Yes, Your Child Could Make Modern Art

Art doesn’t need to be the product of special “genius” to be appreciated.

There is, in the Current Affairs library, a rather fun little book called Why Your Five-Year-Old Could Not Have Done That: Modern Art Explained. The author, Susie Hodge, is writing for the type of person who sees a celebrated work of modern art and doesn’t get it, muttering that “my 5-year-old could have done that.”

No, they could not, Hodge says. You may think your 5-year-old could have dripped paint like Jackson Pollock or left their bed unmade like Tracey Emin. But you would be in error. While the work of modern artists can be difficult for the average person to appreciate, this does not make it unsophisticated, and Hodge wants to explain to the general public why works that appear unskilled, ugly, or simplistic have attained renown.

Take one of Gerhard Richter’s “Grey” paintings, which looks like this:

Hodge explains that while the painting itself may be simple enough for a child to produce, Richter’s paintings are “created to investigate feelings of loss and hopelessness, and express hidden truths that Richter believes are exposed in painting by chance.” (Richter himself said that such a piece “makes no statement whatever; it evokes neither feelings nor associations,” though he also said it was “the only way for me to paint concentration camps.”)

A lot of people get frustrated by the acclaim afforded to paintings like this, because they don’t look like the product of real artistic skill. Cultural conservatives tend not to like them. Steven Pinker has written that “modern and postmodern works are intended not to give pleasure but to confirm and confound the theories of a guild of critics and analysts, to épater la bourgeoisie, and to baffle the rubes in Peoria.” Some think modern art is a gigantic hoax, with work so simple that a 5-year-old could have done it passed off as a thing of genius. “Explain what this painting means and why it is good,” a commenter on social media recently demanded. The painting in question was “No. 7” by Mark Rothko, consisting—as most Rothko paintings do—of simple fields of color with soft edges. The viewer appeared baffled, especially at the fact that the painting had sold for $82.5 million in 2021. Responders tried to explain that the painting didn’t necessarily mean anything, that Rothko was trying to create a pure aesthetic experience, that to understand fully requires seeing it in person, etc. But plenty agreed that selling a bunch of meaningless blotches for such an eye-popping sum of money seemed somehow grotesque.

It’s easy to get inside the mind of the haters of modern art. To anyone who doesn’t see the point, the whole enterprise looks like a form of insanity. Marcel Duchamp put a urinal on display, it became perhaps the single most important work of modern art, and a replica of it fetched nearly $2 million at auction back in the ’90s. Andy Warhol, who could seemingly barely draw a cat, painted a cartoon of a soup can and got filthy rich. Ellsworth Kelly put seemingly random simple geometric shapes on a wall, and Ed Ruscha painted words like “OOF,” “OK,” and “SMASH” on canvas or paper. They sell for tens of millions of dollars. There’s Damien Hirst’s shark in formaldehyde, of course. Mike Kelley’s plushies. Jeff Koons’s kitsch. Chris Burden having himself shot with a rifle. A bunch of canvases that are just painted white. On multiple occasions, janitors in art museums have mistakenly thrown out “trash” that was actually intended to be “art” (such as one consisting of empty champagne bottles and confetti, and one made of newspapers and cookies). A banana duct-taped to a wall fetched $120,000. There’s the Mondrian that was accidentally kept hanging upside-down for 75 years, which certainly suggests that its orientation didn’t matter that much. Was Piet Mondrian, then, producing nothing but a bunch of random lines?

I confess, my own first experiences in modern art museums left me confused and upset. There was a highly-regarded museum on my college campus, and when I first stopped by hoping to see things that were beautiful and breathtaking, I was disappointed at exhibits that consisted of things like a lightbulb affixed to the wall, and labeled “Lightbulb,” with a statement explaining the profound meaning of the lightbulb. At the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, I came into a room where the floor was covered with wrapped pieces of candy. It turned out that the pieces of candy, by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, were famous, and they were a statement about AIDS. “Okay,” I thought, but I wasn’t terribly impressed. (I thought at the time that you weren’t supposed to eat the candy, because it was Art, but I later found out that you were supposed to eat the candy, and this was part of the Art.)

