Seven People They Never Told You Were Socialists

Radicals consistently have their radicalism erased. Never forget the values people actually held or the causes they actually fought for.

I attended a very good U.S. public school, which means that I learned very little about history. Oh, I learned plenty in American history class about the Smoot-Hawley Tariff and the fight over the Second Bank of the United States. But I didn’t learn much about popular resistance movements, except for classic bullet points about Rosa Parks being a tired woman who didn’t feel like giving up her seat one day (rather than a committed radical political organizer who admired Malcolm X and Angela Davis and opposed U.S. imperialism). I did learn about John Brown, and a highlight of my middle school years was getting to play him in a mock trial and give a defiant, wild-eyed speech about why higher moral commitments justify lawbreaking (if memory serves, my classmates convicted me unanimously). But it was not until college that I was taught about radicals, or understood just what social movements were and what it takes to make them succeed.

I also recall being surprised at just how many notable historical figures were far more politically radical than I had previously known. Thankfully, the efforts of historians and popularizing publications like Jacobin have made it far more common knowledge that someone like, say, Martin Luther King Jr., was not just a Nice Man Who Wanted Everyone To Hold Hands And Forget About Race. But I still get angry when I realize how many people’s most cherished commitments are totally erased after their deaths, their legacies sanitized. So let’s have a quick refresher, and remember them as they would wish to have been remembered: not just as people who did Great Deeds and thought Interesting Thoughts, but as people who were part of a movement to bring about radical economic and political change.

Helen Keller

“The creators of wealth are entitled to all they create. Thus they find themselves pitted against the whole profit-making system. They declare that there can be no compromise so long as the majority of the working class lives in want while the master class lives in luxury. They insist that there can be no peace until the workers organize as a class, take possession of the resources of the earth and the machinery of production and distribution and abolish the wage system.” — Helen Keller

When I was in elementary or middle school, we were shown a highly-regarded 1962 film called The Miracle Worker, which is based on the early life of Helen Keller, who overcame an inability to see or hear thanks to the persistent efforts of a skilled tutor. It is an inspirational story and the two leads are very well-acted by Patty Duke (as Helen) and Anne Bancroft (as the tutor, Anne Sullivan). The film, however, contains nothing (as far as I can recall) about Keller’s actual life as an activist, not just on behalf of those with disabilities, but also for the labor movement. Keller was a committed member of the Industrial Workers of the World and a supporter of Eugene Debs. In fact, reading her socialist writings can be quite shocking, because she is absolutely staunch in her hatred of capitalism. Keller issued a biting rebuke to the New York Times when it printed an editorial heaping scorn on the “red flag” after the paper had asked her to contribute an article:

I love the red flag and what it symbolizes to me and other Socialists. I have a red flag hanging in my study, and if I could I should gladly march with it past the office of the Times and let all the reporters and photographers make the most of the spectacle. According to the inclusive condemnation of the Times I have forfeited all right to respect and sympathy, and I am to be regarded with suspicion. Yet the editor of the Times wants me to write him an article!

Keller was similarly scathing towards a paper called the Brooklyn Eagle, which suggested that her socialist politics were a product of her disabilities. Keller recalled that the editor of the Eagle had once heaped praise on her intelligence—before he knew she was a socialist:

At that time the compliments he paid me were so generous that I blush to remember them. But now that I have come out for socialism he reminds me and the public that I am blind and deaf and especially liable to error. I must have shrunk in intelligence during the years since I met him. Surely it is his turn to blush.

Keller said the editor should “fight fair” and “attack my ideas and oppose the aims and arguments of Socialism” rather than engaging in the low tactic of “remind[ing] me and others that I cannot see or hear.” In fact, she wrote, the editor was far more blind and deaf than she herself was, because he refused to see injustices that she herself perceived clearly. The Eagle, that “ungallant bird,” suffered from “Industrial Blindness and Social Deafness,” neither seeing the operations of the wage system clearly nor hearing the anguish of those whose lives were crushed by the pursuit of profit.

