What Jane McAlevey Has Taught Us

The labor organizer and writer is approaching the end of her life. She leaves behind vital organizing lessons that will reverberate over the next decades.

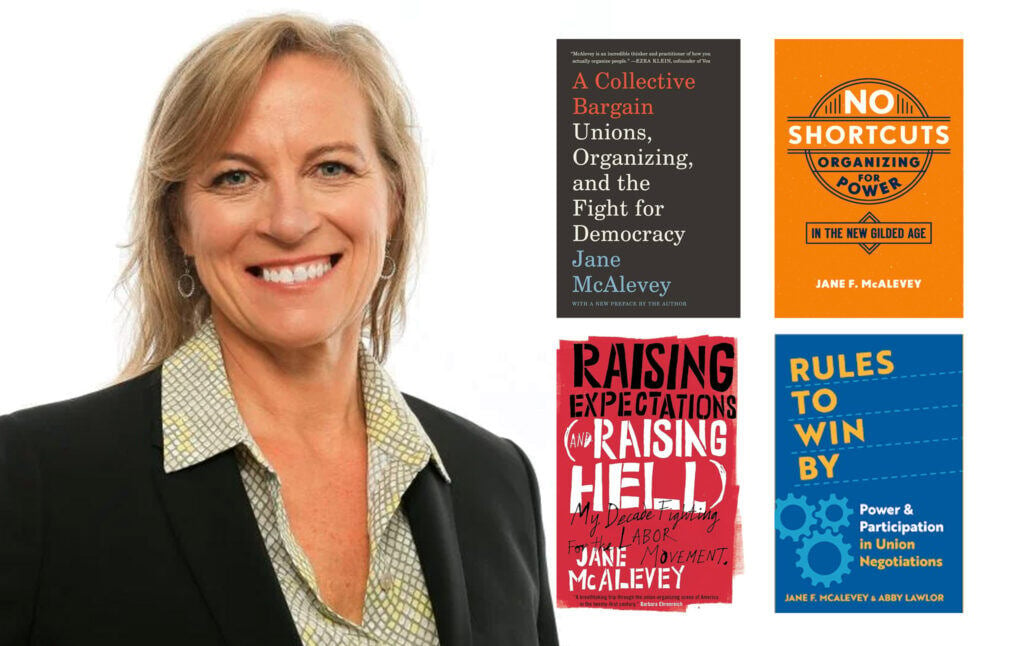

The veteran labor organizer and scholar Jane McAlevey recently announced that she is near the end of her life, after having been diagnosed in 2021 with incurable cancer. Losing McAlevey will be a major blow to the American left. As the New Yorker put it last year, she has been credited with transforming the U.S. labor movement, contributing to the rebirth of union organizing in our time after a long period of stagnation. Her work should be carefully studied, because she has done as much as anyone else to clearly explain the problem with the distribution of power in this country, and show practically how that distribution can be changed. Her books (Raising Expectations (And Raising Hell), No Shortcuts, A Collective Bargain, and the co-authored Rules to Win By) are going to remain classic handbooks on how working people can organize and win. McAlevey’s work combines stirring, urgent exhortations with detailed, case study-driven explanations of how a successful labor movement is built on the ground.

McAlevey’s writing is mostly strategic and programmatic, but she knows that before getting to the question of “how” to build a movement, we have to answer “why.” Why do we need a labor movement? Why should working people join unions? Why organize your workplace? The answers are not self-evident to everyone. Chapter 1 of A Collective Bargain begins by laying out what a union is in the simplest possible terms and showing why McAlevey devoted her life to helping workers form them. She quotes an old definition:

“What is a union? A collective effort by all employees who work for an employer:

– To stop the boss from doing what you don’t want him to do. Discharge, unfair layoff, promotion, speed up, etc.

– To make the boss do what you want him to do. More pay, vacation, holidays, health coverage, pensions, etc.

And, to be used in any other way the members see fit.”

