Why We Should Abolish the Family

The family is a conservative project that limits human flourishing. The family must be abolished.

“The principle underlying capitalistic society and the principle of love are incompatible.”

Erich Fromm, The Art of Loving, 1956

“I think that a revolution—a socialist revolution—will break down the family structure as we know it now. The woman, being freed from her menial position, either as the lowest-paid worker or as household slave, will be out of the home more. … The concept of marriage will change, because marriage right now is a kind of slave contract. … Probably, in the future, marriage itself, as a contract, will not exist. … People will have the freedom to relate to each other as humans, to enjoy each other intellectually, sexually, and whatever else. I don’t see where there are any great advantages to the nuclear family at this point.”

Denise Oliver, Palante: Voices and Photographs of the Young Lords, 1969-1971

My sister and I grew up in the shadow of our parents’ divorce. The failure of that marriage, and the resulting financial impact, was our life’s lesson. We understood that we’d come from a “broken” family. The message was clear: don’t let divorce happen to you.

We came of age in the ’80s and ’90s: Nancy Reagan’s Just Say No to drugs and family values rhetoric, Bill Clinton’s welfare reform and the “defense of marriage.” Clinton’s “end of welfare as we know it” promoted work and marriage as a solution to poverty (as Sarah Jaffe has noted, the preamble of the 1996 law included “Marriage is the foundation of a successful society”). The Defense of Marriage Act defined the institution of marriage as a union between a man and a woman and allowed states not to recognize same-sex marriages. By that time, the “endless privatization of everyday life and necessary resources that we call neoliberalism,” as writer Yasmin Nair puts it, had come into force.

My mother relied on our neighbors (themselves housewives) and family members for child care and rides to get us to and from public school while she was at work. Even though my mother had a college degree, she had spent ten years as a housewife and thus had a work gap on her résumé which didn’t help in finding jobs that paid well. We lived, to borrow a phrase Bernie Sanders uses, “paycheck to paycheck.” My mother didn’t get to do things she enjoyed: stargazing, astronomy, bike riding, or even just exercising. Her days were spent at work, and her evenings and weekends caring for children. It never occurred to me as a child to consider the love or care my mother was not getting while my sister and I were loved and cared for and managed to grow up and go off to college. What conservatives would see as a success story, I see as a kind of tragedy. I wish my mother had been, in the words of family abolitionist and writer Sophie Lewis, “less alone, less burdened by caring responsibilities, less trapped.”

As a child, I also understood that my family did not measure up to the family. As professor of gender, sexuality, and feminist studies Kathi Weeks has written, the family, characterized by privatized care, the (heterosexual) couple unit, and biologically related kin, is “legislatively declared, legally defended, and socially prescribed” in the United States. There’s a right way to do family, and a wrong way, as conservatives often tell us.

We all need families—sometimes more than one—in order to survive. In a society built around scarcity—of educational opportunities and jobs, healthcare, housing, and even the prospect of a dignified retirement—a desire for coupledom and family makes sense. As M.E. O’Brien, a writer who focuses on gender freedom and communist theory, puts it, “there’s a strong material logic” to the couple form. “If you find the right person, you’re going to be okay.” But beyond material considerations, even wealthy pop stars want the one and the family. John Mayer, the singer-songwriter and guitarist who rose to fame in the early 2000s, has been singing about serial monogamy for over 20 years and makes clear in his music (and in interviews) that he wants to get married and have children, a house, and a “home life” (things that have eluded him thus far). Pop star Adele has admitted that she was “obsessed with the nuclear family my whole life because I never came from one.” She got divorced a few years ago—“I was just embarrassed I didn’t make my marriage work”—and said in an interview with Mayer that marriage had given her the “safest” feeling she’d ever had.

The social psychologist Erich Fromm wrote in his 1956 book The Art of Loving that “In the United States … to a vast extent, people are in search of ‘romantic love,’ of the personal experience of love that should lead to marriage.” But, according to Fromm, capitalist societies had commodified human relations, particularly the search for spouses, to the detriment of humans. He wrote about the marriage “market” of his time, in which people looked for the best “deal” of “personality packages.” We now have online dating, which ultimately turns dating into a market (you must pay for access to that market) where people and their profiles are like items on a menu to choose from. For Fromm, love was a way of being, an orientation, not primarily an attachment to another person or the possession of a certain status (a marriage and family). And yet, he argued, we spend so much time searching for someone to love rather than cultivating the art of loving as a practice involving “the active concern for the life and the growth of that which we love.”

