The Wisdom of Edward Said Has Never Been More Relevant ❧ Current Affairs

The late Palestinian American public intellectual brought moral clarity to the Israel-Palestine conflict, arguing that once the injustice to Palestinians was recognized and ended, peaceful coexistence would finally be possible.

“[D]iscussion of the Arab world in general, and of the Palestinians in particular, is so confused and unfairly slanted in the West that a great effort has to be made to see things as, for better or worse, they actually are for Palestinians and for Arabs.” — Edward Said, The Question of Palestine

“One day you’ll wake up and ask ‘What the fuck am I doing?’” — Edward Said, addressing the Israeli public

Edward Said constantly found himself misunderstood and misrepresented, in part because his real beliefs were often nuanced and novel. The late Palestinian American literature professor and public intellectual is best known for his book Orientalism, a foundational text in postcolonial studies that exposed the persistence of reductive, demeaning stereotypes about the “Orient.” Orientalist scholarship was “that ludicrously inept academic and jargon-ridden school for which such ideological fictions as ‘Islamic (or Arab) rage’ or ‘the Arab mind’ are the stock-in-trade,” concepts that are sadly still in use.

But Said came to lament some of the influence his critique had had. “One of the negative consequences” of the book’s success, he said, is that things got to the point where “if you want to insult someone, you call him ‘Orientalist.’” Said was taken as having implied that all Western scholarship about Arabs and Muslims was racist, or even that Western culture was irredeemably suffused with imperialist ideology. The right-wing commentator Douglas Murray, for instance, associates Said with the belief “that every aspect of the West—even or especially its intellectual and cultural curiosity—is to be not just condemned but derided.”

It’s extraordinary that anyone could think Said believed this, and it shows just how far the public image of Said has departed from the reality of the man’s work and beliefs. Said was a lover of classical music and 19th-century European novels, an aesthete and cosmopolitan who grew up in Cairo and Jerusalem reading Shakespeare. Said’s intellectual project was in part about demolishing fixed, lazy ideas of singular “Western” versus “non-Western” cultures. As a secular Palestinian raised mostly in Egypt by Christian parents with ties to the U.S., he never fit into a box himself, as he recalls in his memoir, Out of Place:

“I have retained this unsettled sense of many identities—mostly in conflict with each other—all of my life, together with an acute memory of the despairing feeling that I wish we could have been all-Arab, or all-European and American, or all–Orthodox Christian, or all-Muslim, or all-Egyptian, and so on. I found I had two alternatives with which to counter what in effect was the process of challenge, recognition, and exposure, questions and remarks like “What are you?”; “But Said is an Arab name”; “You’re American?”; “You’re American without an American name, and you’ve never been to America”; “You don’t look American!”; “How come you were born in Jerusalem and you live here?”; “You’re an Arab after all, but what kind are you? A Protestant?”

People tried to make sense of Said with the reductive categories that he spent his life exposing as ridiculous. He once recalled that an acquaintance came to visit him at his home just to “see the way you lived,” because she was astonished that a Palestinian could live with a piano and a library of classic literature. She must have found it, he said, a “rather peculiar pleasure to watch somebody who is supposedly a terrorist carrying on in a fairly civilized way.” “Palestinian” was virtually synonymous with “terrorist” to some, and so racists (of the Murray type) could not process the idea of a proud Palestinian who was literate, urbane, and did not “hate” the West but nevertheless remained staunchly critical of Zionism and its effects on his people. Because Said did not fit into people’s preconceptions, he was assumed to believe things he didn’t. For instance, he once said, “I’m considered a great defender of Islam, which is, of course, nonsense. I’m really quite atheistic.”

But secularist and classicist that he was, Said did not mince words when it came to the injustice perpetrated against Palestinians by the State of Israel, he and devoted much of his life to trying to demonstrate the basic facts of the conflict, rooted in the original dispossession of Palestinians (including Said’s own family) in 1948. Said tried to break down the “enormous walls of denial that are part of the very fabric of Israeli life to this day,” trying to open people’s eyes to the fact than in Palestine, “there is a guilty side and there are victims” and “the original distortion in the lives of the Palestinians was introduced by Zionist intervention.” The “fundamental problem,” he said, “began in 1948, when as a people we were driven off the land, lost the entire land of Palestine and have remained refugees or second-class citizens ever since.” Said demanded that discussion of the conflict begin with this basic fact:

“We were the people dislodged from the land. We were the indigenous inhabitants who were thrown out to make way for a Jewish state. We are, in fact, victims of the victims.”

