How Labor Movement Can Win at the Bargaining Table

Two leading experts explain how unions can fight back against dirty tricks by management.

In Current Affairs, we have previously discussed the inspiring fight waged by the Amazon Labor Union on Staten Island, and the confrontational tactics that can help unions win recognition despite the best efforts of corporations to thwart them. But even when unions win recognition, in many ways the battle is only just beginning. At Amazon and Starbucks, workers may have won recognition, but they haven’t actually gotten contracts, because the companies are ruthless at the negotiating table (and ruthless about staying away from the negotiating table). So what happens then? What do workers do in Phase II, where they need to actually get a contract?

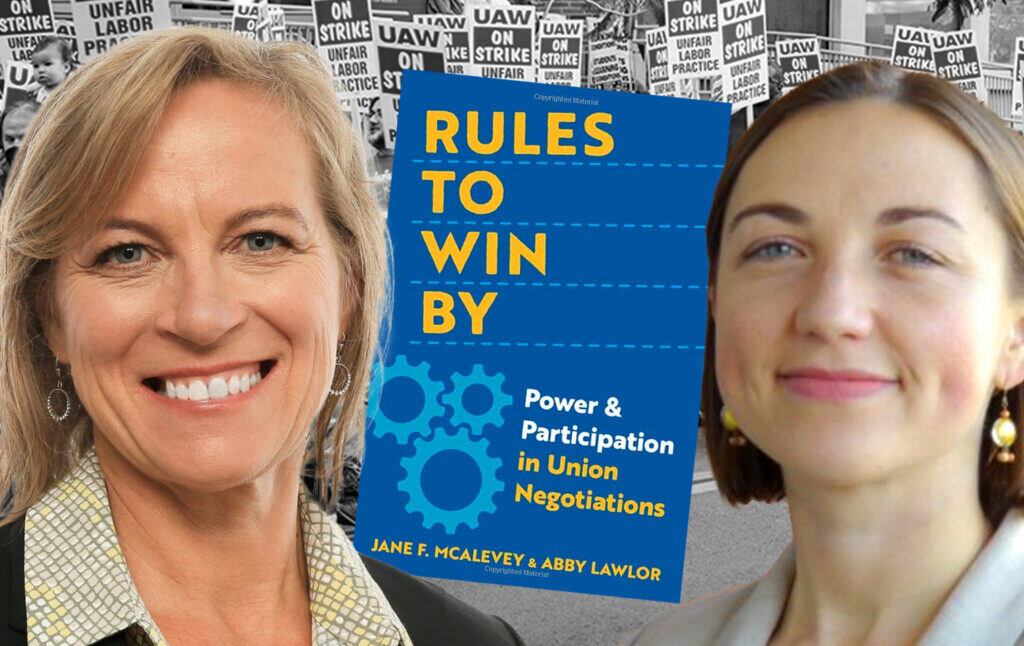

Jane McAlevey and Abby Lawlor join us today to give us some answers. Their book, Rules to Win By: Power and Participation in Union Negotiations (Oxford University Press) follows on from McAlevey’s earlier work on how to organize a union in the first place (see her previous interview with Current Affairs). They discuss how to extract concessions from intransigent employers and why the workers themselves (not an aloof, unresponsive team of professional negotiators) need to be at the heart of any negotiation. The lessons they offer are not just useful for unions, but as they explain, are practical for many other social movements who are trying to take on the powerful.

Nathan J. Robinson

I want to start by quoting something that Vox published recently, a very pessimistic take on the American labor movement:

“Every once in a while, reporters see a few successful unionization drives in the United States, like at Starbucks or Amazon, and conclude the US is in the midst of a labor union resurgence, that unions are booming or they’re suddenly and rapidly rebounding. But we have to be honest about the situation. Organized labor is not booming, rebounding, or in a resurgence of any kind. Instead, it’s in decline, as it has been for many years.”

Your new book focuses on the tactical, but before we get to the nitty-gritty, I want to dwell a little bit on the big picture of where we are and the context for all of this. Do you think that what I have just read is an accurate assessment of the lay of the land?

Jane McAlevey

I think no. I think the first part of what the person said is somewhat accurate. There are these moments and people think, “now it’s coming back again,” and what we bump up against is the extraordinary power of the union busters, in the United States in particular. And what’s interesting and different this time around, speaking to that piece that you just read, is one encouraging thing right now is that there’s a real interest and explicit discussion about the role of union busting in this country, and the need to, frankly, try and rein these folks in, contain and curtail them. Certainly, I think Abby and I think the book contributes to a dialogue in terms of the many ways to do it in terms of how to handle the negotiations and overcome them, in particular, in the first contract context, which is where the union busters are still very much alive.