Jack London

In 1905, Call of the Wild author Jack London wrote a powerful essay about his journey from capitalistic individualism to socialism. London’s essay fits well with Keller’s writings, not only because they were active during the same period, but because London explains that one reason he was not a socialist when he was young was that when he was young he did not suffer from any physical disabilities. He was, he says, physically fit and felt capable of anything. So, he writes, it was very easy for him to adopt the kind of “self-reliance” philosophy that we still hear today: if people don’t make it, it’s their own fault, they just didn’t try hard enough. He thought of himself as a “blond-beast” “lustfully roving and conquering by sheer superiority and strength.” But London went and roamed the county, and on his travels he found “all sorts of men, many of whom had once been as good as myself and just as blond-beast; sailor-men, soldier-men, labor-men, all wrenched and distorted and twisted out of shape by toil and hardship and accident, and cast adrift by their masters like so many old horses.” London listened to their stories, and realized that despite his feelings of strength, he was in fact only an accident away from being cast aside like an old horse himself. He felt, he says, a certain “terror”: “What when my strength failed?” What would he do when he couldn’t work “shoulder to shoulder with the strong men who were as yet babes unborn”? London realized that not everyone in the universe had the advantages that he himself had, and that other people who suffered did not do so because they were morally worse or personally irresponsible. This realization, London said, made him a socialist even before he actually started reading deeply in socialist political and economic theory.

Albert Einstein

It takes a fearsome intellect to get to the point where your name literally become synonymous with “genius.” But Einstein’s legend invites a clear follow-up question: if one of the greatest minds in the history of the sciences was committed to socialist values, doesn’t this suggest that socialist values might at least be worthy of serious consideration? (Of course, people who are brilliant at one thing can be idiots at nearly everything else, so the fact that Einstein was correct about relativity doesn’t mean he was correct about socialism, but I think his level of obvious thoughtfulness means he’s entitled to at least have his ideas taken seriously.) In his famous 1949 article “Why Socialism?” in the Monthly Review, Einstein gave a very succinct explanation of the irrationality of capitalism that resonates to this day:

Private capital tends to become concentrated in few hands, partly because of competition among the capitalists, and partly because technological development and the increasing division of labor encourage the formation of larger units of production at the expense of smaller ones. The result of these developments is an oligarchy of private capital the enormous power of which cannot be effectively checked even by a democratically organized political society. This is true since the members of legislative bodies are selected by political parties, largely financed or otherwise influenced by private capitalists who, for all practical purposes, separate the electorate from the legislature. The consequence is that the representatives of the people do not in fact sufficiently protect the interests of the underprivileged sections of the population. Moreover, under existing conditions, private capitalists inevitably control, directly or indirectly, the main sources of information (press, radio, education). It is thus extremely difficult, and indeed in most cases quite impossible, for the individual citizen to come to objective conclusions and to make intelligent use of his political rights.

As I say, there is no necessary correlation between scientific genius and political insight, but in Einstein’s case he was insightful on both. His explanation of the inherent problems with a capitalistic economy is spot-on, and 75 years later it’s very clear he was correct.

Read a Current Affairs article on the political views of Albert Einstein here.

Martin Luther King Jr.

I have recently written a long article about King’s political and economic thought, so I won’t rehash too much of that here. King was not just an opponent of racism, but of militarism and capitalism as well, and he alienated many (even in the civil rights movement) with his insistence on denouncing the atrocity of the Vietnam War. King’s final book Where Do We Go From Here? should be required reading in schools. It goes well beyond civil rights, discussing what a fair economy would look like and giving his tentative answers to the title question.

