The morning of our trip to Nuevo Laredo, I am looking decidedly worse for wear. Numerous times the previous night, I awoke suddenly and compulsively googled “nuevo laredo” yet again on my phone. I must have been hoping, I suppose, that one of those times, I would get a result that says something like Nuevo Laredo Very Nice This Time Of Year. Instead, I kept getting stuff like Is it safe to travel to Nuevo Laredo? and Nine bloody bodies dumped outside Nuevo Laredo home with note: “This is not a game.”

THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE HAS ASSESSED NUEVO LAREDO AS BEING A CRITICAL-THREAT LOCATION FOR CRIME DIRECTED AT OR AFFECTING OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT INTERESTS, says the U.S. Department of State website, in ominous capitals. Do not travel due to crime. Violent crime, such as murder, armed robbery, carjacking, kidnapping, extortion, and sexual assault, is common. Gang activity, including gun battles, is widespread. Local law enforcement has limited capability to respond to violence.

“Guys,” I venture cautiously to my roommates, who are edging sleepily around one another in the tiny kitchen of our trailer. “I’m, uh, kind of fucking terrified about today.”

“I’m not!” announces S. cheerily. “I’m not scared at all. I trust A.”

Our friend A. is Mexican, and has been to Nuevo Laredo before. She is enthusiastic and indefatigable, with a self-deprecating sense of humor and a fund of funny stories, like the one about the time she accidentally fell asleep curled up behind the piano as a child and her family thought she had been kidnapped, or the time her graduation party was ruined because a drug lord showed up at the restaurant and filled the place with gunmen. Yes, of course I trust A. I would trust her to water my plants, to borrow my credit card, to drive me to the airport. But A. is, importantly, a 23-year-old girl, and probably no more use in a firefight or carjacking scenario than I would be. Moreover, between the fact that A. grew up in Ciudad Juarez—which was, until quite recently, the murder capital of Mexico—and the fact that A. is currently living in an old ranch house where she regularly finds live scorpions in her pajamas, I am not convinced that we assess risk in quite the same way.

My roommates, S. and L., are determined to go to Nuevo Laredo. They are undergrads who have taken their summer to come to Dilley, a tiny town in Texas, to help asylum-seekers in detention. There is a migrant shelter just across the Mexican border in Nuevo Laredo where recent deportees are often dumped, and S. and L. want to go see it. S. and L. are much more engaged with the real world than I ever was in college. They cry about their clients and work themselves to the point of emotional collapse. I love them so much it makes my lungs hurt. Because of them, peculiarly, this has been one of the best summers of my life.

If I plead out of going to Nuevo Laredo, S. and L. will think I’m a coward, which is clearly not an option, so my brain quickly reverse-engineers a list of reasons why going to Nuevo Laredo makes perfect sense.

- Even in a city with a high crime rate, it is statistically unlikely, on a single given day, that you will be murdered, especially as an outsider uninvolved in local disputes.

- If S. and L. and A. go to Nuevo Laredo without you and die, you’ll have to live with that for the rest of your life! Is that what you want for yourself?

- People die on this stupid planet all the time, many of them under deeply distressing circumstances! What, do you think you’re better than them?? You worm! You make me SICK!

Half an hour later, A. picks us up in her car; she is the designated driver for our trip to the border. She wants to follow up with a Cuban migrant she met at the shelter there last time, who got stranded in Mexico when the U.S. abruptly changed its “wet foot, dry foot” policy, which had previously allowed people fleeing Communist Oppression in Cuba to bypass the usual asylum process and get permanent residency in the U.S. There’s a chance he will want to approach a port of entry to ask for asylum today, and it’s sometimes useful to have a U.S. citizen on hand to help escort the asylees and document any bullshit that may go down at the bridge. We are also going to look around for a Mexican client of ours who recently lost her case and was deported; since Nuevo Laredo is the nearest border city to Dilley, it seems likely she would have been dropped off there, and possibly taken refuge in the shelter we are visiting.

Driving around Nuevo Laredo ourselves, however, is a dodgy prospect, so we are going to park the car on the U.S. side of the border and then get a ride. A. says she knows a taxi driver who can take us. Alternatively, the priest who runs the migrant shelter has offered to come pick us up. I opt vehemently for the priest.

