Adventures in 19th Century Socialism

H.M. Hyndman was a buffoon and bigot who nevertheless left behind a fascinating account of the early decades of radical politics.

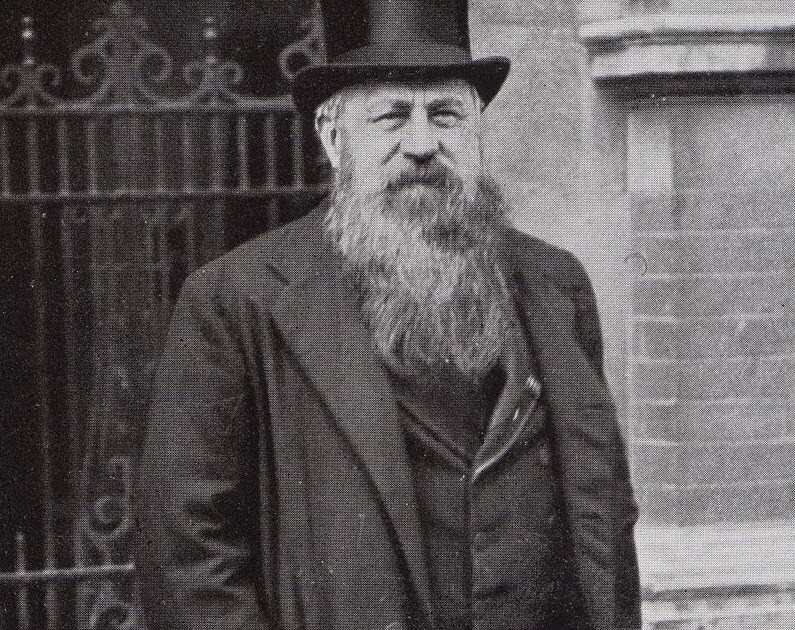

Some of his contemporaries may have argued that the socialist movement would have been better off if H.M. Hyndman (1842-1921) had never shown up on the scene. Hyndman, an Englishman born into wealth who flitted in and out of journalism and business, read Das Kapital while on a steamer across the Atlantic and became one of the earliest British admirers of Karl Marx. In 1881 Hyndman wrote England For All, which was not only the first English-language summary of Marxist ideas, but the first significant socialist book to have been published in Britain for 50 years. (Das Kapital wouldn’t be translated into English for another six years.) Hyndman then founded Britain’s first socialist political party, the Social Democratic Federation, though it remained so small that at least one detractor called it “The Social Democratic Federation, also known as Henry Hyndman.”

Hyndman may have admired Karl Marx, but the warm feelings did not run both ways. Marx and Friedrich Engels saw Hyndman as a bourgeois flibbertigibbet with a thin understanding of socialist economic theory. Hyndman wrote nostalgically of the time he spent with Marx in London, but Marx’s own privately expressed sentiments suggest he had been staring at the clock most of the time: “Many evenings this fellow has pilfered from me, in order to take me out and to learn in the easiest way.” Marx was livid when England For All came out, because while Hyndman wrote that he was “indebted to a great thinker and original writer,” he did not cite Marx by name, and Marx did not accept Hyndman’s “stupid letters of excuse” for the omission. (Hyndman apparently justified himself by saying that “the English don’t like to be taught by foreigners.”) The fraying of the relationship meant that “the only articulate British-born Marxist of the time ceased to be on speaking terms with Marx,” which was not ideal for the cause.

Hyndman’s subsequent reputation among socialists has never been high, to the extent that he had a reputation at all. Vladimir Lenin thought he was an ass, a philistine who misrepresented Marx and preferred “miserable gossip” to analysis. The great designer and poet William Morris, whose News From Nowhere remains one of the most beautiful utopian texts of all time, fled Hyndman’s federation a year after joining it. (This has the proud distinction of being the first schism in the modern British socialist movement.) Today, Hyndman’s Wikipedia entry paints an unflattering picture, emphasizing his infamous anti-Semitism and his managerial incompetence (“Hyndman was generally disliked as an authoritarian who could not unite his party”). The footnotes to the Soviet-edited edition of Marx and Engels’ correspondence describe Hyndman as a man who “pursued opportunist and sectarian policy in labour movement [sic], later one of the leaders of British Socialist Party [sic], from which he was expelled for supporting imperialist war.” Indeed, Hyndman supported British involvement in World War I, alienating his comrades and leading him to form the obscure, doomed (and unfortunately named) “National Socialist Party.” It is impossible for anyone to see Hyndman, pioneer though he may have been, as an inspiring historical role model.