Said was frustrated that so few Israelis recognized what their country had done, the fact that it was built on dispossession and sustained through occupation:

“My general impression is that for most Israelis, their country is invisible. Being in it means a certain blindness or inability to see what it is and what has been happening to it and, just as remarkably, an unwillingness to understand what it has meant for others in the world and especially in the Middle East. ”

This did not mean that he was unsympathetic to the original justifications for Zionism; in fact, he described the conflict as a kind of epic historical tragedy (he even used the word “symphony”) in which victims become victimizers, but he demanded an acknowledgment that “in establishing a state for themselves for perfectly understandable reasons, they destroyed the society of another people.” Instead, “we are thought of as kind of nasty people who are doing damage to the Israelis”—with Palestinian violence against Israelis treated as proof of naturally terroristic inclinations—“whereas the fact is the opposite is true”: that the “vastly, vastly greater amount of violence wreaked upon us by Israel” goes ignored or is justified as “self-defense.”

“For the Israelis, there’s always this tendency to think of us as aliens and therefore the fewer of us around the better, and the best are those you don’t see at all….What’s so extraordinary is that what the Israelis are now doing on the West Bank and Gaza is really repeating the experience of apartheid and what the United States did to the Native Americans. Put them in reservations or just exterminate them, which the Israelis haven’t done, but put them as far aways as possible, then the problem will go away.”

Said argued that Israel was in the grip of a delusion about itself and in denial about what it had done to Palestinians:

“[I]n some ways, it is true that Israel’s early history as a pioneering new state was that of a utopian cult, sustained by people much of whose energy was in shutting out their surroundings while they lived the fantasy of a heroic and pure enterprise. How damaging and how tragic this collective delusion has been is more evident with the passing of each day.…How long will the awakening take, and how much more pain will have to be felt, before the opening of eyes is fully accomplished?”

Israel could see Palestinian crimes against Israelis, but could not see its own actions through the eyes of the dispossessed and occupied:

“But what I have found most puzzling is the extent to which so many Israelis seem to have been disappointed and angered by the Al-Aqsa Intifada [the Second Intifada, or major uprising against occupation, from 2000-2005], as if the unceasing rate of settlement activity, the frequent closures, the expropriations, the thousands of humiliations, punishments, and arbitrary difficulties created for Palestinians by Israelis while the two were supposed to be negotiating a peace with each other were all negligible, as if Israel’s magnanimity in “allowing” little bits of Palestinian autonomy were enough to wipe the slate clean and should have made the entire people grateful to Israel for its concessions. Rather than trying to connect the Israeli policy of military occupation with the intifada as cause and effect, many Israelis now seem to want [Ariel] Sharon to take over and, as one of them said to a journalist, ‘deal with the Arabs,’ as if ‘the Arabs’ were so many flies or a swarm of annoying bees.”

The result, he said, was two totally irreconcilable narratives of what the conflict consisted of, with the “almost total opposition between the mainstream Israeli and Palestinian points of view” making rational discussion nearly impossible:

“We were dispossessed and uprooted in 1948, they think they won independence justly. We recall that the land we left and the territories we are trying to liberate from military occupation are all part of our national patrimony; they think it is theirs by biblical fiat and diasporic affiliation. Today by any conceivable standards we are the victims of the violence; they think they are. There is simply no agreed-upon common ground, no common narrative, no possible area for genuine reconciliation. Our claims exclude each other. Even the notion of a common life shared (unwillingly it is true) in the same small piece of land is unthinkable. Both peoples think of separation, perhaps even of isolating and forgetting the other.”

But Said was not hopeless about the possibility for a just resolution to the conflict. In fact, he maintained a belief that Israelis and Palestinians could one day live together in a single binational state. The idea of a “two state solution” came to seem not only impossible to him, but revolting to his cosmopolitan, anti-nationalist convictions, which pointed to the necessity of finding ways to live together, rather than creating two separate entities:

“The idea of separation is an idea that I’m just sort of terminally opposed to, just as I’m opposed to most forms of nationalism, just as I’m opposed to secession, to isolation, to separatism of one sort of another. The idea that people who are living together—this happened, for example in Lebanon—should suddenly split apart and say Christians should live here and Muslims there and Jews there and that sort of thing is, I think, just barbaric, unacceptable.”