“I feel like he wouldn’t cut and run if we get into trouble,” I say, even though I don’t know this priest from Adam. (A vague religious reflex also makes me think I will feel better about dying if there is a priest nearby, but I don’t say that part, because it is too loony.)

I think my nervousness is starting to rub off on L. S. is unperturbed. She is excited to go to Nuevo Laredo. She recently bought a fancy new camera and has just about exhausted all the photographic subjects available in Dilley. She’s going to take tons of pictures in Mexico, she says.

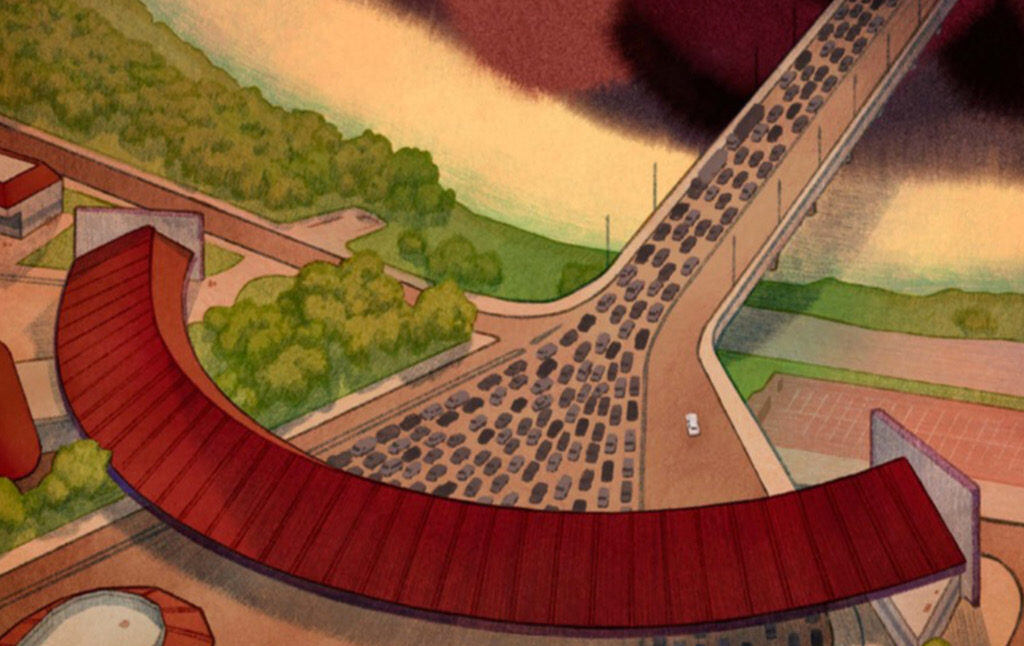

This is my first time crossing the southern border. I had somehow pictured that there would be a vast difference between the cities on the U.S. side of the border and the cities on the Mexican side; but aesthetically, at least, there isn’t. After parking the car on the U.S. side, we walk towards the port of entry; we hear only Spanish in the streets and see only Spanish on shopfront signs. We bump up against the river, and then we cross the bridge on foot. It’s simply a matter of flashing our passports and trundling through a couple of turnstiles. On the opposite side of the bridge, a long, long line of people are slowly shifting from foot to foot, waiting to be cleared to enter the U.S. from Mexico.

We cross the bridge, and now, suddenly, we are in Mexico. The priest isn’t due for a little while yet, so A. suggests we go over to a nearby shop and buy some agua fresca. IS THAT SAFE??? my brain screams. What if we buy from the WRONG SHOP? I know I am definitely being some brand of American idiot, but I am not sure which. Am I the kind of hysterical American who’s convinced they’re going to be knifed to death the minute they enter a less wealthy country? Or am I the kind of dumbfuck oblivious American who wanders unprepared into a clearly dangerous area and causes no end of hassle for the people who then have to clean up their damn mess? It’s hard to say.

At the moment, thankfully, it appears that the only dangerous characters threatening the shop are bees, who are buzzing drunkenly around the vats of sweet water.

