Socialist Politics are More Necessary Than Ever

Though we are smeared as “kooky,” “ridiculous,” and “reprehensible,” socialists are actually the only political actors offering a vision of a future worth living in.

Socialists are used to having a lot of mud flung at us. To be a socialist is to be accused of being totalitarian, utopian, delusional, and even anti-American. One learns to brush this stuff off and move on. Critics of socialism usually do not try to understand the actual positions of socialists. They have done little reading on the subject and demonstrate almost no familiarity with the literature of the left. They attribute to us positions we do not hold, and then explain why those invented positions are ridiculous. Instead of treating socialists as useful citizens, which we are, critics treat us as the enemies of reason. This has been going on for as long as socialism has existed, the tactics the same from generation to generation. The contemporary American right, always in need of useful bogeymen to terrify the public in order to maintain the economic status quo, has declared that socialism is a hostile internal enemy to be destroyed.1

To attempt to respond to every bit of nonsense said against socialism would be a full-time job. I have done my best to address the major arguments in my books Why You Should Be a Socialist and Responding to the Right (forthcoming, pre-order now!) as well as in articles like this 9,000 word response to the National Review’s special socialism issue, this 16,000-word review of Rand Paul’s The Case Against Socialism, this 6,000-word review of Dinesh D’Souza’s United States of Socialism, and other response pieces. In a society governed by reason, my patient refutations would have settled the matter. Yet attacks on socialism persist, and I am reluctantly forced to the conclusion that reason may play only a limited role in American political discourse.

The latest broadside against the socialist worldview comes from economics blogger Noah Smith, who has written an article called “The American socialist worldview is totally broken.” Smith attacks socialists over both their foreign policy analysis and their domestic policy agenda, and suggests that the American socialist movement is embracing “ridiculous” and “reprehensible” positions that will lead us to be a marginalized “kooky fringe” forever. The charge is a serious one, so let us deal with it carefully.

Is The Left Wrong on Foreign Policy?

Smith begins his argument by attacking eminent linguist and foreign policy analyst Noam Chomsky over comments Chomsky recently made about the war in Ukraine on the Current Affairs podcast. Chomsky argued that the U.S. is not doing enough to bring about peace in Ukraine, and said that this country should be pushing for a diplomatic settlement. Chomsky said that it appears the U.S. government might even wish to prolong the war in Ukraine, because a never-ending quagmire would weaken Russia. He cited Zbignew Brzezinski’s admission that the U.S. tried to draw the Soviet Union into Afghanistan to give it a Vietnam-like disastrous war, and noted recent comments from Hillary Clinton indicating that some U.S. policy-makers may be hoping for something similar in Ukraine. Chomsky said that the humane alternative is for the U.S. to try to broker peace as soon as possible.

Many people on Twitter got upset about Chomsky’s comments, to the point where his Current Affairs interview was even a “trending topic” on the platform. A number of commentators, including Smith, voiced outrage at Chomsky’s comments, saying that he was instructing Ukraine to “surrender.” In his article attacking socialism, Smith elaborates:

The arrogance of this kind of armchair quarterbacking is breathtaking — an American public intellectual dictating territorial and diplomatic concessions to Ukraine. Chomsky uses the word “we” to describe the parties that he imagines will make these concessions to Russia, but the first person pronoun is totally unwarranted — it is 100% Ukraine’s decision how much of their territory and their people to surrender to an invader who is engaging in mass murder, mass rape, and mass removal to concentration camps in the areas it has conquered. It is 0% Noam Chomsky’s decision.

As Ben Burgis explains at The Daily Beast, the idea that Chomsky was advocating for Ukraine to “surrender” is absurd. Nor does he take Putin’s side in the conflict, which he called an act of aggressive war and “criminal stupidity” that serves nobody’s interests (except maybe those of U.S. weapons companies). Chomsky explicitly praised Ukrainian president Zelensky and the Ukrainian resistance to Russian aggression, and has endorsed U.S. material support for Ukraine. What he argued is that the war could drag out interminably, like the war in Vietnam or the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, or it could end with a negotiated settlement, and like any settlement of a conflict it will probably involve some unsatisfying concessions.