What this has to do with the family is that we have substituted rigid notions of family structure (and “family values”) for the practice of loving. What is “the family” but a set of norms around gender, sexuality, household labor, and the pooling of resources for economic survival? We only need the family because our society is organized in such a way as to make atomized families the main unit responsible for our survival in an increasingly unequal society with limited social safety nets. Yet, marriage and the nuclear family are but one way we human beings can organize ourselves. They are not inevitable, universal, or timeless despite all the cultural and political signals we get that suggest they are.1

To critique the family, then, is to level a critique of the conditions of a capitalist society that makes the nuclear family our main source of support and survival and that uses the family as a weapon to discipline or stigmatize those that don’t comply with traditional family structures or norms around gender and sexuality. In this sense, the family is, in O’Brien’s words, an “obstacle to human freedom.” The family must be abolished, which means a “breaking open of the family to free and unleash what’s good in it and to generalize that into the social body as a whole. To make the necessary forms of care available to everyone unconditionally.”

As Nair has argued:

“We, culture at large and/or the state, need to recognize different forms of relationships. By that, we don’t mean to be prescriptive about what creates a family but to demand that the state not determine whether we live or die based on what kinds of families or kinship groups we inhabit.”

Everyone can support family abolition, even those who feel there is nothing wrong with their family. Family abolition is not about breaking up individual families but about radically changing the society that makes the family structure necessary, about creating a society in which everyone is cared for. We can—and must—imagine and create better ways to live and to love each other.

We are often told by conservatives that the traditional family is the bedrock of a moral society. As Sarah Jones writes in Dissent,

“Marriage is a conservative institution, a way for class to reproduce itself. It is the foundation for the little platoons—family, church, and community. … To conservatives, marriage will cure poverty and childhood trauma and gun violence. But they long specifically for so-called traditional families, with a breadwinning father and a stay-at-home mother.”

Take this “family values” passage from the 1976 Republican Party platform:

“Families must continue to be the foundation of our nation. Families—not government programs—are the best way to make sure our children are properly nurtured, our elderly are cared for, our cultural and spiritual heritages are perpetuated, our laws are observed and our values are preserved. … [I]t is imperative that our government’s programs, actions, officials, and social welfare institutions must never be allowed to jeopardize the family. We fear the government may be powerful enough to destroy our families; we know that it is not powerful enough to replace them.”

The platform goes on to explain how the tax code, the estate tax (to “minimize disruption of already bereaved families”), and welfare stipulations encouraging marriage were to be designed with the preservation of the family in mind. Government policies still confer financial benefits to married people compared to singles. From 2001- 2014 the federal government spent nearly $800 million on marriage promotion programs, often targeting poor people of color for relationship counseling. These programs have been largely ineffective in achieving stated goals. As recently as 2021, the government maintained Healthy Marriage and Responsible Fatherhood program funding; its website claims that children do best when raised by two married biological parents, a longtime claim of social conservatives which has been refuted by recent research and which ignores the fact that many cultures practice communal child rearing, also called alloparenting. Despite such public policy, marriage rates in the U.S. are now at a 20-year low.

The right-wing, Christian family values agenda picked up influence in the 1970s, according to historian Anthea Butler. In White Evangelical Racism: The Politics of Morality in America, Butler explains how the Moral Majority, formed in 1979 by evangelical leaders, “explicitly teamed with Republican Party politics and political action” to “re-create this great nation” according to white, Christian standards. Around the sametime, offshoot organizations such as American Family Association, Focus on the Family, and the Family Research Council “began lobbying government on evangelical concerns about the family, marriage, abortion, and education.” An “underlying message of these groups,” she argues, was that “sexual immorality, including race mixing, would be its [America’s] downfall.” Butler also argues that evangelicalism is no longer simply a religious movement but rather a “nationalistic political movement whose purpose is to support the hegemony of white Christian men over and against the flourishing of others.” Evangelicals tend to vote in large numbers for right-wing politicians, including Donald J. Trump, who, as an accused sexual predator who has endorsed calling his daughter Ivanka a “piece of ass,” represents the opposite of “family values.”