He believed that Jews and Palestinians had been “thrown together” by history and needed to accept that their destinies were now intertwined:

“Our history as Palestinians today is so inextricably bound up with that of Jews that the whole idea of separation, which is what the peace process is all about—to have a separate Palestinian thing and a separate Jewish thing—is doomed. It can’t possibly work.”

But coexistence, he said, first required Israel to be willing to acknowledge the injustice it had inflicted. Said said he had “never argued for anything but peaceful coexistence between us and the Jews of Israel” but that it could only occur “once Israel’s military repression and dispossession of Palestinians has stopped.” “Israel can have peace,” he said, “only when the Palestinian right is first acknowledged to have been violated, and when there is apology and remorse where there is now arrogance and rhetorical bluster.”

Said articulated the anger that came from experiencing what he described as “a set of evil practices, whose overall effect is a deeply felt, humiliating injustice.” “We have been dispossessed. Our society has been destroyed. It’s very difficult to forget that.” Speaking to an Israeli journalist, Said described the its effect of occupation on those who endure it:

“I feel tremendous anger. I think it was so mindless, so utterly, utterly gratuitous, to say to us in so many ways ‘We’re not responsible for you, just go away, leave us alone, we can do what we want.’ I think this is the folly of Zionism.…I suppose that as an Israeli, you have never waited in line at a checkpoint or at the Erez crossing. It’s pretty bad. Pretty humiliating. Even for someone as privileged as I am. There is no excuse for that. The inhuman behavior toward the other is unforgivable. So my reaction is anger. Lots of anger.”

“The only way this problem is going to be settled,” he said, is, “as in South Africa,”“to face the reality squarely on the basis of coexistence and equality, with a hope of truth and reconciliation in the South African style.” That would require Israel to face up to uncomfortable truths, to abandon some of its most cherished myths. Said did not think Israel’s domination of the Palestinians could continue forever:

“I think that even the person doing the kicking has to ask himself how long he can go on kicking. At some point your leg is going to get tired. One day you’ll wake up and ask ‘What the fuck am I doing?’”

Importantly, Said did not see Palestinians as mere passive victims of settlement and occupation. He was highly critical of the existing Palestinian leadership: “I’ve spent a long time criticizing Israel and Israelis, but one must say that Palestinians have a lot to answer for. There’s very little real knowledge of Israel or of the need to address a constituency of conscience in Israel.…” Said was contemptuous of “useless terrorist actions,” saying that “violence for its own sake is to be condemned absolutely.” As a humanist, he would have had no sympathy for Hamas’ recent atrocities against Israeli civilians, even as he sought to explain the roots of the violence.

Said knew that treating people as human means treating them as having agency, and so he did not accept the argument that Palestinian resistance strategies were beyond criticism. He thought Palestinians needed to bear in mind that “most liberation struggles in the Third World have produced undistinguished regimes, dominated by state worship, unproductive bureaucracies, and repressive police forces.” He eventually spoke of Yaser Arafat and the PLO with just as much scorn as he used for Thomas Friedman of the New York Times 1:

“We need a new kind of leadership, one that can mobilize and inspire the whole Palestinian nation; we have had enough of flying visits in and out of Cairo, Rabat, and Washington, enough of lies and misleading rhetoric, enough of corruption and rank incompetence, enough of carrying on at the people’s expense, enough of servility before the Americans, enough of stupid decisions, enough of criminal incompetence and uncertainty.”

Said lamented that Palestinian leaders had fallen back on unimaginative ideas that were unlikely to be successful and believed that “armed struggle” by bands of militants against “hopeless” odd simply could not achieve the same kind of gains as a mass protest movement:

“Successful liberation movements were successful precisely because they employed creative ideas, original ideas, imaginative ideas, whereas less successful movements (like ours, alas) had a pronounced tendency to use formulas and an uninspired repetition of past slogans and past patterns of behavior. Take as a primary instance the idea of armed struggle. For decades we have relied in our minds on ideas about guns and killing, ideas that from the 1930s until today have brought us plentiful martyrs but have had little real effect either on Zionism or on our own ideas about what to do next. In our case, the fighting is done by a small brave number of people pitted against hopeless odds: stones against helicopter gunships, Merkava tanks, missiles. Yet a quick look at other movements—say, the Indian nationalist movement, the South African liberation movement, the American civil rights movement—tells us first of all that only a mass movement employing tactics and strategy that maximizes the popular element ever makes any difference on the occupier and/or oppressor. Second, only a mass movement that has been politicized and imbued with a vision of participating directly in a future of its own making, only such a movement has a historical chance of liberating itself from oppression or military occupation. The future, like the past, is built by human beings. They, and not some distant mediator or savior, provide the agency for change.”

