Bad Ways To Criticize Trump

Progressives need to focus their critiques on issues that actually matter to people…

It is very easy to find ways to criticize Donald Trump. Because he has so many loathsome traits of character, Trump provides the prospective critic with ample possible lines of attack. It can be difficult to know where to start. Is it the bombast? The racism? The massive serial sexual assault? Is it the mob ties? The fraudulent university? The overstated wealth? How about all of the lies? Or the false promises? What about the near-total lack of an attention span, and the ignorance of global affairs? Should we dwell on his childish personality? On his bullying? His vulgarity? His sexism? Trump presents a veritable buffet of appalling qualities, and it is nearly impossible to decide where to start.

But not all criticisms of Trump have equal effective force. After all, surely it matters more that he has actually committed serious sex crimes than that he has possibly made some bizarre reference to Megyn Kelly’s menstrual cycle. Likewise, his history of making it hard for his contractors to feed their families is far more reprehensible than his outlandish tweeting habits or his risible haircut. Trump’s actions have hurt people in serious ways, and his behavior can be divided into that which is merely silly (such as his calling Rosie O’Donnell rude names) versus that which actively causes pain (such as his almost certainly having raped someone).

Unfortunately, media outrage about Trump frequently adopts a uniform level of outrage at his acts. Trump’s history is treated as a set of bad things, meaning that few distinctions are made among which kinds of transgressions are worse. But there are lesser and greater crimes. Trump’s constant theft of wages and payments from dishwashers, cabinet-makers, and servers is far more consequential than, say, his promotion of a failed mail-order steak franchise. But press coverage often treats such things as being of equal interest. For example, an Atlantic article compiling a definitive list of Trump’s “scandals” lists both the sexual assault allegations and the fact that Trump may have once bought concrete from a Mafia affiliate. But surely grabbing dozens of women’s genitals without their permission is worse than having purchased building supplies from someone vaguely shady. And ThinkProgress put as much effort into its comprehensive (half-joking, but carefully-reported) history of Trump Steaks as its coverage of the story of Trump’s alleged brutal rape of his wife.

Likewise, Mother Jones magazine ran a series on Trump called “The Trump Files.” It included plenty of damning information about Trump’s use of lawsuits and harassment to keep his critics quiet. And yet other entries in the series included: “Donald Thinks Exercising Might Kill You” and “Donald Filmed a Music Video. It Didn’t Go Well.” In the Trump files, one can find plenty of information about how Trump cheated the New York City government out of tax money, or dumped his business debts on others. Yet one can also find files on some of his more ludicrous reality TV show pilot ideas, and “the time a sleazy hot tub salesman tried to take Trump’s name.” There’s a funny file about how Trump couldn’t name a single one of his “hand-picked” professors for Trump University. But the important point about Trump University is not that Trump lied about knowing who the instructors were, it’s that it bilked people out of their savings.

Criticisms of Trump therefore need to be made carefully, because they can all end up bleeding together as noise. This is a good reason for, if not ignoring entirely, then at least giving very selective coverage to the rubbish Trump posts on Twitter. A Tweet is not, after all, the most consequential of communications. And while it may have been interesting for The New York Times to have two reporters compile a vast list of “the 289 People, Places, and Things Donald Trump Has Insulted on Twitter,” a journalist’s time may be better spent on more useful investigative work.

It’s understandable why Trump’s Twitter feed attracts so much attention. After all, it’s outrageous, and frequently very entertaining. How can anyone resist finding out what he has to say about Glenn Beck (“mental basketcase”), Ruth Bader Ginsburg (“her mind is shot!”) or Saturday Night Live (“unwatchable!”) The truth is, no matter how much we may deny it, on some level many of us enjoy watching Trump defy taboos and be nasty to people. After all, the entire reason for things like the New York Times Trump insult database is that it’s amusing. People hate Trump, but they also love hating him.

There’s also a convenient rationale for reading Trump’s tweets, especially now: it provides closer access to the thoughts of the President of the United States than anybody has ever previously had. For journalists, there is good reason to cover Trump’s social media outbursts: his words are now important. When the President speaks, it moves markets. It can create diplomatic incidents. Like it or not, Trump’s tweets do matter.

The problem, however, is that Trump knows this. He knows that every noise he makes is amplified by the press. And he knows that, as journalist Michael Tracey writes, “his tweets will be instantly picked up by all the typical news outlets [and] everyone will frantically seize upon every crass Trump tweet, and use it to set the “tone” of their coverage for the day.” Thus Trump’s rude and provocative tweets are calculated for maximum effect. And while members of the press may insist that they understand Trump is trying to get attention, they nevertheless end up granting him precisely the attention he seeks.