I wasn’t much more impressed at The Broad in Los Angeles. Robert Therrien’s “Under The Table” is a giant table and chairs set that you can walk under—and feel like a child again in doing so. That’s cool, I guess. Barbara Kruger’s “Untitled (You are a very special person)” is just the words “You are a very special person” over a picture of a crown. There are always those serious little labels accompanying these things: “1995 / photographic silkscreen on vinyl / 92 3/4 x 126 in. (235.59 x 320.04 cm).” The exact dimensions and materials are treated as very important.

Susie Hodge does her best to explain why my initial reactions to these kinds of works were ill-informed. We shouldn’t, she says, treat “absence of technical skill as a lack of artistic sophistication and ability.” Many of these works are part of an “art of ideas” that evolved after artists stopped seeing good art as art that directly imitates the world. Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism were all met with horror in their day because it wasn’t immediately apparent to the casual viewer why the artist made the choices they made. But must everything be obvious? Those who bristle at Rothko and think Western culture peaked with Caravaggio seem to be rejecting the very possibility of non-representational art. Do they think every artist should be Chuck Close, painting as close to photography as possible to the point where it’s impossible to distinguish between the two?

But Hodge’s book inadvertently gives quite a bit of ground to the haters of modern art. For each work she profiles, Hodge gives a brief explanation as to why a 5-year-old “could not have done that.” And her explanations seem, well, a bit strained. Martin Creed’s “Work No. 227: The Lights Going On And Off” consists of lights going on and off in an empty gallery space. Hodge explains that “a child could switch lights on and off, but Creed was exploring society’s ingrained expectations of art and intentionally provoking reactions of disbelief, anger, surprise, and comedy.” Creed won the prestigious Turner Prize in 2001.

Hodge’s explanation is often some variation on the same thing. A child might be able to make the piece, but a child is not an Artist with Big Ideas, and therefore a child could not make a great piece of Art.

About Piero Manzoni’s “Artist’s Shit” (a series of cans purportedly containing the artist’s shit), Hodge says that while “any five-year-old child could have deposited their own excrement in a tin,” Manzoni “was making several points that few children would be able to appreciate.”

About Lucio Fontana’s “Spatial Concept ‘Waiting’” (a blank canvas slashed with a knife), Hodge says that “the slash of a knife across a canvas looks easily achievable” but “a child would not do it for the same reasons as Fontana” who “aimed to explore underlying notions of space and infinity, as well as the limitations of art and its ultimately perishable nature.”

How about Stephan Huber’s “Works In Wealth III,” which consists of three candelabra in a wheelbarrow? According to Hodge:

“A shiny wheelbarrow piled high with an even shinier chandelier is something that any child could put together with a little effort. However, the fact that the work is situated in a gallery space indicates that the artist was exhibiting it for meaningful reasons not immediately apparent. Indeed, produced in the 1980s and 1990s, it symbolizes the public’s attitude toward capitalism, which decisively triumphed of communism at the time but was also perceived as exploitative by many.”

Likewise, with a chandelier made out of underpants: “Many children would thoroughly enjoy making” a chandelier out of underpants, by the artist’s “reasons went much deeper” and “she chose underpants because they are coverings for parts of the anatomy that are particularly important in terms of birth, privacy, and sexuality.” The same explanation applies to pieces like John Latham’s Still and Chew: Art And Culture (a briefcase containing chewed up bits of a book on art theory) and Jannis Kounellis’s Untitled (12 Horses) (literally just 12 live horses tethered in a gallery). Each time, the explanation is that while, yes, a pile of underpants might seem childish, the Artist was expressing a Big Idea about capitalism, or consumer culture, or sex, or that old classic Calling Into Question The Very Nature Of What Constitutes Art.