We should be able to agree, then, that Chomsky’s substantive point about the possible paths the war can take is perfectly reasonable. But the other objection that Smith and many others made is that Chomsky is making Ukraine’s decisions for them. It is not the place of Americans to say how the conflict ought to be resolved. They are not our concessions to make, for this is not our war.

But there is simply no avoiding the fact that the United States is already making policy choices that are deliberately calculated to influence the course of the war in Ukraine. We are spending billons of dollars funneling weapons into this war to influence its outcome. As socialist writer Freddie deBoer wrote in a blistering response to Smith, “calls for the United States to deepen its involvement in this conflict are definitionally the business of each and every American.” Veteran U.S. diplomat Chas Freeman explained that the U.S. has made a choice not to be “part of any effort to end the fighting” or to attempt mediation, preferring weapons aid. (A policy that U.S. weapons companies are thrilled by, incidentally.) Chomsky’s critique is that we appear to be making our current policy choice not just because we want to help Ukraine, but also because, from our self-interested perspective, ending the war is not a priority.

In fact, a long war may be preferable to a short one because it would further weaken Russia, which the U.S. has openly admitted is one of its goals. The Biden administration has declared that “we want to see Russia weakened to the degree that it can’t do the kinds of things that it has done in invading Ukraine,” which the Guardian notes “suggest[s] that even if Russian forces withdrew or were expelled from the Ukrainian territory they have occupied since 24 February, the US and its allies would seek to maintain sanctions with the aim of stopping Russia reconstituting its forces.” This “strategy shift” means the Biden administration wants to go beyond ending the war in Ukraine and appears to want to use the war to hobble Russia’s military power entirely, an extreme goal that the New York Times says “is bound to reinforce President Vladimir V. Putin’s oft-stated belief that the war is really about the West’s desire to choke off Russian power and destabilize his government” and means the U.S. government is “becoming more explicit about the future they see: years of continuous contest for power and influence with Moscow that in some ways resembles what President John F. Kennedy termed the ‘long twilight struggle’ of the Cold War.” The Times notes that this strategy of deliberately turning the war in Ukraine into a broader power struggle with Russia “carries some risks,” something of an understatement given that even the administration admits a U.S.-Russia war would be “World War III.”

Indeed, an extraordinary article in the Washington Post reports the “awkward reality” that “for some in NATO, it’s better for the Ukrainians to keep fighting, and dying, than to achieve a peace that comes too early or at too high a cost to Kyiv and the rest of Europe.” (emphasis added) The article notes that NATO countries do not think it is purely up to Ukraine to decide when and how to end the war. Indeed, the headline is: “NATO says Ukraine to decide on peace deal with Russia—within limits.” (Again, emphasis added.) In other words, how and when to end the war is completely Ukraine’s choice—unless they make the wrong choice.2 This is because “some NATO allies are especially cautious about ceding Ukrainian territory to Russia and giving Russian President Vladimir Putin any semblance of victory.” But why is it NATO allies who should determine what concessions Ukraine ought to make?

The ugly truth, noted by Chomsky, is that the United States does not care about Ukraine out of a principled belief in standing up for the world’s victims against aggression. We ourselves claim the right to invade and destroy any country we like, with immense civilian casualties that simply go ignored in this country. We have a long, long history of wreaking violent havoc and doing nothing to repair the damage or compensate the victims, and could not care less about Palestinian or Yemeni victims of terror. We support Ukraine because it has been attacked by Russia, a rival power. This does not mean that weapons aid to Ukraine shouldn’t be given, but it does mean that the U.S. has an interest in helping Ukraine that goes beyond simply caring about human lives, namely the interest in weakening a strategic competitor. Undermining rival powers is explicitly part of U.S. national policy. James Mattis, in delivering the 2018 National Defense Strategy, stated directly that “great power competition—not terrorism—is now the primary focus of U.S. national security” and the Defense Department’s “principal priorities are long-term strategic competitions with China and Russia.”

