The Paradox of the “Problematic”

How do we deal with morally tainted cultural products? C.L.R. James took a simple approach…

The trouble with trying to enjoy anything is that almost everything is tainted somehow. Many of the products we consume are produced under indefensible labor conditions, or involve terrible animal suffering. Yesterday I went to an idyllic local park and cycled around the fountains. It was a lovely afternoon, and I thought to myself “Well, if this isn’t perfect, I don’t know what is.” Then I looked around and realized everyone in the park was white, in a majority-black city, and I remembered that I was in a highly segregated area of town, and that this little slice of paradise existed in part because of great wealth inequality.

With cultural products especially, we frequently face the discomforting question: how do I reconcile my love of this thing with my knowledge that the person who created it was a complete bastard? The most prominent contemporary instance of this dilemma is the work of male film directors/writers/comedians who have committed sexual misconduct. This question may be easily answered in certain cases, such as that of Woody Allen, where the person’s body of work is of poor quality and will not be missed. It’s harder when we really don’t want to have to live without some film or song or book.

This is the Michael Jackson Problem: it would be very uncomfortable to listen to music by someone we knew to be a sexually predatory pedophile. But Michael Jackson’s music is utterly beloved and does not have any real objectionable content (uh, except for that one song with the anti-Semitism in it). What do we do? The worst possible response, obviously, is to allow our love of the work to influence our judgment as to whether the factual allegations are true; Thriller is an incredible album, therefore I’m going to just treat Jackson as an endearing but bizarre man-child and avoid confronting the evidence. But approaches that discard perfectly good music in order to make us feel better don’t actually seem to help anyone, either.

Fortunately, thanks to the #MeToo movement, it is less and less the case that a stellar body of artistic work will excuse or mitigate misconduct in the public’s perception. But it’s still unclear what we actually do with that work. Can we keep enjoying it? It doesn’t do any harm, right? Maybe if we just listened/watched/read while feeling really bad about it, we would still be good people. Things obviously become murkier when the works in question are deeply personal, such as Louis C.K.’s “honest” feminist-friendly standup routines, or Nate Parker’s Birth of a Nation film. Parker’s film contained a fictionalized rape scene, which served as the impetus for Nat Turner’s revolt, and Parker himself had been accused of rape. The more personal the work, or the more relevant the work is to the misdeed of the creator, the more difficult it is to sort anything out.

Contemporary examples aren’t even the most difficult, though. The real problems come with enjoying material from the much more explicitly oppressive and bigoted past: film noir with gratuitous scenes of abuse, Huckleberry Finn, Oliver Twist, the Agatha Christie novel with the incredibly racist original title. I love the Beatles, and knowing that John Lennon hit his wife did not change that fact. But it did make me feel queasy when I considered what the catchy song “Run For Your Life” was about. (“You’d better run for your life if you can, little girl / Catch you with another man, that’s the end, little girl”) And when I thought how casually abuse was portrayed in some 60s pop songs (“Johnny Get Angry,” “Treat ‘Em Tough,” “He Hit Me (And It Felt Like A Kiss)“, it became hard not to wonder what silent suffering was going on beneath the fun and sunshine.

This is not just politically correct culture-policing; I find the words of the Declaration of Independence strange when I think about the fact that the man who wrote them raped an underage slave. Several generations of philosophers have now had to grapple with the “Heidegger was a Nazi” problem, and it’s not a trivial one: if we think a person’s mind was great and powerful, we at least have to explain how that great and powerful mind could both produce great insight and endorse horrific conclusions. But so many “great and powerful minds” have endorsed some kind of horrible conclusion sooner or later. Dickens celebrates the downtrodden in a miserably unfair society and then endorses imperial slaughter. Germaine Greer writes brilliantly in favor of women’s liberation and then says horrible things about transgender people. Even Frederick Douglass, who was the first person I could think of as an example of a great historical figure who didn’t have some moral stain, was a feminist well before it was popular and yet apparently treated his own wife neglectfully. In some cases, we can just say that “nobody’s perfect.” In other cases, the consequences are so serious that it’s hard to see how a person can be redeemed: Lyndon Johnson’s antipoverty programs can’t make up for the fact that he pursued a racist war that left 1,000,000 Vietnamese people dead, anymore than Stalin’s industrialization of Russia can compensate for the Great Purge.