Hodge’s core argument, then, is that what looks childish is done with the intent to convey profound ideas, which differentiates it from the work of children, who do not attempt to convey profound ideas. In fact, there’s some empirical support for Hodge’s view in Ellen Winner’s How Art Works. Winner, a psychology professor, decided to run actual experiments to see if ordinary people could differentiate between works by abstract expressionist painters and works by children (and animals). She found that even those who don’t like abstract expressionism can tell the difference between this kind of work and children’s art. So can computers, which Winner says shows that there are meaningful differences and “your kid actually could not have done that.” It is not just that there is more sophisticated intent in the minds of great artists. The artwork itself displays enough signs of that intentionality to make people conscious of the difference. We might say that we can’t tell the difference between art by an elephant and award-winning abstract art, but if you put the two next to each other the differences become obvious.

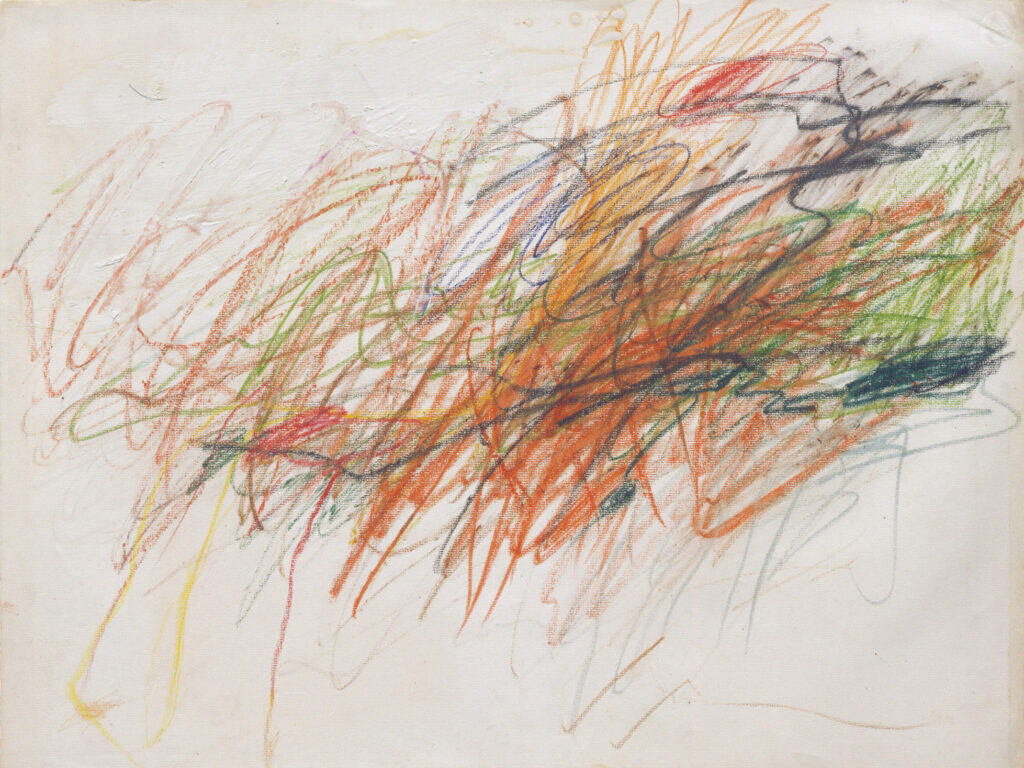

Still, I’m not sure how much Winner’s experiment actually proves. Okay, so if you put my scribbles next to Cy Twombly’s scribbles and told people that one scribble was art and the other (mine) was garbage, most people would probably be able to tell the difference. But Winner also shows that people are discerning the differences by detecting intentionality (i.e., does this look like it was done on purpose?). She found that when you show abstract art that does not look intentional, and a child’s drawing that does, people’s ability to differentiate diminishes.

