We Can Build Paradises For The Public

We need to recover the concepts of great public goods, public services, and public works. The New Deal’s WPA provides a vision of what is possible.

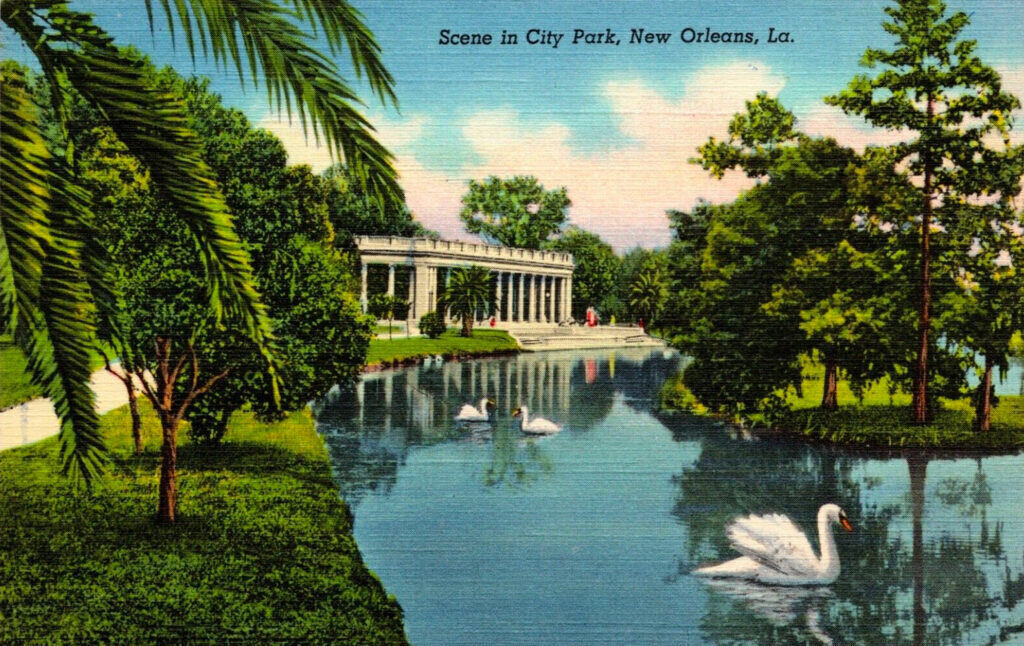

City Park in New Orleans is, to my mind, about as close to paradise as you can get on Earth. Fifty percent bigger than New York’s Central Park (suck it, NYC), it is a sprawling oasis full of live oaks and canopies of moss. You can find almost anything somewhere in its 1300 acres: bike trails, mini golf, a roller coaster, swan boats, actual swans, a botanical garden, a sculpture garden, an art museum, tennis courts, soccer fields, an antique carousel, a kids’ park that recreates various fairy tales, a ferris wheel, a dog park, a little train that goes round, and hot beignets morning, noon, and night. The park is full of people enjoying themselves, playing frisbee, having picnics, or doing outdoor yoga, or attending the “annual fish rodeo, barbecue contest, symphony concert, and music festival.” It is apparently home to “the largest stand of mature live oak trees in the world.”

I try to bike up to City Park at least once a week, because I find that I cannot be unhappy while I am there. It is a place of pure tranquility and joy. Even though I’ve been there hundreds of times, it was only on my most recent visit that I noticed some words carved into one of the main roads: “BUILT BY WORKS PROGRESS ADMINISTRATION, 1937-1939.”

Indeed, when you start to look closely at City Park, the signature of the Roosevelt administrations is everywhere:

In fact, much of the infrastructure that makes City Park such an extraordinary public place was built in the 1930s by the WPA, including bridges and roads but also sculptures and gardens. The WPA transformed the park from what it was:

When the WPA … came to the park it became a different place—workers restored, renovated, improved, and added new buildings, bridges, and roads. Most of the existing brick buildings and art deco sculpture, reliefs, and flourishes on buildings, bridges, and fountains was done by WPA artists and workers who also added new gates, lagoons, benches, shelters, an administration building, 8 roads, 8 bridges, baseball fields, golf clubhouse additions and new courses, a driving range, a caddy house, stadiums for football and baseball, athletic fields, and tennis courts with lights for night-play. Renovations, repairs, and improvements were made to Roosevelt Mall, the Rose Garden, the Casino, the Irby Pool, the Peristyle, and sculptures throughout the park. Popp Fountain was completed, 3 bridges rebuilt, City Park Avenue widened, Navarre Road paved, Lelong Avenue repaved, and Anseman Avenue landscaped. The swampy northern extension was drained and the Couturie Forest established. The lagoons were converted into a stream system with new drainage.