We take our drinks to a pretty little park with a gazebo. The sun is shining, and people are going about their business without any obvious signs of terror. It feels like a normal summer day. A ragged old man in a wheelchair is propelling himself slowly around the park by pushing his bandaged feet against the ground. Someone stops to give him a bottle of water, and I watch as he pours the water out on a nearby patch of concrete to cool it, before shifting himself out of the wheelchair to sit on the ground.

“This is nice,” L. proclaims. “I don’t feel unsafe here.”

A man hawking newspapers passes by us and thrusts the daily edition under our noses. I get a fleeting glimpse of a jumbled mass of mutilated corpses before he moves on. Then a police vehicle comes around the corner. It’s a pickup truck and the bed of the truck is fenced in with a high railing. Standing in the bed, holding the rails, is a policeman in a black ski mask, bristling with weaponry, looking like some kind of mythical death-charioteer.

“Holy shit!” S. shouts, and darts forward to take a picture. I am about to panic when A. intercepts her. Better not do that, she says, the police don’t like being photographed. “They might take your camera away,” she says. (“OR THEY MIGHT FUCKING SHOOT YOU,” I think.)

The priest is late now. I have already written him off as murdered. Then A. gets a call telling us to meet him in the front yard of a nearby church. We find him wrangling with someone about the installation of a Jesus statue. The priest is Italian and very tall, and is wearing the kind of flat wool driving cap I often wear when it isn’t blistering hot out. He addresses us in Spanish at first, and then, apparently finding my accent too painful to listen to, reverts to English.

He drives us the short distance to the shelter in his van. The shelter has a metal security gate. There are some men lingering out front. “Coyotes,” the priest tells us, who have come looking for clients, desperate shelter guests who are ready to attempt a border crossing for the first or second or 15th time.

Inside, the shelter is a roomy building with tiled floors and little furniture. It has a listless, empty feeling: There are some migrants sitting on the floor or on plastic chairs, watching a movie on a projector; others are at tables playing cards. Many others are sitting doing nothing at all. The priest steers us to the laundry room, where we are assigned to sort through freshly-dried bedsheets and clothing for the new arrivals, under the direction of a smiling Honduran teenager who ribs us gently for our bad folding technique. I fall into conversation with a shelter guest who speaks fluent English with an American accent; he is bald and tattooed, but wearing round glasses that give his face an avuncular look. He had lived in the U.S. since age 16 and worked as a plumber before being apprehended for a drug offense and deported. He tells me he expects the U.S. to start feeling the negative economic consequences of its ever-hardening immigration policies. “Everything is going to fall apart. You know who does all the hard work in the U.S.?” he says. “Hispanics. Who’s going to do all that work if the Hispanics are all gone? You think black people want to do that work?” He scoffs. “White people?”

(In my mind I am transported, momentarily, from the sweltering hot laundry room to a freezing cold February day a year and a half earlier, when I fell into conversation with a homeless man outside the subway station in Harvard Square. He told me that he liked Bernie Sanders and might vote for him if he were nominated. But he also liked Donald Trump, he said, because he had lost his construction job and thought an illegal immigrant had taken it. It is strange that these two people’s suffering is separated by so much physical distance but so little substance, so frustrating that their grievances are directed at each other rather than the rich assholes who make them work for nothing.)

A little while later, the priest taps me on the shoulder. More people have just been dropped off at the border. He is going to pick them up and wonders if I want to come. More driving around murder town, NO thank you. But I say yes, because I don’t want this priest to think I’m a loser, especially since I am maybe counting on him to give me Holy Unction if I am mortally wounded at any point today. L. and I load ourselves into the front bench of a white serial killer van. Sweat is pooling in every indented surface of my body. It is 10,000 degrees and I am wearing a button-down shirt and trousers, because I had a vaguely thought-through idea that I would be safer in Nuevo Laredo if I dressed business casual. As we drive through the city, we address questions to the priest in Spanish and he responds, pityingly, in English. He tells us he has not been manning the shelter very long. They cycle through priests quickly at this post, because they are always getting death threats from the cartel. He has received many himself.

We stop at a building near the bridge where the girls and I first entered. The priest hops out and throws open the van doors. About 10 men pile in. I greet them awkwardly. One man seems about to get in, but then waves, a dismissive kind of gesture, and moves off back towards the building he came from.

