The Victories of the 20th Century Feminist Movement Are Under Constant Threat

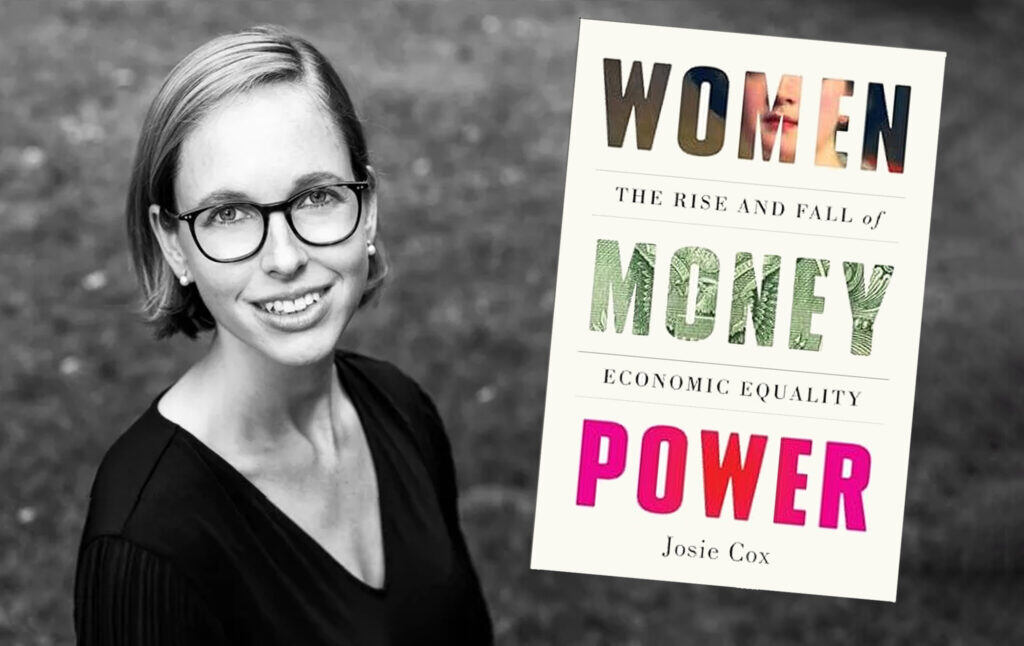

Journalist Josie Cox on what the women’s movement fought for and won—and the renewed reactionary threats of our time.

Journalist Josie Cox is the author of the new book Women Money Power: The Rise and Fall of Economic Equality, a history of the 20th century women’s movement that documents the remarkable courage of the women who gave us suffrage, abortion rights, and greater equality across many dimensions of social and economic life. Today she joins to discuss how those gains were made, but also the failures (such as the story of the Equal Rights Amendment). She also talks about how many of the striking victories for women’s equality are now under serious threat of rollback.

Nathan J. Robinson

I want to begin where you open the book, with the conversations you had with a CEO of a company with a “commitment to equality.” You peel back that “commitment” and show that beneath it can lie some lingering ancient stereotypes and prejudices. Could you tell us a little bit more about that?

Josie Cox

I would love to tell you more. And every time I tell this story, I am paranoid that I’m going to accidentally reveal the identity of who we are talking about.

Robinson

Now we wouldn’t want that, would we?

Cox

True to the code of conduct of journalism, we agreed that it was an off the record conversation, so unfortunately, one might say the identity of this person will never be revealed. That being said, I’d be delighted to tell you more about what happened during that conversation. This was a good year into the global COVID-19 pandemic. The backdrop was that what we saw in the labor market as a result of the pandemic was the sort of hardening and defaulting towards stereotypical gender norms, which meant that when childcare facilities around the world closed, schools shut up, and everything went into lockdown, what we were seeing more often than not was women essentially being primary caregivers, often taking a step back from the paid labor market to make sure that they were essentially keeping the home running and looking after kids. And we talked a lot at that time about how the COVID-19 pandemic was a sort of women’s recession, and that it was having all these detrimental impacts on gender equality in the workforce.