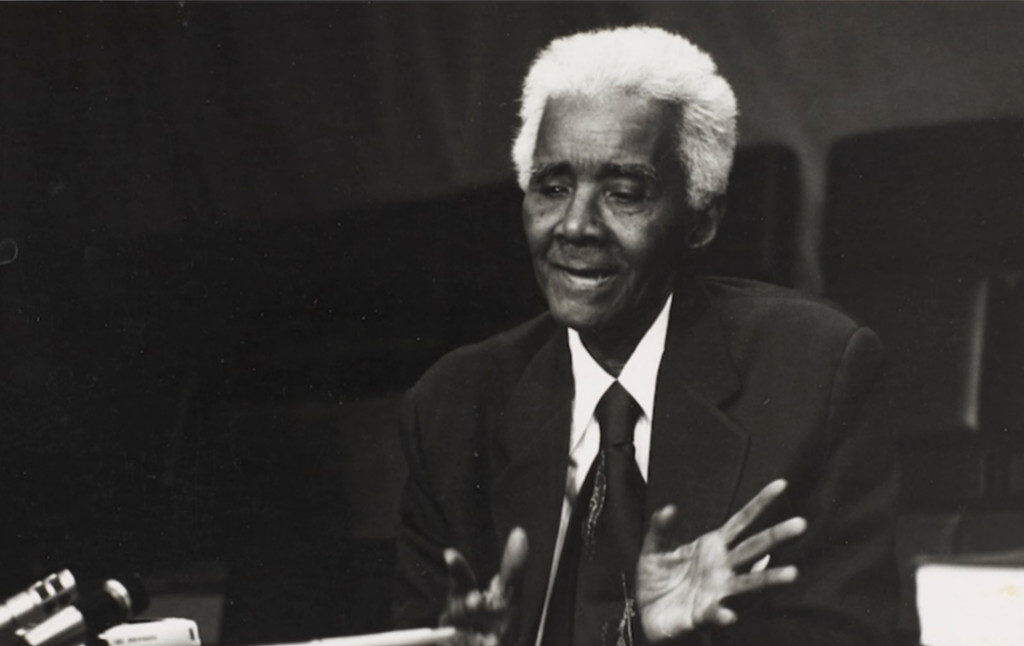

This debate comes up a lot around “The Enlightenment” and “Western culture.” Should the West’s history of genocide and colonialism lead us to deride “Enlightenment thought” as little more than rationalizations for prejudice? Or are we throwing the baby out with the bathwater? Kenan Malik, in his truly excellent The Quest for a Moral Compass, which tracks the historical efforts of peoples around the world to develop notions of the good, provides a useful way of thinking about this question in a brief discussion of Toussaint L’Ouverture and C.L.R. James. L’Ouverture, Malik says, faced this problem acutely: he was enslaved by France, and yet inspired by the French revolutionary ideals of “Liberté, égalité, fraternité.” But a subtle mind is able to hold multiple ideas at once, and the Haitian Revolution could take inspiration from French rhetoric about human equality without endorsing the French perversion of that ideal, just as Martin Luther King could later invoke the principles of the American Founding while rejecting the acts and hypocrisies of the American founders. Malik also profiles the fascinating figure C.L.R. James, whose The Black Jacobins is about the Haitian fight for independence. James was a staunchly anti-colonialist Afro-Trinidadian, and yet he was deeply grounded in Western thought and literature, and was inspired just as much by Shakespeare as by the culture of his “own” people. James explained that it was simple for him to take and appreciate what was good about the West while deploring what was inhuman:

We live in one world and we have to find out what is taking place in the world. And I, a man of the Caribbean, have found that it is in the study of Western literature, Western philosophy, and Western history that I have found out the things that I have found, even about the underdeveloped countries… I denounce European colonialism but I respect the learning and profound discoveries of Western civilization.

Malik says that James found a way for colonized peoples to “break out of the particularities of their experiences and [enter] a more universal form of discourse.” He could love cricket without reservation, while having a better understanding than most British people of the grim historical reasons for his encounter with the sport. In using the Western canon as a set of sources for the development of his anti-colonial politics, James showed how one could liberate one’s self politically from European conquest without hurting one’s self intellectually by declining to consume the fruits of European culture. This cosmopolitan, universalist approach allowed James to produce an exceptional body of radical scholarship, which used the intellectual tools of the Enlightenment as powerful weapons against its own most oppressive tendencies. (Malik also points out that even Frantz Fanon, despite a “seeming disdain for European culture,” turned to European thought to find solutions to the problems created by European peoples.)

There will never be correct answers to the “separation of art and artist” question, or the question of how to approach the cultural products of bleak and bigoted periods of history. There are good arguments to be made that it’s appalling to discuss the technical cinematic merits of Triumph of the Will, Gone With The Wind, or Birth of a Nation (the old one). But it’s necessary to avoid simply lumping every troubling product into that nebulous category “problematic.” “Problematic” as a label doesn’t appear to have any fixed meaning, and is a catch-all descriptor for very different offensive things ranging from the “inelegantly articulated” to the “horrifically bigoted.” It also offers a recipe for inaction, because it diagnoses problems without hinting at their specific nature or their potential solutions (the solution is for the thing to be less of a problem). Nearly everything is problematic in one way or another; the difficult question is not “Is this problematic?” but “Given that this is probably problematic, how can we approach it in a way that allows us to benefit from its achievements but acknowledge and deal with its problems?” I’m not sure what you do sometimes; I don’t really want to watch Nate Parker’s movie, but that’s more because I don’t like to watch rape and violence generally, rather than because he has been accused of rape. And each person’s approach will be different: it’s easier for me to enjoy the cheesy kazoo solo in “Johnny Get Angry” than it might be for someone more personally disturbed by a song that seems to imply women want to be verbally abused by their partners. But I do think the soundest general approach is James-ian: find what’s good and use it for your own ends, discard and vigorously criticize what’s bad. I will accept wisdom from any source, however tainted, because a messenger’s moral transgressions shouldn’t result in the rest of us being deprived of insight.

If you appreciate our work, please consider making a donation or purchasing a subscription. Current Affairs is not for profit and carries no outside advertising. We are an independent media institution funded entirely by subscribers and small donors, and we depend on you in order to continue to produce high-quality work.