The drive back to the shelter is mostly silent. After the passengers unload in the little front courtyard, they go through a brief processing. They give a phone number for a contact person, and then their phones are confiscated. Then, as if it were a TSA screening, they are asked to take off their shoes.

When they have all been admitted the priest tells me: “We must do all this because we sometimes have wolves in sheep’s clothing.” Then he explains that he is anxious because one of the men we have picked up is on the run from the Zetas. The cartel, and other criminal enterprises in the area, often target recent deportees to do tasks for them: Deportees tend to be desperate, without any support network or future prospects, sometimes without even a good grasp of Spanish, and there are few opportunities for legal employment. This man had done a few drug runs and then tried to flee. The Zetas had caught him and tortured him with a nail gun. The man says he managed to escape while his captors were sleeping. Now he has come to the shelter to hide.

The priest is worried that the Zetas may come here to look for him. A cartel operative could enter disguised as an ordinary migrant. The priest calls us briefly into his office and pulls an object out of his desk to show us. It is a knife with a curved, hooklike blade. “I found this under someone’s mattress the other day,” he says, conversationally. “I know what this is for!”

We walk back through the shelter building, looking for where A. and S. have got to. (“Even in a city with a high crime rate, it is statistically unlikely, on a single given day, that you will be murdered,” I tell myself. “Even if you are harboring a fugitive from a drug cartel, it is statistically—well, I mean, it would be a weird way to die, right? It probably won’t happen.”) Now the priest has put the thought in my mind that any of these people could be assassins, and they are all just walking around. I find the two other girls sorting through a garbage bag of newly-donated clothes. “THE ZETAS ARE COMING TO KILL US ALL,” is what I don’t scream, although I want to.

A. sees me and introduces me to her Cuban friend, who is trying to decide whether to ask for asylum at the border. I am a law student and so she thinks I may be able to tell him something about what’s in store for him. The man and I converse in a mixture of English and Spanish. I explain that it’s impossible to know for certain, but as a young, single man, there’s a very good chance he will be detained at the border. “For how long?” he wants to know. He is hesitant to cross at a port of entry if it means an indefinite spell in detention. You might get out on bond, I tell him, but there’s no guarantee. If he has a U.S. citizen relative and passes a credible fear interview, showing that he might have a good asylum claim, the chances of getting bond are a bit better, but the government does not really have to provide any justification for refusing to let immigrants out of detention. He might be there for months.

“Don’t cross until you have a lawyer on the other side,” I tell him. “Talk to your friends and family in the U.S. and have them help you hire one. You need someone ready to do your bond case if they detain you. If you wait until you’re in detention, it will be much, much harder to contact someone.”

Now what? There is nothing useful left for us to do. We have folded everything foldable on the premises. Our missing woman, the recent deportee from Dilley, is not here. Nobody here is lawyered up and ready to go request asylum at the border. We can’t leave the shelter and wander around outside, however, because it is not safe; none of the migrants here are allowed to leave the facility after they’re admitted, for their own safety, and to reduce the risk that people involved in criminal activities outside will try to hole up in the shelter. What to do? I could just make small talk, I suppose, with—with this giant roomful of men (assassins assassins they could all be ASSASSINS). Do they want to be pestered with my clumsy Spanish, anyhow? I am beginning to be overheated, and am now realizing that I am extremely hungry: It is mid-afternoon and I have not eaten since breakfast. There is some rumor that we might be able to hitch a ride back to the bridge in about an hour, but until then we must bide our time.

A. gets in some kind of dispute with the woman who runs the shelter kitchen. S. goes to stand in the walk-in freezer, where it is moderately cool. L. and I find a cool patch of tile to sit on. “I wish there were more women here,” she says. I have been thinking the same thing. Apparently there are women and children at the shelter from time to time, but it’s comparatively rare. At the detention center in Dilley, it feels effortless to establish rapport with the women. Men are harder. I wish, not for the first time, that there were some kind of button I could press to change my gender at will. The Honduran teenager who was helping us fold laundry sits down to join us just as L. and I begin discussing, in bad Spanish, how hungry we are right now.

“I was once hungry for three days and three nights,” the kid volunteers.

Well, now I feel like a fucking tool.

“When was that?” I ask.

“On the train,” he says.

“There was no food on the train?” L. asks.

“No,” he says. “I wasn’t in the train. I was on top of the train.”