Anyone who thinks the “Chomsky point” pays insufficient attention to Ukraine’s needs and desires, then, has it completely backwards. The argument is precisely that we should act in the interests of Ukraine rather than using Ukraine for our own geostrategic ends. Chomsky quotes Chas Freeman saying our present policy is that we are willing to “fight to the last Ukrainian,” i.e. we will not try to end the war, but we also will not fight it. We could be proposing a peace framework to try to minimize damage to Ukraine. Instead, we are making it more difficult to achieve a negotiated peace by being coy about the conditions under which sanctions on Russia would be lifted. As James Acton of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace noted, “this ambiguity is dangerous because it risks obscuring the existence of an off-ramp for Putin.” If the U.S. won’t lift sanctions until Putin stands trial for war crimes in the Hague (war crimes trials, like helping victims of aggression, are something else that we suddenly believe in solely because believing in them has become convenient), then we are disincentivizing Putin from ending the war, by making it clear that punitive sanctions will probably remain in place regardless of whether he withdraws or not.

Smith believes that the socialist take on foreign policy is “that the world’s wars are caused by U.S. imperialism driven by manufactured consent and the greedy military-industrial complex.” This caricature is based on a misunderstanding of our position, though it is an easy mistake to make if you don’t care to spend any time understanding that position. (For a thoughtful introduction to the basic left foreign policy stance, one can read this Jacobin conversation between two of the millennial left’s foremost foreign policy thinkers, Bernie Sanders adviser Matt Duss and foreign relations historian Daniel Bessner. The late Michael Brooks was also an intelligent and valuable commentator on foreign affairs whose insight is much missed.) Critics of the left call us things like the “Blame America First” crowd or say we attribute all the evil in the world to the U.S., or we deny the agency of other actors on the global stage. But this is not the case. First, the reason U.S. leftists talk primarily about the responsibilities and crimes of the U.S. is the same reason that Russian dissidents talk about the crimes of Russia: it’s our country, and is the one whose policies we have some measure of say over. This was a point that Chomsky once tried patiently to explain to a young David Frum, who thought Chomsky didn’t care about the misdeeds of other countries. It was not that Chomsky thought other countries did not perpetrate evils, but that our own evils are the ones we are especially responsible for.

The world’s wars have many causes. But the United States, as the country whose “economic and military power remains unmatched by any other global actor,” has a major effect on what happens in the world, and we are frequently oblivious to how our actions look through the eyes of others. Nor does the U.S. media pay nearly as much attention to victims of U.S. crimes and the crimes of our allies as it does to the crimes of rivals and enemies. Interestingly, this is the point Chomsky was making in a quote Smith cites to discredit him, in which Chomsky critiqued the U.S. media for “emphasizing alleged Khmer Rouge atrocities and downplaying or ignoring the crucial U.S. role, direct and indirect, in the torment that Cambodia has suffered.” Smith criticizes Chomsky for “playing down the Khmer Rouge’s culpability in the Cambodian Genocide.” It’s true that Chomsky was too slow to recognize the full extent of the Khmer Rouge horror, but what Smith leaves out is that a far worse and longer act of Cambodian genocide denial was perpetrated by the U.S. government itself. Zbignew Brzezinski said that while the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime was in power, the U.S. “encouraged the Chinese to support Pol Pot” and “winked, semi-publicly” at Chinese and Thai aid to the Khmer Rouge. Henry Kissinger said when the Khmer Rouge came to power “we will be friends with them. They are murderous thugs, but we won’t let that stand in our way.” After the Pol Pot regime was overthrown and the scale of the atrocities became undeniable, the U.S. still backed the Khmer Rouge for a seat at the UN, the U.S. “opposed efforts to investigate or indict the Khmer Rouge for genocide or other crimes against humanity,” and until 1989 “all attempts even to describe the Khmer Rouge regime as genocidal were rejected by the United States as counterproductive to finding peace.” This was entirely for ruthlessly strategic reasons: the U.S. saw the Khmer Rouge as convenient allies because they were opposed to the government of Vietnam, which had ousted them from power.

This is all separate from the fact that the only reason the Khmer Rouge came to power in the first place was that the relentless U.S. bombing campaign against Cambodia (never called a genocide, because genocide is what others do, and our motives are pure) drove victims to support the Khmer Rouge. As genocide historian Ben Kiernan notes, Pol Pot’s “revolution would not have won power without U.S. economic and military destabilization of Cambodia.” The Khmer Rouge “used the bombing’s devastation and massacre of civilians as recruitment propaganda and as an excuse for its brutal, radical policies.” Kiernan, who extensively documents the human toll of US bombing, says the “carpet bombing of Cambodia’s countryside by American B-52s” was “probably the most important single factor in Pol Pot’s rise.” The point Chomsky makes in the quote Smith cites is that the American press is interested in what the Khmer Rouge did but not in the catastrophic human suffering wrought by our own bombs, or our own role in bringing the situation about (or in supporting the Khmer Rouge after they fell).