The 1976 platform seems quaint compared to GOP Florida Sen. Rick Scott’s chilling manifesto, “An 11 Point Plan to Rescue America,” released earlier this year. Decrying the “militant left’s” plan to “change or destroy” things like “the nuclear family, gender, [and] traditional morality,” Scott elaborates:

“We will protect, defend, and promote the American Family at all costs. The nuclear family is crucial to civilization, it is God’s design for humanity, and it must be protected and celebrated. To say otherwise is to deny science.”

While Republicans are the most rabidly in favor of the heterosexual marriage-based family, both Republicans and Democrats use rhetoric around the family to appeal to voters, sometimes as part of the ongoing “culture wars.” Conservatives invoke family values to oppose everything from abortion, feminism, pornography, comprehensive sex education, and divorce to homosexuality, rights for trans people, same-sex marriage, critical race theory, and Black Lives Matter. Democrats often refer to families in the context of work: “working families,” a phrase frequently used by Bernie Sanders, or, as noted in the 2020 DNC platform: “Enacting Robust Work-Family Policies,” in which the Democrats claim to support 12 weeks of paid family and medical leave “for all workers and family units.” (Not only have the Democrats failed to pass such a policy, we’re left to wonder what a “family unit” is defined as.) As Lewis has argued, “to attack the family is … unthinkable” in our current politics. “Nowhere on the party-political spectrum can one find proposals to dethrone the family, hasten its demise, or even decenter it in policy.”

While conservatives are preoccupied with the family as a force for moral good, they are not as attentive to the ways in which the family harms people. As Lewis pointed out, feminist writer Madeline Lane-McKinley predicted early in 2020 that the pandemic would expose the dark underbelly of family and home life:

“Households are capitalism’s pressure cookers. This crisis will see a surge in housework—cleaning, cooking, caretaking, but also child abuse, molestation, intimate partner rape, psychological torture, and more. Not a time to forget to abolish the family.”

Indeed, there has been a significant rise in domestic violence worldwide since the start of the pandemic. Lewis has pointed out that the “vast majority of queerphobic and sexualized violence” takes place within the family. According to a 2019 Congressional Research Service report on homeless youth, LGBTQ youth face increased risk of homelessness, often because they are forced out of their homes due to negative reactions from family when they come out. As journalist Rachel Louise Snyder wrote in her 2019 book No Visible Bruises: What We Don’t Know About Domestic Violence Can Kill Us, domestic violence is responsible for 50 percent of cases of homelessness for women and is the third leading cause of homelessness in the U.S. Thus, Snyder writes, the “private violence” within families has “vastly public consequences.”

For many, family violence often has lasting effects. Sociologist Jennifer M. Silva interviewed 100 young working class adults (defined as adults whose fathers had not obtained a bachelor’s degree) for her 2013 book Coming up Short: Working-Class Adulthood in an Age of Uncertainty. Silva noted that for many of the respondents in her book, “hurtful and agonizing betrayals within the family lie at the root” of their personal “demons.” The adults in Silva’s cohort spent tremendous amounts of energy, sometimes unsuccessfully, trying to heal themselves from their family traumas.

As Nicole Sussner Rodgers and Julie Kohler write in The Nation, for the Right, “the battle may be about the uterus, but the war is for the future of the family.” Indeed, we are often told that the traditional family is in crisis. David Brooks’ 2020 Atlantic article, “The Nuclear Family was a Mistake,” argues that a lack of extended family (he laments the rise of single-parent and “chaotic” families) has increased inequality in our society. Popular books by academics also note the decline of the traditional family, or a family values-based “way of life,” arguing that non-traditional family structures are implicated in troubling social phenomena such as inequality and deaths of despair. Sociologist Robert D. Putman describes the “opportunity gap” between children born to parents with and without a college degree in his 2015 book Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis, noting different family structures (among other characteristics) between the educated and uneducated. Economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton describe deaths from suicide, alcoholism, and drug overdoses among the white working class in their 2020 book Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism. Case and Deaton come to ominous conclusions. A lack of family values can be, in their view, an important part of a pathway to despair. And while the authors admit that the impacts of lifestyle choices do not have easily quantifiable values, the book’s heavy moralizing on such matters (for instance, the error unmarried women make in having children) is hard to ignore; the effect is to de-emphasize the importance of systemic policies that can be legislated, such as improved wages and working conditions, universal health care, free college, public housing, and universal child care and pre-K.

