The Toxic Legacy of Martin Peretz’s New Republic

Jeet Heer discusses the publication that was once “the in-flight magazine of Air Force One,” which he says “promoted many of the worst decisions in modern American history.”

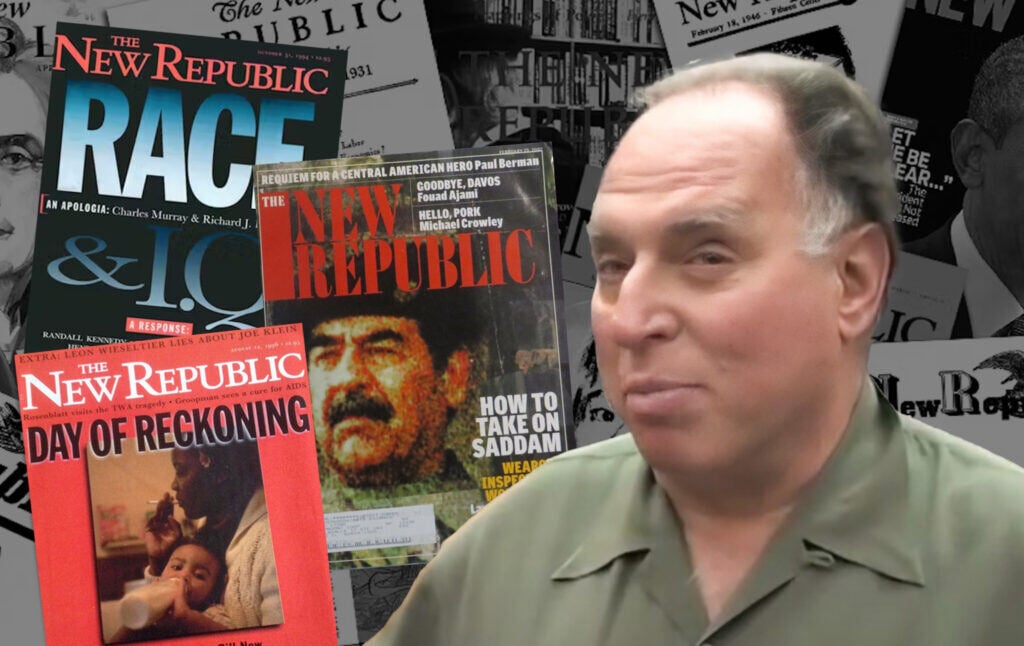

Jeet Heer has written two major essays about the intellectual legacy of the New Republic magazine’s 70s-2000s heyday. The first, from 2015, excavates the magazine’s history of racism and its role in Clinton-era “welfare reform” and in pushing Charles Murray and Richard Herrnstein’s The Bell Curve into public consciousness. The second piece, published recently, looks more broadly at the career of New Republic owner Martin Peretz: his racism, his hawkish foreign policy, and his role in creating the conservative “New Democrats” of the 1990s, who abandoned FDR-era liberalism.

Jeet joins us today to tell us more about why this magazine once mattered, and the enormous effect that such a small publication and a single man have had on the politics of our time.

NATHAN J. ROBINSON

To give people some background here, the New Republic magazine was once very important and influential. It had been called, in the 1990s, “the in-flight magazine of Air Force One,” which I think it actually may have been. You have written a couple of really interesting things on the rise and fall of the influence of this magazine. In 2015, you wrote a major piece for the New Republic itself, which was kind of exorcising the magazine’s a long history of publishing, well, racist bullshit, which is called “The New Republic‘s Legacy on Race.” Under new ownership, they wanted to grapple with, I guess, what they had done. So you wrote this remarkable piece where you dive into the entire history of the magazine. You have now written this piece that is sort of a book review, sort of an essay, on the longtime publisher of the New Republic magazine, Martin Peretz, and his memoir called The Controversialist. You write about the memoir, which you say is very good, but you also point out that he is a horrendous person and that this magazine has published a lot of horrendous stuff.

The question I want to start with is: you pointed out on X recently that the defenders of Martin Peretz, and the influence of Martin Peretz, seem to have disappeared from the world. Some young people who may be reading this may wonder, why did anyone ever think the New Republic mattered? So, could you begin with laying out what this magazine and this man once was?

