How Privatization Robs Us of Our Most Precious Assets

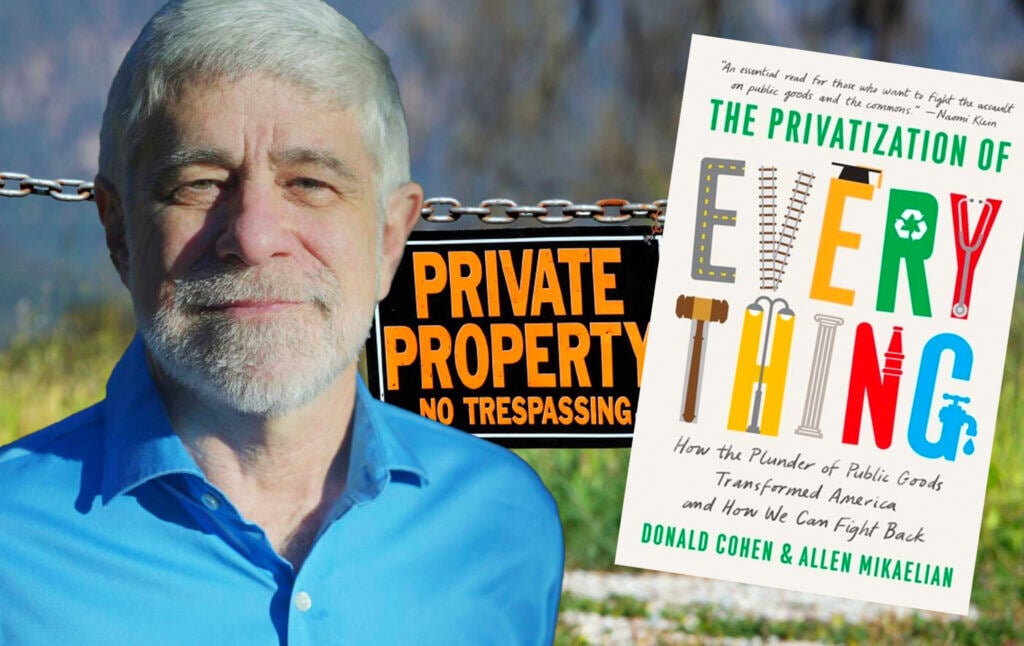

Journalist Donald Cohen on how turning public goods over to private companies is a terrible idea that causes us to have to pay for things we already own.

You name it, it’s been privatized somewhere in the United States. Schools, roads, libraries, courts, prisons, and even the law itself have been outsourced to private companies by state and local governments who buy into the idea that The Private Sector is more efficient at serving the functions of government. But this is baloney, as Donald Cohen shows in The Privatization of Everything How the Plunder of Public Goods Transformed America and How We Can Fight Back(co-written with Allen Mikaelian). Cohen, the founder and executive director of In The Public Interest, joins today to take us through case studies of privatization in action, like Chicago’s disastrous deal to sell its parking meters. Cohen shows us that when we privatize, we are turning our own assets over to someone else who will sell them back to us and pocket our money. He explains why privatization is a bad deal and why public goods and services should remain in public hands. There is a right-wing effort to stigmatize public services as Big Government (calling public schools “government schools” for instance), and Cohen makes the case for why we need a pro-public culture that unashamedly demand that what belongs to the people stays in the hands of the people.

This conversation originally appeared on the Current Affairs podcast. It has been lightly edited for grammar and clarity.

Nathan J. Robinson

It really is the privatization of everything. That is one of the key takeaways that I had from your book after going through it. You document case after case after case. People might hear about prominent cases—school privatization and so on, but you show it’s everything.

Donald Cohen

And there was plenty left on the cutting room floor. Currently, that’s the big issue about Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and direct contracting Medicare—we didn’t cover that at all. There are definitely things that we didn’t get to.

Robinson

Did you cover war and the military?

Cohen

Not really, no. That’s another big one we have to add.

Robinson

But this is not to say that this book is skimping. You do go through many case studies.

Cohen

There’s a book out now by Mariana Mazzucato about the consulting industry, which we don’t talk about as well, which is basically the brain outsourcing—government brains—to huge consulting firms. So, there are other things to explore.

Robinson

What are some of the cases of efforts to privatize, successful or not, that people might not know or realize?