So, I would say the excitement is real and the mobilization of forces on the ground right now is actually quite substantial. The young people who are bringing energy into today’s revival moment, buoyed by the record high support for trade unions in the general public, has led to a more growing awareness, frankly, that there’s a real problem with union busting in the United States. People going into these fights understand that it’s not going to be an easy fight. So I would say what’s more encouraging right now, in a post-Bernie Sanders running for president campaigns and kind of post-pandemic moment that we’re in, is there’s really broad anger. The kind of usual tropes that investors use to dissuade people from forming unions don’t hold up in the way that they did, in part because of the incredible abuses that workers just suffered under the pandemic. That would be my first quick reaction.

Robinson

Abby, how do you feel when you hear someone say “organized labor continues to be in decline”?

Abby Lawlor

I think, just numerically, that’s a reality we have to sit with. And also, I am predisposed to look for the sources of hope. I think what Jane described in terms of both people’s knowledge, understanding, and willingness to take on the really hard fights that it takes to organize, the growth there has been really exciting. And in terms of just thinking about how to scale up a movement that could grow at the speed that the labor movement has in moments historically, I’m really excited to see just all the work that’s going into creating training spaces and reading groups. And in our book, I want to count among those materials of just vastly expanding the number of people who have the skills and knowledge to do the organizing that needs to happen for us to stop the decline and to start to grow the movement moving forward. So, that’s my more hopeful take on where I hope things are headed.

Robinson

By reading that I am not just trying to confront you with a pessimistic perspective that the labor movement is still in decline, but only saying that I share the impression that we are building the foundation of something, but the very hard work of actually growing in density in the United States remains ahead of us. Jane, the last time you were on the Current Affairs program, you discussed some of the broad questions of how to build the labor movement in the United States. But this book that you have both just put out, is, I don’t want to say narrow, but it is focused on what individual unions do to exact concessions from employers. Perhaps we could start with where your book fits in the task that lies ahead of us.

McAlevey

First of all, I think the use of the word “narrow” is interesting for me because it seems like we’re trying to draw a very broad message, which is about participation broadly and how it undergirds democracy, which is an analogy that we make in the opening, but also in the concluding chapter. So, it’s a sort of larger argument that the more people understand how power works, the more capable they are of actually overcoming the kind of obstacles that are thrown in their face along the way. Where it fits, in part, is trying to open up a topic that has not ever actually been covered in the literature, which is the mechanics of negotiations. But it’s really about the principles of democracy and the trade union and what it means to involve, invite, and engage workers to the most important decision that most workers engage in a union for, which is what’s going to be in their union contract. And to the degree that we are pushing hard in the book on examples of when you open up the negotiations process and when workers come to understand who their employer really is—whether it’s in a first contract fight, like we’re dealing with in a number of cases right now, from REI to Trader Joe’s to fill in the blank—we’re arguing that in fact, the more you open up the process for people to understand it, the more capable they are of actually overcoming both the union busters, and in a larger argument, defeating the kind of disinformation and misinformation polarization that’s happening in our democracy writ large.

Lawlor

I’ll say that, first, very few workers are in a union to begin with, and folks who are in unions often only see the way that their particular union practices negotiations and have no sense necessarily of ways in which it could be different from how their union has always done it. So, I think this book serves a particular role in providing real examples for people of how other unions have approached negotiations, and then also some kind of core principles that people can bring in thinking about how to do negotiations differently and better.

McAlevey

Yes, I have one more comment. When I sat down and began to work on it, I had the extreme pleasure, fortune, luck, and many other things to then drag Abby into this process, who made it so much easier and better. But when I began to work on this, I was thinking of it as a direct extension of No Shortcuts. In other words, what we’re introducing is an organizer’s approach to negotiations. If No Shortcuts was focused on laying out a set of principles that delineated how to build power and an organizing campaign, this is essentially an extension of an argument that says, when you involve mass participation really fundamentally in every decision that you’re making, including the most important one for most workers, that’s an organizing approach to negotiations versus advocacy—a kind of mobilizing approach to negotiation. So, it’s an extension of an argument about mass participation at the most fundamental level, and that’s what it’s going to take to actually overcome the decline that we’ve been experiencing for so long.