This is history Americans are not taught, and it’s appalling. So if socialists are often heard talking about U.S. crimes, it is because people here do not understand how their country uses its power and what the human consequences of that use of power are. Smith, bizarrely, charges that left foreign policy critiques are an “attractive wedge issue that socialists can use to denounce establishment Democrats.” I, for one, do not see foreign policy as an “attractive” issue at all—in fact, it’s almost impossible to get Americans to care about it. We talk about it because the U.S. claims to decide foreign policy on the basis of enlightened liberal humanitarian concerns, but in fact largely decides it on the basis of self-interest, and the results are often devastating for those whose lives are inconvenient or irrelevant to U.S. self-interest. This is not an argument that other countries do not have agency. To say that the U.S. bears some responsibility for the present situation in Ukraine does not diminish Putin’s own responsibility.3 The left’s critiques of U.S. foreign policy are grounded in facts about the record of U.S. actions, and it’s telling that instead of refuting those facts, our opponents make silly, emotionally-charged accusations like telling us we “want Ukraine to surrender.” Smith says that the left believes “anyone who opposes America can’t be all that bad, even if it’s a rightist dictator like Putin,” even though socialists he cites like myself and Chomsky have said nothing in defense of the Russian government, and we loathe autocrats and gangsters like Putin.

I grew up in the Bush years when critics of U.S. actions were persistently accused of Hating America or wanting the enemy to win. If you criticized the U.S., you must believe Saddam Hussein ought to be in power. That sort of brainless rhetoric corroded our ability to have a sensible conversation then, as it does today.4

Is the Left Wrong on Domestic Policy?

Smith’s problems with socialists extend into the domestic realm. He agrees that there are good reasons why in our deeply unequal country we need an egalitarian political movement. But he says socialists are peddling fantasies.

Take, for instance, Medicare For All. Smith says that “the nation was not in the mood” for this “dramatic and extreme” plan, hauling out a familiar dishonest talking point: the argument that “when the specifics of the plan [are] explained,” public support for it drops. “Explaining the specifics” always means something like “framing it as terrifying and radical.” It does not consist of explaining carefully the benefits people would get, the costs they would pay, and showing them how similar systems work. It consists of things like saying “private health insurance would be abolished,” without showing people the ways in which private health insurance is fleecing them. Smith calls Medicare for All “extreme,” which it is not. Even the British system of fully nationalized hospitals is not “extreme,” since government provision of free medical services is akin to government provision of police and fire services—which are never spoken of as extreme. Smith does not respond to any of the clear arguments for why Medicare For All is a good policy, such as those laid out by health policy experts Abdul El-Sayed and Micah Johnson in Medicare For All: A Citizen’s Guide (which as far as I can tell, has barely been reviewed anywhere, because Very Serious Policy Types are uninterested in engaging with a very serious policy argument if it’s made in favor of something “extreme”). Nor does he explain why our current system, which makes human sacrifices to preserve corporate profits, should not itself be considered extreme. As usual, the substantive policy issues are ignored in favor of cheap talking points and empty rhetoric.

Smith also attacks the left over housing policy, lumping many of us into a category he calls “Left NIMBYism.” NIMBY, of course, stands for Not in My Backyard, and refers to those who oppose important building projects for their communities for reasons of narrow self-interest. Smith says that socialists are NIMBYs because we “have embraced the theory that building more housing increases rents and causes gentrification.” He says this idea is “silly” because “if you don’t build houses for people, they won’t have anywhere to live.” Indeed, it would be a silly idea to say that nobody should build houses, which is why I’ve never heard a socialist say this (and why Smith quotes no socialists saying it). In fact, if you turn to socialist policy writers, what you in fact see is plans to build more housing—except with an emphasis on houses that working people can afford, rather than hideous, wasteful new luxury condo towers, opposition to which does not make you a “NIMBY.” (Smith also takes a swipe at my argument that we should consider building new cities, calling it “farcical,” but surely my belief that we should build entire new cities proves Smith is wrong to say socialists oppose building houses, since cities are known to contain houses.)5