Those of us who enjoy City Park today, then, have the New Deal to thank for transforming the place. The WPA’s approach was not just to make the park functional, but to make it a work of true art, with bas-relief sculptures and Art Deco flourishes adorning pieces of functional infrastructure.

Of course, the WPA operated all across the country, and these kinds of transformations took place in many American cities during the brief period of the agency’s existence. You can see many of them on the Living New Deal map. The WPA contributed such iconic places as Los Angeles’ Griffith Observatory and San Antonio’s River Walk. (Also some less-popular places like a set of bizarre-looking giant dinosaur sculptures in Rapid City, South Dakota and the plaza where JFK was shot.) As KCET Los Angeles notes in a wonderful article on the New Deal legacy in Los Angeles,

“Invisibly, to this day, New Deal handiwork affects the lives of every American. … Every time you drive across Los Angeles, or fly in or out of it, or even flush a toilet in it, you can thank FDR, [Harry] Hopkins and the WPA. If you or your family have ever frequented a park here, attended public school here, or if your grandparents survived the Depression here, you owe the WPA big-time.”

The WPA spent billions annually, over 6 percent of the country’s entire GDP, and ended up building or improving a staggering 600,000 miles of roads, 100,000 bridges, 8,000 parks, nearly 20,000 miles of water mains, nearly 25,000 miles of sidewalks, as well as thousands of playgrounds, airport buildings, schools, and hospitals, as well as public “luxuries” like murals, sculptures, and public pools. WPA architecture, as Joseph Maresca shows in WPA Buildings: Architecture and Art of the New Deal, was both forward-looking and beautiful, and projected a sense of confidence in what the government could do for people. It sent a message that it was worth having faith in civic life and that the people could accomplish great things together.

