How to Spot Corporate Bullshit

A new book shows that the same talking points have been recycled for centuries, to oppose every form of progressive change.

One reason it’s useful to study history is that it teaches you to spot patterns. You come to understand certain regularities in how human societies operate and how improvements in social conditions occur (or are thwarted). Seeing what has come before trains you for present-day struggles. So, for instance: when you see how propaganda campaigns against Social Security and Medicare worked in the 1940s and 1960s, you can see their echoes in present-day fearmongering about Medicare For All. And when you see how tobacco companies downplayed the risks of smoking, you understand the playbook used by the contemporary fossil fuel industry to cover up the harms of its products.

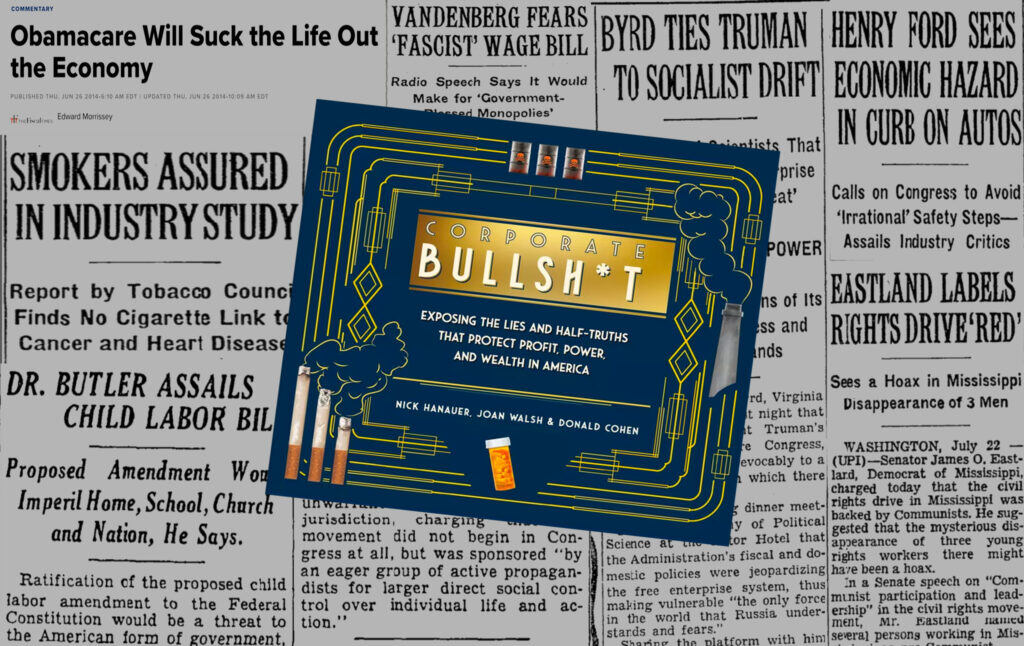

The new book Corporate Bullsh*t by Nick Hanauer, Joan Walsh, and Donald Cohen performs a useful public service by amassing a wealth of quotations from across 150 years of American social policy to show how a certain set of talking points recurs over and over in the effort to stymie progressive social change. As Hanauer writes in his preface:

Over the past century and a half, on a broad range of issues including the minimum wage, workplace safety, environmental regulations, consumer protection—even on morally indisputable issues like child labor and racial segregation—the people and corporations who profited from the status quo have effectively wielded a familiar litany of groundless ‘economic’ claims and fear mongering rhetoric in their efforts to slow or quash necessary reforms. As even a cursory examination of the quotes we’ve included in this book will show, the wealthy and powerful are willing to say anything—even the worst things imaginable—to retain their wealth and power. But while there is simply no bottom to this well of shamelessness, there is a pattern.

Over the last several decades, we have been told that “smoking doesn’t cause cancer, cars don’t cause pollution, greedy pharmaceutical companies aren’t responsible for the crisis of opioid addiction.” Recognizing the pattern is key to spotting “corporate bullshit” in the wild, and learning how to spot it is important, because, as the authors write, the stories told in corporate propaganda are often superficially plausible: “At least on the surface, they offer a civic-minded, reasonable-sounding justification for positions that in fact are motivated entirely by self-interest.” When restaurant owners say that raising the minimum wage will drive their labor costs too high and they’ll be forced to cut back on employees or close entirely, or tobacco companies declare their product harmless, those things could be true. They just happen not to be.

Hanauer, Walsh, and Cohen identify a few distinct species of bullshit, namely:

- It’s Not a Problem – The simplest strategy is outright denial. Cigarettes don’t cause cancer. Global warming isn’t happening. Child laborers are happy and learning valuable skills, or as the industry journal Coal Age said in 1912, we know “the mine is healthy” for a child because of its beneficial effects on their “muscular development and their longevity.” Enslavement is even good for the enslaved, or as John C. Calhoun said in 1837, “never before has the black race of central Africa, from the dawn of history to the present day, attained a condition so civilized and so improved.”

