How ‘You’re Worth It’ and other Femvertising Takes the Radicalism out of Feminism

Exploring how the rhetoric of merit shows up in consumer advertising toward women, conflating consumer purchases with women’s empowerment.

“The dream I’ve always believed in is, no matter who you are, no matter where you come from, if you work hard, pull yourself up and succeed, then, by golly, you deserve life’s prize.”

— Ronald Reagan, 1983

“Make your hair beautiful—with Preference by L’Oréal. Shining color and nothing conditions better. So buck up. Develop an attitude. I sure did. Just say, I’m worth it.”

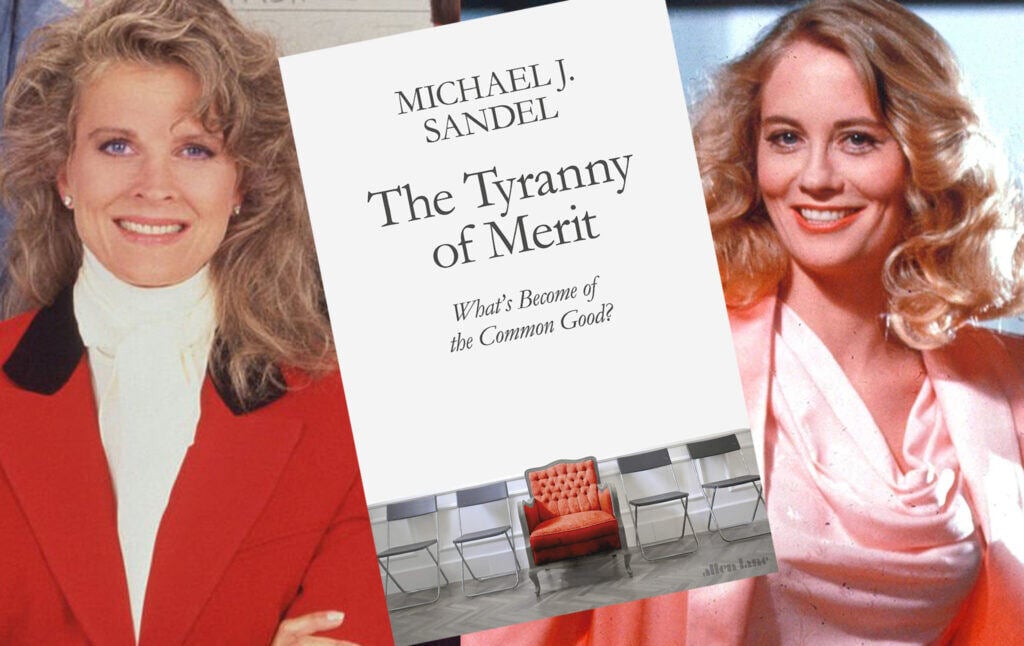

— Cybill Shepherd, 1993

In the 1980s, a new archetype strutted across the screen: the fictional female executive—plucky, scrappy, and with a certain entitlement. She was often blonde, almost always white. She could be seen in films like Working Girl and Baby Boom, or television series like Murphy Brown and Moonlighting, the dramedy which revived Cybill Shepherd’s waning career in 1985. Here was a woman whose workplace was a veritable catwalk, whose Fendi briefcase swung with the bounce in her step. Here was a woman who, while no doubt paid less than her male equivalent, boasted a closet of designer pantsuits inspiring wide-eyed legions to chase the trail she blazed. Here was a woman vying to have it all—because she deserved it all. Here was a woman who knew her “worth.”

But how is “worth” measured, other than by the metric of financial compensation—or the lack thereof? Often, it’s measured through consumer signifiers of female success. For many women, conspicuous swag—from handbags to lip gloss to Lululemon mats—may itself be imagined as material substitution for financial solvency. With such snazzy accoutrements, upwardly mobile women may ask themselves: what can it matter that we have saved only a third of that of men for retirement, hold “about two thirds of U.S. student loan debt,” and will have lost $600,000 apiece in predicted lifetime income during the pandemic? Isn’t dressing the part key to ascending the shaky economic ladder—even more so if so few women are there to hold it steady?

