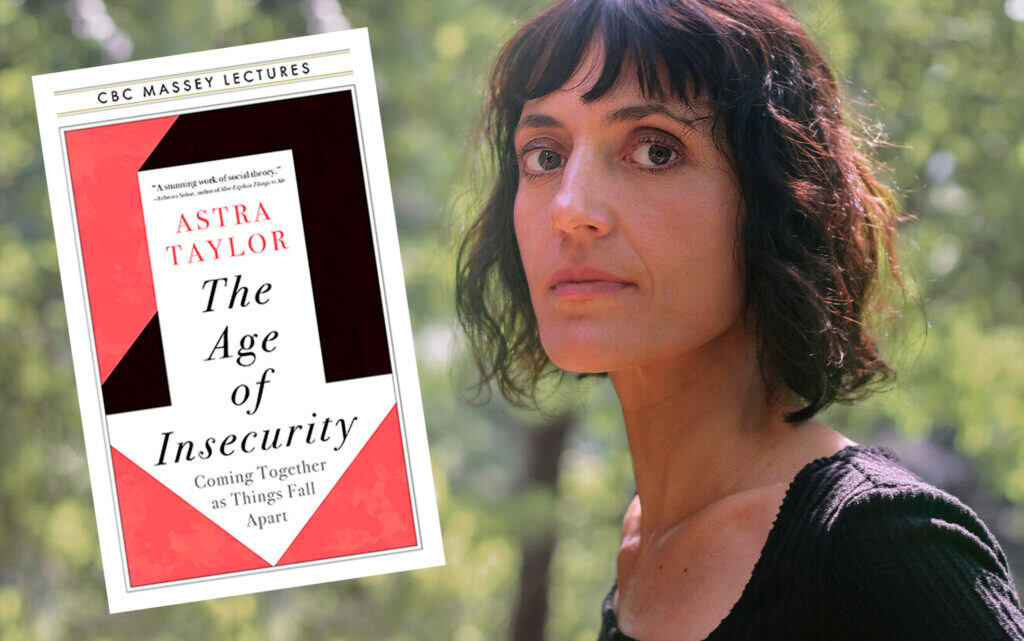

Astra Taylor on What ‘Security’ Really Means

Astra Taylor discusses her book about insecurity, arguing that while the right-wing concept of security involves borders and police, the left-wing version involves creating true security by meeting people’s basic needs.

Astra Taylor is a filmmaker, writer, and activist whose latest book is The Age of Insecurity: Coming Together as Things Fall Apart, based on her CBC Massey Lectures. Today she discusses the themes of her lectures, which are built around the ideas of security and insecurity. What makes us actually “secure”? Security is a word that has right-wing connotations (surveillance cameras, security guards, etc.). But we know that there is another kind of security, the kind promised by programs like Social Security. Astra explains why she, as a longtime activist for debtors, thinks we live in an “age of insecurity” and distinguishes between the kinds of “existential” insecurities we are stuck with and the “manufactured” ones we might be able to get rid of.

Nathan J. Robinson

Your lectures are oriented around this dichotomy between security and insecurity. We’re talking about insecurity, but the word “security” fascinates me because it’s so often associated with the political Right. When you think of security, you think security systems, and you think national security. The people who are most obsessed with security seem to be those who are fearful and paranoid, but you articulate a concept of security that you think the Left ought to embrace. So, tell us what you think security ought to mean when we hear that word.

Astra Taylor

In general, I think we need to struggle over words, and you see this in a lot of my books. So, in my work on democracy, I made a film called What is Democracy? and then wrote a companion book, Democracy May Not Exist, But We’ll Miss It When It’s Gone. Democracy is a tainted word, and I went into that project thinking, we need to throw out this word democracy. I know you and I both like the word socialism, but how many times have you heard somebody say, “we need a new word”? No, we have a word, and what we need to do is imbue it with meaning and struggle to realize it. Certainly, this forthcoming book on solidarity is less a reclaiming of the word but more about thinking it through.