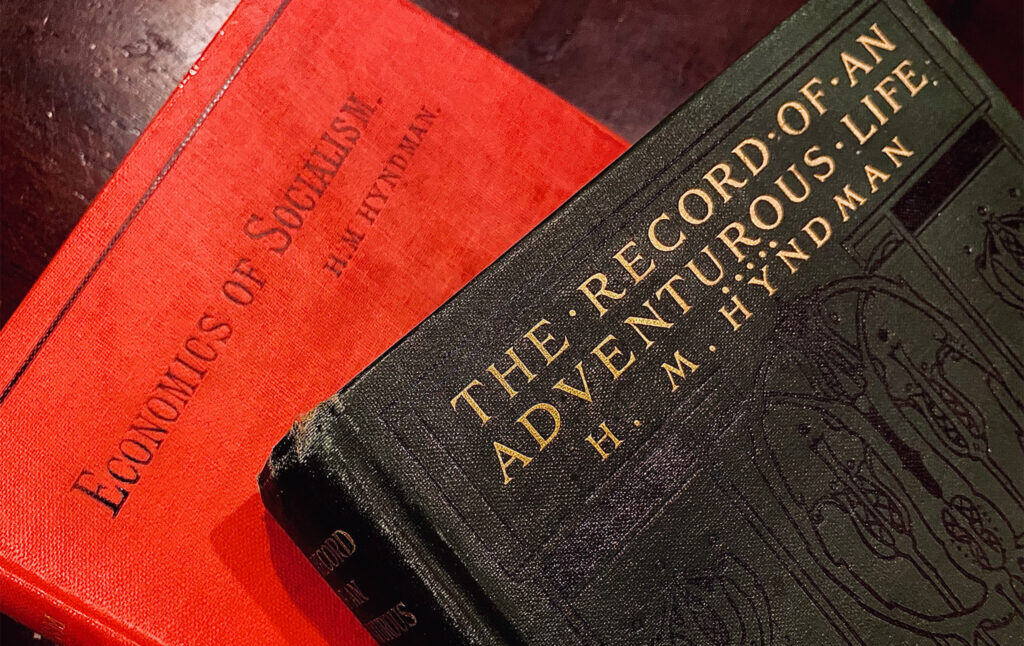

I confess, however, that I am a sucker for out-of-print books by long-dead socialists, and years ago I obtained copies of Hyndman’s two volumes of memoirs, The Record of an Adventurous Life (1911) and Further Reminiscences (1912). They gathered dust until recently. But upon picking them up, I became engrossed, because while the books confirm Hyndman to be everything his critics said—he is utterly insufferable, self-important, prejudiced, and gossipy—they are also a fascinating document of a previous era of radical politics. And, shockingly enough, they contain some useful observations and wisdom that are still relevant in our own time.