So has Winner really proved that “your child could not have done that”? Or has she only proved that children tend to be less purposeful in their artworks than actual artists? How significant is it that something “looks like it was done on purpose”? Is that enough to make it sophisticated, valuable, and deep? When I read Hodge’s explanations of the differences between Great Art and childish drawings, so much of it seems to hinge on the fact that the artist meant to express something profound, while the child does not. Usually, however, the thing the artist is trying to express doesn’t seem all that profound to me. (“The Lights Going On and Off” “encourages visitors to think about the room itself,” we are told in The Twenty First Century Art Book. Okay, I thought about it. Can I go home?)

There’s also something implicitly insulting to children themselves in the whole framing. The aggressive insistence that “your 5-year-old could not have done that” assumes that if a typical 5-year-old could have done something, it must not be profound and meaningful art, because that is something adults do. If we prove that a 5-year-old could have done it, we’re proving that it sucks. This assumption is shared by both the critics of modern art (who say a kid could have done it) and the defenders (who say that a kid could not).

I take a different position: I reject the idea that we need to prove Great Artists are superior to children. In fact, the whole exercise seems to me to fetishize individual genius. The idea is that Mark Rothko cannot possibly be doing something that other people could do. He is Rothko, a great genius artist, and to maintain his status we must prove that his fuzzy color fields have some extraordinary property that yours do not.

But what about going in the other direction and arguing that there isn’t anything that makes Ellsworth Kelly’s shapes that much more profound than shapes you might cut out yourself, but that’s okay? If we see ordinary people as having quite remarkable creative potential, it doesn’t make Ellsworth Kelly’s shapes worthless. To show that something isn’t beyond the capabilities of ordinary people only devalues it if you place a low value on what ordinary people can do.

Take Henri Matisse’s very simple late period work, such as his painting of a leaf and his paper cutout of a snail:

I love these, but I have had to overcome my first reaction, which was to search within them for signs of Matisse’s genius. There must be, I thought, some deep brilliance in the particular choices made here. I do think Matisse’s unparalleled eye for color, and his warmth, is clearly on display. But I don’t think we have to come up with some elaborate explanation for why the snail that Matisse made out of construction paper is wildly different and profoundly better than the snail that a child would make out of construction paper, or why his genius is embodied in this simple leaf.

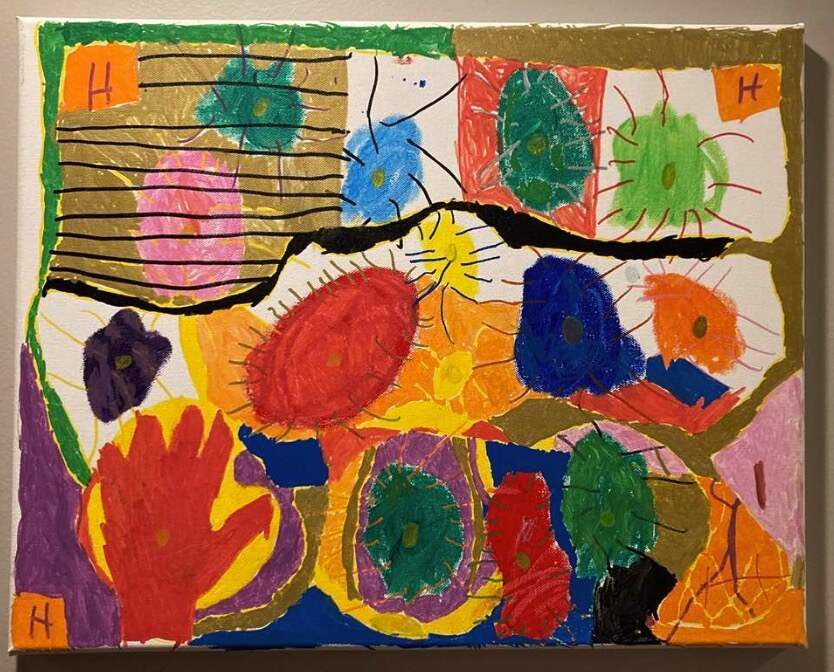

Pablo Picasso supposedly said that it took him a lifetime to learn to paint like a child. I take him seriously there. Instead of insisting that great art could not be done by children, why not appreciate what children do? An acquaintance recently posted a work their 7-year-old nephew did on social media, and I found it completely absorbing. It definitely displays the kind of “intentionality” that Winner says marks the difference between a great abstract work and a childish scrawling, and indeed his parents tell me the child spent many, many hours very carefully and meticulously putting everything in what he felt was the right place:

I would much prefer to have this in my house than a piece by Yves Klein or Cy Twombly, and if that makes me a philistine, so be it.