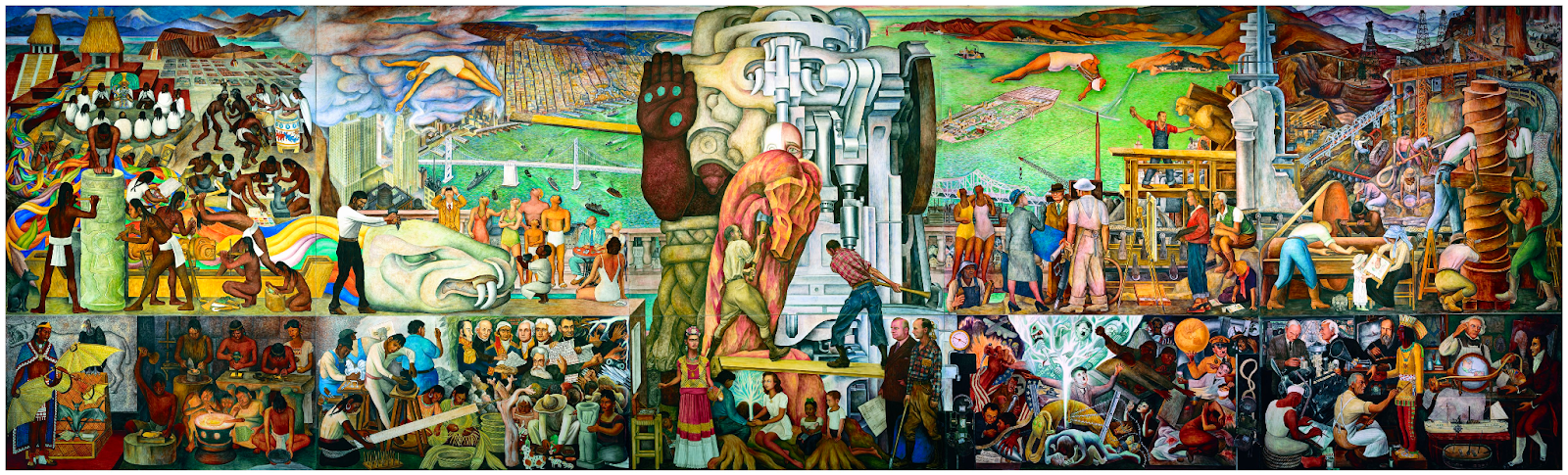

The WPA’s employment of artists, writers, musicians, and performers has become legendary, and it is thanks to the WPA that we have the most comprehensive available oral history interviews with formerly enslaved people. The WPA’s comprehensive travel guides were called by John Steinbeck the “most comprehensive account of the United States” ever produced. (The WPA also had one of the best records on racial inclusivity of the New Deal programs, though it was still imperfect.) The art programs of the New Deal fostered a new kind of cultural democracy.