We realize that he is one of the many migrants who have hitched a ride north on the freighter train known as “La Bestia.” Migrants leap onto the train as it begins to move and cling to the roof and sides. It is incredibly dangerous: Those who fall—or are pushed—from these trains sustain hideously gruesome injuries. The kid tells us that he is waiting for the right moment to cross the border: but not through a port of entry, so our escort would be of no use to him. This, too, is dangerous. Apart from the horrors of the immigration detention machine if he is caught, the cartels do not like people crossing the border around here without their say-so. If he tries to cross solo, or recruits the wrong coyote, things could get very ugly. The priest told us earlier that a man who had stayed at the shelter had tried to cross into the U.S. without cartel authorization. The cartel had caught him, killed him, and left his body outside the shelter as a warning to others.

As if on cue, the priest shows his face again: he is ready to drive us back. We all load back up into the serial killer van. The Honduran teenager offers to ride back with us and say goodbye. As we drive along, S. pulls out her camera and begins snapping pictures out the window. Whenever the car stops in traffic, she beams out the window at passersby, waving and shouting, “Hola!” The Honduran teenager turns to A. and whispers something urgently to her. A. puts her hand down over S.’s camera. “He says to put it away,” she says. “This is the territory of the Zetas, they do not like it.”

The van drops us off at the bridge. We wave goodbye and join the much longer queue on this side of the bridge to reenter the U.S. I glance casually over my shoulder and spot an armored green vehicle which a number of men in fatigues and riot gear, carrying machine guns, are hastily jumping into. The military vehicle screeches off suddenly into the city. What the fuck was that!! Nope, nope, I don’t want to know—I am leaving. I have been anxious for so long today that it feels like my inner organs are dissolving in acid. My muscles ache like I have done a brutal workout. All I want is to go home and take a long, environmentally irresponsible shower and then eat a can of beans while I watch Star Trek.

Back in the U.S., loaded up into A.’s car, we speed back into the interior of Texas. I contemplate my own cowardice. Investigative journalism is clearly not for me, nor am I any good at helping people when I am scared. I am now thinking of that roomful of hopeless men, drowsy in the heat, waiting for nothing. I wish I had talked to more of them, wish I had been less cautious and more friendly. The priest knew that some of them were probably murderers, and he did not let that stop him from making himself useful.

“Guys!” S. shrieks suddenly. “I feel like that was really dangerous!”

“Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaargh!” L. groans. “How are you only realizing this now?”

We hear the sudden yip of a siren behind us.

“Oh shit!” says A. “I always forget the—the—I forget the word in English—odometro—”

“The odometer—”

“Yeah, it’s in kilometros, so we’re speeding—a lot—”

We pull over. The officer approaches our window. I am relieved to see that he is not wearing a ski mask. A. is trying to explain that she is an American citizen, despite the car’s Mexican plates. He seems suspicious, seems not to catch A.’s explanation that her permanent address is in New Mexico. Oh god, he thinks we were on a drug run in Mexico, will he want to search the damn car—

“Where were you today?”

“Mexico, Nuevo Laredo.”

“You visiting someone there?”

“No—just, uh—just a tourist kind of visit—”

S. suddenly reaches into her wallet.

“Officer,” she says, charmingly. “I just want to say we’re so sorry, we weren’t paying attention to the speed, and I just want to let you know, my dad is on the force as well, and we’re sorry to have given you any trouble.”

Reaching across A., she hands him some kind of mysterious Police ID Card that all relatives of police officers apparently have. The police officer looks at it, then peers in at us, trying to work us out, four girls who look like they could be anywhere from 15 to 30 years old, speeding away from the border in a car with Mexican plates.

“Where are you headed?”

“Dilley,” we pipe up. “The detention center.”

“Oh!” he says, looking pleasantly surprised. “Y’all work at the detention center?”

“Yeeee-eesssssss,” we say, nodding vigorously, which is technically not a lie, because we do work at the detention center, just not for the detention center.

“And you’re going there right now?”

We all nod again.

“All right,” he says, handing the police card back into the car. “I’ll let you go with a warning. Pay attention to your speed.”

We drive off cautious, chastened. The officer follows behind us all the way to the Dilley exit. We can feel his eyes on our back.