HEER

Absolutely. Just to qualify what you just said a little bit, even though no one defends Marty Peretz—he’s now widely seen as a pariah and that’s actually a theme of his autobiography: “why have I become late-in-life marginalized?”—weirdly, his politics are still very influential. Very many important people in the world, including Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Head of the Department of Justice Merrick Garland, who were basically protégés of Peretz, are still in some ways influenced by his politics.

So, in part, there’s an interesting distinction between the rise and fall of the man, and the continued prevalence of his politics, even though it’s a politics that dares not speak its name. It’s a politics of neoliberalism. We now live in an era where neoliberals no longer will say that they’re neoliberals.

But just to say why he was influential, think about the long trajectory of the Democratic Party in the 20th century: the rise of the New Deal, that powerful coalition that reshaped America, was then expanded beyond economic liberalism towards racial equality with the civil rights movement, and then with the crisis of the 1960s, that coalition splintered and then reformed itself and a new politics emerged, which is given various names—I think neoliberal is as good a name as any—and was a kind of liberalism that abandoned many of the earlier commitments towards economic equality with the New Deal, retrenched on issues of civil rights, became increasingly critical of things like affirmative action and welfare spending, increasingly castigated African Americans as the authors of their own misfortune, and then sometimes flirted with scientific racism.

It’s also a liberalism that abandoned the earlier liberals’ ideals of internationalism and of working through international organizations and has become increasingly hawkish and nationalistic, particularly regarding Israel, carving out an exception for Israel to basically violate norms of international law that liberals themselves have created. The liberal international order created by Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman was suddenly abandoned for a politics of hawkish militancy, unchecked by any pretense of international law.

Martin Peretz was a key figure in creating that politics. He had started off as a member of the New Left and was actually involved with the anti-war and civil rights movements. In 1966-1967, he was involved with Martin Luther King Jr. and encouraging Dr. Spock to run against Lyndon Johnson. But then, at that moment in the late ’60s, he turned against the New Left and increasingly moved to the Right in a trajectory that has many parallels with many other prominent figures. And then, with the magazine, the New Republic promoted his politics. As an individual, he existed on the intersection of many key social networks.

ROBINSON

Yes, he’s a fascinating figure. I’ll just quote the New York Times review of his book. They say,

“He knew nearly everyone who mattered in the intertwined worlds of journalism, academia, and government. Martin Luther King, Jr. came to his house for dinner. He was Al Gore’s first phone call after Gore lost the 2000 election. Yo Yo Ma played at his birthday parties. Norman Mailer punched him in a Provincetown restaurant. This is scratching the surface of the surface.”

You point out that he had many proteges; he was not only the proprietor of this very influential magazine, but he was also a professor at Harvard for many decades, and he had a lot of students that went on to become big names in the power elite, with people on Wall Street like Jim Cramer, Lloyd Blankfein, and even the infamous billionaire Bill Ackman, and then people in the world of journalism and major pundits, and then politicians. This guy had a lot of connections. He was at the center of the power elite.

HEER

Absolutely. Basically, he was able to carve out a series of social networks that started with Harvard, had tendrils into journalism, including very famous journalists who became prominent at CNN and the New York Times and elsewhere, but also to political figures, like Al Gore and Joe Lieberman, and also at Wall Street. And to basically understand all these social networks, you have to understand that this is one of the greatest social climbers of all time. He’s almost like a hero of a 19th-century novel: the young man from the provinces who marries his way up and becomes a powerful figure.

Now, he had started off with a family that was of immigrant background in the 1930s and 1940s, where Jews were still marginalized in American society. But his father was well-to-do enough to be a landlord and to rent a factory. Peretz, through marriage, really rose in the world. And this is a little bit interesting. One of the facts that emerges in the book is there have been long-standing rumors about Peretz’s sexuality, but in the book, he openly identifies himself as gay. Not as bisexual, as gay. But he does have two marriages. The first was to a Florida heiress whose family had citrus money and who introduced him to the social world of New York intellectual and celebrity life. So, when he married his first wife, he started throwing parties where actors like Shelley Winters would appear.