Conservatives are right that the family is in crisis—to the extent that “crisis” means that the structures of peoples’ lives (their marital status, their living arrangements, their decisions regarding reproduction) often reflect their overall level of economic security (or lack thereof ). The traditional family has become unattainable for many, especially the working class. As Silva writes:

Traditional markers of adulthood—leaving home, completing school, establishing financial independence, marriage, and childbearing—have become strikingly delayed or even foregone in the latter half of the twentieth century, particularly for the working class.”

She notes that the majority of her respondents dealt with unstable and low-paying service jobs, credit card debt, family dissolution, and “illness and work-related disabilities, domestic violence, and constant financial stress.” In her study sample, respondents were haunted by an idealized working-class life of the past: of marriage, gendered norms (male breadwinner, female homemaker), home ownership, and having children. But for most, the overall instability of their lives precluded any chance of achieving this kind of life. This is a point that Putnam also concedes: “Unemployment, underemployment, and poor economic prospects discourage and undermine stable relationships—that is the nearly universal finding of many studies, both qualitative and quantitative,” he writes in Our Kids.

The family is in crisis, yet the family is so traditional. How can it be both?

The story of the traditional family is, like most myths, a mixture of truth and fantasy. As marriage historian Stephanie Coontz writes in The Way We Never Were: American Families and the Nostalgia Trap, “Like most visions of a ‘golden age,’ the ‘traditional family’ … evaporates on closer examination. It is an ahistorical amalgam of structures, values, and behaviors that never coexisted in the same time and place.” Nonetheless, what we think of as the traditional family with heterosexual couple, male breadwinner, female housewife, and children became possible due to the convergence of multiple factors in the early and mid 20th century.

The workers’ movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, bolstered by unions, led to improved wages; the male breadwinner family was promoted as a desirable feature of (white) working-class life. The Depression era saw a “disruption of the family,” as massive unemployment and destitution led to homelessness. People sought refuge in shantytowns called Hoovervilles or moved in with others when possible. Children were unable to attend school; women turned to sex work; there was the sense that the family was “broken.” The New Deal response led the state to be more actively involved in the family, as this was the period which gave us Social Security and Aid to Dependent Children, among other programs. In Work Won’t Love You Back, Sarah Jaffe writes that the New Deal period in the U.S.

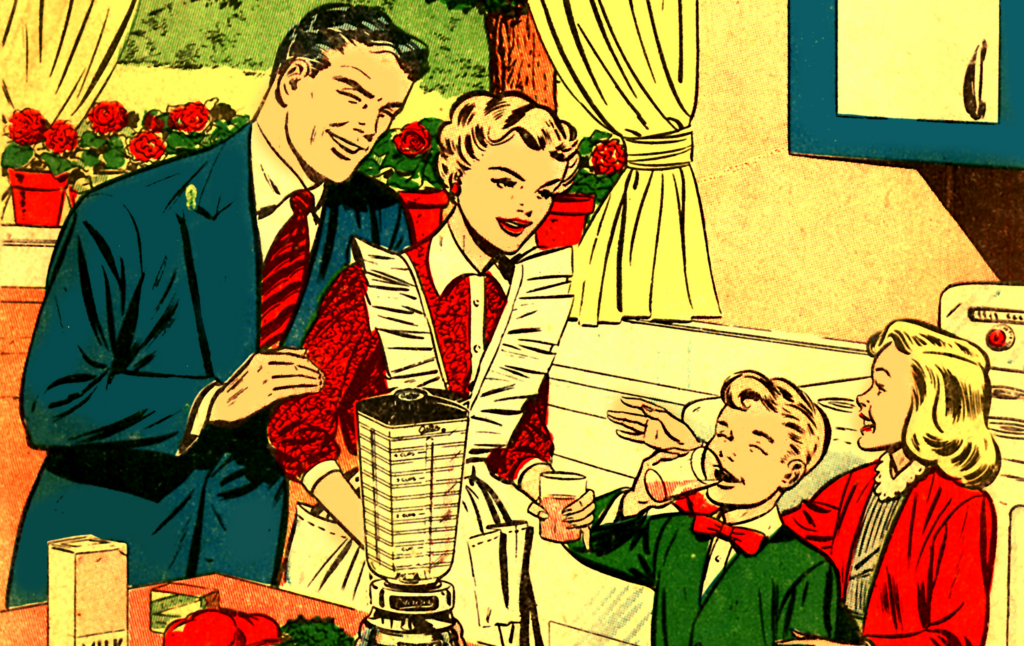

“gave us the thing we think of as the ‘traditional’ family: the suburban two point five-kid picket-fence white nuclear household, June Cleaver mom at home making dinner in high heels and waiting for her husband to come home from his eight-hour day in his five-day workweek.”

