Should We Talk To White Supremacists?

Is it even possible to have a productive conversation with a racist? We can’t say until we’ve tried…

Recently, I’ve been thinking about how to talk to white supremacists.

Conventional wisdom says that it can’t be done, at least not productively. For decades, Americans on both ends of the political spectrum have engaged in the project of shunting outright racism to the margins. As a result, we now consider racists to be monsters as foreign and grotesque as Godzilla. In fact, in the aftermath of the election, hundreds of thousands of keystrokes were devoted to answering the question of whether the left should deign to talk to any Trump voters, never mind avowed white supremacists. For many, the racist rhetoric that Trump rode to victory was so overt that anybody who voted for him lacked any “plausible deniability” of their bigotry.

These voters, it is assumed, cannot be persuaded. Although they are nearly demographically identical to the electorate that supported Romney, Bush, and McCain in past cycles, because Trump voters are real racists, the act of reaching out to them is a kind of political treason on the left, for whom explicit (but apparently not tacit) racism is a bridge too far. According to this logic, prejudice is as immutable a characteristic as skin color itself. And since racism is argued to be the single animating voting issue for this population, no appeals to other interests are worth making.

Not only is talking to Trump voters seen as futile, a desire to better understand them is often stigmatized as reflective of a preference for Trump voters and/or the bigoted ideologies that serve to marginalize communities of color, LGBTI persons, and religious minority groups. Bernie Sanders’ statement that Democrats should talk to Trump voters has been used to imply he’s racist. An A&E documentary about the Ku Klux Klan set to air in January was canceled in the wake of public backlash: audiences were convinced that the show would glamorize the KKK—a dangerous proposition in the age of Trump. In fact, the show was designed to do the opposite: it emphasized efforts to help extricate members of hate groups, including young children, from their environments. Regardless, the show was pulled from the schedule after it was revealed that its subjects were paid to participate—a tipping point that felt more like pretext than principle.

Moreover, among the political left, those who would talk to Trump voters to persuade them are recklessly conflated with those who would appease them through triangulation and compromise. People who empathize with these voters’ legitimate economic concerns are accused of caring more about Trump voters than about other groups perceived to be more deserving of empathy. Strategists who seek to better understand right-wing beliefs in order to undermine them are perceived to value them instead. No conversation with a Trump supporter (and certainly none with white nationalists) is acceptable unless it is openly antagonistic.

I’m not convinced this approach is helping.

As a practical matter, to write off a population as broad as “Trump voters” or even “white supremacists” is politically irresponsible. With respect to Trump voters, post election analysis has proven that an electorally significant percentage were once Obama supporters. This means that either racism isn’t as fixed as implied, or, in the alternative, that racists might be motivated by something other than hate at the ballot box. And although the idea of courting white supremacists is, of course, distasteful, doing so feels less controversial once you consider “white supremacy” to include a spectrum of beliefs from which few people are excluded. If everybody is racist, to refrain from talking to racists is to retreat from politics entirely.

Racists are said to wear white hoods, or perhaps now, white polo shirts. They can alternatively be identified by a swastika armband, or a Confederate license plate. Because neither Democrats nor Republicans are above wielding class as a weapon when convenient, we are also told that they lack teeth, thirst for Mountain Dew, and are, on the whole, “deplorables.” They are beneath political acknowledgment, beyond redemption.

But white supremacy is not limited to those who have made it a defining sartorial characteristic. The Republican Party may get the vast majority of the Klan vote these days, but the ideology of white supremacy is bipartisan. White supremacy is deeply ingrained in people of all political stripes, because it’s such an inextricable part of the American subconscious. It can be found in the presumption that urban black and Latino youths are uniquely lacking in empathy, making them “super-predators,” or that a black presidential candidate wouldn’t be “clean” or “articulate,” or that the achievement gap is due to innate, biological factors. The century-long failure to remove Confederate monuments from public plazas makes the American public writ large complicit in white supremacy. Pretending that white supremacists are typified by, for example, Charlottesville protesters, vastly understates the problem. (In fact, implicit bias tests show that even ethnic minorities harbor bias against other people of color. Tests that measure how quickly a person is able to associate white faces or black faces with various objects or words, or accurately identify men of various races who are holding guns rather than ones holding innocuous gun-sized objects, reveal that even the most valiant of social justice warriors show a “moderate automatic association between weapons and black faces,” as my own test revealed.)