And then subsequently in 1967, he married his second wife, Anne Farnsworth who, as he describes, it is not quite a Rockefeller but just a little bit near the ballpark of being a Rockefeller. Her family money goes back to the Singer sewing machine. Her family were great collectors of art. The story I tell is, when she was a student, she loved this painting that her grandfather owned and would go to his house and look at it and wrote a term paper about it. Her grandfather, in his will, left the painting to her, and it was a Rembrandt.

So, with Peretz’s second marriage, he really enters into this fabulously wealthy world, which gives him a very unique position. At Harvard, he was a lecturer and an associate professor—he was never tenure track—and the Harvard faculty all said, “you’re not really a scholar, you’re something else, but we would like to have you around.” They liked to have him around because of his money. So, it’s not normal that someone who’s a lecturer at Harvard is hobnobbing with the president of the university, but he was normally holding these salons with top faculty at Harvard. This is how elite reproduction happens in America, and he understood this.

At Harvard, he was able to recruit all these very talented young people like Michael Kinsley to join him at the New Republic, along with people who would later go on to have influence in the political world. And also, I think the real revelation of the book is something the people who followed him knew about, but maybe the wider world didn’t, which is his Wall Street connections. Some of his students became very active in Wall Street, and particularly in what we’ve called the “greed as good” era of 1980s Wall Street, with deregulation and junk bonds. He was very close friends with Ivan Boesky and Michael Milken. Boesky was convicted of insider trading, and Milken of securities fraud, and they were really emblems of the era where Wall Street went out of control and became this kind of unchecked power and we saw the financialization of the economy.

All these factors, these different worlds, interlocked in a very powerful way. He was heavily involved with something called the Democratic Leadership Council, which is these wealthy Wall Street people working to push the Democratic Party to the right, to nominate centrists like Bill Clinton and Al Gore. It was a new Democratic Party, one that cut off its ties from the labor movement which was in decline, which was much more hostile to the civil rights movement and openly distanced itself from figures like Jesse Jackson, had accepted a sort of Cold War militarism and deregulation. Basically, it was Reaganite, except on social issues. It was still committed to reproductive freedom and then embraced marriage equality, but it was basically the centrist Democratic Party. It is a very powerful social network that changed America.

ROBINSON

You point out he’s basically an open elitist, and also racist, which we’ll get into. But when he is the proprietor of this magazine, he doesn’t really try to hide the fact that he wants to hire white men from Harvard. I think you have the quote from the guy who said something like, “I was an affirmative action hire there because I went to Princeton.” That’s how bad it was. It’s all white men from Harvard, with very little respect for female editors and very few Black editors.

HEER

People might be able to check me on this, but I actually feel that under his long tenure at the New Republic, there was not, as far as I could ever find, a single Black editor. If someone can find one, I’m open to being critiqued on that. But basically, he was hiring his students from Harvard. And then they had Robert Wright, who was briefly the editor when one of the editors went away, and he was considered affirmative action because he was a Princeton man.

But this goes through his whole theory of American society and American politics, which came out of the new experiences in the 1960s. In the ’60s, he had been aligned with the New Left and then basically had a very bitter experience with this New Politics conference in Chicago in ‘67, where he was trying to unite the Black Freedom Movement and the anti-war movement, and he basically found that the student activists and the Black radicals didn’t respect him. In his memoirs, he says, they treated me as Mr. Moneybags, as the guy paying the bills, but they didn’t necessarily want to listen to me.

And I think that this pushed Peretz not just to the Right but to this new idea of politics. Politics is no longer mass movements; it’s no longer that you want to get the street politics of the Black Freedom Movement or the anti-war movement. What you want to do is cultivate the elite. The way he describes it in his memoir, the goal was to humanize the technocracy, to take the budding flowers of Harvard and mold them to be the right liberal politicians who will know the problems in society, but also know you can’t go too far—you can’t be too radical. And so, his project was exactly to create an American elite that was liberal but not too liberal. That’s maybe one way to put it.

ROBINSON

I want to talk about the New Republic itself. Although his tenure at the New Republic became famous, or infamous, and during that period it was very influential, the New Republic obviously predates him. So, give us some context and background on this magazine before he comes in to head it.

