Will AI Enable New Musical Creativity or Undermine Musicians?

On my astonishing and somewhat alarming experiments with music generation software, and what AI technology means for music-making.

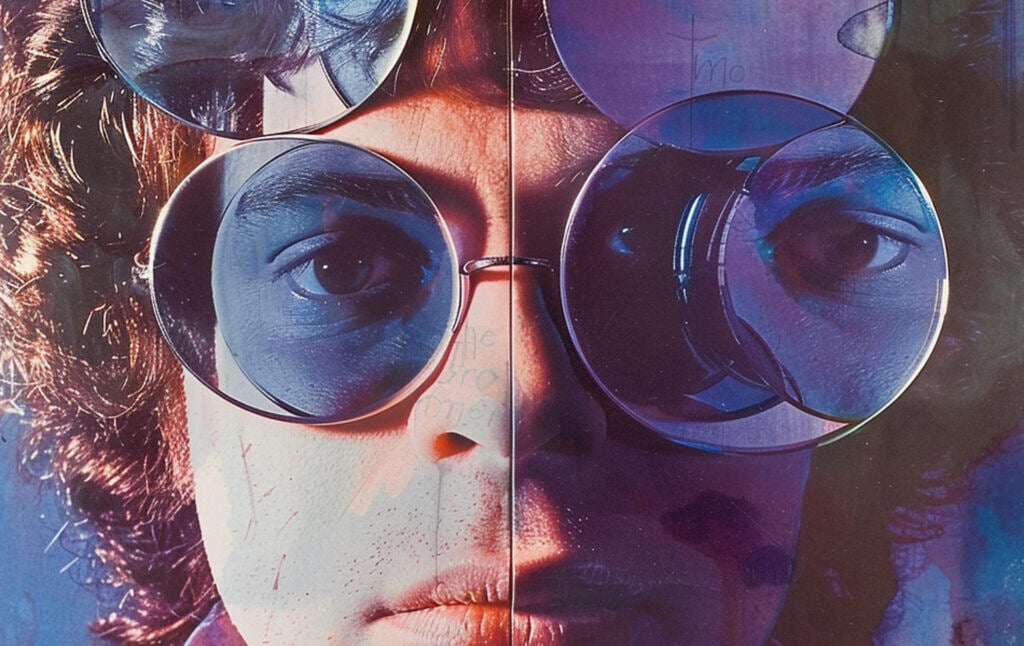

I am now, strictly speaking, a recording artist. I’m on Apple Music, Spotify, and everything. I can’t sing very well, and the only instrument I have ever played is the accordion in middle school, which I was really quite bad at. What I do have, however, is a deep love of music, a whole lot of imagination, and access to the next generation of astonishingly powerful music generation software. And so I produced an album. It’s called The Impostor. You can listen to it for free, in its entirety, on SoundCloud. It might even be a hit. Who knows?

The Impostor is primarily a showcase of what new “AI” music generation technologies can do, although I also tried to make some groovy songs on subjects highly personal to me. (Plus some, like “Slippery Cabbage Time,” that are just goofy). Frankly, I’ve been shocked by the capabilities of the software. I was able to take random notions for songs from my head and turn them, within a few minutes, into fully produced songs. Many of these are quite catchy, the voices and instruments uncannily realistic. Across its 27 tracks, The Impostor incorporates many of my favorite styles, including surf rock, psychedelic pop, reggae, soul, and doo-wop. I had to do a lot of editing and rearranging of the fragments produced by the program, and I rewrote a lot of the auto-generated lyrics and frequently supplied my own, but I didn’t play a note. I was something more like a conductor, arranging everything as I wanted it, with an artificial intelligence software called Suno making the music. In some ways, this is not that far from how other kinds of electronic music are already made. But what’s striking about the songs I made is how little they sound like electronic music—even though they are, just as much if not more so than anything you’d think of as “EDM.”

Even the auto-generated lyrics, though I modified and replaced them frequently, were often impressive. The opening song, “U.S. Foreign Policy Is A Menace To The World,” is a Chomskyan critique of American power. After I said I wanted something that began “From Iraq to Gaza,” the AI gave me: “from Iraq to Gaza, it’s a never-ending fight, leaving destruction [and] pain in its wicked, twisted wake,” which is now in the song. I was most floored by my effort to produce a song on a very specific subject: a soldier traumatized by war who leaves the battlefield and opens an amusement park, only to see constant hallucinations of skeletons appearing on all the rides. The result is haunting and bizarre. It’s called “Amusement Park Full of Skeletons.” (Speaking of things that are full of other things, I also have a two-part song on the album called “New York Is Filled with Rats” that captures my feelings about that city.) It wasn’t the only extremely specific song I did: I have read before about someone who woke up convinced that their entire family had been replaced with identical-looking impostors, and so I did a song about coming home for Christmas and believing your family are strangers, and wondering why they keep telling you they know you and love you. It’s called “Familiar Strangers.”