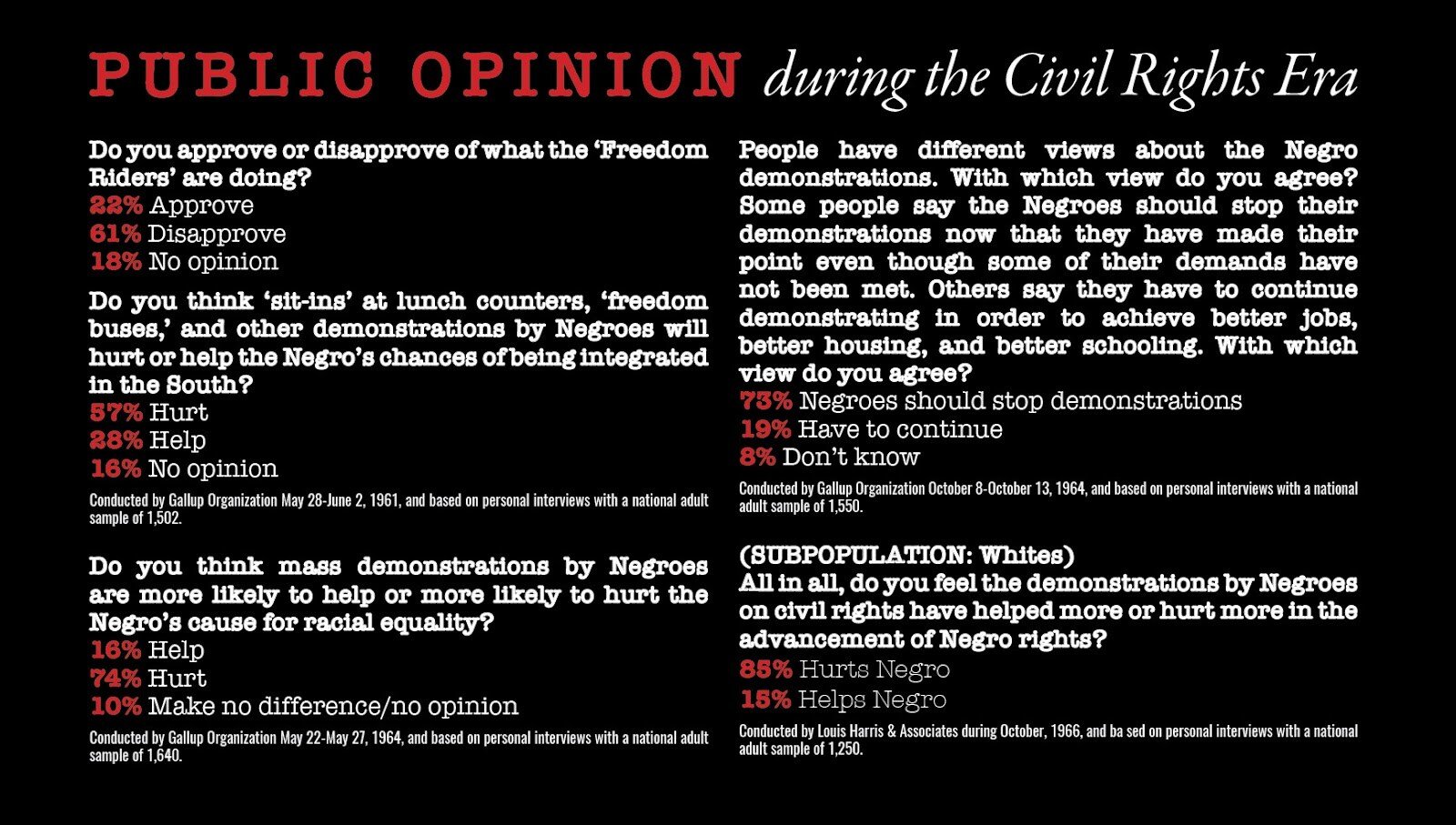

One thing to remember when conservatives push the “Cuddly King” image is that in his day, King was widely despised as a radical and agitator who was destabilizing the country. Polling from the time is striking in showing that the civil rights movement was deeply “divisive.” It wasn’t just a handful of Southern racist sheriffs objecting to King’s agenda:

This should give us some encouragement, for we can see that those who are correct about the injustices of their time (and ultimately vindicated) can be quite unpopular among their contemporaries. Being on the left can be lonely and tough sometimes, because it’s very much an uphill fight, but so were all of the struggles in history that were worth waging.

