Of Towers and Toilets: A Tale of Two Developments

Developments in Florida and Illinois show how land is valued only as capital. What if we thought of land use differently?

Sometime in 1972, Bob and June Melton moved from Illinois to what they believed would be the lovely new township of Rotonda, Florida. Eager to finally escape brutal midwestern winters, they had bought a house sight unseen for what seemed like an exceptionally reasonable amount. When they arrived, they discovered that their new home was nowhere near finished and that they would have to stay in a condominium for months while the house was still being built. One day, June Melton visited the site to check on its progress. What she found startled her: workmen were installing a toilet bowl in the middle of a doorway.

The bowl was not in the middle of the door to the bathroom. It was not next to the doorway. It was in the middle of a doorway that had nothing to do with the bathroom, an un-bathroom doorway, if you will, through which people would have to walk to get to other parts of the house. When Melton complained, a workman replied, presumably with a shrug, that it was “low enough to step over” (the words drip with shrugginess).

The Meltons’ ordeal is recorded in Jason Vuic’s Swamp Peddlers: How Lot Sellers, Land Scammers, and Retirees Built Modern Florida and Transformed the American Dream, a deeply detailed history of Florida land “development” (as we will see, the word in this context positively quivers and shakes with irony). The book exposes the land scams that went into making the Sunshine State what it is today. Starting in the 1950s, developers created an “installment land sales industry” and began selling pieces of land to northerners for as little as $10 down and $10 a month. The money was to go towards homes in rapidly developing planned communities with futuristic names like Rotonda and aspirational ones like Port Charlotte (not near a port but a harbor), Cape Coral (not much coral), and Palm Coast (very few palms, mostly swamp and pines).

What most people got instead were houses that were barely put together with spit and glue. Vuic cites the author Jack Alexander writing about “crooked lines, walls without framing, slabs poured and houses built with garages on the wrong side, and roofs that hadn’t been fastened to the walls, bad in any case but lethal in a storm.” All of this went on for decades, aided by a complex nexus of corrupt politicians, greedy developers, and credulous consumers, many of whom sank lives’ savings into un-homes. The words “raw sewage” often crop up in Vuic’s account—as it did in or near various allotments.

Fifty years later, in 2021, a segment of Chicago’s Jackson Park—one of the last remaining jewels of public parkland designed by Frederick Olmsted and Calvert Vaux (also the designers of New York’s Central Park)—is being ripped up in order to make way for a 235-foot tall, 20-acre Obama Presidential Center (OPC), in partnership with the University of Chicago. The project and the university are located in Chicago’s historically Black and mostly underserved South Side. For the past six years, the OPC has faced numerous legal challenges. Complainants have pointed out that, among other things, it could easily have been located in any one of several nearby neighborhoods with vast, empty buildings; it will create massive traffic congestion by closing Cornell Drive (which used to run through the park); and it is largely an engine of gentrification. The park has had landmark status, but the city has leased the area to the OPC for 99 years for $10 (it appears that ten is the magic number in land scams).

The OPC’s precise function is unclear. While many assume that it will be the Obama Presidential Library, it is in fact becoming an un-library. It will not have resources for researchers, not even documents Obama’s administration has made public—except those it borrows occasionally from the National Archives and Records Administration, the federal agency that oversees presidential libraries and museums—and then only for display. The Obama Foundation, the entity that fundraises for the project, will also pay for the digitizing of nearly 30 million pages of unclassified records “so they can be made available online,” according to a 2019 report in the New York Times. Nothing about this process is clear: as far as we can tell, documents related to the Obama administration might as well be hurled into a very deep hole in Alaska. Called a “museum tower” (short museums are so silly and early aughts), the OPC will include, according to the NYT, “a two-story event space, an athletic center, a recording studio, a winter garden, even a sledding hill.”

What else could the OPC house? It may be home to Michelle Obama’s inaugural dresses and any outfits that she deems not worthy of being worn any more. It will, like every other museum, surely house a gift shop which might sell precious one-of-a-kind salad bowls made from the wood of trees decimated in the construction process (a view of this outrage is hauntingly captured in a photograph in the South Side Weekly photo essay, “Remembering the Jackson Park Trees”).

