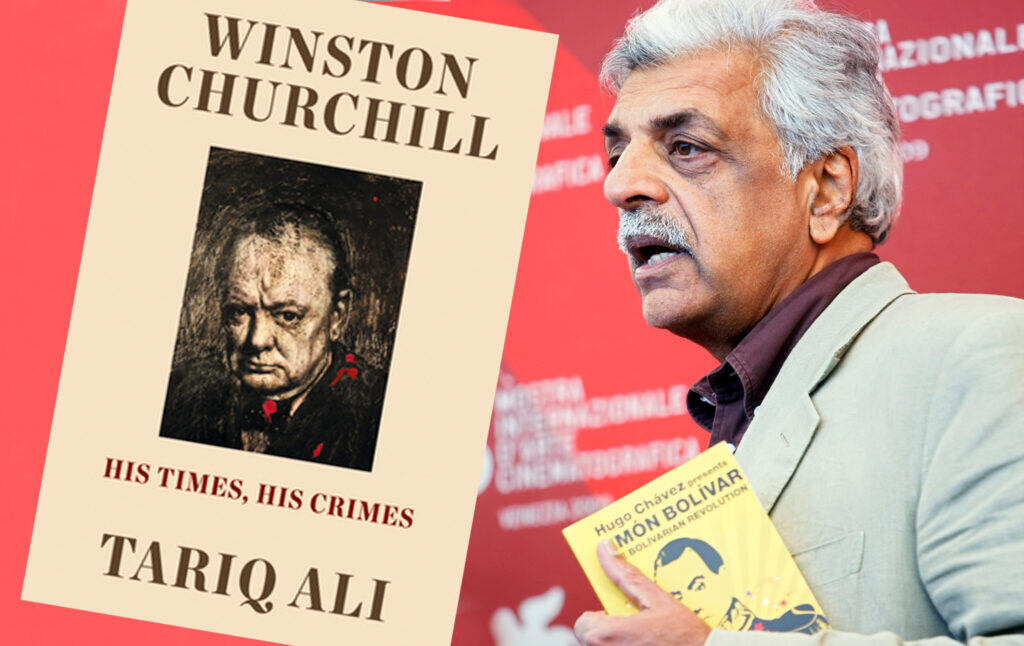

Tariq Ali Busts the Myth of Winston Churchill

The leftist writer discusses his new book about Churchill, which aims to situate the mythologized leader in the context of empire, and to detail Churchill’s forgotten Imperial crimes.

Tariq Ali is a legendary writer, activist, and public intellectual. He is the author of several dozen books, including The Obama Syndrome, The Extreme Centre, and The Forty-Year War in Afghanistan: A Chronicle Foretold. He came on the Current Affairs podcast to talk to editor-in-chief Nathan J. Robinson about his forthcoming book, Winston Churchill: His Times, His Crimes, available from Verso Books. This interview has been edited and and condensed for grammar and clarity.

Robinson

Churchill, of course, has been dead for half a century. There are thousands of books on Churchill. So the decision to write a book about Winston Churchill, in 2022, a passionate and angry book, is one that must have come from a particular motivation. I want to start with the myth that you are trying to bust in this book: the Churchill legend. Before we smash the statue of Churchill that exists in the popular imagination, perhaps we could start with your explanation of the received image of Churchill that has been passed down—one that you think is so dangerous and so necessary to counter as to require a book like Winston Churchill: His Times, His Crimes in the 21st century.

Ali

The person who really pushed for me to write this book some years ago was Mike Davis, who I think is well known to readers in the United States for his own amazing work. And he said it was needed because there was a great deal of confusion; no one knew that much about Churchill. But the myth continued to grow.

So I sat down and looked at the number of books that exist on Churchill in the English-speaking world. The last time I looked, they were reaching 2,000. And it’s not that some of these books are not good. They are, but very few. By and large, it’s hagiography. And it’s building up his image yet further. The reason for that, I think, is twofold, which I can only explain in the following way: when Churchill was alive, including during the war, and after the war, he was often criticized, reviled, and painted out to be a blundering reactionary politician, which he was. So it’s the tiny period of the Second World War—when at a critical moment, he became Prime Minister, and was the Prime Minister of Britain during the bulk of that war—that his reputation was built up.