Critics of “girl boss” metrics for female success are, thankfully, not in short supply: leftists like Yasmin Nair, Jessa Crispin, and Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor have cogently exposed the fallacies within glass-ceiling and representational approaches to gender (and racial) equality. Being a female Fortune 500 executive doesn’t make one a feminist any more than bleaching one’s bob constitutes a brazen expression of womanly worth. Mistaking one’s individual achievements (or vanity!) as boosting all of womankind is incredibly tempting—who doesn’t want to think rather loftily that her gains are not just hers? But this kind of thinking distracts from a necessary consciousness that might lead to fundamental change—change that is based on building a more just society for all, not just those economically and racially similar to ourselves, change that prioritizes women’s contributions to a more just society over their acts of consumption.

Certainly, it’s seductive to think that making enough money to buy nice things imparts value to us as women. To this end, marketers of consumer goods have shamelessly deployed the rhetoric of worth and deservingness to appeal at once to our desire to reward the individual self (a self uniquely special) and to the idea that we can lift up other women with our purchase. A conceptual slippage occurs: the idea of “worth” traditionally applied to the product (is it worth buying, as in “Does it give value for money?”) is instead applied to the consumer (you are valuable enough to deserve the product). Women are conditioned not to evaluate the value of the item but the value of themselves—and are reassured by the advertisement that they are indeed meritorious enough to justify the purchase. Similar slogans such as “you deserve it” become “you deserve it,” as in, “you in particular deserve it, and others do not, and that makes you special.” Comparisons of personal merit are encouraged. Was Cybill Shepherd “worth it” because all women are worth it? Or because she was rich, white, and exceptionally beautiful, patently unlike most of her audience? What marketers hope comes off as feminist mantra mutates into self-congratulation and the implicit denigration of others.

It turns out, perhaps surprisingly, that the pernicious notion of worth in American advertising directed toward women has connections to what political philosopher Michael J. Sandel has called “the tyranny of merit.” In his latest book, The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good?, Sandel traces the inherent connection between the ideology of “meritocracy” and rising inequality by focusing primarily on economic disparities exacerbated by the ever-increasing demand for a four-year college degree. As a professor acclaimed for his Harvard “Justice” course, Sandel is possibly the very last person anyone would associate with glamour, fashion, or blown-out girl bosses. But The Tyranny of Merit shows how meritocratic thinking and policy-making have fostered a culture in the United States that privileges individual talent and accomplishment above the betterment of society, leading to self-righteous hubris:

“The heart of the meritocratic work ethic … celebrates freedom—the ability to control my destiny by dint of hard work—and deservingness. If I am responsible for having accrued a handsome share of worldly goods—income and wealth, power and prestige—I must deserve them. Success is a sign of virtue. My affluence is my due.“

Feel familiar? Until relatively recently, my own attitude toward upward mobility aligned with this mindset, and I didn’t realize that, historically speaking, this thinking is fairly new. Born in 1979 to lower middle-class parents (at the time, my father was a letter carrier and my mother a college student), I’d assumed that what Sandel calls the “rhetoric of rising” had been a crucial part of the American ethos long before I existed. But, as Sandel takes pains to emphasize, “the language of merit and deservingness” has only dominated political discourse since the 1980s, grounding my childhood sense that hard work and intelligence could help me go “as far as my talents would take me.” As a young girl with a penchant for Star Search and a chemistry set in the basement, I believed that going “far” meant going places that girls like me were not usually permitted—but that I would go if I proved my merit. I would outpace my Midwestern classmates and catapult to greatness. I would win the national spelling bee, master college math in middle school, and become a neonatologist and win a National Book Award for poetry.