Still, the fact is, silly as I find a lot of stuff in the modern art museum, I can’t hate it. I liked the big table. I like the underpants chandelier. I like Warhol’s Brillo boxes and Ed Ruscha’s “OOF” and Tracey Emin’s bed, and I find Mark Rothko’s paintings pretty mesmerizing, and I would love to go and see Mondrian’s “Broadway Boogie Woogie.” I used to think that I didn’t like modern art because I’m among those who find a lot of million-dollar splodges unfathomable. But I realized that I don’t hate the splodges at all.

I think what I hate is the pretension that goes along with them, the idea that Jackson Pollock is doing something more than just drizzling paint in interesting ways on a canvas, that he has to be doing something more. Why can’t he just be producing something original and interesting? Why do we need to prove that it’s the work of a Great Man and that he’s doing what the rest of us never could? I don’t actually have a problem with Cy Twombly’s scribbles. In fact, I think they’re kind of cool. My problem is with the idea that these are some kind of special scribbles, that none of the rest of us are capable of scribbling with the exquisite perfection of Twombly.

I also have a problem with the prices. In fact, I think a lot of people’s negative reactions to modern art come from the fact that these works are not just deemed good, they’re deemed ten million dollars good. It’s hard for me to evaluate the “banana taped to a wall” as a work of art, for instance, because I can’t suppress my knowledge that it sold for $120,000. Let’s say it had sold for the price of a banana and a piece of tape (40 cents?). Then what would I have thought of it?

Well, I might still have thought it was pretty dumb. But the point is that a lot of distaste for, say, Damien Hirst’s formaldehyde shark (“The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living”) arises from the fact that it sold for over $8 million. If it hadn’t been wildly overpriced, it might be possible to appreciate it as “nifty” and “cool” rather than seeing it as some pretentious con. The person online who was mystified by Rothko was driven to their position by the ludicrous sales tag. If you could get genuine Rothkos for $3.99 at Walgreens, they might have been less hostile. The high prices contribute to the idea that these works are the product of superhuman genius rather than humble acts of creative expression that provoke novel thoughts and feelings.

I don’t have a problem with modern art, I have a problem with the modern art world, which seems to subscribe to the belief in individual genius, where some people are Great and most of us are not. I don’t have anything against someone setting up an exhibition where the lights go on and off and encouraging visitors to contemplate the room. I don’t think it’s very interesting personally, but I only get upset when it’s treated as something brilliant, worthy of a prize.

Perhaps the concept of “art” is ultimately not very helpful. It’s a very ill-defined term, which has led to endless debates over what “is” or “is not” art, which are entirely irresolvable since the concept has no reality beyond our understanding of it. Duchamp’s urinal kicked off a century of this: Is it art? Is the artist’s shit art? Is a painting of a soup can art? Is a shark in formaldehyde art? Is a sculpture of a balloon dog? Are the incredible painters and cartoonists who do pieces for magazines like this one producing “illustrations” but not Great Art? I had a friend who went to art school and was a brilliant silversmith, but her jewelry was looked down upon because it was “craft” rather than “art.” If she’d claimed it contained Big Ideas about capitalism and perception, then it would have been art. But it was just pretty, so it wasn’t art. There’s a similar scene in the movie Ghost World, where the main character draws a wonderful picture of Don Knotts for her art class. Her art teacher isn’t impressed because the picture has no meaning. “I just like Don Knotts,” she explains. Too bad. Not art. On the other hand, the teacher is hugely impressed by the student who put a tampon in a teacup. She has made Art because it’s a statement about gender roles or something.