HEER

In some ways, one could argue that the elitism of the magazine was there from the start. It was started in 1914 by a group of Harvard undergraduates, and I believe they actually started it in the living room of Theodore Roosevelt, also a Harvard man. The idea was that it was a progressive era, Woodrow Wilson was in office, and that they wanted to also help promote these ideas and also promote the liberals within the Republican Party.

ROBINSON

So, Harvard, liberal, and racist was there from the beginning….

HEER

I think the characteristic figure was Walter Lippmann, who had sort of started off as a socialist, but it was really this idea of elite liberal technocracy. Now, having said that, liberalism itself goes through changes, and I think starting the 1930s in particular, they started to take in many more working class and African American voices—W. E. B. Du Bois writes for them—and in the New Deal era, they took on a more radical edge.

But the deep origin of the magazine is this idea that they wanted a magazine that was a kind of newsletter for the elite, for the policymakers, with the idea that real politics is not just to win elections, it’s influencing the people in the bureaucracy and in the government. But having said that, it became a very standard liberal magazine in the ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s with the sort of politics of both the New Deal and then later the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

But when Peretz took it over, he basically really oriented it in a much more right-wing direction. The argument was that he wanted to toughen liberalism, as he once told the Washington Post, make it more aggressive and more sharply argued, but also be willing to take in some conservative ideas, especially in terms of arms funding, more military funding, more willingness to have more policing, and more willingness to cut back on the welfare state. So, that was basically the politics. His politics in the ‘70s and ‘80s, as the American society was moving to the Right, was one that more Democrats were willing to listen to, but they had in the New Republic a really cogent sort of magazine that was really pushing it forcefully.

ROBINSON

Obviously, it’s very difficult to disentangle the influence that a magazine had versus the extent to which it reflects prevailing intellectual currents of the time, but tell us about the kind of role that the New Republic came to play. There was a kind of famous phrase, which begins with, “Even the liberal New Republic says…” The New Republic, because it was not a Reaganite publication but consistently a Democratic-leaning Clintonite publication that published a series of very hardcore right-wing ideas, could serve to legitimize right-wing ideas within liberals bases.

HEER

Absolutely. The classic phrase used in the 1980s, “Even the liberal New Republic,” meant: even the liberal New Republic says we have to fund the Contras in Nicaragua; even the liberal New Republic says we have to cut welfare; even the liberal New Republic says we need more spending on nuclear weapons. It serves that role of preserving the shell of a Democratic identity to promote conservative ideas.

The New Republic had a lot of fans within the Reagan White House; the conservative columnist George Will praised it often; Rush Limbaugh would praise it in the ‘90s. They all praised it with a very clear understanding that this was a magazine that could reach people that they couldn’t reach. People who would dismiss Rush Limbaugh, Reagan, or George Will would read the New Republic and say, “this is right.” The other aspect of influence was that so many of the people who wrote for it went on to have prominent media careers, especially with television coming to prominence—with cable television, particularly—which created many more new jobs for pundits.

So, a lot of the people at the so-called liberal New Republic would become someone like Michael Kinsley, who would go on Crossfire and play the liberal. But Michael Kinsley’s favorite politician was Margaret Thatcher. So, your voice of liberalism was a Thatcherite. But also, I would mention people like Fred Barnes and Charles Krauthammer, all of whom started at the New Republic and went on to Fox News and elsewhere and would write columns for the Washington Post. So, it was really a seedbed for creating a new crop of right-leaning political figures, some of whom presented themselves as liberals, and I think the elitism fed into that.

An article from Esquire in 1985 notes that to work for the New Republic, the primary qualification is a Harvard education. Of the eight major editors on the masthead in 1985, four were white Jewish male Harvard alumni. One of the two women is from Radcliffe, and none are Black. But it’s not just that it’s reflecting the era. If you worked for the New Republic, you would often get jobs then at the New York Times and the Atlantic—figures like Andrew Sullivan would become your major media stars. So, it’s actually seeding the media with figures that are both right-leaning, and also come from this incredibly elitist background, with the class politics that come from a Harvard background. So, I think its influence was immense.

