The Toxic Positivity of Hillary Clinton’s MasterClass in “Resilience”

Clinton’s message is clear: doing well in life is simply a matter of “choosing resilience,” as if it were a lifestyle choice. But steeling oneself against a harsh society is not social justice or a viable political philosophy. The last thing we need is a new generation of vacuous Clintonian politicians.

MasterClass is an online teaching platform where celebrities impart skills and life lessons—often not very well. It has recently introduced a “White House” series of classes by political elites, starting with classes from Hillary and Bill Clinton—who teach “The Power of Resilience” and “Inclusive Leadership,” respectively. (Next semester George W. Bush will be joining to teach “Avoiding Indictment For War Crimes”—uh, “Leadership.”) Hillary Clinton’s MasterClass has made the news because in it, she chooses to deliver the victory speech she would have given had she won the 2016 election.

Current Affairs editors (ourselves and Editor at Large Yasmin Nair) recently watched the full MasterClass and discussed our findings on a podcast episode. For the most part, it is simply dull. It consists of 16 sessions with titles like “Discovering Your Mission,” “Overcoming Setbacks,” and “Daring To Compete.” The Current Affairs staff eventually had to start watching at 2x speed, to get it over with as fast as possible—it may be said for Clinton that she manages to make a few hours of video footage feel like spending an entire semester with her. Clinton dispenses advice so banal and obvious (set goals, stay organized, persevere) that it’s hard to think of who the audience for the course is supposed to be (although we will take a guess shortly). The would-be victory speech is the oddest part of the “class,” and seems more like something Clinton’s therapist recommended she perform as a way of processing her loss than a good faith pedagogical tool. The class lacks focus—sometimes it is a course on public speaking, sometimes it is about negotiation tactics, sometimes it is just about the life philosophy of Hillary Clinton. One session is devoted to an uncomfortable conversation with aide Huma Abedin—uncomfortable because the “resilience” both women have demonstrated in public life is clearly partly about dealing with embarrassing scandalous behavior by their philandering politico husbands, but this elephant in the room goes entirely unmentioned. Clinton and Abedin simply talk in general terms about how to put setbacks aside.