McAlevey comments that “it really is that simple,” and “unions are conduits for worker demands and fairness in the workplace.” They can “leverage worker solidarity to not only prevent management from treating workers poorly, but to force management to create a safer, equitable, and more joyous workplace.” But unions, she explains, are not just good for the workers who are in them. They are also essential for the health of democracy, and strong unions are a necessary prerequisite of winning progressive economic policies. (This argument is also spelled out well in Hamilton Nolan’s new book The Hammer.)

A Collective Bargain systematically demolishes pernicious myths about unions. “For several generations,” McAlevey writes, “the idea of a union has been intentionally twisted, maligned, defamed, attacked, and systematically equated with the ‘last century.’” She laments that anti-union propaganda campaigns have been so successful over the past decades that even liberal friends “who wouldn’t dream of eating nonorganic food, who drive electric vehicles, send money to save Tibet, and marched wearing pink pussy hats complain that the teachers’ union is the reason public schools are deteriorating, or that striking transit workers ruined their commute, or that unions are the reason they can’t get an appointment this decade with their HMO.”

So she goes through the classic smears: unions are corrupt, meddlesome, bureaucratic, bigoted, anti-environmental, hostile to progress, etc., and shows how these myths have been pushed effectively by those with a strong financial interest in ensuring workers don’t realize how much more power they have when they organize themselves into unions. The “raising expectations” McAlevey spoke of means getting working people to believe that they deserve more than they are being given, helping people understand their own true value and demand that they be compensated in accordance with it.

Once we understand the importance of having a strong labor movement, the question becomes: how do we get it? This is where McAlevey’s books, talks, and articles are at their most helpful, and people will undoubtedly be consulting them for many decades to come. McAlevey has thought hard about questions of power: who has it, and how can you get it? If you don’t like some corporate practice or some government policy, changing it requires thinking about who makes decisions and how they can be forced to make different ones (or how the existing decision-makers can be swapped out for new ones). We can all go out into the streets and wave protest signs, but we need a theory of how that’s going to actually achieve an outcome. As McAlevey writes, it’s easy to see what the powerful do, but if we’re going to affect anything, we need to know more:

It doesn’t seem all that difficult to understand how today’s priestly-kingly-corporate class rules. But for people attempting to change this or that policy, especially if the change desired is meaningful (i.e., will change society), it is essential to first dissect and chart their targets’ numerous ties and networks. Even understanding whom to target—who the primary and secondary people and institutions are that will determine whether the campaign will succeed (or society will change)—often requires a highly detailed power-structure analysis.

McAlevey’s books explain how to do this kind of power structure analysis in whatever situation you find yourself in. She also helps us understand the distinction between things that only look like activism and actions that are actually likely to bring about change. (“Pretend power versus actual power.”) McAlevey advises on every step of the organizing process, including performing “structure tests” that help to measure just how much power you’ve actually built and whether you’re ready for particular high-risk showdowns. (She explained this further in a 2019 interview with Current Affairs.) McAlevey famously distinguishes between “mobilizing” and “organizing” (and the still-different “advocacy”). Mobilizing is when you get the people who are already loyal to your cause to show up, and organizing is when you actually expand the pool of people that are loyal to your cause. The distinction is crucial, because movements that only “mobilize” don’t grow. They may look active, because the people involved are very committed, but they have a hard time winning because they’re not drawing new adherents.

One of McAlevey’s tables clearly illustrates the distinction (along with a third approach, “advocacy,” which is even more elite-led and is outright hostile to mass participation:

McAlevey explains:

[Mobilizing] brings large numbers of people to the fight. However, too often they are the same people: dedicated activists who show up over and over at every meeting and rally for all good causes, but without the full mass of their coworkers or community behind them. This is because a professional staff directs, manipulates, and controls the mobilization; the staffers see themselves, not ordinary people, as the key agents of change. To them, it matters little who shows up, or, why, as long as a sufficient number of bodies appear—enough for a photo good enough to tweet and maybe generate earned media. The committed activists in the photo have had no part in developing a power analysis; they aren’t informed about that or the resulting strategy, but they dutifully show up at protests that rarely matter to power holders… [O]rganizing, places the agency for success with a continually expanding base of ordinary people, a mass of people never previously involved, who don’t consider themselves activists at all— that’s the point of organizing. In the organizing approach, specific injustice and outrage are the immediate motivation, but the primary goal is to transfer power from the elite to the majority, from the 1 percent to the 99 percent. Individual campaigns matter in themselves, but they are primarily a mechanism for bringing new people into the change process and keeping them involved. The organizing approach relies on mass negotiations to win, rather than the closed-door deal making typical of both advocacy and mobilizing. Ordinary people help make the power analysis, design the strategy, and achieve the outcome. They are essential and they know it.