That I did not accomplish all (any?) of these things did not damper my faith in meritocracy as an inherently feminist route to success. Nor was I discouraged from judging other women who did not seem to work quite as hard to be good at everything, all of the time, and look good doing it (fun fact: my senior creative writing thesis was titled “Learning to Run in Heels”). This undeniably smug attitude—which surely I have not been alone in holding—betrays the problem Sandel describes within a so-called feminist framework. Credentialism, he writes, is the “last acceptable prejudice,” and as such has eroded the liberal elite’s connection with the less formally educated, leading to greater political polarization, of which Trumpism is but one symptom. Throughout my own lower middle-class coming-of-age, and arguably that of an entire generation in the ’80s and ’90s, “you deserve” became doctrine and slogan for both countless politicians and popular advertisements—from Reagan to McDonald’s, from Clinton to De Beers. “As language of deservingness infused popular culture,” writes Sandel, “it became a soothing, all-purpose promise of success.”

How might this promise specifically appeal to a female demographic? Young women like me did not only deserve to consume nice things because we were hard-working and “talented,” but because we were female, and as such belonged to a group long deprived of our due. In this light, Sandel’s Tyranny of Merit can be placed in dialogue with an array of thinkers who have analyzed female consumption, like Bitch magazine cofounder Andi Zeisler, whose 2016 We Were Feminists Once: From Riot Grrrl to CoverGirl®, the Buying and Selling of a Political Movement tackles the displacement of feminist activism by commercial interests; fashion journalist Dana Thomas, whose 2007 book Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster explores the democratization of luxury fashion; and author and activist Yasmin Nair, whose 2017 “Bourgeois Feminist Bullshit” exposes the emptiness of “choice feminism.”

In We Were Feminists Once, Zeisler chronicles the rise of “market place feminism,” rampant in the “femvertising” for which I and millions of other women so often fall. “It’s decontextualized. It’s depoliticized,” she asserts. “And it’s probably feminism’s most popular iteration ever.” As Zeisler makes clear, from the “new woman of the late nineteenth and twentieth century” who were peddled Shredded Wheat (“Her Declaration of Independence!”) to the Lucky Strike and Virginia Slim smokers of yore, marketing notions of feminist progress long predate the “rhetoric of rising” that, as Sandel argues, swept the nation over the past forty years (and can hardly be pinned just on the right wing). “[Bill] Clinton and Obama employed rhetoric of rising more than twice as often as Reagan,” he points out. No wonder so many were so receptive to Obama’s lure, embracing his faith in meritocracy as a social justice cause—which for so many wide-eyed women canvassers (like me), was also an implicitly feminist one.

Sandel gets the “rhetoric of rising” right in terms of its national impact, but argues, a bit puzzlingly, that Reagan and other politicians of the ’80s and ’90s led the way. “As the rhetoric of rising became prominent [in politics], the language of merit and deservingness found growing expression throughout the public culture,” he claims, citing the McDonald’s “You deserve a break today” campaign as one salient example. But in light of the long history of femvertising (not to mention the fact that this McDonald’s campaign launched in the ’70s), it seems just as conceivable that the political rhetoric of “deserving” was being shaped by marketing tactics that had already proven effective; what can sell a product, in other words, can also sell a politician or governmental policy. If one deserves a burger break, why not a tax break? And with that extra tax money, why not splurge on a hot stone massage (an indulgence that, of course, you also “deserve”)?

Focusing on “the common good,” Sandel is not specifically concerned with the gendered implications of the tyranny of merit. But the “you deserve” catchphrase has, in the last twenty years, become the lingua franca of women’s marketing and self-help sisterhood. Suze Orman’s 2012 bestseller The Money Class: How to Stand in Your Truth and Create the Future You Deserve conflates personal wealth accumulation with feminist liberation. Motivational speaker and spiritual psychologist Dr. Grace Cornish’s 2003 volume You Deserve Healthy Love, Sis!: The Seven Steps to Getting the Relationship You Want promises to help Black women find romantic (heterosexual) fulfillment. In terms of advertising, a Google search for “you deserve” offers a range of examples from across the globe. A 2018 billboard for a Sri Lankan fitness club displays a rusty oil barrel and comments: “THIS IS NO SHAPE FOR A WOMAN … JOIN SRI LANKA’S HOTTEST GYM AND GET INTO THE SHAPE YOU DESERVE.” Meanwhile an ad for (since extinguished) Fire brand condoms wishes a “Happy International Women’s Day” with the tagline “You deserve pleasure and protection.” Another recent ad for ABM Medical Clinic and Cosmetic Laser Services declares “YOU DESERVE THIS” with reference to a deal for six hair-removal sessions (ruefully, only of a small area, and for $600).