“There is nothing to prevent us from paying adequate wages to schoolteachers, social workers and other servants of the public to insure that we have the best available personnel in these positions which are charged with the responsibility of guiding our future generations. There is nothing but a lack of social vision to prevent us from paying an adequate wage to every American citizen whether he be a hospital worker, laundry worker, maid or day laborer. There is nothing except shortsightedness to prevent us from guaranteeing an annual minimum—and livable—income for every American family. There is nothing, except a tragic death wish, to prevent us from reordering our priorities, so that the pursuit of peace will take precedence over the pursuit of war. There is nothing to keep us from remolding a recalcitrant status quo with bruised hands until we have fashioned it into a brotherhood.” — Martin Luther King Jr.

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde’s image is as something of a dandy or fop, someone who made witticisms while reclining in a drawing room. But Wilde’s essay “The Soul of Man Under Socialism” is a classic text on the relationship between “individualism” and “socialism.” Wilde explains that the purpose of guaranteeing people a basic standard of living is that it would actually free their individuality to flourish. Wilde (like the great “Arts and Crafts” pioneer and British socialist William Morris) was a strong believer in the “roses” part of socialist demand for “bread and roses.” He wanted people to live in economically stable circumstances so they could be freed to let their creativity flourish.

With the abolition of private property, then, we shall have true, beautiful, healthy Individualism. Nobody will waste his life in accumulating things, and the symbols for things. One will live. To live is the rarest thing in the world. Most people exist, that is all.

Wilde was an unabashed utopian, and much of the essay seems impractical and naive today. But I think it’s hard to deny that Wilde’s text poses a serious challenge to the views of those who see “socialism” as a form of “collectivism” that denies “individual freedom.” For Wilde, individual freedom was everything, which is why he didn’t want the concentration of economic power in the hands of capitalists. Wilde is also critical in the essay of the coercive state and the practice of punishment, and he himself was brutalized by the British prison system. His “Ballad of Reading Gaol” holds up to this day as a stirring attack on the practice of imprisonment. Wilde rites:

I know not whether Laws be right,

Or whether Laws be wrong;

All that we know who lie in gaol

Is that the wall is strong;

And that each day is like a year,

A year whose days are long.

But this I know, that every Law

That men have made for Man,

Since first Man took his brother’s life,

And the sad world began,

But straws the wheat and saves the chaff

With a most evil fan.

This too I know—and wise it were

If each could know the same—

That every prison that men build

Is built with bricks of shame,

And bound with bars lest Christ should see

How men their brothers maim.

Malala Yousafzai

Malala Yousafzai is another of those figures who plenty of people celebrate as an icon without really listening to or engaging with. Even as she was being rightly held up as a symbol of resistance to patriarchy, Malala’s radical socialist political convictions were all but ignored in the Western press. And yet she is someone who has said: “I am convinced Socialism is the only answer and I urge all comrades to take this struggle to a victorious conclusion. Only this will free us from the chains of bigotry and exploitation.” As a Socialist Worker article on Malala’s politics explains:

“As much as it highlights Malala’s words on education and nonviolence, the U.S. corporate media never mentions the side of Malala that it doesn’t like, the side of Malala that doesn’t serve but rather challenges Western imperialist interests, the side of Malala that overtly opposes not just U.S. drone strikes but capitalism itself.”

Malala has said plainly she is not a “Western puppet” and is critical of the U.S., having said in 2021 that “It’s the decision of the U.S. and other countries that have led to the situation that the people of Afghanistan are witnessing right now.” But few in the U.S. media are particularly interested in elevating Malala as a critic of this country. She is best presented as a benign figure of women’s global empowerment who makes moral criticisms of the Taliban, but not of us.

George Orwell

I disliked Nineteen Eighty-Four when I first read it, and I don’t really care for it to this day. As I discussed in an essay about it a few years back, I think Orwell just missed some crucial facts about totalitarianism. He depicted a world that was objectively and obviously horrible, without showing why such a world would have appeal for anyone. In reality, the disturbing truth about dystopian societies is that they can be great for some people, and they have a good pitch. I think it’s crucial to understand this if we want to get off the path to dystopia. We have to recognize that for some people, there are compelling reasons why the dystopian world would be appealing.