And so, when I had the opportunity to speak to the CEO, the first question that I asked this gentleman was how he characterized the gender pay gap within his organization; in his view, what was the reason why the gender pay gap was still so prevalent and so persistent within his organization. Now, the organization that he leads is based in the US, but it also has large UK operations, and since 2017, all organizations in the UK that employ at least 250 people have been mandated, compelled by law, to publish their gender pay gap by quartile. And so, I looked up the UK gender pay gap report that this particular organization had published most recently, and I assumed correctly that it was a decent proxy of what the gender pay gap across the rest of the organization looked like.

And so, I pointed towards these figures when I was talking to the CEO. I asked, why has your gender pay gap essentially not moved over the last few years? And he said to me two things. The first was, it’s important to understand that he never pays women and men differently for doing the same job, which, as we all know, under the 1964 Civil Rights Act would, quite frankly, be illegal. But what really floored me was that when I dug a little bit deeper, he said that it was really important that I understood that sometimes when a woman decides to start a family and temporarily takes a step out of the paid labor market to take maternity leave, that when she returns, sometimes she’s just not as professionally ambitious as a man in her position. And so, that planted the seed for me because I was quite frankly floored by the fact that he thought that was the most appropriate explanation provided for the gender pay gap. He was comfortable being reductive and simplistic in drawing that conclusion.

Robinson

Yes, it’s stunning. The quote you have here is, “sometimes when a woman temporarily leaves the workforce to have a baby, she doesn’t want to be promoted when she comes back,” which is interesting because, do you offer and she says “no,” or do you just assume that she probably doesn’t want to, so why even ask her if she’d like to be promoted?

Cox

That should have been my follow-up question. But yes, the way you’re reacting to that particular quote is exactly how I reacted to it.

Robinson

Obviously, it may be galling to hear something like that, repeating just an unbelievably common trope. As you point out, it is illegal to pay differently for the same work. What a lot of people conclude, from this CEO to many people who rationalize the gender pay gap in various ways, such as in the PragerU video by Christina Hoff Sommers, is that this means “there is no gender pay gap.” Because if for the same work you get paid the same amount, and it must be other factors. Those factors are “voluntary choices” that women make—they “want” different things—and it is not a result of companies choosing to pay differently for the same work. How do you respond to that?

Cox

Well, I think it’s important to understand that when you sort of look at the anatomy of the gender pay gap—and to be clear, when we talk about the gender pay gap, we’re talking about the average pay of a woman compared to the average pay of a man, which in the US is about 82 cents to the dollar—it would be wrong to say that the entire difference there, the entire gap, is because of discrimination or conscious bias that is going on in the labor market. That would be completely wrong to say. But there are so many different components to it, and there are certainly components to it that are not in accordance with the law. And I think one of the sort of overarching narratives that I come back to throughout the book is that I think of the law as this sort of very large fishing net, and the most egregious crimes get caught up in this fishing net: you can’t fire a woman for getting pregnant; you can’t fire a woman for getting married; you can no longer pay a woman and a man different amounts for doing the same job and having the same responsibilities at a company. But there are certain things that are much harder to quantify. I go into microaggressions and into individual hiring decisions. It’s very hard to delve into the reasons as to why one person is hired over another, and you can always make arguments that it is based on merit. And then there are heuristics biases, this one particular bias that I think is just so fascinating, and once you know about it, you feel like you see who resemble us, either physically or in terms of their mannerisms, and that is how we end up with pretty much every single CEO of every single Wall Street bank bar one being a white man.

Robinson

It’s so funny. The argument that we pay the same for the same work is treated as a serious response to the gender pay gap, but you have men in all the high-paying jobs and women in lower-paying jobs. Even if you “pay the same for the same work,” who’s doing which work?

Cox

Right. And I think that is actually a core argument as to why the gender pay gap in itself is just far too crude a measure to actually understand what we’re talking about here, which is just more sweeping inequality across the opportunities and the economic potential that women and men still have in the labor market.

Robinson

You mentioned, in your first response, the disruptive effect of COVID on gender equality. It made me think about the World War II chapter in your book, where you write about the entrance of women into the labor market during the war. You wrote about Rosie the Riveter—the real life Rosies you profile. One of the things that strikes me as consistent between both of those historical periods, and is also kind of reflected in your title, The Rise and Fall of Economic Equality, is that we tend to have this view of progress as linear, which is that women make gains and those gains don’t disappear. But one of the things you point out about World War II is there are a bunch of gains, but then disappear after the war is over.