What we have so far on the domestic front, then, are two classic anti-socialist techniques: (1) presenting a reasonable, popular policy as extreme, unworkable, and beyond the boundaries of what the public wants and (2) distorting the socialist position to imply it is something different to what it is (“building houses is bad”). The remaining attacks are of similar poor quality. Smith goes after the idea of “degrowth” as an example of the left’s tendency to “embrace faddish intellectual cults offering magical solutions.” He does not attempt to prove his case, but does say that degrowth means we “must address climate change by radically curtailing living standards.” Elsewhere he has said that degrowth means “people in rich countries must accept absolutely catastrophic declines in their living standards.” Now, I am no scholar of degrowth, but I reviewed a book on it once by a leading degrowth proponent, Jason Hickel, and he was at pains to debunk this misconception, and show that the degrowth agenda was actually about improving living standards for all people, by making sure that the world’s resources are not wasted and are put toward improving lives through, say, building hospitals, rather than toward worthless economic activity like mining cryptocurrency and building mega-yachts. The argument laid out in Hickel’s book Less Is More was that conflating living standards with “growth” was a mistake, and that what we should measure is quality of life. This, then, appears to be a case of failing to engage with the literature one is critiquing, which we can also see in Smith’s comment that he is “pessimistic about the degrowth movement switching to a Green New Deal sort of investment-oriented framework.” It is hard for me to reconcile that with Hickel’s statement that “we absolutely need a Green New Deal, to mobilize a rapid rollout of renewable energy and put an end to fossil fuels.”

Smith has a few more claims against socialists, including arguing that, contrary to the left’s analysis, the U.S. is not an oligarchy. Given that the world’s richest man, a demented megalomaniac, has just single-handedly bought the 21st century public square, and this insane, petulant, autocratic individual’s whims will now determine who speaks and how much, I see this as too laughable to even merit further refutation. If complete individual dictatorial ownership over the means of public speech does not mean one lives in an oligarchy, it strains the imagination to picture the kind of dystopia it would take to qualify as one.

Critics of socialism pose as serious and pragmatic analysts, but they consistently decline to do much reading or engage us charitably. Convinced they understand our positions, they attack the cartoon socialist who lives in their head. They tell their audiences the most egregious lies about our positions, and they ignore facts inconvenient to their narratives. This has been the same for as long as socialists have been around making our devastating and rational criticisms of capitalist society.

These vicious, unfair attacks on the socialist position are abhorrent because socialists are doing work that is vital to securing a safe future for humanity. It is the socialists who are most vocally pushing for serious climate action while Democrats dither, and who are always pointing out that half-measures are simply not enough. It is the socialists who are trying to get the U.S. not to lapse into “war fever” once again, and to take us off the path toward a Third World War. It is the socialists who are proposing serious plans for how to fix American healthcare, and build social housing. All around the country, socialists in elected office are doing important work improving their communities, and instead of calling them kooks and fantasists, and trying to discredit them, one should appreciate their hard work and cheer them on. If humanity is going to have a chance of making it, we’re going to need socialists.