Cohen

I would venture to say most, but I will give a few cases. Let me say how we define privatization. My definition is it’s about private control over public goods. Public goods, in my definition, are the things that we all need to survive, the things that we need everyone to have: health, clean air, transportation, education, all the above.

I’ll give a couple of examples because that’s the best way to get into the real issues, which our book intends to draw a through line into some larger issues that connect all the public sectors. So, parking meters in Chicago—I’ve told this story many, many times, and most people who don’t live in Chicago don’t know about it. Everyone who lives in Chicago does. In 2008, the worst of the recession, cities were bleeding red ink. The mayor at the time announced a proposal from a private consortium of Morgan Stanley from Wall Street, a sovereign wealth fund from the Middle East, and a national parking company, LAZ parking, which is basically all over the country. That consortium offered the city $1.1 billion upfront in cash in exchange for control of the city’s 36,000 parking meters for 75 years. It was announced on a Friday and the vote was on Tuesday. Now, just to put in context, 2083 is when that contract ends. So after the fact, it was analyzed and scrutinized and all that. It was a terrible deal, an unbelievably stupid way to borrow on future revenue. Everybody borrows on future revenue, that’s how we buy houses and things, but for 75 years, incredibly stupid. Prices went way up to park.

But here’s the most important thing: that for the life of the contract, if the city wants to do any one of its important jobs—transportation, land use, housing, environment, parks—and they would like to eliminate parking spots, they have to buy them back. So, if you have to buy the spots back at the future value of the spot, fundamentally, you don’t do it in many cases. In fact, there was a professor at one of the universities there that interviewed transit planners within a year or two after the deal, and found that they were unable to complete a plan to create bus rapid transit or dedicated bus lanes. If you want to create bike lanes or pedestrian laws, your hands are tied to deal with the fundamentals. So for me, what that says is that privatization is really an assault on democracy because it gives them legal contractual control over the stuff that should be ours to control.

Robinson

Do we have an estimate of how much those who bought the rights to the Chicago parking meters are going to make out of it? Presumably quite a lot.

Cohen

Quite a lot. I don’t have a number, but I do know that either now or within the next few years they will have gotten all their money back, everything else minus operations, which is great. They’re doing quite fine.

Robinson

Yes, and have a few more decades to go. One of the points that you make in the book is the Indiana toll road case as well, which has parallels. I think people might not think of it this way, but when you sell a public asset and take the check upfront for much less than what the thing is worth over the period of time that you are giving this company or consortium the right to collect revenue, you are essentially transferring wealth, just handing it over from the public sector to the private sector.

Cohen

Enormous amounts. So, the parking in Chicago needs to be modernized for credit cards and all that, like most cities are doing right now. That may cost some money, so they needed some cash, and they could have borrowed it. The rates to park went way up, I think eight bucks an hour or something like that. So my question would have been to them is: if the private entities think they can make money doing this, why can’t the city? Because the city has great needs—housing needs, climate needs; it has all sorts of municipal needs that would benefit the city. You’re exactly right. It’s pure extraction.

Robinson

And one of the things you say in the Indiana case is all these politicians tout it as this wonderful deal, and you ask: if it’s such a wonderful deal, why is the buyer offering this sum? Just look at this giant sum they’re offering. If they weren’t expecting to make a lot more from the tolls or from the parking meter revenue than they’re paying, they wouldn’t see this as such a golden opportunity.

Cohen

Some of them went bankrupt because they made bad choices, but then they’ve just changed the way they do the deals. But here’s what’s interesting about that. There’s going to be a lot of infrastructure money flowing, given the Inflation Reduction Act. There’s a lot of money that we need to build infrastructure. There are two things that are really important to remember: things cost money, and there’s only one place to get that money—us. Taxes, tolls, and fees. That’s it. The reason this is important is that the people who want to privatize, or do these public private partnerships, will often say, “no new taxes, more efficient.” It’s all motherhood and apple pie, but you have to take it back to that basic fact. It costs money, and there’s only one place to get it, and that’s us. So if rates are going to go up more than they need to, then someone else will get that money.

Robinson

Yes, there’s a wonderful story that is told. Perhaps you should give a version of what the pitch for privatization is, because it’s the same in almost every case. It’s this wonderful fantasy about how everyone is going to benefit, and we will get something for nothing.