It’s a difficult paradox to get out of. You can’t ignore Trump’s tweets entirely, because it’s news if the President of the United States has publicly threatened or disparaged someone. But at the same time, by affording coverage to whatever Trump wants to say on Twitter, one allows him to set the agenda and make the news about himself.

Yet it’s possible that a balance can be struck. Tracey offers a series of tips to journalists for how to deal with Trump’s tweets, which balance the necessity of paying attention to the President with the reality that the current President is a manipulative attention-seeker. As he writes:

– You don’t need to share, comment, react to, or write articles about every Trump tweet. Trump will do inflammatory tweets. Some might be in the middle of the night. Everyone knows that he does this. It’s not surprising anymore. Therefore, it is not incumbent on the journalist to treat every instance of this as a major news item, just like you are not required to treat every politicians’ PR release as a major news item. Journalists should dictate the terms of their coverage, not Trump.

– You don’t need to treat every Trump tweet as 100% literal. Most of the time Trump is, pardon my French, just “bull-shitting.” He muses, he riffs, he does these extemporaneous stream-of-consciousness rants…So if Trump muses about some nutty idea on Twitter, it doesn’t mean that he plans to actually implement this idea in terms of government policy. He could just be trying to get a rise out of people. And it usually works.

– You are allowed to simply ignore Trump tweets. This may sound like a novel idea, but you are under no obligation to even pay attention to every Trump tweet. As a journalist, you are allowed to focus on other things… Hysterically over-reacting to every Trump tweet helps Trump. When you treat today’s loony Trump tweet as the top news story… you are keeping him at the center of attention, which he obviously craves. But you are also… strengthening his grip over the media, and you are making the media appear helpless and servile.

The core problem of Trump coverage, one that is rarely acknowledged or dealt with, is that because bad publicity helps Trump, there seems to be no way to criticize him without further inflating him. The moment you pay attention to him, he has won. And since it seems impossible not to pay attention to him, he will therefore always win.

That may make the situation seem impossible. It’s only impossible, though, if the media continue to follow the same set of rules for coverage that they have always operated under. If it always merits attention when important people do outrageous things, then Trump will dominate the media forever, because Trump knows how to increase his importance and knows how to be outrageous. The rules of what’s important must change if we are to successfully reduce Trump’s dominance of the press. That means apportioning more coverage to, for example, Saudi Arabia’s ongoing bombing of Yemen, and less coverage to whatever 140-character idiocy Trump has most recently spewed. It should be recognized that Trump is intentionally trying to get people to pay as much attention to him as possible, and that one needs to find a way not to give him what he wants.

But finding effective ways to apportion critical attention to Trump means more than just ignoring some of his more rancid Tweets. It also requires ridding ourselves of certain kinds of criticism, which frequently seem damning in their content but aren’t damning at all in their ultimate consequences.

Let’s, then, go through a few insults and criticisms of Trump that don’t seem to work very well. A few of the most obvious:

- Trump is orange

- Trump is vulgar

- Trump is dumb

- Trump has funny hair

These are all given frequent mention. They are also beside the point. One should care far more about what Trump thinks and does than what he looks like. Now, one could say that what he looks like is in some ways a reflection of who he is, since the ridiculous spray-tan with the little white eye-regions is the product and consequence of his vanity. But the broader principle of progressives should be: what someone looks like is of minimal relevance in evaluating them. That’s what we believe. And we should be consistent in that belief. If someone made fun of our candidate’s appearance, no matter what that appearance was, we would declare that as a matter of principle, image should matter less than substance. Such high-mindedness is both admirable and correct. But it has no force unless you maintain it consistently, even as applied to people whom you detest. (Furthermore, mockery of Trump’s mannerisms and appearance has the perverse effect of building him up into more of an icon than he already is.)

This is why the “Naked Trump” sculptures, which a group of anarchists erected during August in American city parks, were so politically useless. The sculpture depicted Trump as grotesquely flabby, his penis so minute as to be invisible to the naked eye. Entitled “The Emperor Has No Balls,” the statue’s artistic point was to humiliatingly “expose” Trump. But the message didn’t really make sense. Some people critiqued it as “transphobic,” a bizarre line of argument. The real problem with it, though, was that it didn’t actually make a serious point. Trump is fat. So what? Do we hate fat people? Do we want to reinforce the idea that being fat is gross? Trump has a small penis. So what? Do we want to maintain the cruel idea that penis size says something about one’s dignity? And how would we feel about a similarly unflattering nude Hillary Clinton sculpture? Mocking his body is a satisfying form of lashing out at Trump, but it’s not a particularly noble, persuasive, or progressive one.