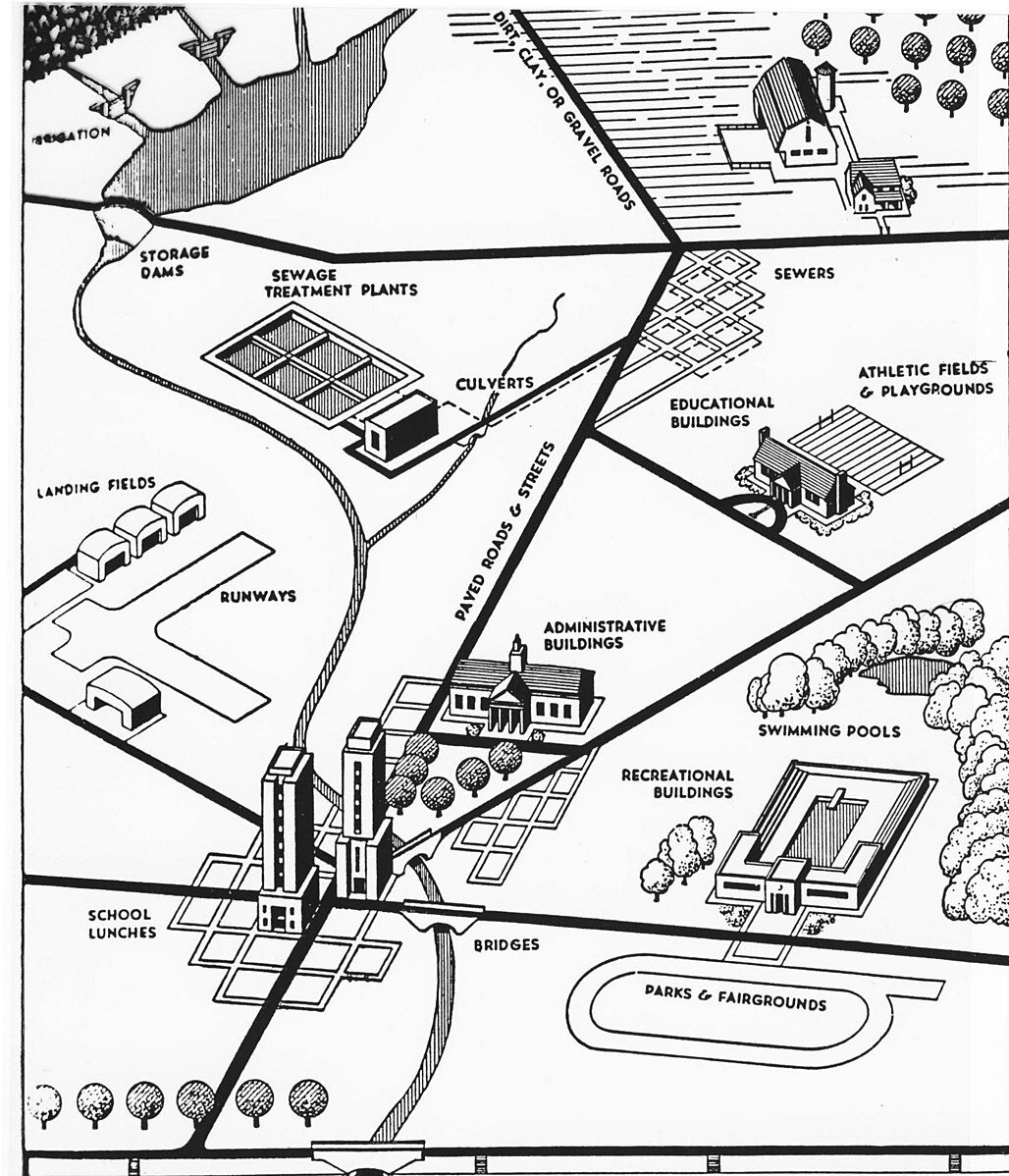

One thing the KCET article on New Deal Los Angeles notes is that while many WPA projects are what we would today call “infrastructure,” Franklin Roosevelt and WPA head Harry Hopkins would not have used this term. They called what the WPA produced “public works.” The terminological distinction is important, because the term “public works,” as Wikipedia notes “does not necessarily carry an economic component.” In other words, infrastructure implies a model whereby the government is producing the foundation on which the economy can function. It’s roads and bridges and sewer lines, and the government builds them in order to help the economy function. Public works are a broader category, as can be seen from this diagram of WPA works:

Is a pool or a sculpture or a fairground “infrastructure”? Probably not, because they are not strictly necessary for the functioning of the economy. But they are public works, things the government builds for the public to use and enjoy.

The WPA was disbanded in the 1940s, because it had been introduced to deal with the problem of unemployment, and World War II solved the American unemployment problem. In retrospect, however, getting rid of the WPA was a tragedy. World War II employed people through an economy of death: the manufacture of planes and bombs to incinerate cities. WPA projects were about improving living conditions, and while the production of such “unnecessary” items as murals and pools might have only been introduced as a way of putting people to work, it is heartbreaking to consider what the country would have been like if the pace of “public works” produced by the WPA had been kept up since 1943. If City Park is as good as it is thanks in large part to what happened between 1937 and 1939, what if we had maintained similar levels of commitment to improving places for the public to enjoy?

City Park is a strange place to be in, in part because it seems to defy a certain economic logic. It is incredibly luxurious but general admission is free, and anyone can go there regardless of their economic class. We are so used to only the rich getting the really nice things, and everyone else getting the bare minimum, if that. City Park shows what it would be like if everyone could have the best. What if the government didn’t just build “infrastructure” like the roads, but actually gave us art and leisure?

I have been thinking lately about how important it is to recover the idea of public services, as well as some of the reasons why public services are important. Take free college and Medicare For All. Much of the conversation about these proposals focuses on the benefit they would provide to those who would use them. The right characterizes this as a handout, a gift of something that people ought rightly to pay for. They do not think there is such a thing as society, or the public. So if we offer free college, “the taxpayer” is funding “your” education, and thus giving you something for free. But when we think more clearly about the complex web of human interactions that we all inhabit, we can see that in fact, there are reasons to provide the service beyond the benefit provided to the direct recipient. A democracy is better managed when its people are well-informed. A city is better off when we make sure that people with serious mental disorders are given free treatment, so they are not roaming the streets in a psychotic state. I am better off when I go to City Park, because I become happier and more relaxed. Then in my interactions with other people, I am more cheerful. We should of course give people things they need out of motives other than self-interest, but public services and public works serve the whole public, not just those who use them directly. When the WPA employed great writers like John Cheever, Ralph Ellison, Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Wright, and Studs Terkel, it was not just helping them but helping all of us by making sure the Great Depression didn’t deprive us of these writers’ work.