Security is perhaps the most queasy of terms. I came of age under the War on Terror, which was the period of democracy promotion, where the United States under George W. Bush was bringing “democracy” through force to the Middle East. So that was partly what gave me a deep ambivalence towards democracy. But there was big talk of security, as you just pointed out. I really do associate it with Homeland Security and national security. We’re hearing a lot today about the Israeli security state as it wages war on the civilians of Gaza. So, why talk about this? I think there are other meanings to the term that are actually essential to the Left, and we can’t just leave them to the Right.

We want to be secure. We want to know that we’re going to be safe. We want to know that we will be fed. We want to know that we will be housed. We want to know that we won’t be destitute in old age. There’s nothing wrong with that. Why should we let the Right have that concept and that emotional terrain? It’s a powerful emotional terrain, and that’s what I’ve tried to show. The desire for security—and feelings of insecurity—are potent political forces, and the Right is tapping into that every day, saying, you’re afraid to be more afraid, so let us protect you with borders, with police, with the military, with market mechanisms that will actually make you feel worse, with authoritarian political figures who will misdirect your anxieties and vulnerabilities. So, I think there’s a word here, and we need to think about it and reconceptualize it. Security can actually be a beautiful thing.

The last thing I’ll say here is that I love etymology. It’s a recurring theme in a lot of my writing. When you go back to the Latin root of the word security, the word “care” is in there—care is at the heart—and that’s the key. The security we need is the security of caring for each other and building bonds of solidarity, of recognizing our shared vulnerability and insecurities, in finding a kind of collaborative, cooperative, and sustainable form of security that is in direct opposition to this defensive, individualistic, and toxic form of security.

Robinson

So they say, we’ll hole you up in your castle, stockpile as many weapons as you need to feel safe and comfortable, and finally, you will achieve this state of security. But you will never find it that way, and that’s one of the points that you make. Their security is a kind of illusion. You cite one of Franz Kafka’s stories—I haven’t read it, but it’s a story about a mole building his hole, trying to block off every little passageway to finally feel secure, but there keeps being this little noise. You can never achieve that perfect sense of calm and safety that you aspire to through these defensive means. But I think that story is a wonderful analogy for the way that some of us try to seek security in the contemporary United States and Canada.

Taylor

It’s a short story called “The Burrow.” I have long wanted to write about Kafka, and sort of had this research brief that was growing and growing, and I was thinking maybe I could put him in the solidarity book. Kafka is, of course, a brilliant artist, but he worked. He was known in his actual life more as an industrial reformer, and he worked at the state agency, an early example of the nascent welfare state, where he was in charge of workers compensation insurance, which was a new development. He spent so much energy trying to protect workers from all the hazards of the job, and he was one of the many people redefining risk in that period and saying that it’s not the workers’ fault, actually—there are systemic risks in the industrial workplace, and we have to address those instead of just blaming workers as individuals. But he’s also such a great character in that he’s this kind of gentle artist type. He was a vegetarian defying his butcher father, which is something I really like about him, too.

But yes, the story is quite a parable. It’s the story of this creature who seems like he’s a mole, building this burrow, constantly trying to shore up his security and his underground tunnels against some threat, and you don’t know if it’s actually all in the mole’s mind. He’s hoarding his possessions and going around making sure that he has everything that he thinks he needs. It’s this kind of self-destroying prophecy because he’s not really living. He’s just protecting himself. The point there also is not only that this individualistic burrow-bunker mentality is doomed, but that we always need to question our fears. This is one of the complexities of insecurity that I tried to write about throughout the book. When you feel insecure, our emotions can sometimes play tricks on us. And so, we also need to interrogate that and ask: which of our insecurities and our fears are valid, and which are being played upon or exaggerated? We have to discuss emotions—I think that’s really important—but we also have to be critical of them because we can deceive ourselves.