Putnam notes that around the mid-20th century, the male breadwinner nuclear family became common.

But since the ’70s, a number of changes (including the stagnation or decrease of working-class wages and the shifting of gender roles, with women entering the workforce and obtaining higher education) have brought about the collapse of the family and a diversification of structures. O’Brien writes:

“The male-breadwinner family form is no longer characteristic of any sector of society, and has lost its social hegemony due to the convergence of several simultaneous trends. In its place, we’ve seen the dramatic and steady growth of dual-wage earner households, of people choosing not to partner or marry, of atomized and fragmented family structures. … These dynamics have produced a heterogeneous array of family forms in working-class life.”

In Our Kids, Putnam describes what he calls a “two-tier” family system of the U.S., which he says has predominated for the last 30 or so years (recall that the book was written in 2015). He breaks up society broadly into thirds: upper third is college educated, middle third has some post-secondary education, and bottom third has no more than a high school diploma. For the upper third, college-educated of society, there’s the “neo-traditional” model in which the educated tend to marry each other and both spouses work; these families can afford to pay for labor and childcare that was traditionally carried out by a housewife. For the lower third of society, there are “blended families,” in which adults tend not to marry and tend to have children with multiple partners, sometimes called “fragile families,” a phrase Putnam attributes to the late sociologist Sara McLanahan. Much is made of these structures and how the children of the neo-traditional model enjoy better life outcomes than those unfortunate to be raised in the lower model. Putnam is careful to acknowledge that correlation is not causation. But there is an underlying assumption in his book: namely, that if we could make the lower third more like the upper third, more children could do better in life. The tendency is to think of family structure as something that needs fixing instead of simply giving care to everyone. (When I read about researchers discovering things that tend to be correlated with good outcomes for people—multiple parental incomes, education, stable housing, and so forth—I wonder why the argument isn’t just to give people those things. It’s like seeing someone floundering in water and refusing to throw them a life jacket or buoy.)

Rather than think of the collapse of the traditional family as a sign of moral degeneration of the citizenry, though, we ought to think of it as the inevitable fate of an institution that was never natural or stable to begin with.

Academic and political commentator Irami Osei-Frimpong recently argued (in the context of the Supreme Court leak about overturning Roe v. Wade) that much of the U.S. culture wars, including the question of abortion, boils down to a question of “Who Gets to Have Sex?” and under what conditions. The “who” can refer to race, gender, sexual orientation, class, or employment or marital status. The conditions can refer to what sex is for: Pleasure? Procreation? Exchange of money? Something else? The typical narrative on the Right is that heterosexual, marriage-based, procreative sex is legitimate, and behavior different from this is to be dismissed (and even outlawed) as an abomination. Sen. Rick Scott claims this narrative is based on science. But he is mixing value judgments with scientific facts. Science provides tools and observations we can use to understand the world but doesn’t constitute a value system for those observations.

Scott claims that science is the basis of the family as “God’s design for humanity” and that science dictates strict gender binaries of male and female (implied as the basis of the pair bond). “Facts are facts, the earth is round, the sun is hot, there are two genders … to say otherwise is to deny science.” When Scott conflates his values with other documented facts about the universe, he isn’t just co-opting the vocabulary of liberal wokeness (“Listen to the scientists,” per President Biden). His argument goes much deeper. He’s promoting the family almost as if it were human nature.2

A simple consideration of other cultures different from our own provides examples of human behavior that do not adhere to Scott’s story about the purpose of sex and marriage. One example comes from David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. In the book, Graeber cited anthropological observations of barter ceremonies between groups of neighboring people. In Australia, the Gunwinggu people were noted to carry out a barter ceremony called dzamalag. These elaborate rituals—the one Graeber cited happened in the 1940s—involved singing, dancing, and sex between members of the different groups, even individuals who were noted to be married. (Their idea of “marriage” must have been different from our own.) The Mosuo people in China, as another example, are a matriarchal society in which women have a great degree of sexual freedom:

“Men and women practise what is known as a ‘walking marriage’—an elegant term for what are essentially furtive, nocturnal hook-ups with lovers known as ‘axia.’ A man’s hat hung on the door handle of a woman’s quarters is a sign to other men not to enter. These range from one-night stands to regular encounters that deepen into exclusive, life-long partnerships—and may or may not end in pregnancy. But couples never live together, and no one says, ‘I do.’”