But interestingly, even then, despite that buildup, he wasn’t popular. He was neither popular inside the Conservative Party, his own party, nor inside the army. He was not popular with the people at large. Otherwise, you can’t explain how immediately after the victory in the Second World War—won largely by the Soviet Union and the Red Army and the American war industry—Churchill lost the election to the Labour Party, which ran on a sort of leftish social democratic program, and defeated the Great War hero.

So the second phase, the real phase of the Churchill as a household God came when Mrs. Thatcher was in power. She decided to launch a 10-day war against Argentina, which had occupied the Falkland Islands. (It wasn’t British territory in the first place. But anyway, that’s a different matter.) And she started using Churchill. This use of Churchill was tied in to attacking Churchill’s opponent, or Britain’s opponent, which was Hitler. And so we who were fighting him were Churchillean and those who were opposed to the war were appeasers. This was used through all the wars that were fought by Britain from 1982 onwards, and most recently, Nathan, you’ve probably seen this, the Ukrainian President Zelensky.

Robinson

Even more so than Margaret Thatcher, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson explicitly models himself on Winston Churchill. He wrote an entire book about Winston Churchill which seems to be an implicit argument that he is almost the reincarnation of Winston Churchill because he writes about Winston Churchill. His descriptions of Churchill seem to be descriptions of himself, and he seems to have launched this second phase of the revival of the Churchill myth.

Ali

Well, Thatcher used him. Tony Blair used him. And now it’s Boris Johnson’s turn. Boris Johnson is a better writer than both Thatcher and Blair and has produced quite a readable book, which went on to the bestseller lists before the Brexit referendum. And in this, as you say, he is trying to identify himself with Churchill. There are phrases quoted in the book denouncing Churchill, mainly by conservative members of Parliament. Boris publishes these with great delight, because a lot of the same things are being said about him today. And as he points out, they were said before and during the war by Tory MPs, etc. And it doesn’t quite work or serve his purposes. But there’s no doubt he’s a huge admirer of Churchill and did do a considerable amount of reading before he wrote that book.

Robinson

I think there would be a liberal temptation to deny Boris Johnson his right to compare himself to Churchill and say, How dare you? You’re no Winston Churchill. But we on the left are more inclined to grant him his comparison. And to say that if you wish to compare yourself to the portly imperialist buffoon Winston Churchill, go ahead. It may be illuminating to compare Churchill and Johnson, because there is a continuity in the style of politics, in the underlying nostalgia for empire. Johnson explicitly wishes to restore the very project that Churchill devoted himself to.

Ali

But he knows he can’t do that. And he knows that, effectively, the British are locked into U.S. defense and foreign policies. And Churchill is a sort of substitute for not being an empire today. We don’t have an empire; we’re effectively a U.S. appendage. [Note: in his book, Ali refers to the U.K. and Australia as “testicle states” of the U.S., a line that appeared to annoy the reviewer in the conservative Spectator.] But hey, we’ve got Churchill which they haven’t—not realizing that the bulk of Americans don’t care whether they’ve got Churchill or not. Not many of them are that interested in Churchill or even U.S. foreign policy, except in times of war.

So that’s the function of Churchill: this is our heritage, what a great leader he was, and then using him as an empty fascist symbol, which is only very partially true. I mean, what I demonstrate in the book is that Churchill, as Prime Minister during the war, did a number of appalling things. The crimes are listed. For one, before the war, and during the war, he was a supporter of the Spanish fascist dictator Francisco Franco. He supported Franco like Hitler and Mussolini did in the Spanish Civil War. He supported Franco throughout the Second World War; he would not tolerate any attempts—because the U.S. was slightly nervous of having Franco listed on their side. But Churchill devised a formula whereby Spain wasn’t in NATO then, but was let in soon after Franco died. So in Spain, his positions were appalling.