The rhetoric of “you deserve” has proven exquisitely suited to selling products and services to women—not least because, over the ’80s and ’90s, women started rising in the ranks of the professional sphere, making enough money to affirm their worth through their own purchases rather than relying on the munificence of men (historically called husbands). What Sandel describes as the two-score ascent of the “rhetoric of rising” in the 21st century is connected to how the fashion and beauty industry has, across the same span of time, marketed itself as accessible—and indeed “feminist”—to the upwardly mobile employed woman. Consumption is the righteous reward for a woman’s talent, nerve, and long hours in the office (or, in today’s gig economy, an overpriced corner of a coworking space like WeWork). The Botoxed business babe and the hairless lady professional are as much the result of the “rhetoric of rising” and marketplace feminism as they are of simple vanity.

In Deluxe, Dana Thomas reveals how consumption of luxury goods, especially by women, became its own form of meritocratic lure in the final decades of the 20th century. On the rise of luxury retail, she writes, “More than anything else today, the handbag tells a story of a woman: her reality, her dreams.” But of course it was not always this way (and is not this way now for millions of women). “[U]ntil the Youthquake of the 1960s,” Thomas explains, consumption of luxury products was limited to only the aristocratic and leisure class, and during the revolutionary 1970s, social barriers that separated “the rich from the rest” fell out of favor. “Luxury went out of fashion,” she writes, “and it stayed out of fashion until a new financially powerful demographic—the unmarried female executive—emerged in the 1980s.” Thomas rhapsodizes about who then gained access to fancy duds: supposedly “anyone and everyone could move up the economic and social ladder and indulge in the trappings of luxury that came with this newfound success.” While clearly this was not true—the vast majority of women were excluded from this “financially powerful demographic”—Thomas makes a valid point: rising disposable income for women over this period was but one factor contributing to luxury’s “democratization.” Postponing marriage freed both sexes to spend more money on themselves. “The average consumer,” Thomas continues, “is also far more educated and well-traveled than a generation ago and has developed a taste for the finer things in life.”

But might this “taste for the finer things” simply be an expression of newfound entitlement for what seems, in Sandelian terms, one’s “just desert” as a citizen? For women over the past four decades, the ability to earn—and spend—as a sign of agency has exploded alongside the “rhetoric of rising” sweeping public discourse. If any given individual deserves certain things, things which were only a few years earlier considered a luxury, would not an individual woman feel it is even more so her reward for hard work, talent, and centuries of oppression? When Karl Lagerfeld redesigned the iconic 2.55 Chanel bag in 1984—specifically appealing to women rising in the executive ranks—would it not be tempting to mistake this chain-strapped, quilted leather treasure for some feminist talisman?

Not unlike how L’Oréal hair dye was once touted as a luxury—“the most expensive hair color in America”—the designer handbag went from distant status symbol to aspirational object. “The It Bag phenomenon is young,” Thomas pointed out fifteen years ago, “and has been wholly created by the marketing wizards at luxury brand companies,” wizards who realized that women could be made to perceive such an accessory as a totem not only of style, but professional status and worth. After all, handbags are decidedly not the domain of traditional romantic gift-giving; rather, like hair dye, they are items that women typically purchase for themselves—and the market has only continued to grow. In 2004, $11.7 billion in luxury handbags were sold; by 2019, they would reach nearly fifty. In the post-pandemic luxury rush, sales have gone up again by 10 percent. By 2028, the global luxury handbag market is expected to reach $94 billion, and it’s hard to imagine these dollars will reflect the unique “stories or dreams” of the consumers. “[T]o democratize luxury, to make luxury ‘accessible,’” writes Thomas, “sounded so noble … almost communist,” but “it was as capitalist as it could be: the goal, plain and simple, was to make as much money as heavenly possible.” Conflating access to luxury goods with communism is, of course, absurd. But the idea that anyone can earn her way to a handbag has held remarkable sway over women. What one carries in her Burberry, in other words, is less important than how it communicates hard work and merit.