Cox

Yes, absolutely. I’m glad you picked up on that. Even when I set out to report on this book, I thought, I want to do a sweeping history of female economic empowerment. And despite the fact that I had a reasonably good understanding of some of the key developments that have happened over the last 80 years, I still thought that generally we would have an upward trajectory.

But you’re absolutely right. Women had the opportunity and the duty to come into the paid labor market during the Second World War, and then essentially, as quickly as they came into the paid labor market, and as quickly as they realized that they were actually as capable of doing a lot of the paid work that men had been doing traditionally, they were defaulted back out of the paid labor market and into what I call the unpaid labor market, which is essentially running the household and looking after the kids. We have incidents of that happening throughout history, in every single sort of decade that I profile, be that the introduction of the ERA (Equal Rights Amendment), which then fails pretty spectacularly to get adopted into law.

As you mentioned, before COVID, female labor force participation was at the highest it had ever been. And then we see, again, pretty much overnight, this very dramatic sort of hardening of traditional values and traditional gender stereotypes. And of course, more recently, the war on reproductive rights in this country is the perfect example of that sort of rollercoaster ride of progress and setback, of rise and fall.

Robinson

Something I just hadn’t thought about until I read your book is that here in New Orleans we have the National World War II Museum just down the street, and they’ve gotten actually very good at covering the race and gender aspects of the war. There is a big tribute to Rosie the Riveter and what have you. I don’t think they cover the fact that Rosie the Riveter got a pink slip in 1945. All the men came home and said, that was great—look at you, you raised your fist. They sell so many of the Rosie themed goods in the gift shop at the World War II Museum—a great symbol of empowerment. But then you point out that the men came home and said, we’re not making bombers anymore, so now you have to go and be housewives.

Cox

Yes, absolutely. And I think one of the sort of saddest, most surprising things about the Rosies—there’s one particular Rosie the Riveter, so to speak, who I profiled in the book, who is a lady named [May/Mae] who lives in Pennsylvania, who is now 97. Absolutely super sharp memory, very passionate, very determined to tell the story of Rosie the Riveters and to sustain that legacy. She says that one of the hardest things was that when everyone was celebrating at the end of the war, she actually felt this lingering, deep sense of resentment that was completely a taboo. She couldn’t talk about it because how ungrateful would that have sounded to sort of complain about being unemployed and shoved out of the paid labor market at a time of great national victory.

Robinson

Throughout the book, you tell this story through profiles. You point out the really important fact that even when there is a kind of linear progress, or even when gains that are made can be sustained, they are the result of hard fights by women, and while some of their names are known in history books, many of them—as you write—aren’t.

Cox

Absolutely. And that was actually one of the greatest joys of writing this book, just really going down these rabbit holes and delving into these characters and lives that had such a massive impact on female economic empowerment, but whose names are completely obscure. It may be hard to choose a favorite, but one of the women who I particularly enjoyed researching was this woman named Katharine Dexter McCormick, who essentially ended up financing pretty much all the research and development into the first oral contraceptive pill that became available in the US. She was a fierce advocate for feminism, and a fierce advocate for birth control. She actually did work with Margaret Sanger, but her motivations were not eugenicist in nature. She was very much just of the opinion that women should have the opportunity and choice of when they want to start a family. Starting a family should not necessarily mean the end of a woman’s independence and the end of a woman’s prospect of having a career or a job. She has been completely obscured by history. No one really has ever heard of her name. She was also one of the first women to graduate from MIT, which is sort of remarkable in the very early 1900s. I went to MIT just to kind of see if I could find any traces or trails of Katharine Dexter McCormick, and I found some of her diaries in the archives and some of her notebooks. And then there’s the McCormick Hall, which is a dorm on MIT’s campus that she endowed. I stood outside McCormick Hall for about half a day, and I asked everybody going in and coming out whether they knew who McCormick was.

Robinson

Did you get any?

Cox

Absolutely not. Across the board, people just thought it was a rich dude.

Robinson

It’s funny because you say her name is not known. I, in fact, did not know about her until I read your book. But I realized that I had heard the name McCormick because I remember specifically in my high school history class, we were taught about the importance of the McCormick Reaper. And it’s the same McCormick.

Cox

Arguably, slightly less of a long-term impact on women’s economic rights than the contraceptive pill.

