The Old Left Renaissance of the “New Masses” Magazine

A dive into the archives of the New Masses (1926-1948) shows a left that tried to forge a new culture. Their successes and ultimate failure offer lessons for our own time.

If you have some spare time for intellectual meandering, and you like curious old things as I do, take some time to open up the archives of New Masses magazine (1926-1948). They are all available online in beautiful high-resolution scans. (A Brooklyn doctor named Martin H. Goodman spent years scanning and uploading every page and has written an essay about the process, which will make you appreciate the craftsmanship of a good high-res scan.) New Masses was a Marxist monthly that followed on from The Masses (1911-1917), which had been suppressed by the United States government during World War I, and The Liberator (1918-1924). It was an extraordinary little magazine, without parallel in our own time.

New Masses was launched with an explicitly cultural mission. Michael Gold, the Communist author of the novel Jews Without Money, who served as a founding editor, had dreamed of a magazine that would experiment in “develop[ing] revolutionary artists—poets, fictioneers, and draughtsmen.” It would finally be a place “where a fiction story with a strong revolutionary or workingclass implication [sic]” could be printed, a “bright, artistic, brilliant magazine that would captivate the imagination of the younger generation and rally them around something real.”

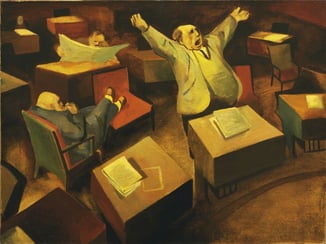

New Masses published some of the greatest writers of its time over the course of its run, including William Carlos Williams, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Dorothy Parker, Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, and Ernest Hemingway. It published Abel Meeropol’s poem “Strange Fruit,” famously adapted by Billie Holiday. Flicking through the archives is a hell of a lot of fun. New Masses issues overflow with satirical cartoons of fat capitalists in top hats smoking cigars and down-and-out workers getting kicked around. The press, the clergy, and the schools are all savagely lampooned. The New Masses take on government is encapsulated in William Gropper’s illustration “The Senate,” which depicts portly, balding men sitting around uselessly or declaiming to nobody:

The New Masses followed the line of the Communist Party, though it was not formally affiliated with it. But it had a sense of humor and play. Gold had a philosophy similar to the famous “revolution with dancing” line often attributed to Emma Goldman. He said:

Attack the filthy, the bloodstained luxuries of the rich all you want to, but don’t moralize against the poor little jug of wine and hopeful song of the worker.… The little pleasure I get out of this wretched world helps me to live and fight. I love humor, joy, and happy people. I love big groups at play, and friends sitting around a table, talking, smoking, and laughing. I love song and athletics and a lot of other things. I wish the world were all play and everybody happy and creative as children. That is Communism; the communism of the future.

For the New Masses crowd, art was an essential part of the revolution. The early editors were aesthetes who had been impressed by Upton Sinclair’s book Mammonart, which argued that most of history’s great writers had been propagandists for the rich and powerful. New Masses contributors sought to create proletarian art that would show the world as socialists saw it.

New Masses issues differ from today’s socialist publications (including this one) in being full of poetry. Some of that poetry is by Langston Hughes, and therefore quite good. Some of it is quite bad, as today one would expect from explicitly Marxist verse. A representative example is John Beecher’s “Annual Report to the Stockholders” (1933):

he fell off his crane

and his head hit the steel floor and broke like an egg

he lived a couple of hours with his brains bubbling out

and then he died

and the safety clerk made out a report saying

it was carelessness

and the craneman should have known better

from twenty years experience

than not to watch his step

and slip in some grease on top of his crane

and then the safety clerk told the superintendent

he’d ought to fix that guardrail

[…]

he shouldn’t have loaded and wheeled

a thousand pounds of manganese

before the cut in his belly was healed

but he had to pay his hospital bill

and he had to eat

he thought he had to eat

but he found out

he was wrong

[…]

the stopper-maker

puts a sleeve brick on an iron rod

and then a dab of mortar

and then another sleeve brick

and another dab of mortar

and when he has put fourteen sleeve bricks on

and fourteen dabs of mortar

and fitted on the head

he picks up another rod

and makes another stopper

Another, “Factories,” by Alfred Kreymborg:

Buried in one-eyed dungeons where the walls

Stare out on other walls through window panes,

A grinding mechanism squats and chains

Each arm and leg to slavish rituals,

The while monotonous privation hauls

Dark bodies to and fro down prison lanes

Where no soft light nor open door remains

To proffer freedom from such funerals.

The eye that peers from out each socket there

Reflects a roving madman in a cave

Striving and straining to burst the stony shell:

The look makes every cell begin to glare,

The very walls to shudder and to rave,

As each grim puppet earns his bread in hell.