Also consider that in Islam, the second most practiced faith in the world, there exists a temporary marriage of varying lengths called a mutʿah. While it is not practiced uniformly and has been likened by some within the faith to a form of prostitution because it involves the payment of money to the woman, the fact that this arrangement could be considered legitimate reveals how arbitrary (and culturally determined) our sexual mores can be. Just as we can observe a range of sexual and social behaviors among humans, sanctioned (or not) by religion or culture, it turns out that the U.S family as we know it also arose from specific historical conditions.

The Family as a Weapon

The nuclear family as promoted by the state has been imposed upon non-white and immigrant populations since colonial times. Consider the case of Native Americans. As Stephanie Coontz explains in The Way We Never Were, colonialists

“forced Native American extended families off their collective property and onto single-family plots. They made Indian men the public representatives of families, ignoring the traditional role of women in community leadership, and placed Indian children in boarding schools to eradicate traditional Native American values.”

Discoveries of mass graves at sites of these boarding schools reveal just one aspect of the larger genocide of Native people (survivors also recall rampant sexual abuse by Catholic officials at these religious schools).

Professor of Native studies Kim TallBear explains further that “settler sexuality” rested on notions of binary sexes, hetero-normativity, and sexual monogamy. Quoting Cree-Métis feminist Kim Anderson in Making Kin Not Population, TallBear writes,

“‘One of the biggest targets of colonialism was the Indigenous family’ in which women had occupied positions of authority and controlled property. The colonial state targeted women’s power, tying land tenure rights to heterosexual, one-on-one, lifelong marriages, thus tying women’s economic well being to men who legally controlled the property. Indeed, women themselves became property.”

TallBear describes Native genders and sexual relationships as more fluid than that of the settlers—especially the rigid notion of monogamy, which she says can be considered a form of “hoarding” another person’s body. Caretaking and domestic duties, she notes, were also carried out more diffusely, among “extended kinship” relationships. Thus, the idea of a “single mother” is nonsensical.

African American families have faced family-related oppression since the days of slavery. Most obviously, kidnapping African people to work in bondage was a form of destruction to those societies; slave families were routinely separated at the auction block. Once freed from slavery, Black people were forced into tenant sharecropping under the white backlash to Reconstruction which gave us Jim Crow. Sharecropping conditions favored marriage; at the same time, the workers’ movement gains of the early 20th century were denied to Black people; the New Deal also excluded domestic and agricultural workers, sectors where Black workers were concentrated. Thus, the male-breadwinner wage was largely inaccessible to Black men and families.

The Black family has been and continues to be pathologized and directly targeted by policy. The oft-mentioned Moynihan Report of 1965 (The Negro Family: The Case for National Action), which blamed Black mothers for the “disintegration of the Black family” and linked Black family demise to the urban unrest of the period, was used to justify the burgeoning “war on crime” that targeted neighborhoods of color. In Our Kids, Putnam admits that there are three policy choices that “probably did contribute to [the] family breakdown” that his book is concerned with: the war on drugs, “three strikes” sentencing, and the sharp increase in incarceration. This is a profound admission that I wish intellectuals across the political spectrum—conservatives in particular—would engage with. To acknowledge that “law and order” policies, which are accepted by liberals and conservatives alike, are deleterious to families would be quite an admission indeed.

For a society so concerned about the family, the U.S. has traumatized the most vulnerable members of the family—children—as a matter of official policy. As professor of law and sociology Dorothy Roberts has written:

“Since its inception, the United States has wielded child removal to terrorize, control, and disintegrate racialized population: enslaved African families, emancipated Black children held captive as apprentices by their former enslavers, Indigenous children kidnapped and confined to boarding schools under a federal campaign of tribal decimation, and European immigrant children swept up from urban slums by elite charities and put to work on distant farms.”

Finally, the state of U.S. children needs to be mentioned. Our child poverty rate is higher than many peer nations; social mobility has decreased; more than 140,000 U.S. children have been orphaned due to loss of caregivers from COVID; and a shortage of infant formula drags on (Pete Buttigieg matter-of-factly said that our “capitalist” economy doesn’t make baby formula). Finally, the cruel family separations at the U.S.-Mexico border are also a reminder that the integrity of those families does not matter to the state. The U.S. does not seem to act like a society that cares enough about all children and their families.