Robinson

I didn’t realize until reading your book that Kafka has a body of work that most people don’t read, which is collected in a book called Franz Kafka: The Office Writings from his time working in the Workmen’s Accident Insurance Institute, which includes such lost classics as, “Measures for Preventing Accidents from Wood-Planing Machines,” and other similar accident prevention reports. I don’t know if it’s a riveting volume, but I’m totally fascinated by it now.

Taylor

He wrote huge amounts of this stuff at his job. There’s this big idea that Kafka had this job that he hated, and he wanted to write, but Kafka understood his job was really important, and in what you cited, “Measures for Preventing Accidents from Wood-Planing Machines”, he invented a new type of saw to protect people’s fingers from lacerations. He saved lives in his work. And so, I just think that makes him all the more interesting. I’m drawn, of course, to figures that wear different hats and have different weird trajectories. He was certainly committed to that work. And, fundamentally, he’s raising questions about insurance and risks, and that at the end of my book I used that to say, insecurity is not just a personal phenomenon, it’s a political one, so we need structural ways of attending to these problems. And Kafka kind of points the way because ultimately, what he argued was that instead of dealing with worker’s comp after the fact, how about if we just make things safer to begin with? Instead of paying a worker because he lost his hand, just make it so he doesn’t lose his hand. It’s a good principle.

Robinson

You say that you’re drawn to people who wear different hats. I’m reminded that the New Yorker recently covered your book and the opening sentences was, “Astra Taylor has a résumé that defies the notion of resume building,” and then goes on to list the many eclectic things that you have done in your life.

Taylor

That was good. I thought, that’s fair.

Robinson

Especially when you see on the list, “cruising around in a Volvo with Cornel West.” But to go back to what you were saying about the kind of fears that so many of us have and how some of them are manufactured, there’s a kind of news story that recurs in the United States that is so tragic. Every year, there are a dozen or so gun owners who accidentally mistake a member of their family for an intruder, shoot them, and often they die. To me, it’s the most horrible possible thing that could happen because it’s entirely your fault, so you have to live the rest of your life with that. These are people who thought they were protecting their family and thought they were making themselves more secure. They thought they were dealing with threats and eliminating all the terrible things in the world, and in the end, they ended up destroying that very security that they sought. That is the most extreme sort of horrible example, but it seems like there are so many ways in which in our quest to eliminate danger [makes things worse]—post-9/11, obviously, the United States’ foreign policy response ended up making the threat of terrorism worse. There are so many ways in which that pursuit of security, which we understand why people want to feel, ends up ruining the very thing that we’re trying to get.

Taylor

Yes. I think that happens in very dramatic ways. I mentioned briefly the War on Terror and why that’s a formative example for me. Growing up in the shadow of the War on Terror reminds me that we always have to ask: security of what, for whom, at what cost? And the point about gun violence is exactly right. There’s just overwhelming evidence that it doesn’t make people safer in the sense that they think it will. But rather, there can be tragedies like you just laid out, or if you are a woman or a child, there’s just a bigger risk that you’re going to be killed by domestic violence with that gun. So, there’s a paradox there, that the things that we think will bring us security undermine it, but I think it just happens in a much more banal way.

And this is why, in the book, I write about the manufacture of insecurity—the way that insecurity is actually a really essential motor for capitalism. It causes us to be on this constant treadmill of pursuing security through various means. We are told the way to find security in old age is by in the stock market, which, of course, is always a volatile prospect. Chances are, even if you screen your investments, that you’re invested in toxic shit that’s bad for workers, bad for the environment, and ultimately bad for you. You’re told to pursue higher education—I know all too well as an organizer with the Debt Collective that debt buries working-class people in unpayable debts that ultimately undermine their security. You’re told to buy a house—even if you manage to hold on to it, you’re helping to raise housing values and push out your neighbors and ultimately create a kind of instability in your community. That’s capitalism, which is why I think we need to be committed to the socialist project of saying, no, let’s provide security as a matter of right—meaning real security that can help people not just survive, but live thriving lives, and to break out of that security paradox.