Cohen

That’s a great question. There are a few pitches, and one is: cheaper, better, faster. The private sector is more efficient, so we can provide public services more cheaply. But let me stop on that one because we deal with this argument all the time. So they say they’re more efficient. Let’s just think about what efficiency is. Efficiency is spending or doing less and getting more—less effort for more. Well, there are two ways to be efficient. One is to do things smarter. We’ve all figured that out in our homes. But the other is to do them cheaper. So when the private sector says, “we’ll do it more efficiently,” they’re going to spend less money on something because, remember, they will take a bunch of money out.

Robinson

Yes, they have to make a profit.

Cohen

They’ll get profit. That goes out, and executive compensation. So, tell us exactly what you’re going to spend less money on because it’s very concrete and very real things: fewer workers, lower pay for workers, poor quality equipment, or less maintenance. It’s very concrete, and that’s absolutely what happens. So, that’s efficiency. Better? If someone’s got a better idea, we could buy that from them. But we don’t have to give it. There may be some private company that has some clever idea about how to do something. Well, let’s just buy it and we all do that. Faster? Not really. They say it all the time, but not really. So, that’s one thing: cheaper, better, faster, and more efficient. The other argument we hear a lot is that the public sector doesn’t have the money. So, they don’t have the money to build the new road. Again, we take that back to what I was saying earlier, but I’ll say it a little differently now. We have to borrow money to build a road, and you borrow money to build to buy a house. Borrowing is actually the easy part because, it turns out, you have to pay it back. And there’s only one place to get that—taxes, tolls, and fees: us. Let’s just break it down to the actual nuts and bolts truth of it. It’s all math.

Robinson

Yes. There are some cases where there’s this fantasy about the magic that the market works. This is particularly the case in the argument for school choice, which is that if you privatize you provide this range of options, get more consumer feedback, and then the schools are forced to get better because you’re giving the consumers the power to decide. How do you respond to that?

Cohen

What they’re saying is that competition will create innovations and make everything better. Now, we all compete and we watch sports. There’s nothing wrong with competition in the abstract. But for schools in particular, because that’s really the best example, competition isn’t all good. So, charter schools—let me talk about charter schools. I know you have a lot of them in New Orleans.

Robinson

We don’t have any public schools here, actually. They got rid of those.

Cohen

The idea of charter schools is that parents would be able to choose the charter school their child can go to, and then the money would follow the kid into the charter school. Parents and families would look around for the best school, and charter schools would then compete in the market for students. There are the distortions that occur when you do that because this happens: there are charter schools that, not legally, but programmatically, look for ways to either screen out or push out the harder to educate, more expensive kids. They do it all the time.

There was a New York Times investigation that, in New York, they found a “got to go” list that a principal had in one of the charter schools. Now, why did they do that? In the marketplace of choosing a school, one of the things a family or parent looks at are test scores, and whether it’s right or wrong, that’s something that everybody’s going to look at. If there are kids in that school that are bringing down the test scores, they won’t be as attractive in the market. Markets segregate, and markets want the best. That’s one problem. The other thing about charter schools is originally it was a good idea. They can be laboratories of innovation that can try things, but then share the results and learn new ways to teach kids. But the problem is, charter schools are now competing and don’t want to share. We haven’t done a comprehensive analysis, but we found as a condition of employment, charter school teachers have to sign an NDA—a nondisclosure agreement—that they will not share the school’s trade secrets. What are the trade secrets? Curriculum, lesson plans—the actual stuff that should be shared—and the fact that we’re paying for every bit of it.

So, it’s the distortions of the market in education that are segregating and stratifying, that are treating kids and families poorly, and creating all sorts of destruction for communities.

Robinson

The private sector may have some good incentives to satisfy consumer demand, but they also have a boatload of bad incentives. The profit motive creates all sorts of reasons why it would be good for you to do things that are socially toxic and harmful.

Cohen

The profit motive may do some good things, but the profit motive created the opioid crisis. Let’s be clear, it’s not a universal good. But I think it’s really important to remember something, also very simple. Businesses just do one thing, not good, not bad: they sell stuff. That’s it. What do they pay a lot of attention to? How much they sell, what the price of the unit is, how much it costs to make, what the profit is, and what their market share is. Those are the things that they measure. Nothing wrong with that. I’m not going to say yes or no, because we all buy and exist in the private market. But those are different interests than the public interest. Private prisons want heads in beds. The more heads and beds, the more they make. For for-profit colleges, the more butts in seats, the more they make. Those incentives create distortions, cut corners, and all sorts of negative things. We could look at many examples.