In “Bourgeois Feminist Bullshit,” Yasmin Nair counters this specious logic, questioning the value—to women and men—of promoting meritocracy as opposed to actual change in society’s underlying economic conditions. According to liberal feminism, she writes:

“[T]here should be a meritocracy in which anyone can rise from their lowly, pitiful, underpaid position to become the boss. For someone committed to actual material equality, there shouldn’t be bosses, or lowly, underpaid positions, to begin with. It’s not that everyone should be able to get to the top of the hierarchy of female success, it’s that the hierarchy must be destroyed, so that people can do what they want with their lives without having to worry about whether they will be able to feed themselves or their children.“

Does that mean we cannot enjoy a sequined clutch to celebrate a promotion—or simply because we like sequins? Of course not. But to rise in the professional ranks, and make purchases accordingly, does not mean that, as women, we have proven our “worth” to ourselves or others. Nor are these acts liberatory for women as a whole or any person who faces gender-based oppression in an unequal and “meritocratic” economy.

The wellness industry is arguably but the latest iteration of “democratized” luxury—the idea of “deserving” a monthly massage or mani-pedi as a form of “self-care” granted the righteous air of feminist empowerment. What could, after all, be more feminist than a woman choosing to care for her own body and mind—or, even better, “mind-body experience?” But these days, what constitutes self-care is up for debate, from injecting filler into nasolabial folds to consuming smoothies that could grout kitchen tile. When, in the mid-’80s, Audre Lorde, the renowned Black feminist, poet, and civil rights activist, wrote, “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare,” she was battling two forms of cancer. She was literally speaking of her “physical” and “psychical” survival. These days, self-care is hardly the kind of radical affirmation Lorde wrote about, and can refer to almost anything that feels or makes you look good. Any purchase can pass for self-care in the name of self-improvement, especially if it takes a lot of money and time.

Of course, women should have more leisure time, more time not working, and more time to reflect and create. What’s politically fraught is how immediately leisure is conflated with luxurious consumption, and self-care becomes a trip to the spa. It’s as though some women can’t be sure they are genuinely relaxing unless someone else is serving them. Further troubling the (lavender-infused) waters is that those serving tend to be working-class women of color, women who have not managed to climb up the meritocratic ladder to “bigger and better” lives and face challenges such as systemic racism, lack of opportunities due to immigration status, or language barriers. In fields such as skin care specialists and personal appearance workers, women of color occupy over 50 percent of workers. In the field of manicurists and pedicurists, women of color comprise 61 percent of workers, the highest percentage among occupations with large shares of women of color. A 2018 UCLA study of the nail salon industry in the U.S. describes the industry as predominantly female and foreign-born (mostly Vietnamese). Many of these women are self-employed and lack job security; nearly two thirds support children; and a majority earn low wages. We need to be concerned about how all women are able to care for themselves when we purchase self-care.

None of this is to say that women should never get their nails done. Or to say that we shouldn’t feel, on some level, as though these small (or large) luxuries are our “just desert” (tempting to add a second “s” here, as Dove chocolate bars and pricey cupcakes are so often promoted as just that). But to define consumption itself as a feminist act—or one that does anything to challenge sexism or classism within society—and to conflate vanity with virtue, is to paint the “rhetoric of rising” in so many shades of Millennial Pink (Millennials did not create these meritocratic ideals, but have accumulated unprecedented levels of debt to pursue them). In other words, buy that pair of sandals or nail service—but resist the idea that you are contributing to the feminist cause because the boutique is owned by a woman, or because you are a woman and it’s tempting to think that anything done on your own behalf contributes to a greater cause. As Nair astutely puts it:

“Feminism is not something that comes about simply because of the presence of women; it is fundamentally about changing the world so that everyone, regardless of gender, has the same access to material benefits.”