Robinson

You say the powerful have never wanted the masses to be secured. You explain why that is with examples: the Church telling you that you constantly need to be in fear for your soul and worry about going to hell, to bosses who want you to feel like your job is always on the line—that if you step out of line, your entire livelihood could be taken away from you. There was all this panic early in the pandemic and afterward that workers were becoming too secure, too confident in themselves, and things needed to be reversed. They had to have—you quote Barbara Ehrenreich—the “fear of falling.” All of us have that terrible fear that, even if we’re doing okay right now, it could all go away in a moment. So, it’s not even just about making sure people have a decent paycheck and decent healthcare, because if they’re constantly haunted by that fear that in one moment it could all disappear, then they’re going to constantly feel a sense of crippling insecurity.

Taylor

Yes, one hundred percent. And there’s just a lot of socioeconomic research about this. Insecurity is always forward-looking, so it’s not about absolute deprivation, but about expectation. So, I may feel like I’m okay now, but that things are going to get worse. There’s evidence that people close ranks and are more susceptible to authoritarian politics. They’re just more guarded, and more inclined to think, that bunker—that burrow—is looking pretty good right now. There’s no way I would have written this book without Barbara Ehrenreich’s Fear of Falling, which is one of those books I pored over in my early 20s and thought, what an amazing book of cultural analysis. It’s really entertaining. The subtitle is “The Inner Life of the Middle Class.” It’s essentially a portrait of the professional middle class and the sense that our society is structured so they can’t rest and don’t have enough wealth to pass on to their kids, instead of, here’s your fortune, you’re never have to work again.

Our society is very volatile. As I mentioned, the stock market can crash; you can have a medical emergency and see your family savings be decimated; you can be laid off when your job is outsourced. So, even when people are doing okay, they aren’t wrong to feel insecure under the economic status quo. But you laid it out really well: basically, security is a threat to the powerful because it makes us need them less, and I really do think the debate around the Covid income assistance programs is the most telling.

We saw a radical expansion of the social safety net in the U.S., Canada, and abroad, causing child poverty to plummet. Low-wage workers were finally able to say, maybe I won’t rush into the next horrible abusive job; instead, maybe I’ll wait a week or two and try to negotiate to earn an extra 50 cents or a dollar or more—that would be amazing. That was a threat to the people who run our economy and are in charge of monetary policy. They often use euphemisms, that we need to “bring down prices,” including “the price of labor,” and “restore balance to the economy.” But as I show in the book, Janet Yellen, who is now the Treasury Secretary, appointed by Joe Biden, wrote a memo in the ’90s where she waxed poetic about how useful job insecurity is to bosses. She said—I’m essentially quoting her—insecurity makes workers more desirous of pleasing their employers, less likely to shirk on the job, less likely to quiet quit.

And that was echoed by Alan Greenspan and others. Alan Greenspan made the point that worker insecurity isn’t enough, it actually has to keep ratcheting up to keep having its effect. We live now in the shadow of that ratcheting. So, security absolutely is a threat to the status quo, and that’s part of why I think the Left should reclaim it. Why are we leaving that on the table? The security we’re fighting for should be the security that is a threat to the boss.

Robinson

Just a side note: everyone should read every book Barbara Ehrenreich ever wrote. After her death, I went to write a review of her books, and I was just struck by how, even with the minor books that people haven’t read or heard of, they are always fascinating and profound.

Taylor

I agree. And she also had a PhD in biology. She wrote about everything from joy to midwifery to death. An icon.

Robinson

Your book helped me understand something. Joe Biden is running for reelection, and there’s all these news stories about how even though the Biden economy is doing really well, voters don’t appreciate it. The incomes are going up, unemployment is down, GDP is doing fine. And yet, there is a great sense of dissatisfaction with Joe Biden and the Biden economy. Why is this? Why could this be? I think your book gives us a framework that can help us understand some of this, which is that what you have doesn’t really mean much if you are constantly terrified of losing it. The pandemic was this terrible shock, that the whole world and our circumstances can change overnight. If we see the looming climate disasters in front of us and the threat of escalating global warfare, no wonder people don’t feel great. It’s forward-looking and not just present-looking.