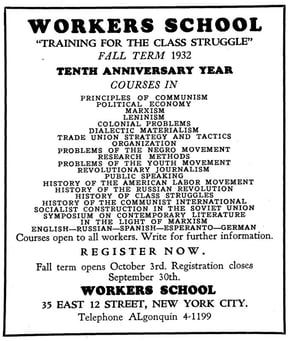

Bleak! And sadly some pretty lasting commentary on the cost of healthcare and the misery of a windowless workplace. Like this stuff or don’t, but I find myself impressed by the New Masses’ attempt to create leftist culture, not just to produce leftist economic analysis and political strategy. Its pages contain reviews of plays, art exhibits, and novels. In its margins are advertisements for lectures on Cervantes, Shakespeare, Goethe, and Balzac and biographies of Lincoln and Poe. The anticipated reader of the New Masses is a dockworker who enjoys ballet and jazz. An issue would contain: short stories about proletarian lives, critiques of American society and culture, coverage of world events (especially in the Soviet Union), literary reviews, cartoons, labor news, debates on leftist strategy, and theater criticism. The language was often salty. Gold’s essay “Gertrude Stein: A Literary Idiot” said that Stein’s novels “resemble the monotonous gibberings of paranoiacs in the private wards of asylums” but “only [reflect] the madness of the whole system of capitalist values” and are “part of the signs of doom that are written largely everywhere on the walls of bourgeois society.” Gold called Marcel Proust the “master-masturbator of bourgeois literature,” the “worst example and the best of what we do not want to do.” It was often dogmatic and unfair. But it was fun, and it’s quite satisfying to read a scathing New Masses book review at a time when the New York Times book review hesitates to say a negative word about any volume it covers.

The New Masses adopted the presumption that art and intellectual subjects should not be considered bourgeois and should be presented for a working-class audience. But they were not “highbrow.” The introduction to one piece runs:

James “Slim” Martin was for years a wandering migratory worker, a harvest hand, lumber jack, and member of the I.W.W. Then for thirteen years he was a structural iron worker, and helped build many a New York skyscraper. Recently he branched off into acting, and played in “Outside Looking In,” at the Greenwich Village theatre, and in Eugene O’Neill’s proletarian dramas. Now Slim Martin has taken to writing, after much urging by the editors of the New Masses. This is his first composition. It tells of the life and feelings of the man who walks steel beams hundreds of yards into the sky. This is a specimen of the kind of worker’s art the New Masses is mining for. Is there more of it in the country? Sit down, you bricklayers, miners, dishwashers, clothing workers, harvest hands, cooks, brakemen, and stone-cutters: wrestle with pen and paper and send us in the results—however bad they seem to you. Write us the truth—it is more interesting than most fiction.

Another solicitation for submissions, written by Gold, ran as follows:

WE WANT TO PRINT:

Confessions—diaries—documents

The concrete—

Letters from hoboes, peddlers, small town atheists, unfrocked clergymen and schoolteachers—

Revelations by rebel chambermaids and nightclub waiters—

The sobs of driven stenographers

The poetry of steel workers—

The wrath of miners—the laughter of sailors—

Strike stories, prison stories, work stories—

Stories by Communist, I.W.W. and other revolutionary workers

Hell, I’d buy a magazine with all that in it.

In fact, as a leftist magazine editor working nearly 100 years after the first New Masses came out, I find much in their pages endearingly relatable, especially their constant schemes to find new subscribers. (One issue offers a free picture of Lenin with every new subscription!) I even think Current Affairs should write up the kind of appeal they published for people to hassle newsstand proprietors:

After you have secured your copy of this issue, stop at every stand on the way home and ask the news dealer if he carries it. If not, why not? If he has it tucked under the counter, get him to put it out where people can see it. Tell him people are interested in the NEW MASSES—it’s the truth. Tell him some of the facts just cited about our steadily increasing sales…. If he’s a good business man he will want to carry it.

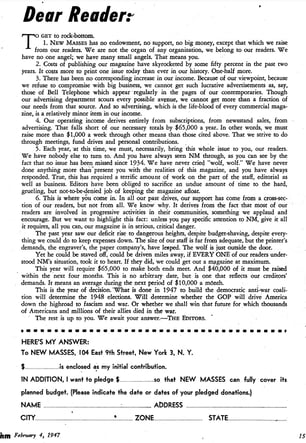

At one point, the editors announced that they were skipping an issue, and extending everybody’s subscriptions, in order to catch up on their publishing schedule. It’s a trick we had to pull here at Current Affairs a couple of times. (The Nov.-Dec. 2016 issue was so late that we just called it the Jan.-Feb. 2017 issue.) Their desperate appeals for funds toward the end are particularly unnerving to an editor struggling to keep a magazine afloat himself:

The magazine folded shortly afterward.

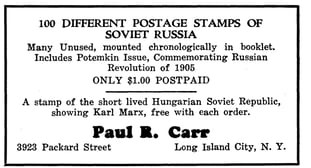

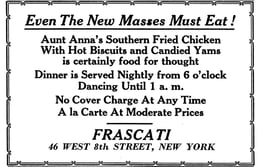

The ads in New Masses are a truly amusing time capsule of bygone socialism. They were essentially ordinary classifieds with a labor twist, with promotional quotes like:

- “To those who hate Bourgeois fiction this book will be a joy! It is a beautiful working class love story.”