What is the point of the OPC? A 2018 FAQ document released by the University of Chicago (and since yanked from the web, available only on Wayback) claims that it will bring 800,000 visitors to the area each year. If you build it, they will come. The OPC also claims, through spokespeople like Valerie Jarrett, that it will generate “$3 billion in economic activity for the city through construction and its first decade of operations.” The Foundation claims it will create 5,000 jobs, though the FAQ only claimed 1,500, and most of these are likely to be the temporary sort, to do with contracting and construction work on the building itself. While such are not to be sneered at (and are often well paid and unionized), they are not what drive long-term economic recovery in an area that still faces infrastructure issues like inadequate public transit and access to groceries. At best, there might be long-term jobs with custodial functions. The OPC speaks often of internship and “leadership training” programs but, again, with a persistent lack of specificity. In the FAQ, the University insists that in benefiting the city, “The Obama Presidential Center will be an intellectual resource, a source of great economic benefit, a key addition to the network of civic partners throughout the city, and a catalyst of new opportunities for the people of Chicago.” This is the sort of thing a visiting Space Alien bureaucrat might say to trembling earthlings, seconds before their planet is blasted to bits to make way for a new Interstellar Highway, as in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

Like an errant toilet seeking purpose in a doorway, the OPC as rendered in plans squats uselessly and without windows in the middle of a historic park. Its creators try to justify its existence in any way possible, throwing out meaningless terms to appease both critics and increasingly suspicious supporters: Jobs! Youth Leadership! Training! Opportunity! Opportunities, in the plural! Did we mention the opportunities? Meanwhile, the actual cost for the project has begun to reach stratospheric levels. In August of 2021, days before breaking ground in the park, the OPC revealed that its initial estimate of $500 million for the project had, ah, um, ballooned somewhat. It would in fact need $700 million just to build the building, $90 million “to collect artifacts, design exhibits and prepare the OPC to operate at opening” and “$40 million to operate the center for one year after construction is completed.” What kind of a building takes $40 million to operate? One built by an egomaniac ex-president who thinks that his legacy can only be enshrined by decimating a historic landmark. At that cost, it ought to at least serve as a landing strip for alien ships needing a refueling station.

Though divided by half a century and several miles, the developments in Florida and the southern corner of Chicago are intimately connected. In each case, there is a relentless drive to demolish public land in favor of private enclaves and to render land and life useless unless they can be made to generate capital, which creates unbounded income for the few while the many, human and nonhuman, are displaced or made extinct.

Consider the words of David Axelrod who, speaking to Politico about the onset of the OPC in the park said, “The thing that strikes me is how little used it is. I think this will bring more people to the park, and it will enhance it.” In other words, for Axelrod, the park is underutilized. If only it could become something else: not an actual park unblemished by buildings that could be enjoyed by the residents of a crammed city, but something that would be used more. But what is a public park to be used for if not to give respite to tired city eyes, to give citydwellers a connection to the vastness and complexity of nature without having to leave their jobs and lives behind for days? How is a park little used when its point is simply to exist on its own terms?

Reading his words, I was reminded of a moment in Vuic’s book when he describes a group of developers who came upon the gorgeous scenery of a gulf and saw not immeasurable beauty which, if left unspoiled, might simply bring pleasure to all who gazed upon it but…millions of dollars from home investors. To them, of course, this was underutilized: what use was a beautiful landscape, a breathtaking vista, if it could not be gazed upon from a stunning home created by a celebrity designer for a very, very rich millionaire? Or a hundred?

In 2017, Chris Christie, then governor of New Jersey, ordered all state-run beaches closed during a government shutdown—and then took over Island Beach State Park with family members during the Fourth of July weekend. Aerial photos taken by the Star-Ledger of New Jersey show Christie’s entourage surrounded by miles and miles of empty beach, tiny ants in a vast sandpit for them to play in. The beach, after all, would surely have been underutilized if not for the First Family’s incursion. And so there they were, frolicking on the beach while the rest of the state was left to find means of entertainment and rest elsewhere.

Years ago, when I lived in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood and within walking distance of Foster Beach, someone responded to my critiques of gentrification by telling me that I didn’t deserve to live in the area given my tax bracket. In many parts of the world, city planners carefully arrange housing blocks so that there are no great divergences in income levels among residents within a given neighborhood. In the United States, land is underutilized even when it’s a beautiful, massive public park because only rich and mostly white people deserve the pleasure of spaces that exist for no reason other than to be there. If a neighborhood offers easy access to a lake, it should only be available to those willing to pay a lot for such: not some renter schmuck who lives off a freelancer’s wages. What matters to developers—and Axelrod, like his former boss, is a developer—is that land be of use to them as a source of capital. Their concern is not so much that land is underutilized but that it should not fall into the hands of people who won’t pay for it: it’s not the land that’s useless and without value but the people (and animals) that dare occupy it without capital investments of some sort.