Leftist Demands for Family Abolition

In “To Abolish the Family: The Working-Class Family and Gender Liberation in Capitalist Development,” O’Brien explains that the Left has long critiqued the traditional family, from Marx and Engels, who saw the family as a key part of the bourgeois social and economic order (particularly via inheritance), to 19th century utopian socialists and the anti-capitalist feminists and queer radicals of the 1970s. Central to the leftist critique is the fact that the family is an institution that has been critical to the functioning of capitalism. Workers have to be fed, clothed, housed, and taken care of, and the household is the site where this care (and sexual reproduction, or the creation of new workers) takes place. Labor is gendered in the household, with women often doing unpaid work. The family also enables people who don’t or can’t work—infants and children, the elderly, and the disabled and unemployed—to receive care. The family is where we are supposed to get all the emotional and physical care we need. The family is where we are made dependent on a wage laborer—and disciplined in terms of gender roles and expression.

While liberal feminists wanted women to get out of the house and to secure equality in the workplace, radical feminists saw husbands as bosses in their own right. Radicals of the late ’60s and ’70s “sought the abolition of the male-breadwinner, heterosexual nuclear family form as a means towards full sexual and gender freedom.” But over time, feminists began to favor diversity of family form, which “remains the dominant feminist approach to the politics of the family since the 1990s,” writes Weeks. Yet diversification and representation—making capitalist institutions (marriage, the military, politics) more friendly and inclusive to racial and ethnic minorities, LGBTQ people, or others who have been marginalized—are not radical. A radical leftist vision is one that seeks to dismantle or transform these institutions entirely, including the family.

As Weeks points out, popular leftist policy proposals around health insurance and wages could decrease our dependence on the family structure. These policies would compensate for injustices exacerbated by the family or obviate the need for the family altogether: policies like Medicare for All, free college and student debt cancellation, universal basic income (UBI), and a $25 minimum wage, just to name a few. With Medicare for All, healthcare benefits would not be tied to marital status; young people wouldn’t get kicked off their parents’ insurance at a certain age. With free college, there’s no need to take on mountains of debt to get a college degree, or to depend on parents who might be unwilling or unable to fill out financial aid forms or contribute to the cost of education. With UBI and higher wages, people do not have to stay dependent upon other wage earners or the living arrangements sometimes dictated by those relationships. These policies increase human freedom and thus our freedom from the confines of the family structure.

And yet, as Weeks explains, family abolition is more than a series of policies. It’s a “political project” to create an entirely different society in which everyone’s needs are met. In “Communizing Care,” O’Brien describes post-revolutionary, communist arrangements in which people care for each other in larger structures loosely based on the phalansteries conceived of by the utopianist Charles Fourier (the phalansteries were to rescue people from what Fourier saw as the dreadfulness of married life). These are not counterculture communes that exist within capitalism but true post-capitalist structures in which groups of a couple hundred people or so are in charge of taking care of everyone in the group and coordinating with other communes the production and distribution of goods and services that people need to live.

What’s especially notable about O’Brien’s vision of the phalansteries is that there is a concern for everyone’s well-being, sexual needs as collective concerns, as well as attention and sensitivity to vulnerable people, to “biological variation … [what] we now define as disability, neurodivergence, or mental illness.” While people would be free to form their own kinship units, including with biological relatives, the family as it is known would not form any kind of “economic unit” as in current life. We can imagine communal parenting, freedom of expression for sexuality and gender, and relationships not based on economic coercion.

The roots of such structures can be seen in the caring communities that pop up in protest movements such as Occupy Wall Street in 2011 or Standing Rock, the Indigenous-led protest movement against the Dakota Access Pipeline, or DAPL, north of the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, in 2016. (O’Brien describes such protest kitchens as part of insurrections as key features of family abolition.) In Our History is the Future, Native writer Nick Estes describes camp life at the site of #NoDAPL:

“The main camp was a fully functioning city. There was no running water, but the Cannon Ball Community Center opened its doors for showers. There was no electricity, but Prairie Knights Casino, the tribal casino two miles up the road, had Wi-Fi. And there were no flushable toilets, but Standing Rock paid for porta potties. Where physical infrastructure lacked, an infrastructure of Indigenous resistance and caretaking of relations proliferated—of living and being in community according to Indigenous values—which for the most part kept people safe and warm. … The main kitchen served three hot meals a day. (At its height there were about thirteen free camp kitchens and a half dozen medic tents.) … Elders and children ate first, following a meal prayer. If there were guests … they ate first. The donations tent was well stocked with sleeping bags, blankets, tents, socks, gloves, hats, boots, and so forth. … Everyone was fed and clothed. Everyone had a place. At camp check-in, bodies were needed to cook, dig compost holes, chop wood, take care of children, give rides to Walmart, among other tasks. Many quit their jobs, instead making it their full-time work to cook and to keep others warm and safe.”

