. It’s corny, hokey, and according to my hip hop-head of a boyfriend, the raps are basic as hell. For another—and this is the main reason—its politics are abhorrent. Celebrating the Founding Fathers? Glorifying them as renegades and go-getting revolutionaries? Why, exactly, in 2019, would we want to do that, given all that we know about the horrors committed by these people and in their name?

The horrors I refer to are mainly the near-extermination of America’s native peoples, and of course, slavery. Miranda gets around this problem with a near-unshakable belief in the righteousness of his main character; he has argued in the text of Hamilton that his hero was an abolitionist, a man who hated slavery from childhood. In verse, he berates other Founders for their reliance on unpaid labor, their sloth, their moral ineptitude.

But Reed sees things differently. “I draw attention to what was left of out Hamilton by giving speaking parts to those who were left out of the narrative,” says Reed. In The Haunting, Miranda, possibly high on Ambien, is haunted by ghosts of actual-history past. Through a series of visitors, including former slaves who were leased to Hamilton’s household, white indentured servants, Native American characters, and Harriet Tubman herself, Miranda grows to learn that his source material—historian Ron Chernow’s Alexander Hamilton—is fatally flawed, as it erroneously portrays Alexander Hamilton as a champion of liberty for oppressed people.

“How can someone have slaves and be considered an abolitionist?” Reed asks. The evidence points to the actual Hamilton owning slaves. At the very least, there is very strong evidence that Hamilton leased slaves who were owned by other people. And the family Hamilton married into—the much vaunted Schuylers—were celebrated slave owners. “Schuyler was harsh with his slaves,” says Reed. He is thinking about adding a new character to The Haunting. “There was a runaway from the Schuyler plantation named Diana. She was captured, and no one knows what happened to her after that. There’s a possibility she was murdered,” says Reed. (Reed draws on the scholarship of several women historians, citing Michelle Du Ross, Nancy Isenberg, and Lyra Monterio, for his deep understanding of the lesser-known histories of the Hamilton family.)

Of course, Hamilton has famously sidestepped the question of race by playing a fantastic little trick on the audience: All characters, save King George, are played by people of color, mainly black and Latino actors. To further hammer home the ingenuity, the play is mainly rapped; it is delivered in a mostly non-white musical medium: hip hop.

Reed is not impressed.

“They cast black people in order to defend projects that [black people] might find objectionable,” he says. “It sort of distracts from the racism of the white historical characters.” As for the youthful medium in which the play is delivered: “the producers of this profit-hungry production,” he writes in his CounterPunch critique of Hamilton, “are using the slave’s language: Rock and Roll, Rap and Hip Hop to romanticize the careers of kidnappers and murderers.” The creative effect this casting has is to cast a gruesome history with what scholar Matthew Sekellick labels a “progressive sheen of diversity.”

Reed is less taken with the aesthetics of Hamilton than most audiences and even some critics seem to be. “I can sense that Miranda is obsessed with showtunes,” he says, dismissively. However, Jeremy Gordon at the Outline has criticized The Haunting for being boring, and says an element of theatricality might have served the play’s message better. “Ironically, a better delivery system for why Miranda and his play suck,” writes Gordon, “would have been… a rapped musical.” (For what it’s worth, Reed objects to this criticism; he says that the magnitude of the audience response certainly indicated their disagreement with Gordon’s assessment.)

There is a possible defense for Hamilton’s creative choices. Miguel Cervantes, star of Hamilton’s Chicago production, argues that the play makes history accessible. According to Cervantes, the show is “about real people having real problems, living real lives. It’s being told in this young, fast, hip style.” The function of Hamilton, for Cervantes, is to complicate these formerly lofty historical figures, to bring them down to earth, to humanize them, make them more relatable for young people.

But this argument pisses Reed off. He sees himself as “part of a tradition that challenges any effort to glorify people who were slaveholders and mass murderers.” The most insidious element of Hamilton, for Reed, is the fact that the play takes literal slaveholders and turns them into sympathetic, relatable people, with a veneer of likability. The full and complete history of the revolutionary period, actual black and Native people included, is deeper and frankly, more interesting, than the private intrigues of a few white people at the top.

It’s not the first time that Reed has seen a revisionist retelling of American history in his long career. “Oklahoma!” he tells me. “It was about the conquest of the west. The destruction of Native peoples. And Gone With the Wind was revisionist as well.” And it’s not the first time he’s seen the strategy of using characters or creators of color to deflect criticism from what may ultimately be a racist project. There are parallels, according to Reed, between Hamilton’s brownwashing and the decision to attach Oprah Winfrey as a last-minute producer on the film Precious. (“That’s got to be the worst film ever made about black life,” says Reed. His New York Times op-ed critiquing Precious caused a stir in 2010.)

Despite all this, Reed doesn’t hate Lin-Manuel Miranda. “My play is in fact very sympathetic to Lin,” says Reed. “We want Miranda to back this play. It would redeem him,” Reed told me. He seemed serious. Chances are of course low—no one from the Hamilton camp has reached out to Reed, not even to let him know they appreciate a little well-intended satire—that hasn’t stopped Reed from hoping for a good-faith response.

Reed recently came in for some harsh mockery from Wait Wait Don’t Tell Me!, the beloved (in some quarters) NPR comedy-news quiz show. The host, Peter Sagal, in addition to having no idea who “a writer named Ishmael Reed” was, characterized the plot of The Haunting as Miranda being “visited by ghosts of people from history telling him how wrong he is,” to raucous laughter from the audience. Sagal was incredulous that anyone could dislike “the most beloved musical of modern times,” with a panelist suggesting: “I wonder if his other play is, like, Puppies Suck.” Ghosts “telling Hamilton how wrong he is… that’s the play,” Sagal summarized. It’s disturbing that Reed, a giant in the world of arts and letters, who is making a serious and important critique, can be dismissed as a laughable crank by a white comedian on a show for purported liberals.

Reed had biting words for Sagal and that “NPR nerd show,” as he put it, in an email to me a few days ago. “I realized that not only are those kids at Covington ignorant of American history, but our highly educated [as well],” he wrote. “This is because good old boy historians like Ron Chernow view this history as a series of great god-like men and they have dominated the profession.”

But, as Reed writes, “a rising group of historians, women, blacks, Latinos, and Native American historians are giving our history a different reading.” The Haunting may amplify their work.

If you appreciate our work, please consider making a donation, purchasing a subscription, or supporting our podcast on Patreon. Current Affairs is not for profit and carries no outside advertising. We are an independent media institution funded entirely by subscribers and small donors, and we depend on you in order to continue to produce high-quality work.