Taylor

Those articles stressed me out. The people writing them, and the people making policy in the Biden administration, need to get it. By just looking at macroeconomic trends like overall job growth and GDP, they’re not breaking it down and looking at how intense inequality still is. There’s still this attitude—it’s not quite “let them eat cake,” but it’s like “we give them some crumbs, and they’re not thrilled about it.” But I think the forward-looking part is really important. And so, I begin the book with a kind of rumination on how we need to think about inequality, the gulf between the haves and the have-nots, which has been a major frame through which progressives on the Left have been thinking about the crisis of democracy and the problems with our economy. But insecurity is important because unlike inequality, which just gives the kind of portrait of this snapshot in time—the rich are this rich and the poor are this poor—insecurity has that affective dimension—the emotional dimension—and, again, that forward-looking dimension. So, it’s not just about deprivation, it’s about expectation.

And as you laid out, people are totally right to be worried right now. They know those gains can slip away. They know that the rent is too damn high and the landlord is going to raise it because that’s what they do, and nobody’s stopping them. They know that the price of groceries is higher than it has been, and they have a sense that prices could probably go up again. It’s just a losing strategy to try to argue with people in this kind of robotic, rational way by saying to look at the macroeconomic data—things are not as bad as you’re thinking—when the Right is talking to people’s emotions and saying, you’ve got fears, and at least we’ll acknowledge them. We won’t give you the solution, and we will tell you to hate those who are even more vulnerable, but at least we are acknowledging your anxiety. So, this discussion just causes me more anxiety because we have to live in the world these idiot Democrats are creating by denying the obvious. This shouldn’t be that hard to get.

Robinson

Yes, it got me thinking that the distribution of security matters just as much as the distribution of actual wealth. The Right comes along and tells you that there are all these terrible things, and we are going to make you safe. I feel like this is something that Biden doesn’t understand: you’ve got to make people feel safe. I certainly feel when I have had a windfall of some money—just a little bit of money in my bank account—well, that’s great. But I know that in this economy, I look at it and think it’s just a matter of time before something comes along that takes all the money. I don’t feel like that is my money. It feels like I’m waiting for the next surprise bill. In fact, just a couple of weeks ago, I got a surprise medical bill from a year ago. I didn’t think they were going to charge me. They charged me. And so, sure enough, a huge part of my money was just gone. You can’t feel secure with anything that you have.

Taylor

We need to decouple security from wealth because that’s what capitalism tells us. We’re going to erode the welfare state, take away your job security, and take away your pension, so that leaves one avenue and one avenue alone, which is to put that money in that bank account—build the burrow up with gold. But you shouldn’t have to be rich to be secure. And actually, there are many ways to provide security for people who lack funds. We don’t want to import everything about Cuba, but they have healthcare, and people are poor. They have health security. I think that has to be at the core of our project, too. We want people to feel safer because they are safer because their basic needs are met.

Robinson

You talk about how some insecurities are because we are human beings, and we are all going to die someday. We can’t eliminate our mortality, and so we can’t eliminate fear and anxiety. There are existential insecurities, as you call it. But there’s also all these manufactured insecurities, these things that make us anxious and afraid that we don’t need. In your book, you cite the example of when your sister worked at a coffee shop and just was casually having a conversation with a customer. It was caught on video, and the boss called and said, don’t talk to the customers! Because everything is a panopticon.