Robinson

Yes, private prisons: the less you feed them, the more you make. Just terrible incentives there.

Cohen

Exactly. And we did do research, maybe about six or seven years ago, and we got the majority of the private prison contracts at the state level. We looked at the contracts and two thirds of them, maybe a little bit more, had bed guarantees on them. The state either had to keep the beds filled at an X percent or pay at 80, 90, and some at 100 percent. It’s in their interest to keep those beds filled.

Robinson

That’s interesting. One of the things that is always said about profit is that it’s the reward for risk taking. But one of the things that seems to come up in a number of cases in the book is that when these kinds of agreements are made to either sell or lease a public asset, often it includes some provision that insulates the private sector from any risk. In the case of Chicago, they said, we’ll pay you if we want to take back any of these parking spaces, and you take on no risk whatsoever that you’ll lose your investment.

Cohen

Absolutely. I call them “make whole” clauses. The Chicago example is the worst-case scenario and everyone knows about it, but there are features of that deal that are incredibly common. Like you say, they want to be made whole, and we find them in power, water, and incinerator contracts. You may have seen the section on incinerators: keep the trash coming in or pay anyway, and so the communities don’t recycle. But here’s the thing, if it’s a public service, it can’t be subject to the creative destruction of the market. It can’t not exist. If a road goes bankrupt, the road still needs to exist because it’s a road that we need. If it’s a water system or a parking meter, these are things that in the end you cannot shift the risk because it’s stuff that we need.

Robinson

I think you sided with the incinerators—was it Detroit? A poor city that’s on the hook for paying millions and millions of dollars.

Cohen

Yes, and don’t know whether it was Detroit or one of the other places we looked at, but Covanta was the company that the municipality said, we’re not going to do recycling right now because we are contractually obligated to keep that to keep the flow into the incinerator. That gets in the way of what we want to do, which is to recycle, which is a good thing, of course.

Robinson

You want to recycle, you want to eliminate some parking spaces and put a park in, but you literally can’t do it to protect this company’s profits.

Cohen

Exactly right. Let me give you another example. You may remember the weather story. All the data for our weather apps and weather on TV, and what have you, is public and comes from the National Weather Service satellite system. So, it’s all public, which means we all pay for it. That’s fine. But then companies can process it, add to it. Some of it is legit and some of it is nonsense—just fancy graphics—but some of it is maybe legit for a company. AccuWeather is one of the big ones. The previous president nominated, unsuccessfully, the head of AccuWeather to be the head of the National Weather Service, and it didn’t happen, thankfully. So, this specific example is there was a tornado in Oklahoma in 2015, I believe it was, and one of AccuWeather’s clients was Union Pacific, the cargo rail company, and they got extra warning and extra services, and they may have been legitimate services. Here’s what the CEO of AccuWeather said after the tornado because it’s better just to use his words. He was on TV touting the benefits of private weather services and said, “Two trains stopped two miles apart, they watched a tornado go between them.” That’s a good thing they weren’t hurt. But then he goes on and says, “Unfortunately, it went into a town that didn’t have our service, and a couple of dozen people were killed, but the railroad did not lose anything,” meaning that’s the market at work. If you can pay, you can stay alive, and that’s what markets do. They exclude those that can’t afford, and they segregate.

Robinson

You also talk about in the weather chapter how there have been efforts by this industry to take public data, repackage it, and sell it to try and keep that public data from being public. There are cases where we pay for things, and then the incentive of the private companies is not just to sell us something that builds upon what we publicly made, but to become the gatekeeper so that only they can give you access to this public information.

Cohen

That’s right. The National Weather Service is not allowed to create an app that we could use. I don’t know who runs the app on my iPhone, but they’re not allowed to because of basically political power through the regulatory process of legislative precedent. There’s an issue right now, similarly, with the IRS and Free File. The tax companies—Intuit that owns TurboTax and the other ones—have created something called the Free File Alliance, one of those Orwellian names, that is working against the IRS from providing, for probably half the population, prefilled, easy, and free tax submissions. And why? TurboTax wants to sell their product and doesn’t want the public competitor in the market because the public doesn’t make a profit. The public can make it easier and isn’t traded on the stock exchange.