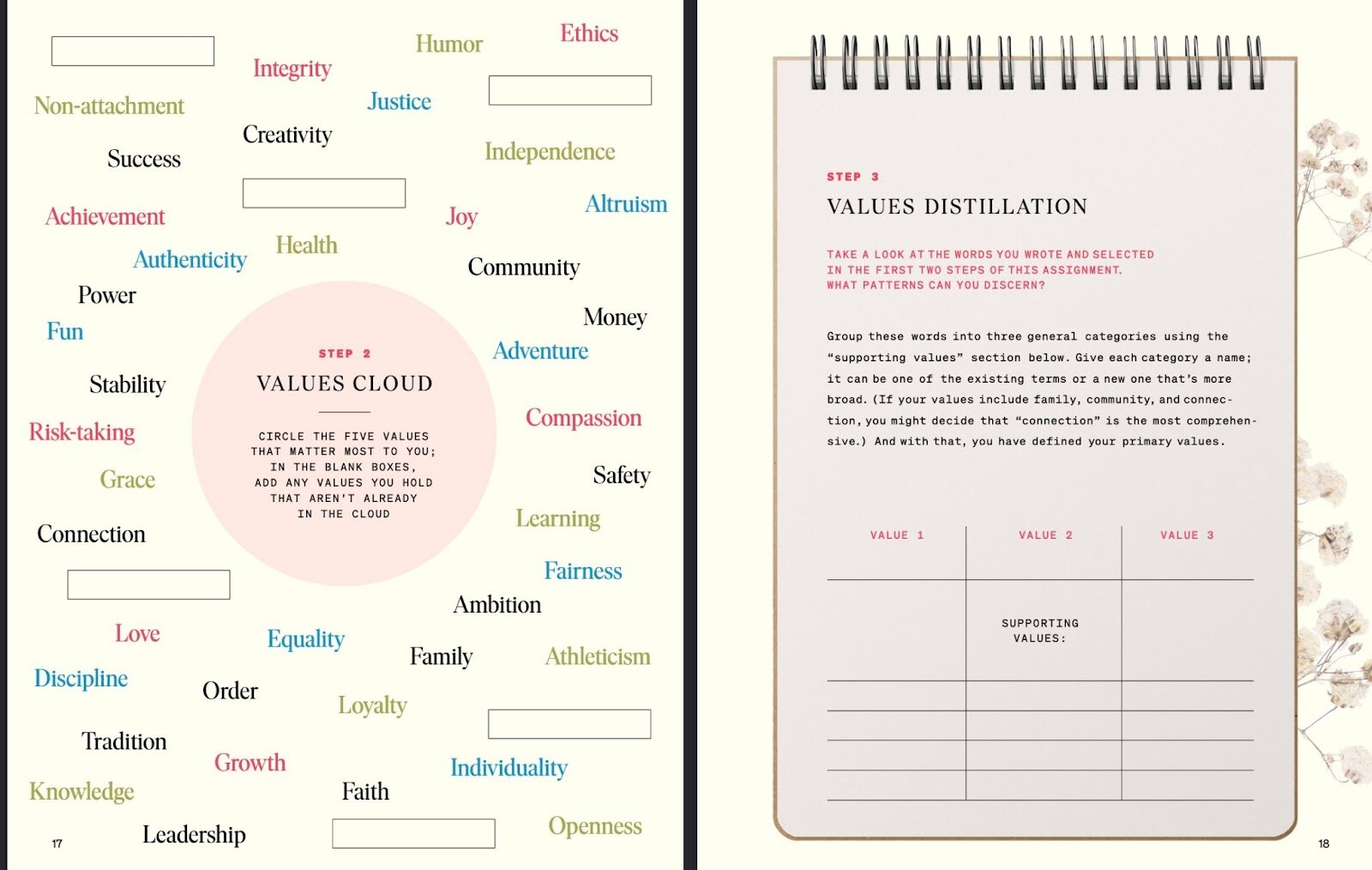

Like the Clinton 2016 campaign, the course stays well clear of saying anything substantive. Its mushy uplifting abstractions would embarrass a corporate motivational speaker. The accompanying course workbook (mostly just a pamphlet about the life and resume of Hillary Clinton) includes a “values cloud” exercise in which people are supposed to pick and choose some values that might suit them. (One of the optional values is “money,” which presumably you’re not supposed to choose, but it’s probably okay if you do.) The class carefully excludes discussion of huge portions of Clinton’s actual record of enacting her values (for instance, she cites the importance of being mentored by children’s rights advocate Marian Wright Edelman without mentioning that Edelman became disgusted with the Clintons over Bill Clinton’s successful effort to gut welfare for needy families). It is partly a motivational speech, but partly an effort to rewrite history and recast Hillary Clinton as a heroic advocate for social justice causes whose life has been inspired by the example of Martin Luther King, Jr.

But even though the course is in part simply a tedious piece of self-aggrandizing propaganda, there’s something pernicious about the underlying philosophy that Clinton tries to impart. The ideas in it are not benign. Clinton frames the course around the idea of “choosing resilience” and the importance of working hard and building character. You can rise to the top and be a Hillary yourself, but only if you are prepared, organized, and diligent. MasterClass sees “politics” as a matter of positive thinking by individuals who ascend the ladder through their adherence to a meritocratic ethic. Clinton’s “choosing resilience” is downright toxic and antithetical to leftist values of solidarity, social justice, and concern for the marginalized and vulnerable in society.

The narrative of individual responsibility, hard work, achieving the American Dream, meritocracy, and self-improvement is widespread and readily accepted in U.S. culture. As sociologist Jennifer Silva quoted Jacob Hacker in her 2013 book Coming Up Short: Working-Class Adulthood in an Age of Uncertainty, “America’s sweeping ideological transformation,” starting in the 1980s with cutbacks in social services and the rise of the free market ideology, promoted a “go-it-alone vision of personal responsibility.” Silva interviewed 100 working-class adults and found an underlying theme in their personal outlooks: that they practiced a kind of “individual risk management” strategy based on their experiences of “betrayal within the labor market [and] institutions such as education and the government” and the understanding “that they are completely alone, responsible for their own fates and dependent on outside help only at their peril.” Clinton herself promotes what is essentially a go-it-alone self-help course targeted, most likely, to middle-class people of the aspiring professional-managerial type.1

In the first lesson, Clinton gives a summary of her early life, from a childhood in which teachers and family encouraged her to her “a-ha” moment of the 60s, which she says inspired her to “be an advocate for children, families, and a more equitable society” so that more people could “live up to their potential.” After summarizing (mostly vaguely) the various political and personal setbacks she has faced, she says that her “values” have enabled her to stand up to forces outside of her. “I choose to keep going. I choose to be resilient,” she declares.