Taylor

It’s happening everywhere. Everywhere is a panopticon. In every workplace, workers are monitored through various apps and services in countless domains, both blue collar and white collar. So, radiologists at the hospital are tracked. Obviously, UPS and FedEx drivers are, and Amazon workers, too. But this bohemian café, full of shabby antiques, was actually the place that was littered with security cameras. And again, what does security mean? Security of what, for whom, and at what cost? This was not about protecting the workers from external threats. This was about protecting the boss’s bottom line by making the workers feel that they were perpetually at risk of losing their jobs, even when they were doing something like just showing a little extra kindness to a regular, which you think would be good for business.

And so, some people have been accustomed to basically being treated like shit. That’s, again, why I think that the idea of security is something we need to reclaim. It should be harder to fire you and to evict you. It should be a whole lot harder to profit from people’s poverty, from people’s pain, and from people’s unexpected medical emergencies. That’s something that shouldn’t be that radical. I am trying to write in that frame.

I spend a lot of my time organizing with the Debt Collective, which means I’m organizing with debtors who have negative net wealth, by definition. But I think middle class people have a lot to gain from a system that provides more material security as a matter of right. And I think given some of the psychological pathologies we’re seeing among the billionaire class, they’d be better off too if we expropriated their wealth and forced them to be more normal.

Robinson

Yes, we should consider those things with security cameras because they are there to generate insecurity in the people being watched.

Taylor

Well, it’s interesting because there’s the word “securitization.”

Robinson

Oh, yes.

Taylor

Securitization means bundling up debts and using them as securities in the Wall Street financial sense. A friend said that we should talk about insecuritization, which is also a process, and is dependent on—as you just pointed out in security cameras—work policies that create job insecurity and the like. That’s really what I wanted to do with this book: demystify the insecurity that’s around us and say that a lot of this is imposed, unnecessary, and has really grotesque goals because it’s there to enrich the already powerful. Let’s denaturalize it.

Robinson

I mentioned that you distinguish between the manufactured insecurities and the existential insecurities. One could hear what we’ve been saying and think that the goal then is to blast through the propagandistic false notions of security and achieve real, meaningful security and end the insecurity. This is not quite how you put it. Interestingly, you do say we have to embrace the fact that we are inherently insecure beings. Could you comment on the insecurity that you feel we are always stuck with and have to reconcile ourselves to, versus the kind that we can mitigate or eliminate?

Taylor

We wouldn’t need security if we weren’t insecure. We wouldn’t need social systems that provide care if we weren’t beings in need of care. In the book, what I call existential insecurity, which is the human condition, is the kind of insecurity that all kinds of philosophers have talked about—the fact that we’re going to die, that we’re fragile. It’s a kind of insecurity that feminists and disability activists have talked about, the fact that we all need care throughout our lives. None of us are autonomous agents. There is no such thing as the self-made individual. And that existential insecurity, I think, is difficult, and we have a range of reactions to it. I think some people really flee from that. They don’t want to admit their vulnerabilities and are encouraged to deny them.

But fundamentally, I think an acknowledgement of our insecurities is key to devising the more collaborative, communal, sustainable, democratic forms of security I think we should be aiming for. I want to see social security based on the recognition that we’re interdependent, that accidents happen, that we aren’t in total control, that we age and get sick. Shit happens, so let’s figure out ways to deal with it together. So yes, I contrast existential insecurity with what I call manufactured insecurity. I am also trying to provide just a slightly different lens on capitalism. We understand capitalism as a system in which capital accumulates and wealth and power accumulate. Capital is a relentless force, and that’s certainly the case. But I think insecurity is actually a core product of capitalism as well, because you don’t have a proletariat—you don’t have a people who have nothing to sell but their labor—unless they are insecure and severed from other forms of subsistence and livelihood. We see that when we look back on the enclosure movement and the transition from feudalism to capitalism. People had to be separated from land and livelihood to be turned into the working classes, as we now know it. And so insecurity is not just an unfortunate byproduct of our economic system, but actually a really core attribute of it.

Manufactured insecurity can be mitigated, and I think that we should do that. And then maybe in our socialist paradise of material security, could actually really have a bunch of philosophical discussions about what it means to be existentially insecure.