Robinson

I want to get into that in more detail. Certainly, in the press there obviously isn’t enough labor coverage, but when there is coverage of the labor movement, it’s often about the fight to win union recognition in the first place. What happens afterward, the somewhat unsexy part, the contract negotiations, gets somewhat less attention. Certainly, I see less coverage of, for example, the Amazon Labor Union after winning recognition than the fight to win recognition. But it’s so important. Just getting the union recognized is half the battle, and then you actually have to get your contract. So, I think what’s cool about this is that you draw attention to the actual important part of what you’re going to get for your members as a union.

Lawlor

Yes, I think that’s right. And to Jane’s point about building on No Shortcuts and the organizing principles there, it’s how to carry through all the good work that people did to win their union, and how they can then carry that forward into the negotiations process itself. And that’s often a moment where there’s sort of a shift in terms of the staffing of those campaigns on the union side, from organizing to having more of a representative at the table. And so, for workers to be able to carry through their participation and their organization, from recognition into the first contract fight, I think is really key to maintaining that participation over time. I think something we really wanted to highlight in the book was that union busting doesn’t stop when workers win recognition. It ramps up, if anything, as the boss gets another bite at the apple in busting the union to prevent that first contract from ever being settled. To be prepared for that, and to really take that on through good organizing, is just so important if workers are going to actually be able to get a first contract at the end of the day.

Robinson

Jane, can I ask you if the following is a fair characterization of your views: You are associated with, shall we say, the argument that mass participation and democracy within unions are not just a luxury, but pragmatic, essential, and strategically necessary. But there can be a way of thinking that suggests that’s all great for winning the election, but once the election is won, then you designate the negotiators, and they go off and try and negotiate the contract. But in this book, it seems like one of the core arguments is, no, that principle of mass participation being strategically important applies through the entire process.

McAlevey

Yes. And not only to the entire process, by the way, but through the life of the worker and their union, just to be clear. I think part of what we’re trying to argue is, and it’s certainly my life experience, that when you’re in the crush of a National Labor Relations Board election, workers are working incredibly hard just to overcome the union busters in most cases. Solidarity and trust are being built. At the heart of winning a union drive is trust building and identifying those key worker leaders who actually have enough trust of their co-workers to help lead them to victory.

What happens in the first contract phase is the development of governing power and centering worker leaders themselves as learning how to take control of their workplace. So, if the election campaign is more about, “this is a lot harder than we thought, our boss hires his professionals, they’re really tough, we got to overcome this, it is holy hell warfare,” what begins to happen, assuming you get past recognition and to the first contract phase, in my life experience it’s where you begin to take more time to have the workers themselves who are often really smart about changes that would make their workplace actually better—not just for the workers in them, but for people who are either on the receiving end of the services, patients in the context of health care, students and parents in the context of education, etc.—it’s that workers get to bring their innate intelligence about how the workplace should be run, and then learn how to negotiate—literally negotiate—contend with, and overcome a sort of top-down dictatorship of the minority approach by management, which is what exists in most workplaces outside of workers forming a union.

There’s so little experience in the United States of workers in the working class getting the experience of what it means to govern and actually run something. That’s part of why I think we thought the book was urgent. So, the first contract and then the successor agreements are literally a worker sitting down and saying, how do we want the workplace to work, now that we’ve overcome the campaign? The campaign is a very different focus. And when you get to the phase of getting to sit down with the employer, you’re involving the whole of the workforce. Then the discussion is about workers beginning to dream and bringing their serious expertise from 10 or 20 years on the job.

I’ll give you an example from a conversation we were having last night with some worker leaders about a contract campaign they had just won in Louisville, Kentucky. One of the worker leaders, who had gone through a very difficult successor contract negotiation, where they beat back some really racist and awful proposals by management, said, “When management looked at us and looked at me as the chief negotiator”—a worker named Lillian Brenton—she said, “management thought they were just looking at a 15-year bus driver when actually I and all the workers had more experience than any of the managers in the day to day running of a public transit system.”

So actually, it’s the contract phase where you say we’re going to rewrite the rules of how this place works not just for wages and working conditions, but for that old expression of controlling the production decisions. We can make a better workplace than management most of the time. And then they’re also building the power and the understanding that to be able to enforce the future contract that they win, they actually have to learn how to hold management accountable to the contract they’re going to win, and that will take a lot of power. It’s not going to work through the grievance process. It’s not going to work by filing objections five years later. It’s about whether workers learn what it takes to manage and control the workplace.