But does one really choose resilience? Resilience is a capacity to rebound after something bad happens, but capacities may differ. One can certainly aspire to be resilient, or try to prepare for bad events that have not yet happened, and do one’s best when faced with adversity. But if we believe that it’s possible to decide to be resilient, are we not implicitly saying that those who don’t rebound after adverse incidents are making a choice?

In a society defined by personal choice, the ability to actually choose something matters. All kinds of choices are presented as true choices when they’re not. Does someone choose to send their child to a poorly-funded or segregated public school if that is all that’s available in their area? Has the child who fails to exert the Herculean effort needed to overcome these circumstances simply failed to show sufficient resilience? Does someone choose a low-paying job if most of the available jobs are low paying? Does someone choose to eat unhealthy food if better food is unaffordable or inaccessible? Does someone choose to work multiple jobs to pay off student loan debt if they were repeatedly told they needed to obtain that education to improve their lives? We could go on and on listing examples of “choices” that aren’t really choices because people make these decisions under conditions of economic and social duress.

In the realm of psychology or mental health, one may not be able to simply choose resilience. For instance, Clinton talks about her mother’s “difficult” upbringing, and how her mother’s resilience inspired Clinton to work hard in life. Clinton says her mother was, at age 8, sent to LA on a train with her younger sister and made to take on a job (“babysitter/housekeeper”) after finishing the 8th grade. “It was not an easy life,” and her mother “overcame2 what to many would have been crushing experiences,” Clinton says.

Indeed, these “crushing experiences” are now recognized as Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). According to the CDC, ACEs are “common” and are “linked to chronic health problems, mental illness, and substance use problems in adulthood.” ACEs can cause “toxic stress,” which describes a variety of harmful effects on the body. While Clinton’s mother’s adverse experiences (child labor included) should not be trivialized, can we say that she really chose to bounce back from ACEs, or, rather, that some combination of individual traits, family resources, and other environmental inputs affected her overall outcome? Furthermore, what about the people who aren’t able to bounce back quite so well from abuse, trauma, neglect, or other adverse experiences? What about those who live with chronic problems or diseases in their lives? Quite simply, Clinton has nothing to say to these people.

To follow Clinton’s idea of choosing resilience to its logical extreme means, ultimately, judging or dismissing others who don’t bounce back. As Silva points out, her interviewees had absorbed such a “rugged individualism” mindset that they drew “harsh boundaries against those who cannot make it on their own.” Those who cannot “‘fix themselves’ emotionally are met with disdain and disgust.” When you judge people for their weakness—for their inability to bounce back—you assign them less worth, and when people become less worthy or unworthy of sympathy, they become neglected or marginalized politically. Disdain for human weakness is a deeply conservative notion that is inconsistent with leftist notions of social justice and of creating a society in which all people’s needs are met, especially the poor and marginalized. In reality, society should treat people who don’t bounce back from adversity with more, not less, compassion and sensitivity. But that’s not the kind of logic we hear from Clinton.3

What about people who aren’t where they want to be in their lives? To people who are unsatisfied with their jobs, for example, Clinton recommends they be “creative and flexible” in finding another job. Or “go start your own thing,” she says, as if starting one’s business is even vaguely an option for the millions who are struggling to get by with low wages and/or debt. (Start one’s own business and get rich—another aspect of the American Dream that is increasingly unattainable.)

Clinton claims her course is for “anyone, at any age, who wants to think about building a life of meaning and purpose, of setting goals, and working toward achieving them, of having a mission that captures your values, what you care about, what you’re willing to stand up for.” If you follow her “Framework for Hard Work” (the title of her 3rd lesson), you’ll do well.