ROBINSON

You mentioned the legitimization of right-wing ideas among Harvard liberals. One of the most extreme examples is, of course, perhaps the most infamous episode in the history of the New Republic, which is when it published the excerpt of Charles Murray and Richard Herrnstein’s The Bell Curve, which argued that first there was a persistent IQ gap between Black and white Americans, and that that gap was partly genetic in origin. It then made an argument for a kind of stratified society in which everyone would know their place. It’s a horrifying piece of really nasty racist propaganda, and it was swiftly debunked. But as you noted in your 2015 piece, where you were going through and excavating the full legacy of the magazine on racial issues, the magazine had a central role in making The Bell Curve not just an obscure tract by some right-wing pundit and some psychology professor, but the centerpiece of a national discussion that is still well-known today.

HEER

Yes, absolutely. There were excerpts of The Bell Curve and articles by Murray in the National Review and Commentary, but they were just reaching the converted. The fact that the New Republic, this liberal magazine read by the Clinton White House, was devoting an entire issue to it, was central. There were staff protests. Most of the staff were against it, and it was only really Andrew Sullivan and Marty Peretz that were in favor of it.

But the other aspect is how they handled it. For The Bell Curve, it was not just that these two guys wrote a book. They had a massive budget—a public relations budget—from the American Enterprise Institute, which had been funding their research for years to the tune of hundreds of thousands of dollars. The whole idea of their marketing strategy was: we’ve got to get this out there and get people talking about it before it can get fact checked by the experts in the field. So, the book, even though it was not sent out to scientific reviewers in the scientific journals, was excerpted in the New Republic. And when the New Republic printed the critiques from the magazine editors, they were all journalists, so it looked like this was a work of scientific scholarship making this claim and here are a bunch of liberal journalists objecting. It was only one of the dozen or so people that responded in the New Republic to The Bell Curve that had any training in science and could launch to scientific critique, and that created a false impression that this was a work of science that people might have political objections to, whereas once the book got into the scientific journals, it was savaged relentlessly.

So basically, it was a marketing campaign on behalf of promoting scientific racism, and Peretz in his memoir basically says, I wanted liberals to start taking these ideas seriously and talking about them. As I document in my two pieces, there’s evidence of Peretz’s own racism which shows up in both his writing and in the magazine in general. The classic example is Stephen Glass, the famous fabulist who made up stories for the New Republic, but I think what is less often noted is that he made up stories that catered to Marty Peretz’s racist ideology. What happened was that at editorial meetings, Peretz would say something like, half of all the cab drivers in Washington, D.C., are Africans from Africa; why aren’t Black American cab drivers willing to take up the job? And then Stephen Glass wrote this completely made up story of cab drivers in Washington, D.C., saying he was in a cab driven by a Black African and then a Black man from America came in and tried to rob them. It was a total work of fiction, but it was designed to cater to Marty Peretz’s racism and this ideology that the problem is that American-born Black people aren’t willing to work hard.

ROBINSON

As you point out, a lot of this stuff was used as the foundation for the gutting of the welfare state by the Clinton administration in the 1990s. There are real and serious human consequences. The New Republic pushes stories of Black cultural pathology, and then there’s a policy response, which is that we need to just send people to work and discipline them and stop supporting these mothers who don’t want to do anything but sit around raising their children all day.

HEER

Yes. I think people forget this, but Bill Clinton once praised Charles Murray. Now, he didn’t praise Charles Murray for The Bell Curve, but he praised Murray’s earlier work showing that the supposedly pathological impact of welfare is that it makes people not want to work. And so, it’s interesting that the New Republic definitely helped legitimize Charles Murray, to the point that a Democratic president was willing to praise this guy who was an open scientific racist. That really shows you the pernicious influence of the magazine.

ROBINSON

Could you dwell a bit more on the magazine’s foreign policy commitments? Because, obviously, that’s the other half of it: it is both neoliberal and neoconservative.

HEER

I think there are two aspects. One is a kind of anti-communism. It revived the classic Cold War anti-communism in a period where people were becoming critical of détente. But also, Israel. Peretz himself says he’d been anti-Vietnam War. But people asked, then why are you supporting Israel? Henry Kissinger asked him this, and Peretz responded, well, my dovishness stops at the deli. That’s to say, my loyalty to Israel is where I stop being a dove. The magazine absolutely took a very hard line on all sorts of for foreign policy issues. Notoriously, in the 1980s it supported the funding of the Contras, which many Democrats opposed, and was seen as a key part of that.