Robinson

Yes, it’s a real example of a product that is useless or only useful under certain conditions, which I think is also true of health insurance companies. This isn’t a product that should exist in plenty of cases because we could just provide this publicly and do a much better job.

Cohen

Exactly. We don’t have a public option under Obamacare, which would have been just a modest step, because they don’t want the competition. Again, objectively, their job is to sell stuff and to grow. Our job is to make sure they’re not getting in our way.

Robinson

You talk there about the way that a corporation, and in this case, the weather companies, are a gatekeeper for public information. It’s also striking how that occurs in academic research. You have a chapter about how oftentimes we, the public, pay for our public universities to produce knowledge, but then private companies can build a fence around and charge access for it.

Cohen

Yes. I’m not an academic, but there’s an industry of academic journals in every discipline, sub-discipline, and sub-sub-discipline that rely on scholars to do the research and the writing. But it also relies on scholars to provide peer evaluations and peer research to make sure it’s good stuff. So, there has been a massive amount of money made, and we’re already paying for it because the scholars don’t get extra money. I just can’t pull it up in my head right now, but there was some progress on that point recently, in the last year or two. There were limitations put on some of the private academic vendors, but I just I’d have to look it up.

Robinson

But as you point out, once again, there’s a wealth transfer from public universities of tax dollars to private for-profit publishers.

Cohen

It’s all a wealth transfer. Before Covid, there was about $7 trillion spent every year by governments in America. It’s a pot of gold. $100 billion in prisons, three quarters of a trillion in K-12, education. You can just go down the list, and taking the military aside, they want a piece of it. And if they get a piece of it, they take a big slice. Again, all the money comes from us, let’s just be clear. Every dollar that’s being used to pay a CEO of a company $10 million that privatized Medicaid or something like that is a dollar that’s not being used for health care. Let’s just be clear.

Robinson

Yes, and the public ends up paying for things that we already own.

Cohen

Exactly. There’s only one us. There’s no magic money. It’s all us. They’ve wrapped it in “cheaper, better, faster” and the ideas of the markets and all that mentioned earlier. The work I do is I cut right to the chase. Let’s talk about the nuts and bolts.

Robinson

We haven’t discussed how the transfer of public goods and services to the private sector has another consequence which has implications for democracy, which you mentioned earlier. Once it goes into the private sector, it often goes dark. That is to say, you don’t know what is actually going on within these institutions to the same degree that you do when you have transparent public institutions that are subject to public records requests.

Cohen

It’s exactly right. When I mentioned earlier about charter schools and trade secrets, there is an exclusion to FOIA for open records laws for confidential and proprietary information for trade secrets. You see it in all sorts of places. I’ll give another example. There was a privatized road in Texas that went from Austin to San Antonio, State Route 130. It ended up that the privates weren’t generating enough money because people weren’t using it. The road was a truck route. So the first thing they did was raise the speed limit to 85 miles per hour. With trucks going 85 miles per hour, it’s a road I wouldn’t want to be on. But then some investigative journalists tried to get the traffic projections before the road was built to determine whether the road was necessary and all that, and they were told that that was a trade secret. The courts backed them up. So, if there’s going to be a road or not, we want to make a good decision. That’s a public decision where there should be a road from one point A to point B. Projections of future traffic are key information that we should have to evaluate that, and you see that across every sector. We’ll get individual contracts, and everything gets redacted and blacked out.

Robinson

I think that, for me, one of the most extreme examples in your book was the literal privatization of the legal code itself in Georgia where the annotated Georgia statutes were put on to LexisNexis. You have to pay to even understand the law, which seems to me to be an especially dystopian form of privatization. I don’t know if you have your own favorite extreme and absurd case of something that we own slipping out of our grasp.

Cohen

The good news about that case is that the good guys won in the end, so the lawsuits did work out for people to know. But again, even in that case—I know that’s not the specific question you asked—it tells you what I said earlier: governments say we don’t have the money for this because it costs money to publish the law because the law changes. We don’t have the money for it, and by the way, the private sector does it better anyway. It should happen in the market because if people want something they should pay for it. So, the whole idea of privatization is bundled into that one. The weather is really my favorite. I’ll give another example that’s not in the book, which is similar: dorms. An increasing number of college dorms are being privatized—these public private partnerships where they build and operate them.