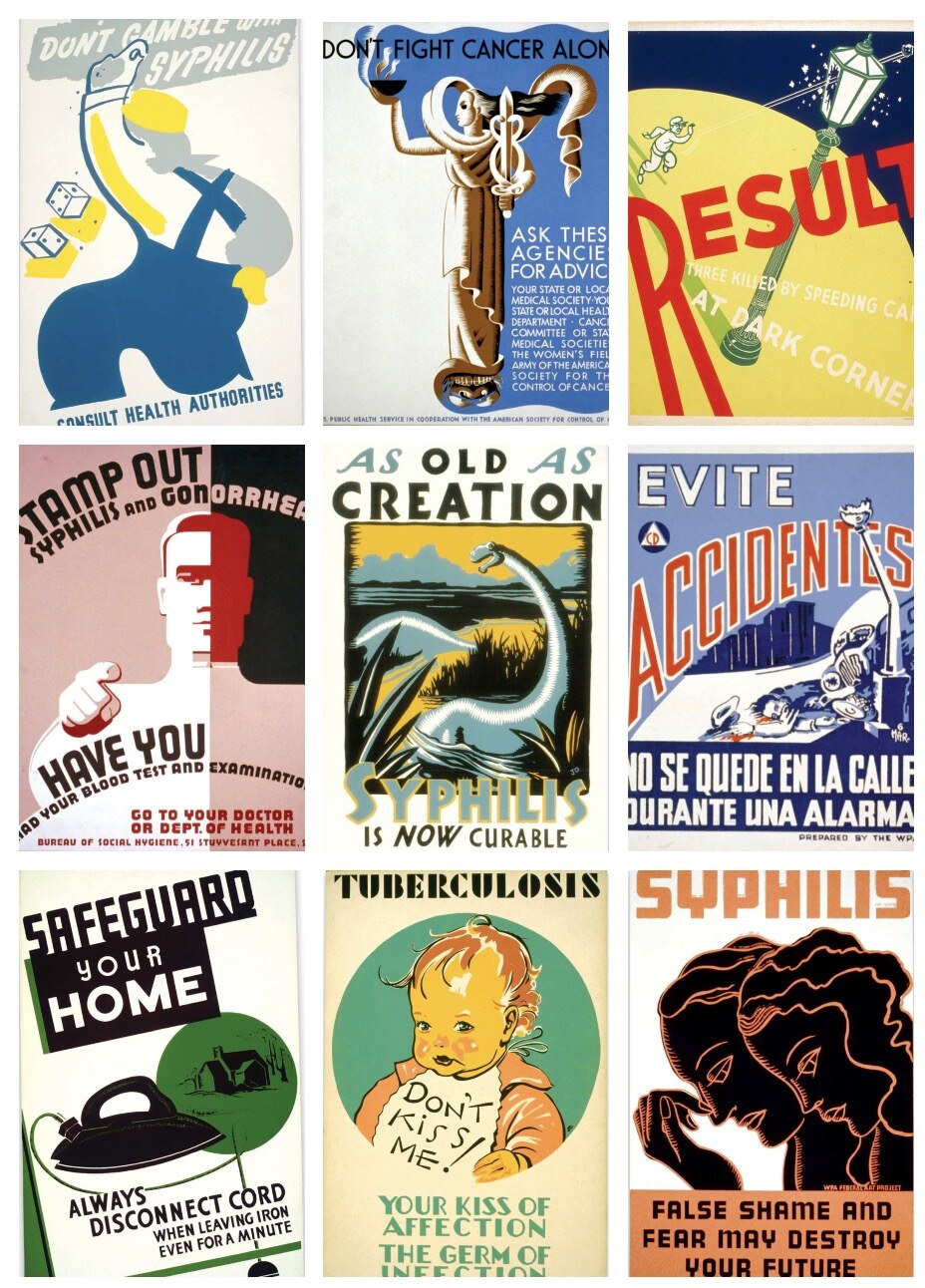

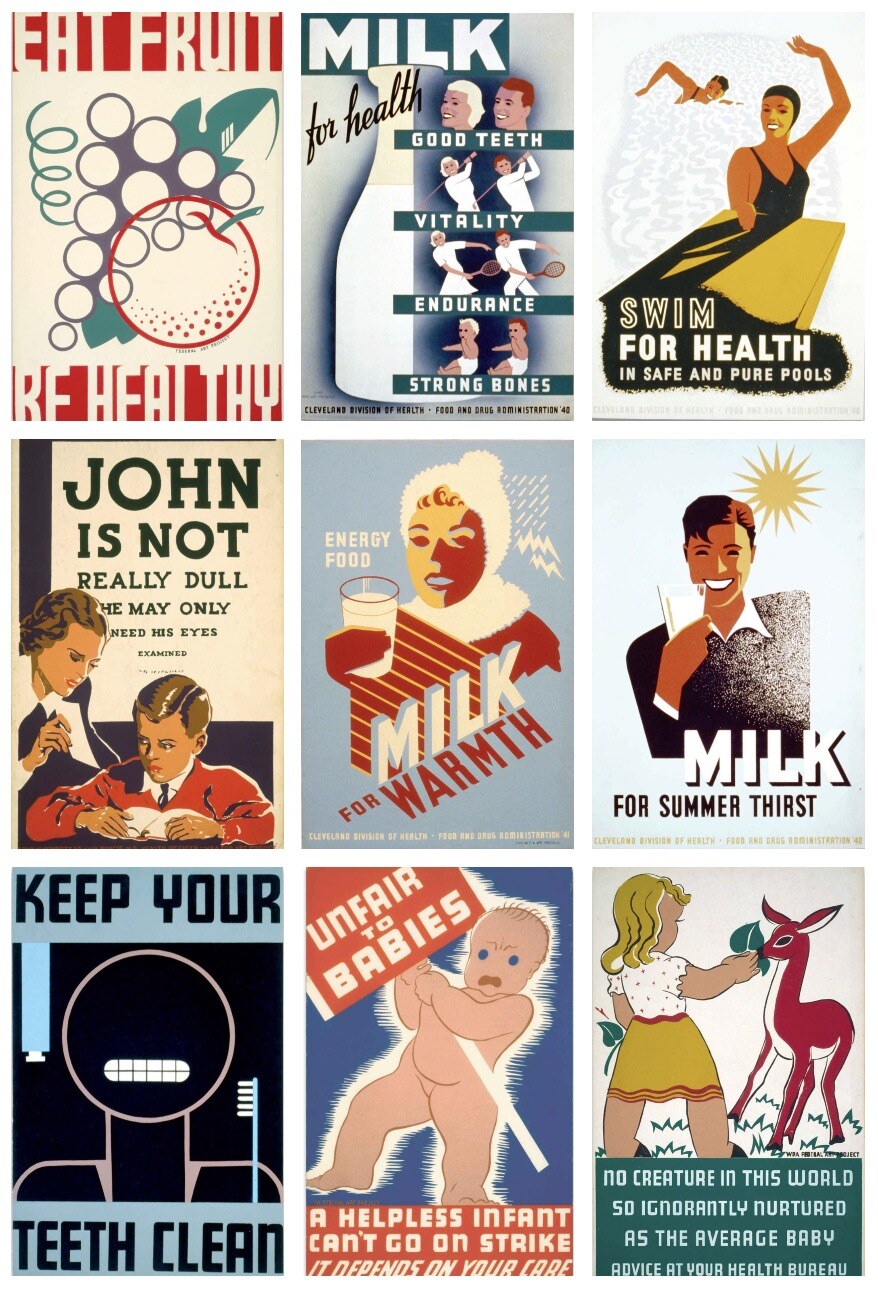

I worry that contemporary liberals have lost the language necessary to even talk in terms of great public services. We are almost at the point where, if public libraries did not exist, it would sound like a crazy socialistic idea to propose one. British Labour leader Keir Starmer, who has maddeningly been spending recent weeks discouraging people from supporting a major UK labor action, said recently that the focus of the next Labour campaign will be “wealth creation” and “making Britain richer,” and “we won’t retreat to our comfort zone on public services.” But exactly what both Britain and the U.S. need right now is for someone to make a strong case for public services, and to destroy the “neoliberal” idea that government exists merely to provide the “infrastructure” for the free market to function atop of. We have seen over the course of the coronavirus pandemic that the U.S. government almost seems incapable of treating a pandemic as a “public health” problem requiring collective solutions—note the strange lack of public service announcements and effective public information programs. Contrast this with the 1930s, when the country’s most creative and cutting-edge artists were enlisted to produce public service announcements. A sample of great WPA public safety posters, from the compilation Posters for the People:

When was the last time you saw something produced by a U.S. government agency you could describe as fun, creative, and strange? (Or, frankly, “useful”?)

We need to recover the WPA vision of the public good, where everyone is entitled to the best and the government does not leave the production of culture and leisure to the private sector. Pools, gymnasiums, carousels, good art, writing classes—all of them make us better off and should be provided free, under a conception of “public works” that is broader than the contemporary concept of “infrastructure.” It’s absurd that so many of our great public paradises were built in the 1930s and 1940s. We can build more of them today, but to do it, we have to reignite the spirit behind the original WPA.