And here again, the racism is key. His own view of both African Americans and of Arabs was they were people who are culturally deficient, and therefore, need to know their place in society. His worry, growing out of the 1960s, was that the Black Freedom Movement would align itself with Palestinian liberation, which is what we’re kind of seeing now.

I have these two quotes from Peretz which are very revealing. One is from 1994, when he said, “So many people in the Black population are afflicted by deficiencies. And I mean, cultural deficiencies, which Jews, for example, don’t have.” He’s referring to crack mothers and whatnot. The other one is from 1992, when Israel was bombing Lebanon and he told Haaretz that Israel is to “inflict a lasting military defeat that will clarify to the Palestinians living in the West Bank that their struggle for an independent state has suffered a setback for many years. The Palestinians will be turned into just another crushed nation, like the Kurds or the Afghans.”

So, this is basically a foreign policy that says we have to crush the Palestinians. Now, as I note, neither the Kurds, the Afghans, nor the Palestinians have ever accepted their lot to be crushed. They will continue to fight, and that perhaps shows the poverty of that worldview, more than anything.

ROBINSON

Let’s talk about how it all came to an end. Obviously, Peretz, as we’ve laid out, at one point had the ear of presidents. The magazine is at the center of American intellectual life, and that is no longer the case. The New Republic still exists, it still publishes, but it’s got a very different ideology now, or at least it has abandoned this kind of editorial line. It certainly doesn’t have the kind of influence and reach that it once had. I began this conversation by trying to get us to establish who he is because I think for many people, he’s just totally out of the conversation. But as you corrected me, his influence is still there. Yet his book, even though it got praised in the New York Times, barely sold any copies. I looked it up. I don’t think many people will read this memoir or are interested in what he has to say today.

So, how did he go from the heights of influence over the power elite to the margins?

HEER

There are several things that happened. And to your listeners and readers, I would say this is a book with a happy ending because for once, somebody gets their comeuppance.

So, one is that the New Republic, which usually backed the Iraq War, which turned into a disaster, actually backed Joe Lieberman for President in 2004, which showed how out of touch they were with the Democratic Party. Peretz himself had, amazingly, ruined his family’s fortune, which is a hard thing to do with a fortune that’s nearly the size of the Rockefeller’s. He had invested in Wall Street and got caught up in the dot-com bubble burst of the early aughts. That ended, as did his marriage to Anne Farnsworth Peretz. And then, increasingly, he would rely on other rich friends to help finance the magazine and was no longer the financial power he was. And this, I think, reflects very badly on liberalism—many people happily took his money and would not criticize him when he was writing the checks, but once he started to lose his money, many liberals turned against him, and you saw more vocal, liberal critique of his racism.

And so, there’s this beautiful scene at the introduction of the book, where he talks about how Harvard was going to honor him with an endowed chair in his name, and then Harvard students were protesting his racism. So, describing the scene, Peretz says:

“The invasion of Iraq, which I backed, is a disaster; the financial system that my friends helped build has crashed; my wife and I are divorced; The New Republic is sold after I feared going bust — and here I am in my white suit walking across Harvard Yard, surrounded by students: “Harvard, Harvard, shame on you, honoring a racist fool.” The racist fool is, apparently, me. It’s a sodden coda, one I don’t quite grasp, or believe.”

So, even though he doesn’t understand what’s happening to him, basically, everything he’s done has turned to crap. His friends, like Larry Summers and others, were busted. The Iraq War, his marriage, his family fortune, his magazine, and young people are calling him out for being a racist. And I have to say, there are images of that scene on YouTube—you can find it. I just want someone to take that image and add the Curb Your Enthusiasm song at the end because this is the ending that he deserved.

But having said all that, unfortunately, his influence is everywhere. I think that kind of right-wing liberalism he created still sees its influence in the Biden administration. Joe Biden himself, with his Zionism, is a kind of creation of this new era. Many of Peretz’s prodigies are all over the place. I think magazines like the Atlantic still have that sort of reactionary centrist politics. I think it’s shameful that liberals no longer avow Marty Peretz, and they have cut him loose. He’s like one of the guys in Mission Impossible: he has gone too far, and we disavow you. But he is still an influence, unfortunately.