At the end here, we can see another common theme of McAlevey’s writing, which is that workers themselves need to be in charge of their unions. Although McAlevey rebuts corporate myths about unions, she was also harshly critical of many contemporary unions for being undemocratic and unaccountable, their decision-making led by executive staff rather than the priorities of the members themselves. She writes that “the greatest damage to our movements today has been the shift in the agent of change from rank-and-file workers and ordinary people to cape-wearing, sword-wielding, swashbuckling staff.” While not denying that it’s important for unions to have skilled and experienced staff, McAlevey believed that the labor movement in the U.S. had faltered not just because a ruthless corporate war against labor has been waged for 40-plus years, but because a gap had grown between union leaders and members.

McAlevey has long advocated genuine union democracy, which she says is not only principled but also pragmatic. The strategic necessity of democracy is a major theme of her most recent book, Rules to Win By, co-authored with Abby Lawlor. In this book McAlevey and Lawlor look at how contract negotiations with employers work, and point out that winning recognition of a union is only half the battle. Once you’ve got a union in place, the employer’s union-busting doesn’t end, and they’ll frequently try all kinds of dirty tricks to prevent the union from successfully negotiating a contract. The book shines a light on these tricks and prepares unions to deal with them. It’s a kind of leftist equivalent of the famous negotiating handbook Getting To Yes, but unlike that book it assumes that the party on the other side of the negotiating table is powerful, ruthless, and trying to utterly destroy you. Rules to Win By argues that the best way to counter employers’ power in negotiations is to include workers as much as possible in the actual negotiating process, rather than having professional negotiators handle things in secret. Negotiations, they say, should be “big, transparent, and open,” meaning that a lot of people should be part of them, and workers should be kept apprised of everything that is being said and be able to attend. They explain how this departs from the typical approach:

While contract negotiations are an “unsexy” part of the labor movement, McAlevey and Lawlor argue that they’re critical to understand and master, because companies like Amazon and Starbucks have successfully thwarted unions in this second stage. The unions have bested the companies in the organizing stage, only to be beaten back when it comes time to negotiate a contract. As always, McAlevey’s mind was on the most practical and quotidian questions, the “hard work” that isn’t as much fun as singing “Solidarity Forever” and marching through the streets, but is essential to building power. I was lucky enough to interview McAlevey and Lawlor last year for this magazine’s podcast. Even though her health was in decline at the time, McAlevey was full of enthusiasm for the struggle. I began our conversation by putting to her something Vox had recently run claiming that the “resurgence” of the labor movement was overhyped. She wasn’t having any of it. It’s true that union density is still stubbornly low in this country. And yet, she explained: “the excitement is real and the mobilization of forces on the ground right now is actually quite substantial. The young people who are bringing energy into today’s revival moment, buoyed by the record high support for trade unions in the general public, has led to a more growing awareness, frankly, that there’s a real problem with union busting in the United States.” The New Yorker profile makes clear that McAlevey knew her time on Earth was probably limited (both her mother and sister had died young from aggressive forms of cancer), and she used every moment to try to advance the cause of labor and help working people find their strength. In our interview, she stressed again the necessity not just of “speaking truth to power,” but of analyzing the structure of power, because “the more people understand how power works, the more capable they are of actually overcoming the kind of obstacles that are thrown in their face along the way.” Her contribution to giving people that understanding is immense, and her books will continue to give people the tools they need to go on fighting the most important fight of our generation.