Robinson

But the point being that they taught us about the reaper, but they didn’t teach us to about Mrs. McCormick, married to a member of the family, and all of her accomplishments.

Cox

Absolutely, yes.

Robinson

It is the case, though, that thanks to women like Mrs. McCormick, there have been some incredible and real achievements in social progress. I don’t want to succumb to the alternative view, which is that nothing ever changes. When you dive into the history here, as you do, it is quite stunning what a different and vastly more oppressive and a horrible world in many ways these women had to live in and navigate and deal with.

Cox

Yes, absolutely. I think that is something that we really have to bear in mind and remember the context. One of the things I delve into in the book is this concept of coverture, which was a concept that came from British law that very much applied up until the late 1800s in the US— and into the 1900s, too, actually—which essentially meant that a woman was covered by the man in her life. So, when she was born, her identity was inextricably linked with the identity of her father. And as soon as she got married off, she was sort of passed on to her husband, symbolically giving the husband her hand in marriage. And so, it really wasn’t that long ago that a woman had absolutely no rights and no ownership over anything, not even her own body. We’ve certainly come a long way since then. That being said, I think the flip side of that is that, especially in the last five years in this country, we are seeing remnants of the past in quite obvious ways and scary ways. So yes, we’ve come a really long way in the past 100 years, but at the same time, again, it’s this narrative of the rise and fall.

Robinson

And it’s shocking to realize how recently things like spousal rape, denying women a credit card, or, as you discussed, firing a woman for getting pregnant, were legal in some states. The progress that there has been has often been within the lifetimes of people who are still alive today.

Cox

Yes, absolutely. As you say, the Equal Credit Opportunity Act was only passed in 1974. Until that point, a bank still had the legal right to refuse a woman credit, based on her sex alone. 1978 was the year when women officially could no longer be fired for getting pregnant. So, before 1978, as soon as a woman got pregnant, it was perfectly reasonable for a company just to fire her. And then the Women’s Business Ownership Act only passed in 1988, which was so incredibly recent. There are stories of women who had to find a male cosigner to get credit, of women who were widowed, for example, and whose teenage sons—can you imagine that?—had to be their co-signers because their teenage sons seemed more responsible and more financially reliable than the women themselves.

Robinson

With the recency of certain kinds of progress and as well what we were talking about with the World War II situation, one of the things I didn’t expect to get out of your book is the sort of acute consciousness of the possibility of backsliding, of undoing what has been accomplished. The things that are done to advance equality are fragile. They can go away. They can’t be taken for granted.

Cox

Absolutely. And the obvious example of that is the Dobbs decision. Since 1973, Roe v. Wade had enshrined the constitutional right to an abortion, and it’s gone. I started to delve into the sort of likely longer-term impacts of that decision. Of course, it’s too early to say exactly what the full impact will be economically on women and men in this country, but it’s absolutely fair to say that it is a disastrous thing for female economic empowerment. It is a disastrous thing for certain women from demographic groups, like minorities and younger women. It’s a travesty.

Robinson

And as you’ve shown so compellingly in the book, the fight for economic equality is so closely linked to the fight for reproductive rights. Control over one’s reproduction is a precondition to achieving the kind of economic life that somebody wants to have.

Cox

I think that was actually one of the big surprises that I had when I was doing all the reporting. Of course, I knew that having access to birth control and to reproductive health care was going to be a major factor in economic independence and empowerment, but I don’t think I quite appreciated how radical it was. And that’s, I think, also another reason why I enjoyed reporting the Katharine Dexter McCormick chapter so much. The pill was approved in 1960, and had actually been approved a little while before that to regulate the menstrual cycles of women. So, women could take it, but they couldn’t take it explicitly for the goal of contraception. And in that time period between the pill being approved for regulating menstrual cycles and for contraceptive purposes, suddenly, every woman in the US had problems with regulating their menstrual cycle. So, it was like the worst kept secret in the world. Everyone suddenly wanted to take this pill because contraception was just such a desirable thing at that time. And in many ways, 1960, which was the year that the FDA finally approved the pill for contraceptive purposes, was the beginning of a very promising period of progress, a sort of “rise” part of the book, if you will. Just fascinating.