The Obama Presidential Center: An Origin Story

All of this raises the question: why, other than the fact that he’s a massive egomaniac who thinks nothing of decimating valuable and precious parkland, would Barack Obama even have chosen this site in the first place?

Certainly, the OPC is historic because Obama is the country’s first Black president. But it is also historic in a different sense: Obama is the first president to have launched a bidding war in different states for a building to house his legacy. His options were Columbia University in New York, the University of Hawaii, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and the University of Chicago. For some observers (including me), it was obvious that he would choose Hyde Park—not so much because of his or Michelle Obama’s connection to the area (she grew up on the South Side, he began his political life here and once taught as adjunct faculty at the university), but because this neighborhood offers the most possibility for the kind of reckless development that reaps large profits for a few under the guise of building and expanding community resources. And it includes the University of Chicago, which has built up a long and notorious reputation for avaricious gentrification for almost as long as it has been in existence. The South Side of Chicago has suffered from underdevelopment and neglect, but this is exactly why the university has been quietly buying up tracts of land on all sides. Between 2008 and 2014 alone, it bought up 26 properties in the neighborhood of Washington Park (also the name of another Olmsted-Vaux park), once thought to be the site of what was then still (duplicitously) called a “library.” With an $11.6 billion endowment, the university is not lacking for funds.

The process began in 2017 and has been clouded in controversy and a lack of transparency. The OPC, despite being not-a-library, was able to slide into existence without much press coverage because the Trump years focused people’s attention on a man whose spectacular failure as an American president meant that liberals and progressives were unlikely to look too critically at the last one who seemed like a god in comparison. Only in Chicago did people actually scrutinize what the OPC claimed to offer, in a testament to the still-lively historical thread of activism that has long characterized a city that gave us the eight-hour day and the five-day work week. And some of the most vocal critics were people in and around Hyde Park, a neighborhood whose life in the shadow of a university that is now also its biggest landlord and employer has been a long and complicated one.

Mike Nichols—that Mike Nichols, who directed The Graduate and other films—once said of the neighborhood where he met his equally famous comedic partner Elaine May that “Hyde Park is where white and Black unite against the poor.” That’s a brilliant description and summation of the place. Hyde Park is the most racially integrated area in Chicago, but that’s a low bar in a city so racist and segregated that it operates like a plantation. The Chicago Transportation Authority (CTA) deliberately makes it nearly impossible for people from the mostly Black and brown south and west sides of the city to get to the mostly white north side, for instance. Couple all that with a long process of disinvestment in non-white areas, the fact that everyday racism persists at 1960s levels, that majority Black neighborhoods face heightened levels of violence—and it’s understandable that “Black flight” has been persistent for several years now. Hyde Park and some of its nearby neighborhoods like Bronzeville and South Shore have in the meantime long been home to an affluent and middle-class Black population (Margo Jefferson’s famous Negroland: A Memoir is a clarifying account of her life in the area as part of the Black upper class). For them, development is an asset that drives up their housing values and helps to maintain what they see as an exclusive enclave of their own.

While even many Hyde Parkers assume that the neighborhood has always been wealthy, it has in fact historically been home to a mix of classes and races, with a strong segment of working- and middle-class people. It’s only in the past decade or so that the university, which even decides what businesses should exist here, has taken on a much more explicit role in gentrifying the neighborhood, enabled in part by newer local politicians who give in to its demands. In recent years, it has set about building expensive designer apartment complexes for affluent students, their gleaming towers in contrast to the older Victorian and modernist buildings that were more common (the university was explicitly designed, from its inception in 1892, to resemble Oxbridge: like Chicago, which struggles with being the “second city,” it has a massive chip on its shoulder).

Hyde Park has been unique among Chicago neighborhoods in that there have been multi-generational families living here: children who left for jobs or college would return to the place of their childhood and live near parents and grandparents, creating a community whose collective memory is different (and more left-leaning) than most, especially most college towns. That is changing now as rents and housing prices have gone out of range for all but those with substantial wealth: the housing market is currently geared towards wealthy students and faculty and administrators, with rents outpacing those in the rest of the city.