Today, with Israel lashing out in rage at Palestinians after a horrifying Hamas attack on Israel, Said’s vision of two peoples coexisting harmoniously may seem impossibly remote. But he believed that until there was a clear “end” in mind, there could be no hope of moving toward it, and it was the job of those who wanted justice to both acknowledge that the conflict had a “right and wrong” to it and articulate a clear message of “peace with justice.” At what is perhaps the bleakest moment in the history of the Israel-Palestine conflict, his defiant but hopeful words are worth rereading:

“I still believe it is our role as a people seeking peace with justice to provide an alternative vision to Zionism’s, a vision based on equality and inclusion rather than on apartheid and exclusion.…[N]either Israelis nor Palestinians have any alternative to sharing a land that both claim. I also believe that the Al-Aqsa Intifada must be directed toward that end, even though political and cultural resistance to Israel’s reprehensible occupation policies of siege, humiliation, starvation, and collective punishment must be vigorously resisted. The Israeli military causes immense damage to Palestinians day after day: more innocent people are killed, their land destroyed or confiscated, their houses bombed and demolished, their movements circumscribed or stopped entirely. Thousands of civilians cannot find work, go to school, or receive medical treatment as a result of these Israeli actions. Such arrogance and suicidal rage against the Palestinians will bring no results except more suffering and more hatred, which is why in the end Sharon has always failed and resorted to useless murder and pillage. For our own sakes, we must rise above Zionism’s bankruptcy and continue to articulate our own message of peace with justice. If the way seems difficult, it cannot be abandoned.”

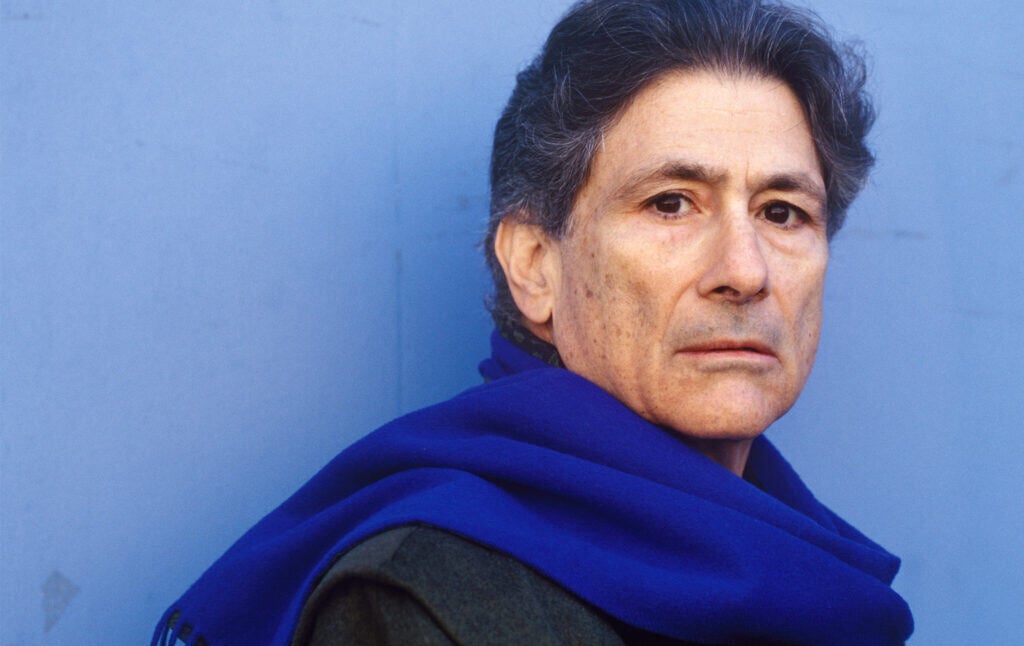

Photo by Ulf Andersen, via Getty Images

“Unabashed Zionist prophets like Thomas Friedman of the New York Times….has not one word of criticism for Israeli brutality and keeps demanding that Arabs recognize his “organic” connection as a Jew to Palestine without ever acknowledging that that right was implemented in conquest and wholesale Palestinian dispossession.” See also his review of Friedman’s bestselling From Beirut to Jerusalem, which contains sentences like “Inside this serenely untroubled cocoon of the purest race prejudice, the Friedmanian sensibility ambles from subject to subject.” ↩