In fact, one should also be wary of progressive attacks against Trump that are based on premises that progressives do not actually share. For example, there have been critical press articles (by liberals) about Melania Trump’s skirting of immigration law, Trump’s lack of familiarity with the Bible, and Trump’s evasion of the Vietnam draft. But progressives don’t want immigration status to be an issue, and they don’t care whether political candidates have read the Bible. And we’re the ones who are supposed to be sympathetic to those who wanted to avoid being killed in Vietnam.

These attacks are therefore not honest reflections of our values. Of course, the progressive response is that these critiques of Trump are about hypocrisy, about his own standards. Because Trump is anti-immigrant, it makes sense to call out his wife’s own violations of immigration law, or his own employment of unauthorized workers. Because Trump is pretending to be religious for the purposes of running for office, it makes sense to point out his pitiful knowledge of Biblical lore. Because he is warlike, we can point out that he’s a chicken. (Likewise with the sculpture: because Trump is a narcissist, it makes sense to point out that he is unattractive. Not that we care. But he does.)

There’s something a little bit uncomfortable about dwelling on these issues at all, though, because it’s hard to simultaneously insist that something matters for the limited purpose of proving hypocrisy but ultimately doesn’t matter in the least. If we call Trump a small-penised, nonreligious, draft-dodging employer of illegal immigrants (and one who is not even a billionaire at that!), we are willingly adopting a set of values that we don’t hold. And it may be difficult to turn around and insist that actually, those things are fine. Thus while it makes logical sense to make such critiques, it muddies progressive messaging. One’s time is probably better spend pointing out how Trump doesn’t live up to a set of good values that we do hold rather than a set of bad values that he himself pretends to hold.

A useful question to ask when criticizing Trump is as follows: would I care about Thing X if someone on my own side did it? For example, isn’t it true that if someone on my side had bought concrete from someone with criminal ties, I would be taking pains to explain why buying concrete from someone unpleasant doesn’t make you yourself unpleasant. Likewise, I do not care when Democrats have unfortunate haircuts. What matters to me is what someone believes, not whether their flesh is or is not the color of a ripe Satsuma.