None of this has been a smooth transition, and there have been in recent years several shootings and other acts of violence that threaten to burst the bubble in which many Hyde Parkers have tended to live. In the last month alone, there were two shootings in broad daylight, and one resulted in the death of a Chinese UChicago masters graduate. This was not the first time that an international student had been shot dead. International students, who pay a lot more tuition than domestic students, are an important source of money for the university but also bring international prestige as it seeks to maintain its position as a “world-class” institution.

All of this—along with the world-shattering pandemic—threatens the equilibrium fondly imagined by the Obamas and the university: they clearly conceived of the OPC as the center of, in essence, a massive hedge fund operation. The university has been rapaciously buying up land in order that it might eventually and literally cash in on its investments. The Obamas were to bring the full force of their massive international elite network to the table and act in collusion with an already prevalent and powerful Black elite to thrust out undesirable populations of Black, white, and any other people whose incomes did not match their vision for the larger neighborhood. For instance, the OPC is near the small but delicately beautiful Japanese Garden, created during the 1893 World Columbian Exposition (also known as the 1893 World’s Fair). With its koi pond, herons, pavilion, and a Yoko Ono sculpture Sky Landing just outside its entrance, it’s a perfect place for receptions. It has always been open to the public at any time of day and night. In August, the Chicago Park District installed permanent gates, closed from dusk to dawn, claiming that this was to prevent vandalism and cruising. It’s hard not to imagine, given the timing, that such moves are yet another way for the OPC to slowly encroach upon more public lands to claim them as its own.

Where the Alligators Roam

How do we distinguish between the built and the unbuilt, between nature and artifice? It may seem like there’s a simple answer: brick and mortar constitute the built and artificial, and trees and lakes are of nature as we understand it.

But in fact, those distinctions are not that easy to make, especially in Chicago and especially in the area around the proposed OPC—and even in the gulfs of Florida with its threatened yet still fertile swamplands and natural habitats. Jackson Park was designed in 1871 and then extensively remodeled in 1893 for the World’s Fair: it may comprise objects we recognise as nature, but they were very deliberately planted there in accordance with a man-made plan. Certainly, over more than a hundred years the Park and surrounding areas have become a valuable ecosystem that is home to various species of birds and animals. Certainly, the OPC should have been built or housed in an area which already has several usable buildings—for instance, one or two or more of the fifty Chicago public schools (housed in spectacular buildings) in the area that were closed by former mayor and Obama henchman Rahm Emanuel. But how might we think of matters like development and the use of land without falling into nostalgic ideas about original possession (and without ignoring the fact that, well, all of Chicago is land stolen from the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi Nations and others)?

The archeologist Rebecca Graff has spoken about losing valuable artifacts of the Columbian Exposition to the construction of the OPC, which sits on the old sites. Speaking to Chicago magazine, she marveled at the amount of objects that she had already uncovered:

“Plaster isn’t supposed to last 125 years underground, but with all the columns, it looked like we were doing an excavation in ancient Greece. There were also bits of artifacts from the building: broken plates, pretty little cruet tops from oil or vinegar, buttons—all sorts of odds and ends.”

History isn’t just “ancient” as we understand it: it’s in a constant state of motion, always emerging from the here and now, thrusting itself into the future and the near-present with all the curiosity and eagerness of an ancient tree’s roots slowly working itself back to a surface it has never known but wants desperately to encounter.

In Florida, the 1950s rush to scam as many unwary prospective homeowners has been blunted somewhat by the fact that there is a limit to how much can be bought and subdivided into tiny lots and that even a corrupt state like Florida (Illinois may be its closest rival in the level of corruption) can only allow so much chicanery for so long. In the meantime, several land scammers like the Mackle brothers became, like the Trumps in New York, generationally wealthy and bought themselves respectability. Today, the influence of environmentalists has meant that newer developments are held to greater scrutiny. But even then, the conflicts between the built and the unbuilt continue.

In Babcock Ranch, one of the more recent developments (plans to develop the area from an actual ranch to a city began in 2005), one father faced the conundrum that his elementary-school-aged son and other children in the area would be making their way to school past retaining ponds filled with alligators (part of the ranch’s reservoirs). His solution was to teach the very young child to drive: every morning the boy would load even younger children into the car and drive it up to the bus stop a mile away thus avoiding any four-legged denizens curiously searching for a morning snack.