Robinson

You’ve mentioned that on the production side, workers are made to feel insecure, but you also point out another form of manufactured insecurity is on the consumption side. You say that satisfied customers are not profitable. No advertising department ever tells us we’re okay. So, we are, in addition to the risk of being fired, also being bombarded with messages constantly that say that we need to buy more to be happy.

Taylor

It’s almost a banal point that I feel like we don’t talk about enough. I rail against advertising in everything I’ve written, going back to The People’s Platform, which is about the political economy of the internet. So many pathologies of social media are driven by the fact that the people running them are advertisers and marketing departments. We’ve given away our whole communications apparatus to the field of advertising, which, by definition, is an industry of misinformation. So, it’s no wonder there’s all this bullshit being promulgated in those spaces. Huge amounts of money are spent on advertising because it works, and it does keep the treadmill of consumption going. And most of it does assault our self-esteem, and has, I think, really pernicious consequences. It’s just a huge waste of money and a huge waste of human creativity. That money could be better spent. And so, I will continue to rail against it like an angry teenager until the end of time. But I think it’s one of the prime examples and people might not really want to face it, but we’re subjected to it all the time, and it certainly has emotional and social consequences. And so, I think it is important to denaturalize advertising, too. This is a huge industry based on manufacturing insecurity. It’s not good for us, and it’s not good for the planet.

Robinson

It’s weird. I feel like the Left in the ‘90s had plenty of critiques of advertising, like with Naomi Klein’s No Logo and stuff, and then I feel like the Left moved away from this and towards, understandably, talking about workers and about how things are produced. But it’s still the case that every advertisement assumes you can be made to feel like you need to alter what you already have and that you would be better off if you handed your money over to someone else.

Taylor

I think the Left has gotten better at going beyond consumerist politics alone, which became almost an aesthetic and not politics. But there’s still something there. Advertising could be subjected to strong regulations from the state. We could also undermine the planned obsolescence advertising encourages by saying, no, everyone has the right to repair things, things have to be made to last with good union jobs.

Robinson

I think there’s fairly strong empirical evidence that it’s connected to the rise in teen suicides. It’s not just economic.

Taylor

Absolutely. I think it’s really doing a number on younger folks, without a doubt. It has certainly reached crisis levels.

Robinson

So, one of the things we do on the Left, and that you do so well in this book and in your other work, is to say that things don’t have to be this way and could be different than they are. These are not natural features. They’re not immutable. They’re not handed down to us from above. We can achieve a world of real and meaningful security apart from the existential insecurities that we may never get rid of.

And you’ve done that so well over the past decade with debt, with changing and really succeeding, actually. You and the Debt Collective and the other activists coming out of Occupy have succeeded in changing the discourse around debt. As David Graeber wrote, there’s this sense of debt as a natural moral obligation that you couldn’t get rid of. But no, we are the ones who decide whether we think that “your debts must be paid” is a natural feature of the world. So, that’s an example of how I do think people’s thinking can change, and the policies can change accordingly.

Taylor

People’s thinking does change. People’s thinking has changed over the course of my lifetime. If you’ve read any history, you think, wow, they really thought differently than we do today. The world is changeable. We can reorganize society. We can do this better and a little kinder, gentler, a little more sustainably. And I think this is a great example because we’re a really small group, and we were not veteran organizers. None of us had very much experience, if at all. We were artists; I was making films about philosophy. What we did have, though, was a commitment to closing the gap between what we were doing and our values. We had a kind of playful spirit too of, let’s just try this—let’s try this crazy idea of organizing the world’s first debt strike to see if it works, to see if we can get any traction. So, for me, I just think what we need is more organizing and more people stepping up to try to change things.

Books are great. I think books and magazines and podcasts are part of the process of changing the narrative and getting people to think differently. But ultimately, this is a power struggle, and we need people to organize and be as rigorous and ruthless as the right-wing opposition, which is a tall fucking order at this moment. We all have got to step up to the plate.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.