Rather than focus inordinately on what we buy or do not buy, what if we focused on what we contribute to the common good instead—through our professional and family lives along with daily acts of compassion? If the average American woman diverted more of her self-care time to the care of others unlike herself—the poor, the incarcerated, the undocumented (people of any gender)—would that not arguably be more just? And if we devoted more of our “me time” to researching—and voting for—policies that aimed to reduce gross wealth inequity (inequity that almost always inordinately punishes women, especially women of color), wouldn’t that be at least a teeny bit more empowering than buying a second pair of sandals?

If I sound snarky, it is not exclusively—or even primarily—toward the consumer practices of other women. I personally enjoy a full-on head rush from a good shopping trip, and devote no small amount of my disposable income to maintaining what appears to be a whimsical, low-maintenance hairstyle (it is not). I believe that pleasure is a precious part of being alive, and that purchasing things and experiences can be part of that pleasure. I believe that women deserve pleasure—all of us do. And it did feel feminist when I bought a house on my own as an unmarried woman, with savings I had scraped together waiting tables, editing museum publications, and teaching writing and film as an adjunct lecturer. Only five years before I was born, I would not have been permitted to purchase a house without a man’s name on its title! At the time I bought my house, I felt that I had a place in women’s long struggles for equality, but I now believe this is true only to a point. I wasn’t carrying out feminism when I bought my house any more than I am carrying out feminism by buying a lipstick with my own credit card. I was simply benefiting from the struggles of prior feminists to ensure that gender did not preclude the legal acquisition of property. The temporary boost of self-worth from this acquisition, moreover, pales in comparison to the sense of purpose I have gained as a writer and teacher over the past decade—whether promoting the work of a female filmmaker, instructing undergraduates at a state correctional center, or nudging my more privileged students to question the hyper-competitive, meritocratic rat race they have inherited. To be sure, I am not radically challenging systemic inequality through any of these activities, but it is a first step toward contributing, in my own small but distinct way, to what Sandel calls “the common good.”

We are living in a time when, as individual women, we have become algorithmically targeted by marketers in ever savvier ways. As women, we have been tyrannized by meritocratic thinking—meritocratic thinking that has informed, and been informed by, the forces of consumer culture and marketplace feminism. “This way of thinking is empowering,” Sandel argues. “It encourages people to think of themselves as responsible for their fate, not as victims of forces beyond their control.” Feeling like one is in control of one’s destiny is better than feeling like the product of fate’s cruel vicissitudes. But, as Sandel notes, the flip side of this is that “the more we view ourselves as self-made and self-sufficient, the less likely we are to care for the fate of those less fortunate than ourselves.” We made it out of our own girl-power grit and gumption, so why can’t others do the same?

Over fifty years ago, a 23-year-old copywriter named Ilon Specht devised the tagline “Because you’re worth it” for L’Oréal. No small amount of think pieces since have commemorated its “poignant” and “empowering” message. Global Brand President Delphine Viguier-Hovasse declared that she is not “just managing a beauty brand, [but] managing a brand that supports women to be confident in their self-worth.” Over a hundred years since its founding, the company wants “women to have a seat at the negotiating table in every field: economic, artistic, educational, scientific, political.” Surely this is admirable. But a beauty brand that packages merit in mascara cannot confer worth to women. And representation—a seat at the table—is not the same as fundamental change.

The rhetoric of worth and deservingness, whether in advertising or political punditry, falsely claims to affirm our value while actually suggesting that a minority of us (among whom happen to be “you”) are in the moral elect, the group that has earned status and luxury through hard work and merit. When this rhetoric disguises itself as feminism, it is even more insidious, wrapping self-interested pursuits in the illusion of solidarity. But there is no such thing as a woman who is worth it versus a woman who is not; no human being uniquely deserves “life’s prize,” as Reagan put it, more than anybody else. When we veer toward this thinking, however beautifully virtuous it might make us feel, we fall prey to a host of assumptions that lead us to accept an ugly status quo.