A Nifty Little Trick for Facilitating Class Discussions

A way of running non-intimidating, inclusive seminars…

I’ve only ever “taught” two classes, and even then it was only as a graduate TA, handling the weekly discussion section while a real professor gave the lectures. But in both of them I tried a neat little discussion-facilitation technique, and it worked well, and I wanted to tell you what it is, how it works, and why I think it’s useful.

First, if you’re trying to lead a good discussion, whether in a small or large group, there are some inherent problems. As the teacher, you choose who to call on, and generally you want to make sure that everyone who wants to say something gets a chance, and one or two people don’t dominate the discussion. Unfortunately, some people naturally tend to put themselves forward more. They raise their hands at every question, and are always eager to speak. These participants can be both exasperating and a relief; exasperating because they tend to overwhelm everybody else, and a relief because you know that you’ll always have someone willing to respond to the question, and it won’t be a room full of crickets.

The teacher or discussion-leader wants to achieve a balance, so they don’t want to always call on the same people. But the more shy and reticent people often don’t even raise their hands. In many seminars in college, I was like this. It wasn’t that I didn’t have things to say, but I felt awkward putting myself forward. It seemed almost arrogant, presuming that everyone should listen to me because the thing I had to say was so insightful and intelligent that I should take up time the professor could be using to explain the real answer. I sat through many seminar discussions in which the teacher had a hard time getting people to talk, but never called on those who would definitely have had interesting things to say, simply because those people never volunteered. As you might expect, this often has racial and gender implications: Because white men tend to be more self-confident, they often end up speaking a disproportionate amount. It means that contributions are not actually apportioned according to a person’s desire to contribute, but their willingness to ask to talk, which is different.

There is a simple way of solving this: cold-calling. Don’t call on students who raise their hands, call on whichever students haven’t spoken in a while. Achieve a diversity of participants by force. But this simple way is also a terrible way. Cold-calling is the preferred technique of the old-fashioned law school professor, the one who humiliated students by calling them and making them admit that they didn’t know the answer or hadn’t done the reading. I hated cold-calling in law school, because it meant that you could never daydream for a moment, since at any second your classmates could turn their heads towards you and watch you stammer trying to remember what you’d just been asked. There are ways to soften cold-calling, like designating parts of the class to be “on call” in any given session. But students should be able to opt out, because sometimes you’re just not prepared.

Yet there’s something I do like about cold-calling, because there are some students (like college me) that kind of want to say things but don’t know how to, or don’t want to, push ourselves into the discussion. Those students feel like they ought to have something really intelligent prepared to say before they interrupt, and it’s kind of nice to have the professor tell you that they want to hear from you, asking you what you think rather than just waiting until you’re confident enough to burst in with what you think.

So when I started teaching, I tried to come up with a system that would have the positive features of voluntary participation (the people who don’t want to speak don’t have to speak) without the negative ones (the eager beavers dominate), and the positive features of cold-calling (bringing in reticent people, diversity of participants) without the negative ones (pants-shitting terror when the professor calls your name). The solution I devised was the color-coded card system. (I adapted it from a technique a law professor of mine, James Forman, used to use. His did not involve colors.)

Each student gets a piece of card, which is printed in three sections, with indentations on the borders of each section to make for easy folding. The sections are red, green, and yellow. There is a little white tab on one end, so that it can be folded and stuck together with a piece of double-sided tape. Students write their names on each of the sections, as follows:

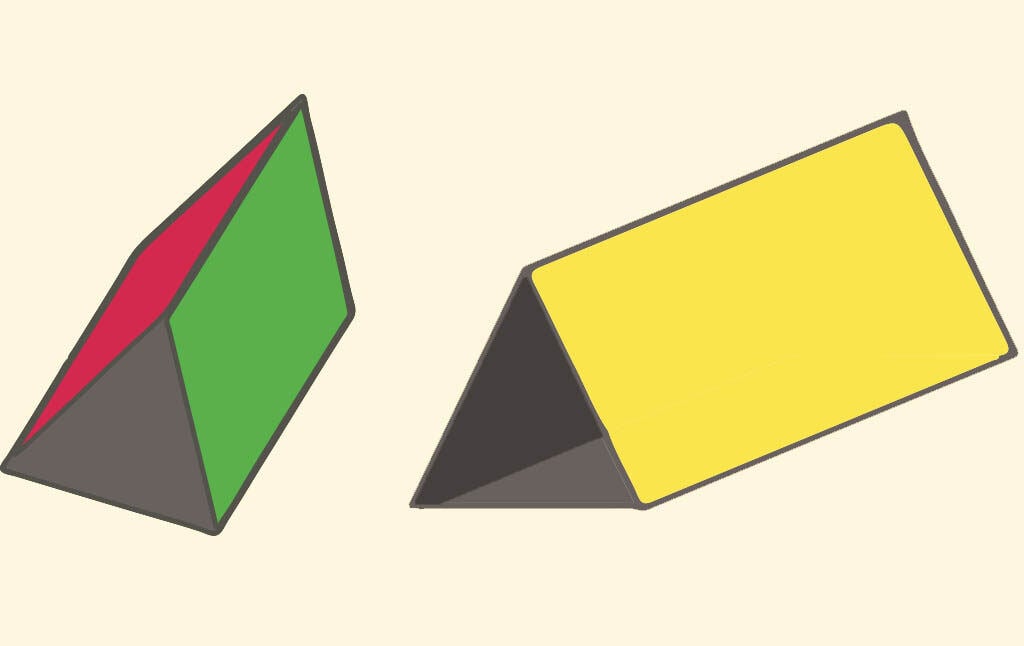

Then, the cards are assembled into a prism, like so:

Decorate and customize as desired!

Each student places their name card in front of them, and positions it so that one side faces the discussion leader. They are told that they should rotate the card so that the color the discussion leader sees is either red, green, or yellow. The meanings of the colors are:

RED – I do not wish to be called on.

YELLOW – I do not mind being called on.

GREEN – I would like to be called on.

Green is therefore the equivalent of raising your hand. Yellow is the equivalent of being open to cold-calling. And red means opting out of cold-calling. The students are asked to default to yellow, but are told that they should not hesitate to go red if they do not wish to speak. (The discussion-leader should have their own namecard, and should turn it to red and keep it there for a while so that students know this is acceptable.) At the end of each session, the instructor collects the cards in a box and hands them out at the end of the next class.

Here are the instructions I gave to students on the first day:

When I tried this system, I found that it worked very well, and was also fun. It had several advantages: First, it allows the discussion-leader to cold-call, but doesn’t make it intimidating, because students can go red at any moment that they wish to opt out or do not know an answer. Second, it allows students who have things they particularly want to say to “raise their hands” by going green, but the discussion-leader can simply ignore people who continuously go green and can choose to pick a few people on yellow instead. Third, it makes participation and non-participation almost effortless. Nobody needs to sit waving their hand in the air, and the discussion-leader doesn’t need to try to remember who had their hand up recently. They can look out over the room and see immediately who is volunteering, who is declining, and who is open to being brought into the discussion at the teacher’s discretion.

A few notes: It took a couple of session to get used to the system, but once my students had got the hang of it, they really liked it. Nearly everyone in our seminar participated in every single discussion, while my fellow TAs struggled to get their classes to speak. Having the freedom to cold-call is very useful, because it means you can bring people in, but they won’t feel intimidated if they know they don’t have to do it. I had some students who were very shy, and remained on red for most of a session, but I would notice them turn their card to yellow every once in a while, before turning it back to red. For them, yellow was the equivalent of green, and it provided an easy way for me to notice when they had something they wanted to say but didn’t want to put themselves forward.

Still, the system only works when the instructor is committed to using it well. The instructor needs to watch the group carefully for card changes. They also need to make people comfortable being on yellow by not making it intimidating to get picked. Otherwise, students will just switch between red and green. Ideally, you need to have a group of mostly yellows, with a few reds and a few greens. If you’re not getting that balance, you should encourage reticent students to try spending some time on yellow.

My peculiar little system might not work for everybody. But it did what I wanted it to do: It allowed me to call on people other than those who raised their hands, without creating an intimidating environment. (As a side-advantage, it also means that neither the instructor nor the students will ever forget anyone’s name, because they’ll always have it in front of them.) It’s not a substitute for careful, conscientious, inclusive discussion-leading, but it can complement it.

This, then, is my small contribution to pedagogy: Robinson’s Patented Color-Coded Compassionate Cold-Calling Card System. It’s a bit odd, I realize, but if nothing else I hope it can help us identify some of the problems that occur with discussions and methods we might devise to fix them.

Here is the PDF I took to the print shop to have the cards printed. Make sure to ask for indentations on the borders between the colors so the cards can be folded easily.

If you appreciate our work, please consider making a donation, purchasing a subscription, or supporting our podcast on Patreon. Current Affairs is not for profit and carries no outside advertising. We are an independent media institution funded entirely by subscribers and small donors, and we depend on you in order to continue to produce high-quality work.