Of Mussolini’s Italy, he was a terribly open admirer. He said, what a great role Mussolini was playing in Italy. [“I could not help being charmed by his gentle, simple bearing,” Churchill said of Mussolini.] And then during the war, the Bengal Famine, in which Churchill refused, explicitly, to intervene to stop that famine. There’s still a big debate on it. The British government certainly was largely responsible because the British Viceroy in India, Lord Wavell, was pleading with them to divert some food this way. They had hundreds of thousands of people die. The British War Cabinet, Churchill backed by Attlee, refused to do that. And the final death toll is debated. Up to 3 million people died. T

hen what he did in Greece was the order given to the British commander, who the resistance had allowed to enter Athens, that if the resistance doesn’t do as we say, treat Athens as a colonial city. And the bloodbath that occurred in Greece as General Scobie tried to crush the Greek resistance.

I mean, I just had to reread those accounts, Nathan, for the book. They are horrific. And I have to say, totally backed by the Labour Party in Parliament, with the exception of a few courageous MPs like Aneurin Bevan and a handful of others, but by and large supported by Labour. So I just wanted to create and provide an image of Churchill that was more in touch with the reality of his times and what followed afterwards once Thatcher had started using him. I may be wrong, but I have this feeling that this book will be better received in the United States than in Britain.

Robinson

I think that’s a fair supposition. We actually have a review of the book running in Current Affairs today, and what the reviewer says is that almost all of this old discussion of Churchill focuses on the narrow period of the Second World War. But of course, he had a very long career. And what you do in this book that a lot of people don’t do is view the Second World War period as just one period and look at the rest of Churchill’s career.

You also look at Churchill from the perspective of countries other than Britain. If you are non-British, if you are in one of the countries that was subjugated by the British Empire, Churchill immediately looks very different. You document all of Churchill’s various imperial atrocities. And not just Churchill. You really are talking about how his times are just as important as his crimes in this book.

Ali

I agree. Yes.

Robinson

You talk about Churchill as a representative of his class and as a representative of the power system. You try to understand what Churchill looks like from the perspective of those who were victimized by empire.

Ali

Absolutely. That was the aim of the book. Your listeners might find this mildly entertaining: I was giving a talk several years ago at Macalester College, in Minneapolis, and I was debating Niall Ferguson, a British conservative historian, who was at Harvard then. And there was an American, whose name I honestly have forgotten because there’s nothing to remember. But he was a sort of open supporter of Mussolini. So there are two of these guys and myself. So the debate, as you can imagine, was quite energetic. But when I came and denounced British atrocities in Kenya—which I said are virtually ignored by British historians, meaning Ferguson—he protested. He said, “None of this is true. None of this happened.” It became a shouting match.

But later—after Caroline Elkins, also at Harvard, produced these amazing studies of Kenya, Britain’s Gulag, and she’s now just produced a book on the British Empire—the line of the English historians has changed as well. They now admit that Kenya, which they ignored in their own writings on Churchill, was actually a fairly appalling episode and part of Imperial history. So this is the way in which history is written. I’m pretty convinced that if Caroline Elkins and one or two others had not highlighted the Kenya atrocities, quite a few of these conservative or liberal historians would have let it pass.

So that’s why the book is quite broad in scope, going sometimes a long way back into history, to show what the British working-class movement was, to show the radical currents within it, and to show how, by the early years of the 20th century, it had been captured by labourism and had become quite tame and conformist. Hence Churchill’s and the conservative government’s ability to crush the general strike. No real opposition was planned. And the minute they got a chance, the trade union leaders capitulated.

But Churchill in that struggle, too, told a lot of lies because he edited the government paper, the British Gazette, which was the voice of the government during the nine days of the general strike. So the book isn’t personally about Churchill. It places him in context and says, This is what he really was. Take it or leave it. And, you know, I use Brecht’s famous quote, in Galileo Galilei: “Pity the land that needs the hero.” Britain needs this hero for completely bad reasons. It’s the only way they imagine they can catch up, or at least be seen or deceive their own people that, hey, we are on the same level as the United States. This is a special relationship, a view held largely in Britain and not in the United States.