Again, not just their wages and their benefits, but really, how do we create a better quality of life? So, it’s on the output and on controlling production. It’s on all of it, and we could go through plenty of examples of that. But really the first contract phase, in particular, is where workers learn to take their brilliance and their expertise and begin to challenge management in the governance of the whole of their workplace.

Robinson

Abby, could you help me understand a little more the contrast between the approach that you lay out in this book and what an alternate approach that you would see as less effective would be? If you’re laying out the argument for mass participation and inclusion, how does that differ from the way that things are either traditionally done or could be done that you’re saying not to do?

Lawlor

Yes, absolutely. So we call the approach that we argue for in the book high participation or high-power negotiations, and that has three core elements baked into it. Negotiations that are big, open, and transparent. And I can unpack each of those and do a little bit of contrasting with the worst of what we see in union negotiations. Let’s start with transparency. We unfortunately see in many union negotiations the workers and management will walk in for the first day of negotiations, and the first thing on the table is a set of ground rules that contains a gag order that would prevent any of the folks on the union’s bargaining committee from sharing with their co-workers—with people in the bargaining unit—what is happening in those negotiations. So, point number one on transparency is there can be no gag orders and no ground rules that would prevent workers from learning about what’s actually going on in the negotiations process, and similarly, really push for fast, clear, widespread communication about everything that’s happening in the negotiation session, so people are totally up to speed and knowledgeable about what’s going on.

In terms of the element of big, we’re advocating for the bargaining team that’s actually sitting at the table with management making decisions on proposals to be large and representative of all the different types of workers who are in a bargaining unit, so that’s all the different departments: people on the day shift and the night shift and having workers represent those different shifts that people are on, as contrasted with a bargaining team that is maybe three, four, or five people. Maybe people who are on the executive committee of the union or position holders all come from the same department or area of the workplace where there’s traditionally been a lot of union activity, but it’s not a group of people that’s representative or reaching all the different corners of the bargaining unit.

And then, lastly, on open sessions, we advocate for sessions that are open for anyone who’s covered by the collective bargaining agreement to be able to come and attend. That’s a very different approach than the more traditional approach of only the bargaining team in the room, and no other workers are there to be able to observe what’s happening.

Robinson

These sound like they would be justifiable on their own as matters of principle. Workers deserve to have a seat at the table. They deserve transparency in negotiations, and if anyone claims to speak on their behalf, they should know what is being said on their behalf. But in the book, you argue that this is also good practice for getting the results that you want. Explain to us why you argue that these principles are not just matters of principle, but are also pragmatic.

Lawlor

Sure. I think sitting on them being a matter of principle is important. Unions are fundamentally democratic organizations, having this democratic practice within them and within their internal function, I think is important in itself, but also, as we see—to illustrate through examples of a bunch of really amazing campaigns—you also just win more when you adopt these principles.

To go back to gag rules, there’s, in my mind, no effective way to mobilize people to fight back against a really nasty management proposal. In the Louisville example Jane just gave of there being a proposal on the table that would give vastly different raises to white workers versus Black workers, if the people on that bargaining team weren’t able to actually share that proposal with the broader workforce and tell them about what was happening in that room, there’d be no way for them to organize and fight back against that by using their collective power at work.

So I think that’s just one example of it being so fundamental for people to actually know what’s going on in the negotiations room, to actually really understand it, to understand the fight that they’re up against in their negotiations, and for them to be bought into the kind of organizing that it’s going to take to fight back and to win the kind of contract that they want.

McAlevey

Just to add on to that, part of what we’re trying to say is that transparency is fundamental. Most negotiations are covered by a kind of gag order, which is extraordinary. So, going back to how to overcome the decline and rebuild the movement, let’s start by being part of this argument. It’s about, let’s start by changing the things that we’re in control of. So, let’s bring workers into the process as fundamental partners, but transparency alone is insufficient. It’s transparency, plus structured mass participation on the part of the working class so that they can then go on to win, but it’s really hard to involve, depending on the size of the workplace, hundreds, thousands, or tens of thousands. If you can’t even trust the workforce enough to understand the dynamics that are going on in their own negotiations, it’s a pretty direct signal to the workers that their voice is not as meaningful as it needs to be in the life of your own organization.