But this sounds like a vapid institutional mission statement, and people are not institutions with checklists. People work hard every day and barely get by, and their “values” are not enough to make their employers pay them more.4 Listening to Clinton’s audio, Lily recalled this passage from Howard Zinn’s You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train:

“All his life he [Zinn’s father] worked hard for very little. I’ve always resented the smug statements of politicians, media commentators, corporate executives who talk of how, in America, if you worked hard you would become rich. The meaning of that was if you were poor it was because you hadn’t worked hard enough. I knew this was a lie, about my father and millions of others, men and women who worked harder than anyone, harder than financiers and politicians, harder than anybody if you accept that when you work at an unpleasant job that makes it very hard work indeed.”

The truth is that Clinton’s course is only for anyone who aspires to be like her, perhaps aspiring political aides or politicians, people who aspire to work within the bipartisan capitalist political structure that is responsible for so much injustice, people who believe that if they were able to “make it” into elite institutions and into political power that everyone else should be able to overcome their own obstacles, too. Clinton’s course is also for people who believe in the myth that society is basically okay and we just need to tweak things.5 But these ideas are not going to get us anywhere if we’re looking for radical change. Clinton’s morally empty politics failed to win in 2016 and are utterly incapable of speaking to a population that is overwhelmingly disgusted with the status quo.

Toxic positivity insists we look on the bright side. But to look on the bright side—in this context, to look only to oneself as a source of “resilience” against a cruel world—is to delude oneself personally and politically into alignment with the status quo. As Barbara Ehrenreich writes in Bright-Sided: How Positive Thinking is Undermining America:

“…positive thinking has made itself useful as an apology for the crueler aspects of the market economy. If optimism is the key to material success, and if you can achieve an optimistic outlook through the discipline of positive thinking, then there is no excuse for failure. The flip side of positivity is thus a harsh insistence on personal responsibility: if your business fails or your job is eliminated, it must be because you didn’t try hard enough, didn’t believe firmly enough in the inevitability of your success. As the economy has brought more layoffs and financial turbulence to the middle class, the promoters of positive thinking have increasingly emphasized this negative judgment: to be disappointed, resentful, or downcast is to be a ‘victim’ and a ‘whiner.’”

Students of Clinton’s MasterClass, then, are not to be “whiners.” They’re also not supposed to think as hard about changing society as they are about changing themselves.

In truth, we can steel ourselves against a harsh society, or we can build a political movement to stop doing the things that create a harsh society to begin with. Our society is harsh because of crises our leaders refuse to address (climate and the pandemic), wealth and income inequality, systemic racism, lack of universal health care, mass incarceration and the policing of poor people and people of color, and stagnating wages, to name a few. By all means, do self-care: try to take care of your physical and emotional health as best you can. But remember that self-care and hard work are not substitutes for social justice or for working to create the kind of society that meets human needs within ecological limits. We need to build solidarity with others who are also struggling. As Silva writes, we need to “foster connection and interdependence rather than hardened selves.” Hillary’s toxic positivity of hyper-individualism is not a viable political philosophy for the left, and we ought to reject these kinds of beliefs no matter who espouses them.

Thomas Frank writes about the meritocratic politics of the “winner” professional-managerial class in Listen, Liberal: Or What Ever Happened to the Party of the People? ↩

Clinton mentions many “setbacks” in her course, including everything from her mother’s upbringing to severe weather events/climate change to people criticizing her out of “one-sidedness” or “meanness.” All negative things collapse under the umbrella of “setbacks,” as if they were merely things to step over, which is a kind of denial or “toxic positivity.” ↩

We will get into Bill’s MasterClass soon, as well as into the details of his disastrous record, but one could argue that, in fact, the Clintons’ overall policy approach has been to respond to poverty, crime, and other social problems with the harshest approach possible. ↩

Unless, of course, people start talking about their values with each other and organizing for better conditions. However, collective action is not a feature of Clinton’s “Resilience” philosophy. ↩

She said in a 2016 presidential campaign debate that capitalism had “run amok,” as if things would be okay if we could simply get it a bit under control. ↩