Robinson

In terms of Churchill’s career outside of the Second World War, where even there you point out that Churchill was less a principled opponent of fascism, and more simply recognized that Hitler’s intentions were expansionist when other people didn’t. Is it fair to say that the general trajectory or the general theme of Churchill’s career was the suppression of labor movements at home, and the maintenance of a brutal Empire abroad? His commitments were the upholding of the British class system and the maintenance of the British Empire?

Ali

Exactly right. And not just that, but maintaining the British class system in a fairly counterproductive way, just even looking at it for a minute from the point of view of the British Imperial ruling class. Their failure to reform their own class system meant that the officer cast of the army was recruited from a very small group of upper-class families, aristocratic families who had a tradition. When they rebuilt the army after the defeat of the English Revolution and Cromwell’s death and the restoration of the monarchy, they were very careful how they built it. And one mechanism they used was class and also having people from the royal family in charge, technically, speaking, of all the regiments, including the Queen, including her kids, including, you know, anyone they can lay their hands on, who’s part of the royal family. There were some very clever generals, no doubt, but by and large, because the catchment area for recruiting officers was very limited, it affected the British Army in the Second World War. In Parliament, Aneurin Bevan made this remark even before Singapore fell in 1942. Churchill had said Singapore would never fall. It was very well stocked, etc. And Singapore fell. But before it fell, Bevan said in the British Parliament that what people don’t realize, and what the government certainly should realize, is the very restrictive nature of the officer corps in the army. He said, if Field Marshal Rommel had been an Englishman, or a British citizen, he would never have really risen above the rank of sergeant because he didn’t come from that background. And that even the Germans were better at recognizing talent than the British were. The British relied too heavily on class.

Robinson

I think there is a defensive reaction to accusations against Churchill— especially to people now pointing out his racism—that treats his racism as a minor character flaw separate from policy. And one of the things that you point out in this book is that Churchill’s racism was not just a small part of his political identity; it was the foundation of his worldview, essentially. He was an explicit white supremacist who believed that it was the right of the British people to rule over, with extraordinary brutality, the non-white peoples of the world and to resist, with extreme violence, those peoples’ efforts at self-determination. And until we understand what this means, what this caused—the immense human suffering—we can’t really understand Churchill at all. We’re not really even seeing what Churchill was and what Churchill did.

Ali

This is absolutely true, Nathan. The thing is, all his epigones and defenders can say, Oh, well, those were different times. Well, hang on a minute. As late as 1955, in the middle of the last century, there was a discussion at cabinet level, as the Tories were preparing to win yet another election, as to what the main campaigning slogan should be. And Churchill was asked. They turned to him, and he said: “Keep Britain white.”

He wasn’t joking, either. The influx of migrants after the Second World War from the West Indian islands, and from India and Pakistan, was badly needed in order to get the British economy going. They’d lost a lot of manpower during the war, and one of the recruiting ministers who went to recruit nurses in the West Indies was actually Enoch Powell, another irony. And on occasion—I think I’ve got it in the book—Enoch Powell attacked Churchill for being too racist.

It’s not something you can laugh off. He basically referred to Native Americans and the Aboriginal Peoples of Australia as lower-grade races. And the Anglo-Saxons were the superior white race. As you said, he was a white supremacist. He said things which few other politicians could say or wanted to say publicly. He shocked Henry Wallace, FDR’s Vice President, during a trip to Washington when he said that after the war, the superior English-speaking races have to rule the world. And Wallace was shocked. He actually wrote in his diary that it just took him aback, the blatant racism. And Churchill said, Well, I—whatever you call me, doesn’t matter. But it is true. We just are a superior race.

How can anyone in this day and age justify that? So you see that when atrocities are committed by other imperial powers, not Britain, Churchill, very rarely … I couldn’t find a single comment by Churchill on the massacre of the Congolese by King Leopold, where, according to Adam Hochschild, one of the leading historians of that period, the Congolese were killed in the most brutal fashion. No mention by Churchill. There were three other people who did mention it and wrote fantastically savage accounts of it. One was Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of Sherlock Holmes, who went in and read an account of these atrocities and wrote this phenomenally influential book which sold hundreds of thousands of copies in a few weeks. And then there was Joseph Conrad, who wrote a novel. And then there was E.D. Morel, and others. But not Churchill, not anyone from the Conservative Party.