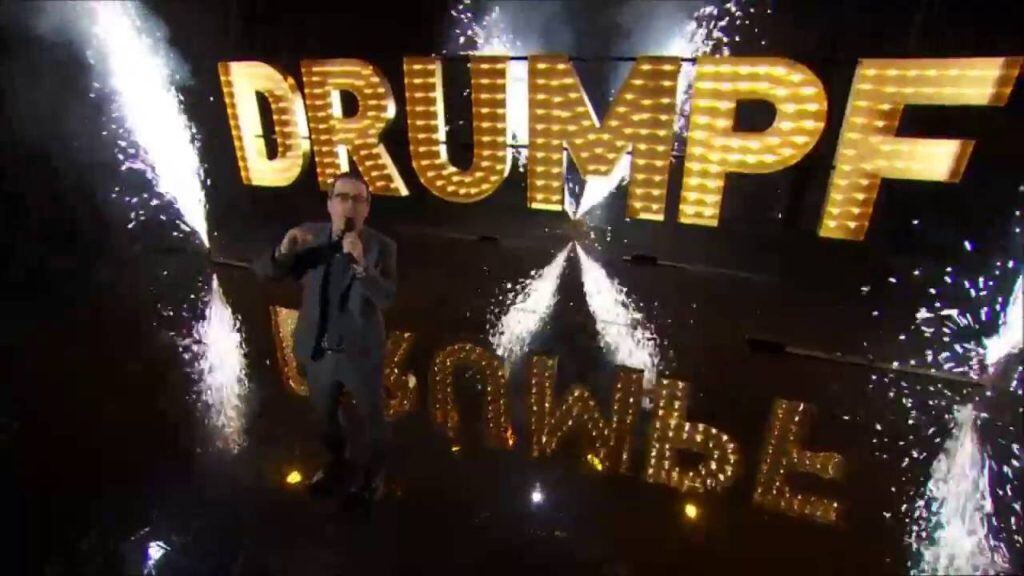

This is why John Oliver’s mockery of Trump on Last Week Tonight was particularly toothless and pathetic. Having found out that Trump’s German ancestors were called “Drumpf” rather than “Trump,” Oliver led a campaign to “Make Donald Drumpf Again,” wringing great amusement out of the apparent silliness of Trump’s ancestral name. But what was the point of this joke? What did it say about Trump? Lots of people have foreign ancestors with unusual names. Do we care? Isn’t progressivism supposed to have, as one of its principles, that foreign names aren’t funny just because they’re foreign? Isn’t this the cheapest and most xenophobic of all possible jokes? Oliver’s Drumpf campaign became extremely popular, but it was deeply childish. It fell into a common trap of Trump critiques: it descended to Trump’s level, using name-calling and playground taunts rather than trying to actually critique the truly harmful and reprehensible things about Trump. (It is possible to do satirical comedy that is actually brutal. The best joke about George W. Bush was nothing to do with My Pet Goat or his choking on a pretzel, but was the Onion’s devastating headline: “George W. Bush Debuts New Paintings Of Dogs, Friends, Ghost Of Iraqi Child That Follows Him Everywhere.”)

The critique of Trump as “vulgar” is another especially ineffective angle. Trump’s vulgarity is actually one of his only positive qualities. Vulgarity can be refreshing. It can get to the point, and be emotionally honest. It’s also nice to be told what politicians really think, in language that doesn’t try to disguise cruelty beneath a thin cloak of civility. As Amber A’Lee Frost writes, vulgarity in itself can have a clarifying effect:

Trump’s vulgarity is appealing precisely because it exposes political truths. As others have noted, Trump’s policies (wildly inconsistent though they may be) are actually no more extreme than those of other Republicans; Trump is just willing to strip away the pretense. Other candidates may say “national security is a fundamental priority,” whereas Trump will opt for “ban all the Muslims.” The latter is far less diplomatic, but in practice the two candidates fundamentally mean the same thing. We should prefer the honest boor, as polite euphemism is constantly used to mask atrocities.

Frost also points out that “vulgarity is the language of the people” and can be “wield[ed] righteously against the corrupt and the powerful.” Of course, much of Trump’s vulgarity has no such redemptive quality, and is used in the service of power rather than to undermine it. But it’s still more important to critique the underlying sentiment of Trump’s views rather than the coarseness with which Trump expresses them.

The failure to distinguish between tone and substance afflicted coverage of the notorious Billy Bush tape. Multiple news outlets reported that Trump had been caught on tape making “lewd” or “vulgar” remarks about women. In fact, he had been caught on tape bragging about committing sexual assault. The problem wasn’t the vulgarity. (After all, it would have been unobjectionable if he had been caught on tape saying “there’s nothing I love more than when someone gives unambiguous and enthusiastic consent for me to grab her by the pussy.”) It didn’t matter that he had said the word “pussy,” it mattered that he had admitted to a series of outrageous sex crimes. But the idea that “vulgarity” is what’s unappealing about Trump suggests that if he did the same exact things, with a little better manners, his behavior would be beyond reproach.

Calling Trump dumb is a similarly futile line of attack. First, nothing reinforces perceptions of liberals as snobs more easily than picking on stupid people. When Trump is mocked for his pronunciation of “China” or compared with the President from Idiocracy, critics miss something important: Trump may be an idiot, but he’s no dummy. That is to say: treating Trump as if he is slow leads to underestimating the kind of genius he has for successful PR manipulation. People will analyze the reading-level of Trump’s speeches, and conclude that he has the mind of a fourth-grader. But if you treat Trump as a fourth-grader, you may assume (quite wrongly) that he is easily outsmarted. Up until this point, underestimating Trump has produced nothing but misfortune for the underestimators. Trump should be treated as what he is: non-literate, non-worldly, but media-savvy and ruthlessly cunning. “Trump is dumb” messages are likely to play about as well as “Bush is dumb” messages did during the Bush/Kerry fight. They make liberals seem haughty, and Trump can claim that the elites are sneering at him (and by, implication, the working class) for his lack of formal learning.

Some critics of Trump seem to almost want to goad him into being worse for progressives. For example, in the time following the election, Trump was attacked for refusing national security briefings and retaining executive producer status on The Apprentice. The premise here, apparently, is that we want Donald Trump to spend less time working on reality shows and more time exercising the power of the presidency. But that seems an insane thing to desire. For progressives, it would probably be better if Trump spent four years continuing his reality show act than if he started thinking about which countries he’d like to bomb. The fewer national security briefings he gets, the better. (Same logic applies to the wall. Here’s a quick tip that all progressives should follow: if he doesn’t make an effort to build the wall, don’t tell him he’s a hypocrite and a failure.)