I feel we could probably do without the word “art” altogether actually. Do we truly need it? I’m not talking about doing without painting, sculpture, dance, pottery, mosaic, etc. Just doing without the idea that there is some category of these activities called art, and some paintings are not really art. I think we could have a wonderfully creative society where people did all kinds of visually interesting things without ever having to have discussions about what “art” is. So you want to paint a boat with interesting designs? Cool. Is it art? Who cares?

I don’t much care for galleries, either. The solemnity, the bareness, those little placards with the dimensions that make the art seem like a pickled brain in a medical facility or a dinosaur skeleton. The quiet and emptiness does facilitate fixating on, and contemplating, a particular piece, by a particular person. But it always feels so unnatural and clinical to me. At the New Orleans Museum of Art (which is excellent), they had one of Nick Cave’s incredible “Soundsuits” on display a while back. I loved it, but I also felt that something so wild and colorful deserved to be out in the world, moving around, not kept in a gallery like a pinned butterfly. The fun is ruined.

Fact is, there are some things I actually love about modern art. I think of it as a critically important break from the mundanity of much of the contemporary world. A lot of America is just a big strip mall, with the same CVS, the same Starbucks, the same Hardee’s, repeated over and over again, with people talking about the same things. Modern art breaks us out of boredom, it shatters the ordinary and exercises our brain to think in new ways. How dull would life be if every painting were just technically-proficient representational portraits, landscapes, and still lifes? I can appreciate Renaissance art, but I have to admit that the modern era was a massive creative breakthrough, an incredibly liberating period. Picasso’s earliest drawings are incredibly technically skilled—and also much less interesting. It was only when he broke out of the mental straitjacket of traditional rules that he was able to produce things that were dazzlingly unique, like nothing that had ever been seen before.

A big part of the problem with modern art is that the people who like it tend to be snobs who think disliking the things they like is a sign that you’re stupid. I think we need to get rid of the snobbishness, and we can treat some works of modern art as pretentious while unashamedly loving others. I don’t think much of the piece where Marina Abramović sits in a chair for 700 hours (a “revolution in performance art,” apparently), even when the ideas behind it art explained to me. And that’s okay. I don’t have to like it and neither do you. Am I glad there are people doing things like sitting in a chair for 700 hours to see how it makes people feel? Yes, I think the world would be slightly less interesting without Abramović in it.

As I comb through The Twenty First Century Art Book, I see a lot of things that strike me as complete shit. (A pixelated jpeg of the Burj Khalifa, a bunch of cigarette butts in the sand.) And I’m going to maintain that judgment even when I’m told that the artist did this on purpose to express something important. On the other hand, there are modern works I’m completely blown away by, such as the work of Kara Walker, Chris Ofili, El Anatsui, Alfonso A. Ossorio, and Kerry James Marshall. I don’t much like Pollock, though I am impressed by him. And there are other things that I think are not the products of genius, but are nevertheless nifty. I don’t think Jeff Koons’s balloon dogs are very interesting intellectually, but they’re a cool novelty, and I think it’d be cool to come across one in a city.

I am, in my way, a very anti-intellectual appreciator of modern art. I don’t like to theorize about it or even really talk about it; I just like to experience it. I don’t always get it, and sometimes I think it’s contrived. I get why some people think it’s idiotic to put a bunch of candy on the floor as a statement about AIDS. But I enjoyed my time in the room with the candy. More rooms should be filled with candy. It just shouldn’t be done in the name of a thing called Art.

Susie Hodge talks about an art exhibit consisting of a yard filled with tires, which people are encouraged to jump on. She gives her usual spiel: while it’s true that children would love nothing more than to roll tires into a yard and play in them, the artist had lofty ideas in mind when he did this. But I think artists are trying too hard to be adults. Why do we need to do things that a kid couldn’t do? Why do Jackson Pollock’s dribbles and drizzles have to be special serious adult dribbles? So your kid could make some of the things that appear in galleries. So what if they can? Great art doesn’t need to come from singular geniuses. Maybe we can all do it. And we should.