You can add to that the massacre in Nanjing in China by the Japanese, a horrific massacre of the Chinese people, ordinary Chinese people—these weren’t soldiers. The soldiers of Chiang Kai-shek and the government town had fled and the Japanese wanted to assert their military and semi-racial superiority because they’d always had this dislike of the fact that people always talked about Chinese civilization and Japan being part of it, etc. So there were a mixture of reasons, but the brutality in Nanjing was so bad that the German consul wrote a letter to Hitler saying this is just completely out of control, what I witnessed. The other Germans in Nanjing helped some survivors with medical aid refuge within Nanjing. Did the British? No. A single mention of the Nanjing Massacre in the Churchill potboiler histories? I haven’t found it. So it was not just what you did yourself. But because of what you were doing, it was difficult for you to attack other European empires indulging in even worse atrocities than you did because it was, in part, a trade union of imperialist leaders. We don’t attack each other. Solidarity against the common enemy.

Robinson

Something that you emphasize that’s not really widely understood or accepted or discussed is that the white supremacism of Winston Churchill, his indifference to the suffering of people different from himself, led to millions of deaths. You have a long, long section on the Bengal Famine. Churchill’s defenders say, Well, you know, they didn’t have much information. And what you point out is that this comes from a complete indifference. Churchill explicitly did not believe that it mattered if those millions of people died, because to him, their lives were essentially worthless.That’s the root of it, right?

Ali

Their lives were expendable precisely because they were Indians. Churchill did know his history of British India. And they were Indians from a part of India which the British really began to hate, which was Bengal. And one reason for the hatred was that this is where the opposition currents to the British Empire first grew. This is where a small layer of intellectuals emerged who learned to speak English and read all the books considered not good for them. And this is also the province where, during the war, the very radical nationalist Congress leader Subhas Chandra Bose called for a second war. He said Indians shouldn’t be supporting the British war effort in any way, and he set up the Indian National Army with the aid of Germany and mainly Japan, asking them to release Indian prisoners of war so he could mold them into an army, which he did. And there were actual clashes between the Indian National Army and the British army on the border with Burma.

And when these traitors, as the British call them, were tried, their popularity in India was at such a height that Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India, donned his lawyer’s robes and went into court to defend them because though that had not been the position of mainstream Congress, Nehru knew how popular this view was. So Churchill hated them.

He never liked India, basically. There was another layer of British civil servants, mainly, who were quite hostile and explained their hostility to Bengal. But some of them then used to idealize the Pashtun tribes in the north where they were descendants of Alexander the Great, which has never been proven, by the way—there’s an element of proof: six feet tall, light skin, blue eyes, light hair, warriors. … So there was a whole mythology set up, in which warriors were good, even though they sometimes fought against us—the British said Kipling had been an example of that—but anything is better than the Bengalis. So this went very deep into British colonial society. Some of the same arguments against the Bengalis were used when Pakistan was broken up in 1971. Many of the Pakistani military officers were using similar language against the Bengalis, as had been used by the British. So it went deep. And the same applies to the Kenyans, the black Rhodesians, the black South Africans, doesn’t matter. As long as the white race was in charge—that was very much Churchill’s opinion—things could only get better.

Robinson

He also had a role in suppressing Irish nationalism.

Ali

That was a problem. When they fought against the Irish, they couldn’t introduce race, but they introduced religion. The Protestant Reformation had created more modern societies than the backward Catholic Church, which was partially true of the Catholic Church in Ireland. Another argument could be made for some of the activities of Catholic militants, particularly in Italy. But we won’t get caught up in that now. But the problem of race was overcome by saying that these Irish Catholics are just incredibly backward, defending the famines, which forced large numbers of Irish people to migrate to the United States, defending the atrocities for which Churchill was directly responsible, the creation of what were effectively death squads, known as the Black and Tans which created havoc inside Ireland. Then Churchill himself, with others, played a big part in dividing the Irish nationalists and backing one side, which he felt would be more friendly as far as Britain was concerned, which led to a ghastly, awful unnecessary civil war in Ireland itself.