- The Free Market Knows Best – Even when the problem is admitted, it’s claimed that regulation is unnecessary. Hanauer, Walsh, and Cohen find that every time corporate abuses were exposed, from people dying in mines to pollution-emitting factories, industry representatives claimed that the problem would be solved without regulation because addressing the problem would be in the interests of the private sector. (Not so, of course. Dumping toxic waste and endangering “expendable” workers can be perfectly economically rational behavior.) For instance, the Chamber of Commerce asserted in 1973 that “Employers do not deliberately allow work conditions to exist which cause injury or illness. Safety is good business.”

- It’s Not Our Fault, It’s Your Fault – Corporations always claim to be acting in the interests of their workers and their customers, even if they are injuring both to benefit their shareholders. A common technique, Corporate Bullsh*t shows, is blaming the victim. In the era before seat belts and air bags, for instance, deaths in car accidents were blamed on bad driving. If people exercised personal responsibility, they would have stayed safe. Accused of endangering mine workers, for instance, the National Coal Association claimed the “fundamental cause of accidents” is “carelessness on the part of men.” Purdue Pharma, in an internal strategy memo, laid out its plan to blame addicts for the deadly effects of the company’s products. In fact, to the company, they weren’t even “addicts,” but should be referred to instead as “abusers.”

- It’s a Job Killer – This is a timeless classic. It has been said about the minimum wage ever since the 1930s, when the federal minimum wage was first introduced. But the threatened disaster never comes to pass. The authors cite the example of the Fight For 15 movement, which Hanauer was involved with. Before the city passed its $15 an hour minimum wage ordinance, Seattle-area restaurateurs were warning that the restaurant sector would be thrown into chaos by such a change. But it didn’t happen there, nor did it happen elsewhere when living wages were introduced. The warnings turned out to be nothing but more corporate bullshit. The authors say that this warning amounts to little more than a Mafioso-like threat: “Nice economy you have there, it would be a shame if anything were to happen to it.”

- You’ll Only Make It Worse – This is the old cliche that progressive reforms only “hurt the people they’re trying to help.” It’s a constant refrain. The risk of doing something is simply too high. So Mobil said in 1997 that “the science of climate change is too uncertain to mandate a plan of action that could plunge economies into turmoil.” Every horror that benefits the status quo is justified with the argument that alternatives would make everyone worse off. Corporate Bullsh*t quotes slavery defender Thomas Dew writing in 1832 that “we cannot get rid of slavery without producing greater injury to both the masters and slaves.” The authors even quote an opponent of women’s suffrage claiming that “doctors” have concluded “that thousands of children would be harmed or killed before birth by the injurious effect of untimely political excitement on their mothers” if those mothers started voting.

- It’s Socialism – Corporate Bullsh*t shows that the s-word (along with the c-word, communism) have been deployed in the most audaciously hyperbolic ways. The National Association of Manufacturers said in 1938 that the Fair Labor Standards Act “constitutes a step in the direction of communism, bolshevism, fascism, and Nazism.” Even Bill Clinton, a neoliberal who embraced Republican policy priorities, was called a socialist when he tried to make minor tweaks to the healthcare system!

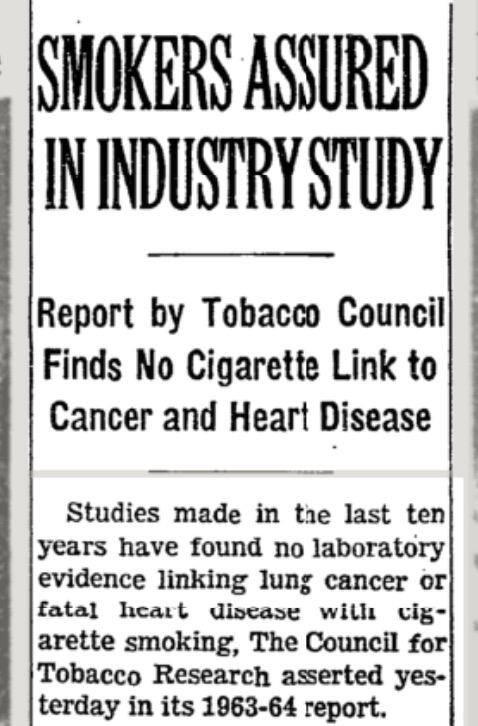

The strength of Corporate Bullsh*t is in the volume of its archival research. It’s a slim book, but it packs in tons of quotations, many of which are quite jaw-dropping and all of which demonstrate that the more things change, the more they stay the same. The book is full of astounding snippets from the historical record like this 1964 New York Times item:

Here are some other particular lowlights the authors have found in the archives: Chrysler, in 1972, claimed that there is “no scientific evidence showing a threat to health from automotive emissions in the normal, average air you breathe. Not even in crowded cities.” Lee Iacocca of Ford described seatbelts and headrests as “complete wastes of money.” Iacocca later claimed the Clean Air Act could “prevent continued production of automobiles.” The National Lead Company (1923) said that “lead helps to guard your health.” The free-market Cato Institute wrote in 2000 that “the subprime mortgage market, which makes funds available to borrowers with impaired credit or little or no credit history, offers a good example of competition at work.” (Oops!) The American Pulp and Paper Association claimed that “industrial waste is not a menace to public health.” All the rhetoric is depressingly familiar, such as the Illinois Manufacturers Association saying in 1934 that unemployment insurance would “result in further and unnecessary intrusion of the Government into the domain of private enterprise, thus aggravating the hardships which have already been caused to industry by extensive government regulations, restrictions, and competition.” The National Association of Life Underwriters said of Medicare in 1965 that it would “set up a health program which served little or no necessary social purpose and which would be a direct, unwarranted, and completely unfair intrusion in private enterprise.” Over and over we hear slight variations on familiar themes.

One of my favorite of the authors’ discoveries is a 1971 quote from Edward Annis of the American Medical Association, who attacks the right to healthcare thusly:

“Some people think that people are entitled to health care as a matter of right, whether they work or not. This is just as absurd as saying that food, clothes, and shelter are a matter of right—one step further than that is a revolutionary system bordering on communism.”

Yes, a right not to starve to death—that would be absurd, wouldn’t it?

The point here is not just to catalog history’s most shameless examples of self-interested propaganda, but to teach readers how to see through bad arguments. The authors encourage readers to engage in critical thinking: check the research methods and the funding sources behind claims—and learn to tell better stories than the other side. It’s a mission I appreciate, as it’s similar to what I’ve attempted in my own Responding to the Right: Brief Replies to 25 Conservative Arguments and our magazine’s A Student’s Guide to Resisting PragerU Propaganda. As the authors of Corporate Bullsh*t observe, for most people, it can be difficult to tell the difference between propaganda and honest argument because we simply “don’t have the time to figure out who’s right,” which is why it’s easy for corporations to sow doubt. But by learning critical thinking and being able to spot patterns based on historical regularities, we can lower the odds that we’ll be fooled.

It’s also the case that by looking at how obviously flawed these old arguments look in retrospect, we can more easily see the silliness of those made today. We now know that it was nonsense when New York manufacturers said in 1913 that fire codes would lead to “the wiping out of industry in this state.” Likewise when DuPont said in 1988 that banning chemicals that destroy the ozone layer meant “entire industries could fold.” Same when the American Liberty League said in 1935 that Social Security would be “the end of democracy.” The sheer wrongness of these confident pronouncements should make it easier to see how warnings about Medicare For All and the Green New Deal in our own time are similarly bogus.

I’m not actually sure that the bullshit in Corporate Bullsh*t is all specifically “corporate.” The authors show that the same types of arguments were even used against civil rights and women’s suffrage, where there are other power structures at work. In my own analysis of right-wing arguments, I’ve found the framework offered by Albert Hirschman in The Rhetoric of Reaction to be useful. Hirschman shows that those trying to oppose changes to the power structure—whether corporations trying to protect their wealth or men trying to protect their special privileges—deploy the same familiar tropes about how the progressive reform du jour will end civilization, hurt its intended beneficiaries, etc.

Corporate Bullsh*t will turn readers cynical, in a good way, so that we can laugh when we hear, for example, Mark Zuckerberg saying in 2021 that social media has been found to have “positive mental-health benefits” and denying that Facebook could be “mak[ing] people angry or depressed” on the grounds that the “moral, business, and product incentives” all push the company in the other direction. Here is just another version of Alan Greenspan’s claim in 1963 that “it is in the self-interest of every businessman to have a reputation for honest dealing and a quality product.” And it’s just as much nonsense now as it was then, because of course it might be in Facebook’s self-interest to make people angry or depressed, if being angry keeps people hooked on the product.

We now face, as the authors note, a world-threatening calamity in the form of climate change. “Climate change,” they write “is where the It’s Not A Problem mindset might end up doing the most catastrophic damage of all.” Corporate bullshit endangers lives, and the harms done by Big Tobacco pale next to the potential costs of the climate catastrophe created by the fossil fuel industry. Developing an eye for bullshit, and steeling oneself against it, could not be more urgent.