Lenin, reading Hyndman’s first memoir, was disgusted by Hyndman’s tendency to list all the celebrities he had met. Indeed, in both books Hyndman cannot help himself from constantly name-dropping. In his defense, however, he has an impressive index of names to drop. Hyndman was the Forrest Gump of 19th century socialism, seemingly everywhere running into everybody of any historic importance. In addition to Marx, Engels, and William Morris, at various points in his memoirs he recounts personally crossing paths with all of the following: Oscar Wilde, Susan B. Anthony, George Bernard Shaw, Clarence Darrow, Henry James, Peter Kropotkin, Sylvia Pankhurst, Benjamin Disraeli, Eleanor Marx, Annie Besant, King Edward III, Henry George, Henry Morton Stanley, Helen Taylor, Georges Clemenceau, Lady Warwick, Giuseppe Garibaldi, George Meredith, Michael Davitt, Frances Willard, Joseph Chamberlain, Aristide Briand, Giuseppe Mazzini, W.T. Stead, John Galsworthy, Keir Hardie, Alfred Russel Wallace, Jean Jaures, Lord Randolph Churchill, August Bebel, Edward Carpenter, Big Bill Haywood, and H.G. Wells. Hyndman says that he once played cricket against the legendary W.G. Grace and that Judah P. Benjamin, the future Confederate Secretary of State, encouraged him to pursue a career in the law. (He didn’t end up becoming a lawyer because “I disliked the idea of battering out my brains over disputes about other people’s property, I took little interest in whether criminals of varying degrees of turpitude were condemned or acquitted, and the atmosphere of the Courts was as unwholesome to me physically as legal shop was unpleasant to me mentally.”) Just about the only personage of the era that Hyndman admits he didn’t meet is Eugene V. Debs. His stories about meeting these people often seem to involve his defeating them in an argument, or being complimented by them on something he has done, or recognizing their genius before anyone else did. It wouldn’t be surprising to find Hyndman writing that Abraham Lincoln was just in the middle of explaining that Hyndman’s views were correct when Booth’s bullet cut him down.

But one shouldn’t conclude that Hyndman fabricated these encounters, and many of them can be verified. Plus, the world was smaller then, and Hyndman was a Cambridge-educated globe-trotting journalist with too much money who lived a long life. In fact, the person on the list he was least likely to have met is one we know for a fact he did meet: Marx. During his final years in London, Marx was living in poverty and obscurity. Das Kapital, as already noted, had not been published in England, and Marx was unknown among the prominent economists and political scientists of the day. Hyndman was fortunate indeed to have stumbled upon the ailing German immigrant whose theories would posthumously ignite revolutions around the world.

Hyndman’s portrait of Marx is unforgettable. As one of the few eyewitness accounts from Marx’s life, it is invariably quoted in Marx biographies. “The first impression of Marx as I saw him,” Hyndman says, “was that of a powerful, shaggy, untamed old man, ready, not to say eager, to enter into conflict and rather suspicious himself of immediate attack.” When he was angered, “the old warrior’s small deep-sunk eyes lighted up, his heavy brows wrinkled, the broad, strong nose and face were obviously moved by passion, and he poured out a stream of vigorous denunciation, which displayed alike the heat of his temperament and the marvellous command he possessed over our language.” Hyndman quickly concluded that Marx was “the Aristotle of the 19th century,” and that “no economic or sociologic contributions to the science of human development can be complete without taking full account of Marx’s profound investigations.”

But the vehemence with which Marx attacked his opponents, in Hyndman’s judgment, kept the “serious” thinkers of the day from seeing how profound his work was: “Marx’s terrible onslaughts with naked steel upon his adversaries appeared so improper that it was impossible for our gentlemanly sham-fighters and mental gymnasium men to believe that this unsparing controversialist and furious assailant of capital and capitalists was really the deepest thinker of modern times.” That anger, however, came from a genuine disgust at the conditions of the working class and the sham arguments used to justify existing abuses. Hyndman writes that “there can be no doubt whatever that his hatred of the system of exploitation and wage-slavery by which he was surrounded was not only intellectual and philosophic but bitterly personal.” Hyndman recalls once saying that as he got older, he became more tolerant. Marx, he said, was incredulous. “Do you? DO YOU?” he replied. “It was quite certain [Marx himself] didn’t,” Hyndman remarks. (Hyndman has no time for Friedrich Engels, a man of “overbearing character and outrageous rudeness,” and holds Engels responsible for the unraveling the Hyndman-Marx friendship, offering a wacky theory that Engels did not want another rich man hanging around Marx, lest it end Marx’s dependence on Engels’ largesse.)

Other radical leftists of the time are also drawn vividly. IWW leader Big Bill Haywood “genuinely hates the men in possession in all countries” and was “an extremely powerful figure with a clean-cut, clean-shaven face,” “cool, friendly, and urbane,” “not, as a rule, vehement or eloquent.” Yet “the loss of one eye gives him almost a sinister appearance” and “when he gets on a topic that really stirs his feelings it is easy to see that he is not one of those who, at a critical period, would allow any fear of consequences, or even the opinion of those around him, to deter him from taking the course which he felt was necessary to ensure success.”