Likewise with Trump’s self-enrichment. A number of people have dwelled on his “conflicts of interest,” suggesting that Trump will unconstitutionally use his new powers to seek new business opportunities abroad, exploiting the office for financial gain. But if we’re being honest, this is probably the best outcome progressives could hope for. We should pray that Trump wants money rather than power, because building hotels in Singapore is one of the least destructive possible uses of his time. Corruption may be bad, but for progressives who care about human rights, Trump’s corruption should be very low on our list of worries. As Noam Chomsky has pointed out before, we should always hope that strongman-leaders are corrupt. If they’re corrupt, they might not do too much harm; you also can buy them off with money. But if they’re sincere yet megalomaniacal, there’s no end to the evil they will do. A corrupt con man will drain your treasury, but an honest ideologue could massacre six million people.

The question anyone writing about Trump should think about before making a criticism is as follows: does anybody really give a crap? For example, which do people care more about: Trump being friendly with Putin or about the potential disappearance of their Medicaid benefits? Do they care more about Trump tweeting some slur about a news anchor, or about the threat of nuclear war? Focus should be kept on those things that affect people’s lives the most.

There are bad potential critiques of Trump at every turn. When Trump negotiated with the Carrier air conditioner company in Indiana, arranging for them to keep 800 jobs in the United States in return for a tax break, some pointed out that 800 was only a fraction of the jobs in Indiana’s manufacturing sector. But this was a foolish critique. After all, 800 may not be many jobs statistically, but it’s a lot to the people working those jobs. Trivialize that number and you trivialize those people’s experiences. And saving 800 jobs was pretty impressive for a guy who hadn’t even been sworn in yet. Scoffing at the number seemed bitter and out-of-touch, and the grumbling appeared to implicitly concede that Trump had accomplished something.

But there was a far better critique to be made: Trump had essentially arranged for the company to receive an enormous bribe as a reward for threatening to send jobs to Mexico. It was a deal that looked good but set a terrible precedent, because it signaled to corporations that Trump would help to arrange for taxpayers to give them money to stay in the United States. The Trump Carrier deal was a PR masterstroke, but there was a serious and effective criticism to be made of it.

One person who understood how to criticize the deal effectively was Bernie Sanders. In the Washington Post, Sanders wrote:

Today, about 1,000 Carrier workers and their families should be rejoicing. But the rest of our nation’s workers should be very nervous. In exchange for allowing United Technologies to continue to offshore more than 1,000 jobs, Trump will reportedly give the company tax and regulatory favors that the corporation has sought. Just a short few months ago, Trump was pledging to force United Technologies to “pay a damn tax.” He was insisting on very steep tariffs for companies like Carrier that left the United States and wanted to sell their foreign-made products back in the United States. Instead of a damn tax, the company will be rewarded with a damn tax cut. Wow! How’s that for standing up to corporate greed? How’s that for punishing corporations that shut down in the United States and move abroad?

Note what Sanders did not do. He did not criticize every aspect of the deal. He did not diminish what it meant to the workers whose jobs were saved. But he reversed the message: instead of a move to help workers, it was a handout to corporations. This is the correct approach. It doesn’t treat every aspect of everything Trump does as necessary of the same criticism. Instead, it asks: how do Trump’s actions affect people in the real world? And if Trump’s actions affect people negatively, they should be criticized.

It’s possible to conduct effective messaging against Donald Trump. During the campaign, unions and independent groups recorded a series of devastating video ads featuring Trump’s workers and contractors, explaining the various ways in which he had screwed them and hurt their families. If they had been run across the country, they might have been very effective. (The Clinton campaign didn’t do anything with them.) Donald Trump has very low favorability ratings, and it should be relatively easy to expose him as a con man, one who offers working people promises that he has no intention of fulfilling, who says he will “drain the Washington swamp” and then stuffs his administration with parasitic billionaire elites.

But mounting effective attacks against Trump requires caring about being effective to begin with. The more Democrats spend time talking about things like, say, Trump angering China with a phone call to Taiwan (isn’t the left supposed to favor talking to Taiwan?), the less we’ll zero in on Trump’s true political weaknesses. Trump wants us to talk about his feud with the cast of Hamilton. He does not want us to force him to talk seriously about policy.

Criticisms should be of the things that matter: the serial sexual assaults, the deportation plans, the anti-Muslim sentiment, the handouts to the rich, the destruction of the earth. These are the things that matter, and if progressives actually do care about them, then these are the things we should spend our time discussing. Forget the gaffes. Forget the hypocrisy. Forget the hotels. Forget the hair. And don’t bother calling him Drumpf.

This article is adapted from the forthcoming book Trump: Anatomy of a Monstrosity. Pre-order today for shipping January 20th.