But while I find Orwell’s most famous books frustrating (not really much of an Animal Farm fan either), I love and treasure George Orwell’s other work, the stuff you’re not assigned in school. Homage to Catalonia, Burmese Days, Down and Out in Paris and London, and The Road to Wigan Pier, plus the essays are overflowing with insight and a hatred of inequality. They are also deeply socialist works. The short passage in Homage in which Orwell pays tribute to revolutionary Barcelona is an inspiring description of what an “alternative society” might actually feel like, and why he took up arms to defend what he saw in Spain:

Every shop and cafe had an inscription saying that it had been collectivized; even the bootblacks had been collectivized and their boxes painted red and black. Waiters and shop-walkers looked you in the face and treated you as an equal. Servile and even ceremonial forms of speech had temporarily disappeared. Nobody said ‘Señior’ or ‘Don’ or even ‘Usted’; everyone called everyone else ‘Comrade’ and ‘Thou’, and said ‘Salud!’ instead of ‘Buenos días.’ Tipping was forbidden by law; almost my first experience was receiving a lecture from a hotel manager for trying to tip a lift-boy. There were no private motor-cars, they had all been commandeered, and all the trams and taxis and much of the other transport were painted red and black. The revolutionary posters were everywhere, flaming from the walls in clean reds and blues that made the few remaining advertisements look like daubs of mud. Down the Ramblas, the wide central artery of the town where crowds of people streamed constantly to and fro, the loudspeakers were bellowing revolutionary songs all day and far into the night. And it was the aspect of the crowds that was the queerest thing of all. In outward appearance it was a town in which the wealthy classes had practically ceased to exist. Except for a small number of women and foreigners there were no ‘well-dressed’ people at all. Practically everyone wore rough working-class clothes, or blue overalls, or some variant of the militia uniform. All this was queer and moving. There was much in it that I did not understand, in some ways I did not even like it, but I recognized it immediately as a state of affairs worth fighting for.

I highly recommend all of Orwell’s nonfiction, most of which holds up decently well. (I particularly like his essay about the authoritarian misery of British boarding school life.) Many on the left (fairly) distrust Orwell because late in his life he committed the unconscionable act of naming suspected communists to the British government.

Honorable Mentions

Plenty of historical figures who would never have described themselves as socialists were nevertheless much more egalitarian and radical than their public image. Jesus believed that “you cannot serve both God and mammon,” and claimed it was easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of Heaven (i.e., not very easy at all). Christian socialism and liberation theology are honorable traditions that take Jesus’ belief in nonviolence and mercy seriously.

There are plenty of figures whose “radical sides” it took me far too long to discover. I wish I’d read Leo Tolstoy’s profound Christian anarchist work The Kingdom of God is Within You many years earlier. Thomas Paine, as historian Harvey Kaye has long documented, was an early exponent of social democratic policies, not just the author of a famous anti-monarchist tract. In political philosophy classes in college, I was taught the views of the famous philosopher John Rawls, who was presented to me as a liberal who rationalized certain kinds of inequality. In fact, he came to far more socialistic conclusions than I understood. John Stuart Mill, too, was presented to me as essentially a libertarian, but when I read his Principles of Political Economy for myself, I found that the passages on socialism were distinctly favorable. (Likewise, Adam Smith of “invisible hand” fame was, as Noam Chomsky has long pointed out, much less of a proponent of free market capitalism than he is popularly seen as.)

So there are plenty of those who are known for one thing (e.g. Paine’s Common Sense) but have the parts of their work that pose a deeper, lasting challenge to the economic status quo ignored. Of course, there are other historical figures who are simply ignored altogether. I’ve written about a few more of those here (including the great early Black socialists Peter Clark and Hubert Harrison). One thing that decades of reading has taught me is that history is full of fascinating figures who should have been remembered but haven’t been. And nobody is going to tell you about many of them; you have to go out with a curious mind and find them yourself. But it’s worth it, because when you discover the words of some long-dead person who dealt with the same problems you do, and who fought the same fights, you feel your own strength growing, because it is like meeting a new friend or comrade who is beside you in tough times.

_(20145706174)%20(1).jpg?width=352&name=Berea_College_20101122_FoodService_LK(23)_(20145706174)%20(1).jpg)