And so when Covid happened, everything shut down. We’re all familiar with that. There were a couple of colleges, I think Georgia State and Wayne State, that wanted to start bringing back students but socially distance at lower levels of occupancy in the dorms. They received a legal letter from the company saying, “The university does not have the unilateral right under the agreement to institute a policy that would, for example, limit the number of students who can occupy student housing.” So again, it’s about democracy. If you’re the head of a university, your responsibility is to teach students and keep them healthy and safe, but that goes against the interests of the private company that wants to make money by having kids pay their board fees.

Robinson

For a lot of the things that you discuss in the book, I really do think the word dystopian was invented to cover. But you mentioned there that the good guys can win, as in the case of Georgia. You have a few other examples of cases that are similar. I think it’s very important not to leave people feeling hopeless and that all of their public assets are just going to be privatized, the national parks will be sold off, and our democracy will just wither and die. The government is still pretty powerful, and it has the right of eminent domain. We can, in fact, if we try, seize the assets that are rightfully ours and return them to their rightful owners, i.e. the public

Cohen

That’s right. So yes, there are numerous victories happening all the time. You don’t see a lot of it because everything’s happening everywhere. But there are a few points to raise, and one is water systems. I don’t know the numbers, but there are lots of water systems that were privatized, that then ultimately became remunicipalized—that’s the word folks use. And that’s happened for a couple of reasons, and when you look at the whole set of them, one is they could save money by bringing it back in house, but the other is that they realized that it’d be better for them to have control of their water. There are too many related health and other issues to have it in the private sector. So that’s one.

A good example I use is access to the internet. It is a basic public infrastructure everybody needs. I think we’re all clear about that now, but the big telecoms have gone to state legislatures to prevent local governments from creating municipal broadband to keep out the competition. In Colorado, they did that, but left what I called a “pro-public loophole”. They said they can’t do it unless the voters of that city or that jurisdiction vote to create new civil broadband. In every case where that came to a vote, the public broadband forces won overwhelming. You think about what’s what’s going on there: people get that we all need it. Nobody likes their internet company—that helped—and they want to have access to it. We learned even more about that in Covid. We realize everyone really needs it.

Robinson

One of the things that I like about your book is that you don’t just critique privatization. In part nine of the book, “Becoming Pro-Public”, you lay out how we can think differently. You argue that we need to take back the way we think about the things that rightfully belong to us because there’s a propaganda campaign which rebrands the public as the government. You point out that, according to Republicans, public schools are government schools, and anything associated with the government or state is seen as something distant from them that is not theirs. But you lay out in this book how we should think about these things, what we are entitled to, and what is ours. So tell us, to conclude here, how we become pro-public.

Cohen

I’ll preface it by saying that negative attitudes towards government did not happen magically. There was a 40 to 50 year strategic, coordinated, and multisided effort to turn people away from government, both the idea of government and the institution of government. We could have a whole other session on the different strategies and things that they did, and it’s real. The government in America is the most complex human institution in civilized history. If you and I ran everything, we would mess it up. It’s complicated to deliver services to 300 to 400 million people. So, we do need to rebuild trust in government; government has to be worthy of our trust, so it needs to be good and resourced. That’s the truth, and there are plenty of good things that government does. If you look around your room, the paint on your wall used to have lead in it, but it was public action that literally took the lead out through government regulatory action. What I think is important and what I talk about is we first have to become clear about the idea of public. There are things that everyone needs. It’s in our interest for everyone to have, whether you have a kid or not, an educated population, and we can only accomplish that if we do it together. And that instrument is government. And so, it’s super important for us to determine that. The second thing is to realize that there’s a textbook economics definition of public goods that we reject, and I won’t get into that here.

But we think public goods can be decided democratically. We can decide everyone should have health care, that it shouldn’t matter how much you make to be healthy. We could decide that everyone should have broadband. We should be able to mail letters to every corner of America at the same price because we’ve decided that communication is key to a good society. Those decisions are ours and should be ours, and we need to get the private sector out of the way of making the fundamental decisions. We may need the private sector to do some of the things, but the market should not decide that, we should. That’s a couple of ideas. And then, like I was saying earlier, we should remember we got to pay for it, so let’s pay for it. But let’s not throw money away.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.