Robinson

Maybe you could talk about what happened after that period. Because it is true that when you look back at the women’s liberation period from Betty Friedan to the early ’70s, it is this remarkable raising of consciousness and the militant demand for equal rights, and then there again, you have a backsliding. The ERA fails, as you point out, and you discuss the kind of fascinating figure of Phyllis Schlafly: in some ways a model of women’s empowerment who uses her empowerment to advocate the disempowerment of others.

Cox

Absolutely. Again, a fascinating story. The 1970s were extremely formative. There were an awful lot of Supreme Court cases that essentially started to address these imbalances in Social Security benefits, in widowers benefits, and all these kinds of things. And then, of course, 1973, the Row decision, and then the failure of the ERA. But it was really, I think, the period in the 1990s that, I thought, was perhaps one of the most depressing to report on and to write about. In many ways, by 1993, we were seeing women rising through the ranks professionally, leading Fortune 500 companies. As you say, marital rape had finally been outlawed across all 50 states by 1993. Ruth Bader Ginsburg was nominated to the Supreme Court in that year as well. So in many ways, we had all these markers of progress. But what happened really in the 1990s was this emergence of a cultural backlash against female economic empowerment, and not just economic empowerment, but female empowerment in its entirety. This was the dawn of 24 hour news, which I think had the effect of just hyper charging anything that was happening in the cultural mainstream. And ultimately, what we saw was a rise of a highly misogynist culture objectifying women. And then, of course, we have things like the Monica Lewinsky and Anita Hill trials, and all of that just sort of normalized this idea of victimizing women, of basically undermining women’s authority in a very highly public and damaging way.

Robinson

To return to the theme of backsliding, it does strike me that as of right now in this country, Donald Trump is leading Joe Biden in the 2024 polls. Donald Trump is someone who has been convicted in civil court of sexual assault, and then defamation against the woman that he assaulted. I’m certainly not the first to observe that it seems like a few years ago that might have been considered disqualifying. And it doesn’t appear to be, which is very strange and alarming.

Cox

Well, maybe more than a few years ago, because it was the last election cycle when we didn’t collectively seem to deem it a problem that a president had openly and publicly bragged about sexually assaulting women. But I continue to be absolutely shocked and outraged by the fact that a man who has, as you say, credibly all kinds of charges or accusations against him, who’s been credibly accused of sexual assault, who sort of almost carries misogyny as a badge of honor, is deemed the most responsible and appropriate to lead this country. It is just deeply terrifying. And I think what’s even more terrifying is that we used to think of younger generations as perhaps more progressive and less tolerant of behavior like this, but what we’re seeing now is actually the opposite. We actually are seeing among younger generations that sort of behavior is tolerated, and that there’s actually this real kind of entrenched cultural misogyny in a lot of the younger generations.

Robinson

To conclude here, tell us where the frontlines of the battle for gender equality are today. What are the foremost kind of issues and fights that are going to be waged within our lifetimes?

Cox

Well, I certainly think that reproductive rights will continue to dominate that fight predominantly in the US, but I think everywhere. And I think that the issue that is not going to go away either will be the social support system that is entirely lacking. One of the things that I keep coming back to in the book is that if the US had affordable, dependable childcare, I would not have written this book, quite frankly. It’s part of the puzzle that so many other countries have figured out. And yet, somehow, the importance of having dependable, affordable childcare is just not really in the cultural DNA of America. The implication of that is that the job of childcare and of being the fabric that keeps the family and society functioning is the woman’s job. And I think until we address and fix that, progress will be elusive.

Robinson

It’s one of those problems that we’ve come close to solving, and then unsolved during the pandemic, where we actually gave people some aid for childcare and then took it away.

Cox

Right, and during the Second World War, we actually did have facilities in place for children to be in a safe, caring environment during the day while a woman worked in the paid labor market, and my goodness, that was 90 years ago.

Robinson

I think another important reminder is that it doesn’t have to be this way. These are choices that are made. These are policy choices, they can be changed, and it’s within our power to change them. These are not, in fact, natural, immutable hierarchies that are the product of some unchangeable human nature.

Cox

Exactly. But I think culturally, we just have still some way to go. And I think one of the arguments that I make in the book is the reason that we don’t have dependable childcare is that there still is somehow this underlying fundamental belief that if we provide reliable childcare to all it will somehow chip away at these traditional values of the good American family. It’s ludicrous, quite frankly.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.