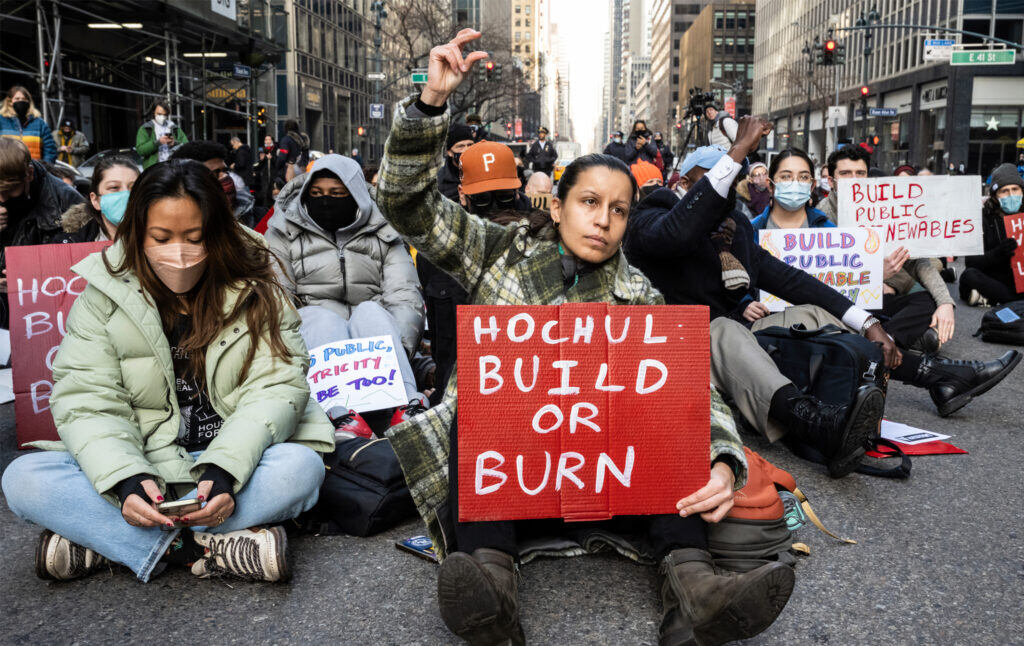

PHOTO: From the Associated Press: “Democratic Socialists of New York and Climate Activists Hold Mass Climate Rally. Holding a sign calling on Governor Hochul to include the Build Public Renewables Act in the executive budget, newly-elected councilmember and Democratic Socialist Tiffany Cabán joins a climate mass rally outside the governor’s office in New York, NY, on Jan. 13, 2022.” An example of the kind of political action that is vital to securing a livable future, which socialists are at the forefront of. The critics of socialism ignore this essential work and do not participate in it, preferring to explain to the left why we are “kooky.”

Republican senator Rick Scott’s GOP agenda calls socialism a “foreign combatant,” a position that, if intended seriously, could justify hideous future repression of the left worse than anything from the McCarthy era. Centrists who choose to spend their time bashing socialists, echoing the right’s ridiculous talking points, rather than defending us against this kind of terrifying authoritarian political movement are showing just how misplaced their priorities are. ↩

International relations scholar John Mearsheimer—who famously predicted in 2014 that NATO’s attempts to court Ukraine without actually offering it the security that comes with NATO membership would lead to Ukraine “getting wrecked”—believes that “If the Ukrainians decide to cut a deal and allow Russia to win in some meaningful sense, the Americans are going to say that’s unacceptable.” Mearsheimer thinks we would go as far as deliberately destabilizing Zelensky’s government to prevent a deal we perceived as too conciliatory. That’s speculation, of course, but anyone who thinks such underhanded tactics would never be deployed by the U.S. has never read the history of U.S. foreign policy. ↩

Some believe that responsibility should be thought of in percentages, and thus if the U.S. bears some responsibility, Putin must bear less. We need not conceive of responsibility this way. A suicide bomber is 100% responsible for their actions, but it can nevertheless be the case that the U.S. bears some responsibility for the suicide bombings in the wake of our invasion of Iraq. Trying to divvy up responsibility as if it is a pie is futile. ↩

One more response on foreign policy: Smith singles me out personally at one point, arguing that I exemplify a “repellent” extreme left view. He cites a critique I made of an article he wrote advocating increasing military spending. Smith argued that the U.S. should be planning its military budget as if we are trying to make sure we would win a Third World War against China. I said this was “planning genocide,” because any such Third World War between nuclear armed states would involve intentionally massacring millions of people—Smith himself proposes that perhaps a billion people would die in the war. In the U.S., planning nuclear wars is not often discussed as planning genocide, but as Daniel Ellsberg notes in his book The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner, this is precisely what nuclear weapons are for. I personally find the idea of figuring out how we could murder a colossal number of Chinese people to be unconscionable. Smith calls it deterrence, I call it planning and threatening genocide. Readers can judge which stance they find more “repellent.” Either way, Smith’s statement that I called “U.S. defense spending” as a whole, rather than Smith’s particular horrifying plan for defense spending, “plotting a genocide” is pure misrepresentation and would be retracted by any honest interlocutor. ↩

Socialist San Francisco city council member Dean Preston has responded here in Current Affairs to the charges that the left is “anti-housing.” ↩