And the other big fight was against the Boers in South Africa who were abused, killed, or locked up in concentration camps. And after Britain had defeated them, Churchill then was obliged to say that, as part of the white race, the Boers were, one has to admit, very courageous, and brave people, which he never could say about, for instance, the Indians as a whole, and the Kikuyu tribes in Kenya who fought against them. This whole business of race was necessary for them to run the world. It was not necessary to run Ireland because Ireland was part of the same area islands in the north of Europe and controlling them was essential though, you know, those who just blame Catholicism also should realize, as I stress in the book, that many of the most respected Irish leaders who fought against the British were actually Protestants. One shouldn’t forget that.

So making it into a religious war was largely the fault of the British. Then the Irish Catholic Church played along with it because they collaborated. Many of the senior bishops collaborated when Irish nationalism … was being brought down. And it’s an unpleasant story. But when they couldn’t use race, they used British superiority, British Imperial strength, etc. And the hatred the Irish felt for them went so deep that they refused to back Britain in the Second World War; they remained neutral. … They just said, you know, the Nazis are obviously awful, but we are not going to back you up.

Robinson

Churchill has that famous quote, “History will be kind to me, because I intend to write it myself.” As you point out in this book, that is exactly what has happened. Churchill, after the war, sat down and wrote a history of the war. Churchill created in part his own myth. When you go back to the actual records, and you look at the discussion of Churchill at the time, it really is quite astounding how different the discussion and the perception of Churchill was in 1945, compared to how it is today. In the 1945 campaign, at the end of the war, Churchill came out and immediately started comparing the Labour Party with the Nazis and saying that they would launch a new Gestapo in Britain. People were horrified. Even the Economist said, you know, Churchill is this crazy reactionary. The public perception in Britain was, alright, well, he was a fine wartime leader, but clearly has no understanding of what Britain needs in the post-war moment. And that’s the consensus of 1945, when you’d expect opinion of him to be at its most favorable.

Ali

Exactly. And this is the problem for those historians who are by and large uncritical of Churchill. They twist and turn all over the place to try to explain it. But Churchill was deeply unpopular during the war. There’s this episode, a sort of footnote in English military history, when in early 1944 soldiers and young officers demanded the right to discuss politics inside the British Army. And they were given permission, but it was limited. And they had elections within army units, largely in Egypt, but not exclusively. And they elected a pseudo parliament. The model had come from the Putney Debates during the 17th century, when radical English revolutionaries had confronted Cromwell with questions about the social structure of England at that time. Why should the richest have some influence in society but not the poorest? These arguments go back centuries. So in the Cairo Forces Assembly, there were finally elections; the Labour Party won a huge majority. Second was the Commonweal Party, a party essentially led by independent-minded liberal and left-liberal intellectuals. The Conservative Party came last.

And this was a harbinger of what happened in the actual elections in 1945. And the Conservatives couldn’t believe that, despite Churchill, they had lost the general election. It took them some time to get over it and had Labour been a tiny bit more radical—even in the second election in 1951, where Labour had the numerical majority, but because of the weird voting system, the Tories actually won the election by a small majority—it would have been different. But that is not something that is talked about too much these days, though it was at the time.

I mean, if you look at an editorial which I quote in the book written by the Times, the Imperial paper of record—it’s an incredibly sharp editorial on what democracy has been and what it doesn’t offer. And the editorial precisely concentrated on things like the right to work, the right to a house, more radical than the final Labour program, by the way, with the exception of the National Health Service. But the mood was shifting even as the war was being fought. Churchill never realized that. He was not a visionary, in that sense of the word, except in a very instrumentalist way. Even before the Second World War was fully won, he was thinking about the Cold War, and what he could do during that war.