Last summer, liberals breathlessly cited a Reuters poll showing that 40% of Trump supporters believed that blacks were more “lazy” than whites. Most ignored the findings showing that 25% of Clinton voters agreed. Either the 22.5% of Clinton voters who believe that blacks are “less intelligent” aren’t racist, or issues beyond white supremacy motivate these people’s votes. Speaking to these people is clearly a feature of doing politics, and a refusal to do so simply cedes these people to the other side, to disastrous consequence.

So if everyone’s a little bit white supremacist, public proclamations about who we will and won’t talk to seem, well, a little bit silly. But even if we only think pragmatically, it’s important to know thy enemy. The odds that a good chat can convince a racist to swap the KKK for BLM are slim, but those seeking to exert national political influence would do well to think about how to best communicate with all Americans.

So: how do we to talk to those who are, at best, indifferent to, and at worst, enthusiastic supporters of the white supremacy that characterizes Trump’s presidency and the country more broadly?

White supremacists appear to fall into two camps: they either don’t care that they’re racist, or, somewhat remarkably, they persist in believing that they are not racist in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary. One notable defender of the Charlottesville protest managed to unironically utter the phrase “Martin Luther Coon” in the middle of his case for why celebrating the Confederacy isn’t racist. Suffice it to say, in the face of such shamelessness, I am skeptical about how far guilt, the favored liberal method will take us. Often it just induces anger and threats. When members of an online group called “Upper East Side moms” were called “racist” for downplaying the importance of white supremacy, they did not immediately “check their privilege” and repent. Instead, they threatened legal action. If the Upper East Side moms can’t be shamed out of their racist beliefs, it’s unlikely to work on a man wielding a Tiki torch.

But I do think historical context is a powerful corrective. Research suggests that our perception of the Confederate insurrection is significantly influenced by what we were taught about it in school. Children who learned about “the war of northern aggression” or “the war between states” are less likely to view Confederate statues as monuments to slave-owners than those who learned about the “Civil War.” Students who were taught about the cruel and inhumane living conditions to which enslaved blacks were subjected are less likely to “cling to the romanticized versions of the happy slave life.”

Many Americans learned only recently (or are still unaware) that the majority of Confederate statues were not actually raised to commemorate dead soldiers, but were put up during Reconstruction and the civil rights era—periods during which black political and economic power grew—in an effort to instill fear in blacks and make tangible the always present specter of racial violence. Understanding that context, and realizing that the statues aren’t actually historic in any meaningful sense, makes it easier to conclude that they should come down. Working to give people a better understanding of American history, ancient history, science, immigration patterns, and the myriad ways non-Europeans have contributed (and birthed) civilization is guaranteed to be more effective than telling a man with a swastika tattoo he’s racist.

In the media interviews of members of the far right after Charlottesville, we could see many excellent examples of what not to do. Too often, journalists came to these discussions unprepared to handle their subjects effectively. Some recoiled with shock and were derailed by the open expression of bigotry that, presumably, made the chosen interviewee an attractive subject to begin with. Opportunities to challenge the subjects effectively were missed.

Recently, an interview with KKK leader Chris Barker by Afro-Latina journalist Ilia Calderón made headlines after he threatened to “burn” the reporter—along with 11 million undocumented immigrants—“out” of the country the same way that “we” (presumably meaning white supremacists) killed six million Jewish people in the Holocaust. The interviewee was a horrifying individual. But it’s worth thinking about how to deal with someone like this.