In Chicago, there are no alligators, but there are frequent shutdowns of lakesides on the south side because of the level of water contamination, something that rarely happens on the north side. The OPC and the Obamas pretend that, somehow, the mere presence of a giant behemoth of a building and all its empty promises of jobs and opportunities will magically transform a city and an area that has, from its inception, been grounded—like the country—in slavery and genocide. The OPC provides the illusion that centuries of neglect can be wished away with a sledding hill and a museum campus devoted to a purpose that no one can divine but which will exist, as conspicuous as if it were in fact a large golden toilet in the middle of the park.

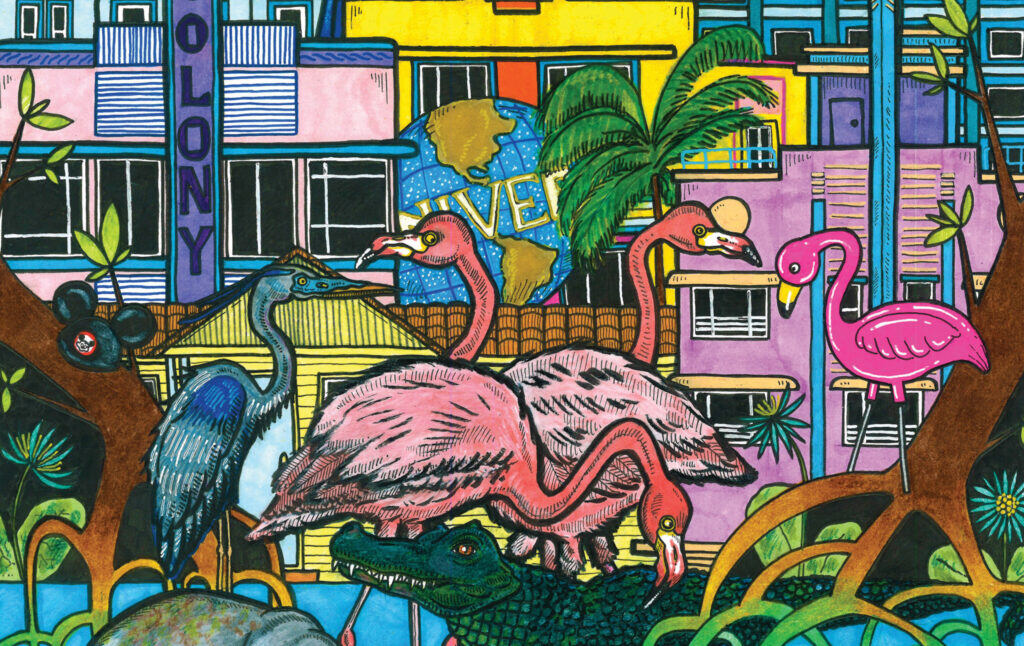

But what if we thought of land differently, in terms of its “use”? Why are we afraid of our children being eaten by alligators when it’s the alligators whose usable areas have been taken away by us? Why not let them eat the occasional child, as a peace offering? Why is it not okay for Southsiders to have vast tracts of “useless” land to walk through? How might we think about swamps in Florida, where alligators and flamingos “uselessly” meander through their everyday lives, being turned into homes so badly constructed that there are toilets in doorways and houses built with their roofs barely attached to the walls? How might we think about land and its “use” differently, without the rapacious forces of brute capitalism?

Yasmin Nair lives in Hyde Park where she frequently walks in Jackson Park, dogless. She’s currently working on her book, Strange Love: The History of Social Justice and Why It Needs to Die, as well as several shorter pieces on the Obama Not-A-Library. Her work can be found at www.yasminnair.com.

For further reading:

- Leonard C. Goodman, “The Obama Center And The Fight To Preserve Jackson Park.”

- Hugh Iglarsh, “The New Ozymandias: Twilight Reflections On The Obama Center.”

- Michael Lipkin, “The Way Things Work: Land Ownership.”

- Kate Mabus, “The University’s Expansion Into Commercial Real Estate Wavers Between Economic Catalyst And Gentrifying Force.”

- Michael Murney, “It’s Not About Obama.”

- Yasmin Nair, “Obama’s Birthday Bash Is For Neoliberal Elites.”

- Rick Perlstein, “There Goes the Neighborhood: The Obama Library Lands on Chicago.”