We could have written a book that said you just need to be transparent, but that’s not sufficient, actually, to win. To your point about tactics and strategy, the principles of democracy—small “d” democracy—are central in the work we do. But yes, for it to be strategic, it has to be the three components that we lay out and that Abby articulated, which is transparency is fundamental, in addition to big and representative, and then open to all the workers. That’s the way to build towards something like a 95% or 100% out strike, and that’s the part of the extension of the argument from No Shortcuts. We get that kind of participation when we take a different kind of approach to the work, and that’s what leads us to mass victories and contracts that are shockingly good today versus most of what is passing for a sorry standard of working in America.

Robinson

Some of our readers may hear what you’re saying, the principles that you’ve laid out here, and think, “that sounds reasonable,” or even, “that sounds obvious.” But what you have indicated is that the methods that you’re advocating are not currently the predominant methods used by American labor unions in existing negotiations.

McAlevey

Yes, absolutely. Sadly. Let’s just pause for a moment on encouragement, though. Since we sat down to do the book, we’ve had two different reform movements, one of the Teamsters and one of the United Auto Workers, where what exactly is happening is it’s not exactly here yet, but we know already there’s a lot more willingness to be transparent. We don’t yet know the shape of how the negotiations themselves work, but with those two exceptions at the national level, and then the Amalgamated Transit Workers Union, who just in October 2022 actually moved I think the first of its kind resolution to move all of their local unions to transparent, big, and open negotiation. So that’s at the more international level, as American unions like to say—US and Canadian unions, principally.

So there are encouraging signs about where this is going right now. But honestly, the vast majority of unions sign ground rules that greatly constrain their own capacity to engage their own workers, which is extraordinary, really.

Lawlor

Again, many unions do contract surveys, but it’s really not something that they’re tracking, that they have any particular goal around, and that they’re using in any way to build organization or structure. So, we’re trying to take this thing that unions already do, but show how it can serve them. Just that basic function of actually gathering broad input on what should be in the contract, which a lot of negotiation surveys, because of just really low participation, don’t even serve that function, but are also a key step in really building the kind of organization that you’re going to need to build to a strike threat or an actual strike to win what you have on the table in negotiations.

Another one I’ll just throw out really quickly is to plug the appendix of the book because we really wanted to put these tools directly in people’s hands so that they could use them in negotiations, and that’s the three rules of the room. We have a little handout that people can use that actually has those, but just as a tool for people to kind of get on the same page and have a shared set of expectations about how people are going to behave when they’re attending negotiation sessions, making sure that there’s a way for anyone to pass notes to the lead negotiator if they have a thing that comes up during the session that they want to flag, or they want to call a caucus so that you can kick management out of the room for a couple of minutes and have a conversation just among workers.

And just on the union side, another important rule is to have one designated spokesperson at the table who can pick up those notes, but that there’s clear communication in terms of who’s talking. And then poker face: showing no reaction, positive or negative, to the proposals that are coming across the table from the other side so that you don’t give them that tip on how you’re feeling.

Robinson

In the book, you say that many people don’t realize when they go into this, necessarily, how absurd and vicious the union busters’ misinformation, intimidation, rule breaking, sore losing, and procedural warfare can be.

Let’s say you’re speaking to a group of young labor organizers who are thrilled that they’re about to win their union election and recognition, and you’re going to warn them about what they’re about to face in this contract process. What do you mean by these “absurd and vicious” tactics that will be employed? What can be expected?

McAlevey

The sky is the limit here. If you start with what we’re looking at right now, whether it’s at Starbucks or Amazon, or some of the recent examples distinct from the book, you will see that just getting to the negotiations table is half the fight, literally. At Amazon’s JFK8, the workers really clearly won the election and there has not yet been what we call a legal recognition of the union and not even close to getting into the negotiations table. And Howard Schultz, union buster supreme at the moment, is taking a different tactic about stalling. Even though some of those shops have gotten recognition, they’re taking a set of completely different tactics: delay; refuse to show up; refuse to come into the room; refuse to get information.

There’s such a long list of tools that the union busters have and that they use. I think that both the principle and the strategy that good organizing engages is to be very transparent and upfront with workers in the context of new organizing work and trying to get that first contract. It’s about actually outlining all of that to people and letting them know that they’re going to try and delay this for at least 12 months, assuming that the union gets certified. At the 12-month mark is when the union busters can come back. Under labor law—which I often call management law because it’s so stacked against workers—and once a union gets recognized, there’s a 12-month period by which there’s a bar from what’s called decertification of the union, which is why, on average, it takes 400 something odd days to actually even get a first contract.