Robinson

The last chapter of your book is called “What’s Past is Prologue.” And for the most part, it’s not about Churchill at all. In fact, I think people reading this book will be surprised. It is not, strictly speaking, a biography of Winston Churchill. You are using Winston Churchill to understand history and to understand the present. And one of the lessons that I took from this book, and from this last chapter, is that one of the reasons we ought to study Churchill is to study the way that myths are created, how they obscure the way that power actually operates. And the way that convenient and useful lies get woven into history over time. These lies and mythologies then come to justify the maintenance of the same kinds of barbaric systems that have existed generation after generation. Busting the Winston Churchill myth is important not just because he’s an important historical figure who people are not telling the truth about, but because the same myths are used today, in a certain way. Talk about the important lessons of your discussion of Churchill and the reason why you found it so important, for our moment right now, to talk about Churchill.

Ali

Well, it’s true. I didn’t pretend otherwise. It’s made very clear in the preface—this is not a traditional biography of Churchill. So I should have said: If that’s what you want, don’t read this book. This is a book designed to recover an alternative history—which existed and which is now forgotten—about Churchill’s role as an imperialist warmonger, as someone who loved wars, whether there was an actual war in which he could participate, whether it was a class war against the workers. There’s hatred for him in Wales—for instance, where he was involved in crushing mining strikes at Tonypandy, and where they rewrote the history but some of the documents have been discovered—that went on until his death. There was not a single Welsh Local Government Council that agreed to donate funds for his statue. And it’s worth remembering that. That’s why people like actors who played him, like Richard Burton, utterly loathed him. So it’s something worth remembering.

And so I felt it was important that this history was made clear. Otherwise, for the younger generations, all they have of Churchill are movies, made largely now by Hollywood, television soap operas which are basically uncritical. [I wanted to] tell history as I see it, but as large numbers of other people used to see it, and to recover, in other words, the real Churchill, the real Empire—what it was, what it did. And of course, Churchill was not responsible for these crimes alone. It was a system. And that system in the old days used to be called imperialism. And now it’s referred to slightly more coyly as empire. … And the only reason Churchill is used for that is because he was one of the most ardent defenders of the whole concept of Western empires.

And if you look at the world today, what’s happened in the 21st century, Churchill was used in the sense that everyone opposed by the British and also by the United States was described as Hitler. Why? Same reason. So, Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt was a Hitler because he was threatening to take back the Suez Canal. Mohammad Mosaddegh was a semi-Hitler because he had nationalized Iranian oil; Saddam Hussein, a long standing Western ally, became Hitler because he wouldn’t cave in; Milosevic in Yugoslavia became Hitler because he wouldn’t agree to Western plans for the region. And so the first war of NATO enlargement was the bombing of Yugoslavia, and Milosevic was Hitler.

So all this stuff of inventing past criminal figures, basically beautified and prettified Churchill. So I just thought it was time to do a book which went beyond simplicity. Churchill himself was very proud of the fact that an English-speaking, predominantly white, empire had been handed over to the British Empire. Saudi Arabia was handed over to Roosevelt actually, during the war. There are lots of accounts of that. But it wasn’t just the British who did it. It was the French who handed over Indochina to the United States. It was the Dutch who allowed the United States to become the dominant power in Indonesia after one of the most horrendous massacres of the 20th century, when the local generals were armed by the United States and funded and ideologically prepared by the CIA, and ended up killing over a million communists, socialists, and trade unionists, in 1965.

So the empire and the imperial system continues. And that is also part and parcel of the ideology that was deemed necessary to promote Churchill and his cause after 1982. So the Churchill cult is not a revival, because it didn’t exist like that when he was alive or even fought the war. It’s not a revival. It’s a completely new creation, and it carries on today, but I think it will die. I think history now owes us a period, having indulged in crazed idolatry in regard to Churchill and empire. But given what’s still going on in the world, I think it is time now for history to allow a little bit of iconoclasm. It’s time to be iconoclasts again. This book, I hope, will help in that.

Robinson

As you point out, there has recently been a wave of historians, from Mike Davis to Caroline Elkins to others, excavating some of this hidden history and making sure that people aren’t allowed to forget it. This book is a new contribution to this effort to tell the truth about what happened and to show the lives of those who are overlooked consistently in mainstream accounts. Thank you so much for talking to me today.

Ali

Thanks. A great pleasure.