Barker opened with a version of the classic salvo: “Why don’t you go back to your own country if it’s so great?” Any journalist preparing to interview a Klansman, especially if that journalist is a Colombian immigrant who has covered immigration and anti-Latino sentiment in America, should be prepared for that kind of remark. But Calderón took the bait, responding: “I go back all the time.” Instead of challenging the premise of the question—which was that Barker (who apparently identifies more with WWII-era Germans than Americans) has an intrinsic right to this country that supersedes that of people of color—Calderón defended the value of Colombia. It’s a fine country, of course, but that’s not the point. Whether or not Calderón or any other immigrant likes or returns to their country of birth is immaterial to whether they should be extended various rights and freedoms in the United States. But Calderón, seemingly unprepared for a fairly standard dose of racist rhetoric, debates on the white supremacist’s terms rather than challenging his faulty presumption that Calderón’s value as a human being is somehow linked to how fond she is of Colombia.

When Barker later threatens: “I’ll chase you out of here,” Calderón parrots back mockingly: “Oh, you’ll chase me out of here?” Repeating your rhetorical opponent’s last words is never sign of a strong argument, and perhaps predictably, Barker escalates by calling Calderón a n*gger. Calderón replies she finds that offensive (as though offense wasn’t the purpose of the slur), and the interview, from the perspective of the viewer, ends.

I highlight this interview not to further antagonize Calderón or to blame her for Barker’s racism—she’s been through enough. What this interview shows is that the reason “talking to racists” and/or Trump supporters is perceived as futile is because, in the way it’s often attempted, it is. A well-equipped interviewer would come with nerves steeled and armed with facts about inventors and poets and architects of color whose very existence disproves the myth of white superiority. She would be a historian who could point to the independent origins of math and science and medical knowledge all around the globe—often centuries before those insights made it to Europe. She would be able to listen without reacting, and use compassion (whether sincere or not) to disarm and elucidate.

When the white supremacist’s wife chides him to “watch your mouth” after he calls Calderón a n*gger, she might have asked her why she stepped in on his behalf. My instinct is that this moment of civility was an opening to a conversation which might have forced Baker’s wife to recognize Calderón’s humanity. Is that guaranteed? Of course not. But I have yet to see evidence that it’s not worth trying: as far as I can see, it is rarely sincerely attempted, and when it is, it’s met with some success.