The camp included a day school for children as well as direct action training. (And to be clear, family abolition is not about idealizing makeshift camp structures of survival or about making our living conditions less comfortable than we might imagine. The camps illustrate the how and the why of family abolition, not the end goals for the material circumstances of our lives.)

In August 2020, the Intercepted podcast “Escape from the Nuclear Family” featured a story about a group of people weathering the pandemic in Oakland, California. Four families had lived together for 15 years in a “democratic community with friends.” They talked about how their communal life enabled them to deal with the stress of the pandemic.

“It’s a lifesaver, you know, to have other people you know and trust and who care about you and care about your children being a part of your life. We need each other to be our best selves because it’s not as simple as an act of will. And so having that extra support around parenting and even just coordinating … knowing that there’s always people around and that my kids feel comfortable and safe. That’s hugely important and it creates an enormous amount of resilience in our ability to navigate disturbances, whether they’re small or big.”

A policy change we can make now is to build public housing designed with social interactions in mind instead of more unaffordable single-family homes.

Transitioning from isolated units to communal living environments will be challenging; humans are complex and conflict-prone. A post-nuclear family society does not portend freedom from conflict or bad behavior; people could still harm each other. But it does mean people have the opportunity to change their surroundings if their relationships are not working out and would have more support instead of isolation within an abusive environment. The goal is also freedom from the economic constraints under capitalism that make conflict and violence a routine part of human interactions, whether within families or on the streets or in our jobs.

Humans are social creatures, and we evolved to cooperate with others for our survival. We face an epidemic of loneliness and deaths of despair in our society. As people who make it to old age live longer, we will need more care, not less. We need more community and more support, not less.

We also need the state to stop tying people’s relationship choices to taxes and to stop promoting one way (marriage) to bond with another person.

As Fromm concluded in The Art of Loving, “important and radical changes in our social structure are necessary if love is to become a social and not a highly individualistic, marginal phenomena.” This meant that “the economic machine must serve” man “rather than he serve it.”

Family Abolition as an Expansion of Love

In today’s language of the family, we’re to have it all: work-life balance. We’re to work full time and (if we can afford it) hire other women to clean the house, do laundry, and care for children or other family members. As many on the Left have pointed out, society will pay people (often women, and often not much) to take care of children or the elderly—as long as those children and elderly are somebody else’s family members. In reality, society should collectively pay for the care of people of all ages no matter who does the caring. Perhaps the most important point of family abolition is the idea of creating a society rooted in love for everyone, not just one’s genetic kin. To love everyone means to be actively concerned with their care and growth, as Fromm put it. We should want care for everyone. As Lewis argues:

“When you love someone, it simply makes no sense to endorse a social technology that isolates them; privatizes their lifeworld, arbitrarily assigns their dwelling-place, class, and very identity in law; and drastically circumscribes their sphere of intimate, interdependent ties.”

The institution of the family—and those who defend it—continues to limit our freedom, as current developments around gender, reproduction, and sexuality show. The federal right to an abortion has been overturned, and we are in the midst of a moral panic as the right promotes false narratives about drag queens and transgender people as sexual predators.

As Robin D. G. Kelley explains in Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination, freedom and love are revolutionary ideas, and we need both to imagine a better world. To imagine a society free from the oppression of the family, we need to imagine an expansion of love, not a contraction of it. An inclusivity of love for everyone, not the stifling exclusivity imposed by the family.

While not without controversy (a discussion of the authors’ scientific claims in the realm of evolutionary biology and psychology is beyond the scope of this piece), the book Sex at Dawn by Christopher Ryan and Cacilda Jethá got me thinking a lot about how human sexual behavior and relationships can be culturally mediated. They mention the Mosuo people, which I bring up in a later section of this piece, in their book. ↩

As O’Brien points out, even Friedrich Engels, while pointing out the problems of the bourgeois family, saw the normal state of human love as essentially monogamous in nature. ↩