ROBINSON

Yes, there was this kind of moment where I think a lot of people had to break from him when he came out and basically said, “I don’t know whether Muslims deserve First Amendment rights.”

HEER

That was the one thing, but, I have to say, if you go through the record, he was saying racist stuff like that all along. The cream of the liberal elite were willing to go along as long as he had his wife’s money. And only then, once that money was gone, did they turn their backs on him. We’ll take his money when he was a racist and then disavow him when he lost his money. What does that say about these liberal journalists?

ROBINSON

I want to quote a couple of things that you say here in your writing. Of his memoir, you write that “no other book so clearly illuminates the moral, intellectual and political corruption of neoliberalism.” Of the New Republic, you write that

it promoted many of the worst decisions in modern American history: the killing fields in 1980 Central America, the invasion of Iraq, the downgrading of diplomacy and preference to military solutions in foreign policy, the neoliberal economics that have fueled inequality and instability, the brutalization of the Palestinians, the revival of scientific racism, and the persistent whittling down of the welfare state.

And you note that this is only a partial list. Then, speaking of the influence, you write, “while you cannot solely blame Marty Peretz for everything that’s wrong in American life, he did play his part in making America a less healthy, less egalitarian, less free, and less enlightened place.” So, your ultimate verdict on this man, and the magazine under his tenure, is deeply damning.

HEER

Absolutely. Yes. And what makes his book actually great, and I would encourage listeners and readers to read it, is that on some level Peretz is aware of this. On some level, even though he still holds his old politics, he’s aware that the world he tried to create has turned to crap. And that makes it almost like a novel. I say it’s the best novel from an unreliable narrator since Lolita. It is a very powerful work, and it actually does show all his connections and how they work together. It really shows how the American elite operates. So, I think this is a case of “know your enemy.” We, as people on the Left, should understand who Marty Peretz is.

ROBINSON

Well, to achieve that understanding, they can do no better than to look in the Nation at your new piece, “Friends and Enemies: Marty Peretz and the Travails of American Liberalism.” And I also think it’s very much worth going back and looking at your 2015 piece, “The New Republic’s Legacy on Race: a Historical Reflection,” where you seem to read the entire archives of the New Republic, finding everything, including their take on rap music, where they said something about how rap music isn’t Black, isn’t music, and that rap’s hour as innovative, popular music has come and gone—they said that in 1991. A lot of the New Republic doesn’t hold up very well.

HEER

It’s interesting because even when they criticize Charles Murray—Leon Wieseltier, the book review editor, criticized The Bell Curve, but in his critique, he says that, unfortunately, this sort of stuff will help legitimize the awful street culture of things like rap music and Toni Morrison. So, imagine a magazine editor thinks that Toni Morrison—

ROBINSON

He’s the book review guy! Oh, and by the way, Wieseltier also has an ignominious end.

HEER

Yes, he does. This is the thing, if you want a happy ending, read about these guys because their downfall is great. An old professor I knew used to say that when he got depressed, he’d love to read the book The Decline and Fall of Nazi Germany because it was a book with a happy ending. Yeah, there you go.

ROBINSON

There you go. Put Marty Peretz’s book in that category. Actually, post-Marty Peretz, the New Republic does publish quite a lot of good stuff these days.

HEER

I worked for them after the Peretz era. And I will say that even in the bad days, they had very talented journalists. I’ll mention John Judis, Peter Beinart, Rick Hertzberg—they were some of the best liberal journalists who were writing against Peretz, but in the context where this magazine was promoting bad ideas and had some liberals to gain credibility. So, let’s give a little bit of credit.

ROBINSON

Credit to the editors during your tenure there for letting you write the piece on how racist the magazine had been for most of its career.

HEER

I actually think other publications should do the same. I think if you actually went into the archives of the Atlantic or the New York Times, you would find amazing articles. I think of this New York Times article saying how the “Negro cocaine fiend” is a new threat to America.

ROBINSON

One of the articles I’m proud of came from just looking in the New York Times archives for how they reported the rise of Hitler. I just found all the articles up to World War II, saying things like, Hitler’s not serious about any of this antisemitism stuff. You just go back, and it’s just extraordinary some of the things that they wrote. So, I agree. Every publication should get these skeletons out of the closet and have their reckoning.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.