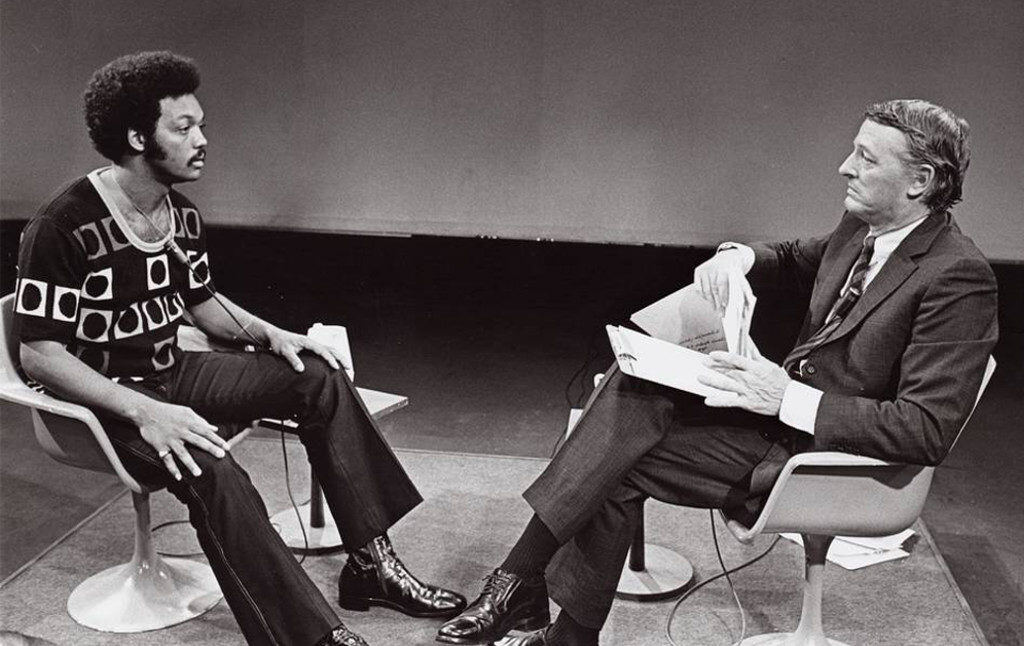

Take the example of Daryl Davis, an African American blues maestro made famous for convincing over a dozen members of the Klan to both literally and figuratively hang up their robes. This white whisperer has said that the most important lesson he took from his years of befriending and converting white supremacists “is that when you are actively learning about someone else you are passively teaching them about yourself.” An interviewer positioned to learn and listen, rather than react, might advance mutual understanding by teaching by example. Davis has over a dozen Klan robes in his closet, each of which represents a Klansman who has given up the KKK after befriending Davis. In the face of those results, I, for one, am eager to give persuasion a try.

It’s hard to discern from the short available clip of Calderón’s interview with Baker what her goals were, or if she had other questions that might have done more than sharpen our expectations of What A Racist Sounds Like. But after watching this and other similar encounters with white supremacists, I would have loved to have heard Calderón’s interviewee answer the following questions:

- When did your family immigrate to America? Should white Americans, the majority of whom immigrated to the United States well after Black Americans (not to mention Native Americans), also have to repatriate? Why not?

- How did you come to believe whites are superior? What did your parents tell you about race? Have you ever had a meal with a non-white person? (Wanna grab some Chinese food?)

- How do you reconcile your support of genocide with the teachings of your religious faith—a faith which you’ve referenced in this interview?

- What are the biggest political issues your family is struggling with? Unemployment? Lack of healthcare? Poverty? Which political party is most likely to address those issues? Do you accept public assistance? Are you on Obamacare?

- What is it about white people that makes you believe in your own superiority? What is it about others that makes you believe they are inferior?

I don’t mean to imply that speaking to white supremacists is an easy job. Last Thanksgiving, I interviewed a Trump voter for my podcast, and though I had prepared pages of notes, I, too, was drawn into the rhetorical weeds by my interviewee’s interjections about how Black Lives Matter is a terrorist organization, and why Obama is the “real racist.” But although I was at times derailed, the frolics and detours I entertained were ones from which I learned. I learned that the imprecise and exaggerated language liberals use at times to express offense often does more harm than good: Trump’s statements regarding Mexicans were bad enough without mis-attributing to him the sentence “all Mexicans are rapists,” as Tim Kaine did last August, a choice which made liberals vulnerable to accusations of “fake news.” I learned that the gap between how liberals and conservatives understand racism is largely rooted in an ignorance about history: for example, when I attempted to ground the justification for government assistance in the history of the government’s sponsorship of racism, my interview subject claimed to “not know much” about Brown v. Board or redlining. And as contentious and exasperating as that interview was, I learned the important lesson that it’s possible to inch slowly toward some mutual understanding. Centrist Democrats famously champion incrementalism. This would be a good time to put that patience to work.

Let me be clear about this: I can’t guarantee results, but I’m encouraged by the evidence. Barack Obama effectively used the rhetoric of racial understanding to bring the much-discussed “working class whites” to the polls in a way that Hillary failed to do. As part of his Unity Tour last March, Bernie Sanders visited McDowell County, West Virginia, a county that overwhelmingly voted for Trump, and managed to convince at least one rural white Trump voter that “every American citizen should have health care”—this despite the fact that the voter appeared to be as much a caricature of a “deplorable” as any that has ever lived in the Democratic imagination. Of course, there’s no indication that the coal miner Sanders persuaded is a neo-Nazi—nor was the acquaintance I interviewed on my podcast. But a certain brand of liberalism would still assume him too irredeemable to be fit for a progressive coalition, solely because he voted for Trump. That way of thinking has to end.

No one has to talk to an avowed white supremacist. Certainly no person of color should feel compelled to place themselves in the crosshairs of white supremacist hate speech. Having one’s intrinsic worth questioned so frankly is an assault on one’s personhood second perhaps only to violent assault. Even less overt forms of racism have measurable impacts on the mental and physical health of people of color. But systemically, the left must engage. It’s the only way to get rid of racism, and it’s the only way to win.

Read more of Briahna Joy Gray’s work in our print edition and our new paperback essay collection The Current Affairs Mindset.