- “Wage Slaves! Do you want a real vacation?? … We have organized a camp in the Adirondacks limited to 30 people at a time for $25 a week. Write A.L.H. ℅ New Masses.”

- “The New LENIN Head — FOR WALL MOUNTING (Ivory or Bronze Finish) On display and for sale now in the W O R K E R S B O O K S T O R E / 50 E. 13th St. — New York City.”

- “JOHN’S RESTAURANT — Specialty: Italian Dishes — A place with atmosphere where all radicals meet.”

Some typical New Masses ads:

I can’t help but be charmed by some of the announcements to be found:

- “The Rebel Players of Los Angeles will present their second production, Friday and Saturday March 6th and 7th. The play is Paul Sifton’s The Belt, a play showing the exploitation and speedup of workers at the belt of an American automobile factory. Every worker will find a common interest with the workers at the belt.”

- Whatever you may be planning for Friday evening, January 5th—cancel it now! For on that evening we are celebrating, with fitting ceremonies, a truly cosmic event—the birth of the weekly New Masses—and you’ll want to be there.…It will be a night of exciting fun—constructive dissipation—epic mirth and gaiety! To ensure your complete enjoyment, the geniuses, wits, and talents of the John Reed Club, Theater of Action, New Duncan Dancers, Workers Music League, the Pen and Hammer, and Film and Photo League are collaborating upon a program that is guaranteed to out-do all previous efforts. There will be inspiring music, malevolently satirical sketches, dancers who are terpsichorean marvels, and poetry readings by the one and only Alfred Kreymbourg.

I find myself dearly wishing to travel back a century and attend one of its “proletarian costume balls,” to watch the “red marionettes” perform and see the latest play about the workers’ experience. Cheesy and ideological it may have been, but it is difficult not to be enchanted by the sincere enthusiasm for creating a vibrant pro-worker culture.

The trouble was the Soviet Union. Though the magazine did not take direction from the Community Party, its editorial line was ultimately Stalinist, which casts a pall over the whole enterprise. There are all kinds of ads in the margins for everything from discount trips to the Soviet Union (see the Workers’ State being built!) to Soviet postcards. The magazine’s writers defended the Moscow Trials and the Hitler-Stalin Pact, which tore apart its readership and contributed to its ultimate doom. Michael Gold had a ludicrously romantic and naive view of the U.S.S.R. “It’s a great new amazing place, everything beginning, life young and hopeful and strong.” He did not hesitate to denounce leftists who became critical of Communism.

Looking back, there is something tragic about these poor romantics who thought that somewhere across the ocean, a workers’ utopia was being built. They were so eager to believe that the Soviet myth was true. Classified ads in the magazine offered private Russian lessons. Music stores promoted the records of Soviet composers. Subscriptions to the Moscow News were offered, promising readers answers to their most pressing questions such as “How is the USSR conquering drought?” “What is the position of Shakespeare in the Soviet Union?” and “What is Lysenko’s method of growing potatoes despite heat, wheat despite cold?” You can see why it was hard for them to let go of the myth as revelations piled up about Stalin’s brutality. One can see them as apologists for an evil regime, or as naive people whose idealism can be respected even if they were ultimately committed to a dangerous delusion.

The pro-Soviet orientation of the New Masses makes it difficult to long for anything of the kind to appear in our own time. But I keep returning to their love of culture, their desire to couple economic revolution with artistic revolution. This was a magazine that would sometimes give you a picture of Lenin with a subscription, but another offer was for a discount book of prints by Goya, which the magazine promised would help the reader understand the true nature of war. I can’t help but feel as if our own left has done a good job with political and economic criticism but has simply not risen to the challenge of creating its own counterculture. The New Masses helps us see what that would look like and where we fall short. We need Jacobin to start running more art criticism and writing on sculpture, photography, and dance. I suppose we also need to start taking poetry more seriously, though I have had a strict “no poetry” rule for Current Affairs since Volume 1, Issue 1. (I have only bent this rule once, for William Ehrhart, because his poems are so good and so accessible that I cannot imagine a reader finding them alienating or pretentious.)

The 1930s communists of the New Masses weren’t the only ones who tried to fuse art and revolution. The New Left of the 1960s was both cultural and political, too, with radically experimental music and visual art being central to these “revolutionary” times. I am not sure what a “cultural left” of 2023 would be like, but I know we need one. It is not enough to develop left critiques of production and distribution. We must also think about how to express socialist values through painting and song without being didactic and boring. A great deal of the “proletarian realism” in the New Masses is dreadful, but some of it succeeds at its intended goal of giving powerful artistic expression to the socialist worldview. I hope the painters, dancers, filmmakers, and poets of our own time will look through old copies of the New Masses and think about how we can create our own fresh new challenges to “bourgeois” art.