Hyndman also colorfully brings to life William Morris, in the period before Morris, too, grew sick of Hyndman (a quarrel for which Hyndman refuses to accept any blame, saying that “the influence which brought about the split at the end of 1884 was the malignant lying of a despicable married woman, whom none of us knew well, on a purely domestic question,” though declining to elaborate):

I always recall him in that blue tweed sailor-cut suit which someone unkindly said made him look like the purser of a Dutch brig. But you very soon forgot all about his rough clothes or his soft hat when he began to talk upon any subject which interested him. His imposing forehead and clear grey eyes, with the powerful nose and slightly florid cheeks, impressed upon you the truth and importance of what he was saying, every hair of his head and in his rough shaggy beard appearing to enter into the subject as a living part of himself. His impulsive, forcible action, allied to an admirable choice of words, gave almost a physical force to his arguments, which was not lessened by the sturdy vigorous frame from which they proceeded.

When Hyndman met Kropotkin, the great anarchist philosopher and zoologist, “I was at once captivated by the charm of his manner and the unaffected sincerity of his tone,” but he was frustrated when he “tried to argue with [Kropotkin] about his Anarchist opinions, which seemed to me entirely out of accord with his intelligence and naturally charming disposition.” Hyndman says he tried to point out that while Kropotkin rejected all authority, he was himself the editor of a newspaper. “Who decides as to what should be put in and what should be kept out?” “Why I do, I am the Editor,” Kropotkin replied.” “Then Kropotkin,” Hyndman recalls saying, “you are no better than a tyrannical journalistic Czar” who will find himself assassinated “by one or other of the high-souled comrades whose lucubrations you have so despotically suppressed.” Hyndman reports that Kropotkin did not see his point.

19th century writers, too, become far more lively personalities when one hears Hyndman tell of their doings. He recalls seeing Henry James standing in the middle of the road loudly denouncing Émile Zola for “that unholy Frenchman’s degradation of literature.” Until that moment, Hyndman writes, a “I had always looked upon [James] as a man of mild temperance” but he became fixed to the spot, erupting in fury—“he could not spare breath for perambulation while the paroxysm lasted.” Oscar Wilde, Hyndman writes, was regarded by those who first met him as “a cultured and rather supercilious exponent of eccentricity in dress and demeanor,” and “a confirmed self-advertiser and self-idolator, with a tendency towards buffoonery.” But Hyndman concedes that Wilde was “an uncommonly clever man, who adopted these queer manner and sun-flower disguises merely in order to attract attention and to gain a hearing for himself.”

The economist Henry George, for whose single tax theory Hyndman had undisguised contempt, embarrassed Hyndman horribly one day by snarfing down whelks while the two stood together on a street corner. Hyndman says that being himself from “non-whelk-eating-at-the-corner civilization,” he was appalled, and “I never see a whelk stall at a street corner to this day but I feel inclined to bolt off in another direction.” (“It is the very small things of life which cause the greatest annoyance,” he says.) Not everyone may find their interest piqued by stories of a gentleman scandalized by the snail-eating habits of a 19th century political economist, but it must be admitted that a great deal of socialist writing from the time is far drier.

One reason I like Hyndman’s memoirs, in fact, is that for an old leftist he is uncommonly interesting. That sounds insulting, but surely any honest comrade will concede that much of our literature is a slog. Hyndman’s memoirs discuss the creation of surplus value and the exploitation of the proletariat but are also full of stray musings like: “I wonder whether all men have the same personal hatred of sharks I found among the sailors I encountered in Polynesia. With some it amounts to a species of mania.” He has a whole digression about watching George Bernard Shaw eat an egg. Hyndman says he looked on “with concealed and silent horror” as Shaw ate “only the white.” This “albuminous repast of his” shocked Hyndman’s “natural sense of the fitting and the congruous in matters gastronomic.” Hyndman concludes that Shaw would write better plays if he ate the yolks, and perhaps ought to be force-fed the rest of the egg, so that “his strong human sympathies, no longer half-soured by albuminous indigestion, would bring the tears to our eyes and tend them gently as they coursed down our cheeks… lyrics of exquisite form and infinite fancy would literally ripple out of him, while his blank verse and his rhymed couplets would be the joy of all mankind.” I am not sure I have ever read anything more bonkers.