There are a few themes that run through The Impostor. A lot of it is about artifice, impersonation, image/reality, surfaces/essences, not knowing what’s real and what’s fake. (See the tracks “Irony Poisoning,” “Impostor Boogie,” “The Impostor.”) Another is that Palestine should be free. (See “Endless War Serenade,” “Song For Gaza.”) A third is that while music won’t bring us socialism, it can liberate our souls and provide relief in a troubled, sick world (see “Meow Train”).

I had a hell of a lot of fun producing The Impostor, and as with my other experiments with generative technology, it feels liberating to my creativity. Weirdly, even though the instruments and the voices are generated by a computer, the whole thing feels so personal. The songs incorporate my influences and sensibilities. (I’m not sure many other artists would produce songs with titles like “The Gymnasium Cravat” and “I Like Owls (But They Don’t Like Me).”) Since making the album, I’ve experimented with narrow subgenres of music (like “tuba funk” and “Soviet rockabilly”) and have gotten results vastly more impressive than I expected. It feels amazing and satisfying to be able to create music as someone who loves music but has never before been able to make more than a few discordant ditties on an accordion. I know that many people will find the idea of computer-generated music like this horrifying (“an insult to life itself”), soulless, cliched, and terrible. But I just can’t prevent myself from feeling joy.

Of course, like other generative technologies, including text and image generators, music generation raises deeply important questions about the social effects of new technology. Will musicians be put out of work when it’s easier to make music with machines? Perhaps, but it also might not be dissimilar to what the invention of the player piano did to pianists. Nobody goes to a concert to watch a player piano do its thing, because people are generally quite unimpressed by feats done by machines. (Hardly anyone is impressed by pieces of AI-generated art, even when it’s incredibly intricate and technically proficient.) Musicians are somewhat protected by the fact that people want to hear people make music. But that applies mostly to live performance. Electronic music is a whole different thing, and I do think there are tools now available that can do what some people do. My basic feeling using the tools has been that they can improve, not harm, music, if they are used creatively. But unscrupulous companies will, of course, use them to cut costs, and a Disney director has already tried to replace Hans Zimmer with AI. He didn’t succeed, but the technology is getting better all the time, and my experiments with the new software have convinced me that those who produce, say, radio jingles are probably going to struggle. (I was able to make a radio jingle for my favorite coffee shop and a PSA for COVID vaccines.) We have already seen that the threat of AI to worker livelihoods has become a huge labor issue, with workers having to fight hard to keep companies from deploying generative tools to more efficiently maximize profits at the expense of workers’ livelihoods.

The most critical question with new technologies is not whether they can do interesting or labor-saving things, but who will get the financial benefits. Music generators, like image generators, are clearly trained on a large amount of data from existing musical recordings. While, in the art context, it doesn’t look like U.S. courts are going to conclude that artists have a copyright claim against generative models that use their work in a data set, it’s disturbing that living artists can have their styles programmed into image generators and receive no financial compensation. A fair system would ensure that if an artist’s work is part of what makes an image generator able to produce something, the artist receives some share of the profits.

I’m a socialist, and my approach to ensuring that artists and musicians prosper is not grounded in the enforcement of copyright, because I think art and music should belong to all. I think copyright is a bad way to reward creative people, because it treats creative work as private property rather than the common inheritance of all humanity, and I think we should have a robust culture of sampling and remixing. (I dived into this more on the Current Affairs podcast about the Ed Sheeran/Marvin Gaye lawsuit.) I don’t like the idea that you can copyright a song so that nobody else can record it without your permission. That’s certainly not how rich musical traditions like folk, blues, and jazz were built. I believe that instead of trying to police who takes what art or music from someone else, we should ensure that everybody, whether they create art or not, has a good standard of living and the freedom to pursue their creative interests.

It’s worth distinguishing between critiques of AI-assisted work as culture and critiques of the production side. There’s a difference between arguing that creating music through software will inevitably create bad music and arguing that the software will be used in ways that hurt people materially. Personally, I think we should focus our critiques on the production side, rather than criticizing AI-made things as inherently bad as cultural products. The issue here is that corporations will use AI to ruthlessly cut costs. If music generation is used by musicians and non-musicians to create new, interesting things, then it seems fine. If it’s used to throw people out of their jobs, it is very much not fine. The important thing to ask is who technology serves and how.The Impostor is, in many ways, an elaborate fraud. It’s listed as a “singer-songwriter” album on Apple Music, although it should be “electronic,” because I didn’t sing and I barely wrote the songs. But I did create the songs, and as someone who loves music, I think it’s wonderful to be able to call a song into existence. I don’t know where music generation tech is going, but if it allows for new kinds of experimentation and empowers people to be more creative, perhaps the cultural ramifications of the new technology won’t be as bleak as some people assume. What we all have to agree on is that the technology has to be used for musicians and not against them, and we need to support musicians as they struggle to make sure music technology is used to serve humane ends and not corporate profits.