It’s a direct incentive to the union busters to stall, delay, do nothing, drag their feet, and if they do show up, show up and do very little, leave, and not give another negotiations date for another long period of time and try and get to that 12 month mark where, frankly, they are going to inspire a second election to throw the union out. And we’re seeing that right now in the earliest elections at Starbucks in Buffalo, New York, which is where the campaign began. The Labor Board has been playing an interesting role here, but there’s an attempt to do just that, where they have delayed for beyond 12 months, and technically under the law, it’s workers who have to file this petition and then sort of vote the union out because there is no contract.

Literally management will refuse to get in the room, or delay, or refuse to do much of anything for 12 months, and then at 12 months and a day, the first really sophisticated flyer comes out that says, why even have a union? 12 months later, you don’t even have a contract. So, these guys are just brilliant at union busting tactics. They’re only able to put that fire out because they’re using delay and stall tactics along the way. Central to this is making sure workers understand so that they don’t fall prey to that argument, that you explain to them upfront there’s going to be two rounds to this fight.

And in order to get through the round that will change the terms of your working conditions, and potentially, frankly, if it’s a great contract, change your home life too, you will have to understand this as a two stage fight. That’s one of the most important things to do up front. And then secondly, again, it’s not just that you can go into the governing period, where workers learn to synthesize their intelligence and figure out how to have a better workplace run.

But it’s also a phase where they can begin to do the kind of work that we outlined in the book about really strategically involving the broader community in the campaign, and explaining all these things to the broader community as well themselves—not staff hired by a union, but rank and file workers drawing the connections to their own community, and then educating their community to bring them into the fight, which both gives workers more confidence to stay the course in the fight itself. But also, as you said in the beginning, that is strategic because it’s just going to bring more power to the fight. It’s going to have them bringing the faith community, the city council, the elected leadership. We could go through all the examples of what a really effective high participation campaign does. But the more participating, the broader the community campaign will be, too.

Robinson

To conclude and bring this back to where we started, it’s very easy to tell a pessimistic story. It is very easy to pour cold water on victories that have occurred and say union density hasn’t increased, or, you’ll win your election, but then you’ll lose the contract fight, as all these tactics will be deployed against you in a rigged system. But one of the messages that comes out of the book is that you are determined to help people win and believe it can happen. And in fact, you tell us some stories in the book of how it can and has happened. And so, perhaps we could conclude with a little bit of, if not optimism, at least determination that if you follow the “rules to win by”, you might actually win.

Lawlor

I think both optimism and determination. In a position in my day job, I think a lot about the impact that new technology is having on workers. There’s just such a glaring absence of any lawmaking that’s going to protect workers from surveillance from new technology coming into the workplace. And then I look at what hotel workers were able to do in Boston. By organizing and fighting through their contract and going on strike, they won protections from their jobs being taken away by new technology coming into the hotels. That was something that they just went out and did because it was a real threat that they were facing in their work. They made it happen through their sheer organization and guts and by being out on the street in Boston in November, in the rain in the snow, and they now have this protection that workers around the country desperately need. They went out and made it happen.

So that thing, to me, is just one example of the tremendous potential of what we get when workers have a real voice in their workplace. It’s just an incredible example of people making that happen for themselves, and gives me a lot of hope for the future.

McAlevey

In addition to that, I completely agree with that example of technology and where workers are actually way ahead of the law. Part of what we argue is that contracts and collective bargaining are a form of public policy. It just is. Collective bargaining and the standards that have been achieved in negotiations in this country for all time set the sort of floor for what the rest of workers in the country get. So, it’s really in everybody’s interest that workers continue to achieve really great contracts.

The book is filled with examples of how to do that. In the case of Einstein, that’s even an example of an incredibly vicious union busting campaign. And frankly, from election to contract, we’re talking about a matter of seven months. This is with legal charges up the wazoo. This is with going to the Labor Board. This is a union buster who alleged that the union cheated, that the Labor Board cheated, and this is the same argument that the Amazon lawyers were using.

They actually sued the Labor Board in that Philadelphia election that I’ve talked about in the book, and despite that, the workers went on to win a tremendous contract in a relatively very short amount of time. Why? Because they did an incredible job organizing both their co-workers and the whole of their community to stand with them in the face of what was a $1.1 million union busting operation. So, it’s absolutely possible and that is what we are laying out and showing and will continue to show. And the example that Abby and I have referenced now is just from a story I wrote in The Nation magazine a couple of months ago because now we’re hearing numerous stories of local victories, with people using some of these core principles and already showing wins that would not be possible if they were doing traditional closed down negotiations. There’s a lot to be encouraged about right now.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.