These memoirs are indeed, as the title of Vol. 1 promises, the record of an adventurous life. Hyndman visits America and recounts his peculiar encounters with Mormons and the surprising experience of seeing people in the Old West shooting each other over romantic disputes. Hyndman makes a perceptive critical comment on Abraham Lincoln: “The fact that Lincoln himself was a fine character and represented the best of the Western men only makes his conduct the more conclusive evidence that even the ablest and most honest American statesmen of the time did not appreciate the real economic and social seriousness of [slavery].” He is dismissive of Tocqueville’s famous account of American political life, saying it did “little more than record the progress of political forms and the development of political struggles from the point of view of the pseudo-democracy of the economically dominant class,” and is “only valuable as illustrating a phase of cultured European thought at a particular epoch.” He meets a journalist who warns him of the “inevitable tendency of [the United States] towards aggression and Imperialism” and says that “you will see that as the Republic becomes more wealthy and more powerful she will spread herself out, not only commercially but militarily. The old ideas of non-interference will rapidly fade away and the necessities for new market, combined with a desire to make themselves felt, will influence both rich and poor Americans in their external policy… our vast industrial and agricultural resources will be turned to the purposes of war.” This was eerily prescient.

American politics he finds bizarre: “What is it that makes the Americans, who come in the main of the cool phlegmatic stock of northern Europe, so tremendously excitable at election times?” He recalls an electoral meeting in Indiana where people went absolutely wild:

“I never witnessed anything so sudden in my life. Some campaign reference by a favourite speaker, which I did not in the least understand, started the outbreak, and within sixty seconds the whole of that big audience went stark, staring mad. They cheered, they howled, they waved hats and handkerchiefs; they danced, they jumped on the chairs, they invaded the tables. Old gentlemen, white-haired and of venerable appearance, shouted till perspiration streamed down their faces and they were as hoarse as crows.”

He visits Italy during the years of nationalism, following Garibaldi and Mazzini around as they strive to unify the country. He travels to Australia and is alarmed by all the snakes. (He won’t go hunting in the outback because “I can imagine nothing more terrifying than to indulge as a pastime in walking through short scrub, beset with reptiles as poisonous as cobras on every hand, and expecting each moment to tread on one of them and feel his fangs embedded in your calf.”) More significantly, Hyndman gets into arguments with the rich squatters who have seized huge tracts of land on the continent for themselves. He is disgusted by the way Australia is being carved up by people trying to own as much as possible: “I never could endure the idea that the land of a country should belong to a mere handful of people whose forebears had obtained it either by force or fraud, or who bought it from those who had thus acquired it,” he says, and in Australia he watches that entire unseemly process at its very start. Hyndman is frustrated by the fact that the land thieves whose actions he deplores are personally kind to him, but even in his telling, it is obvious that half the people he met quickly ended up being irritated by him and counting the days until he left Australia.

Hyndman’s memoirs do not entirely consist of the relitigation of decades-old arguments and frivolous asides about whelks. He actually deserves credit for being perceptive on a number of issues that few upper-class Englishmen of his time were. He understood that British rule in India was a monstrous injustice. “I had been brought up in an atmosphere of imperialism, so far as India was concerned,” he admits, but he ultimately saw through British rhetoric about colonialism being in the interest of the colonized. He concluded that the Empire was “wholly in the interest of the conquerors,” and that India is “the classic instance of the ruinous effect of unrestrained capitalism in Colonial affairs.” Hyndman insists that all socialists “should thoroughly understand what has been done, and how baneful the temporary success of a foreign despotism enforced by a set of islanders, whose little starting-point and headquarters lay thousands of miles from their conquered possessions, has been to a population of at least 300,000,000 human beings.”

He reports making himself unpopular among Royal Geographic Society colleagues by dissenting from his countrymen’s admiration of Henry Morton Stanley, condemning Stanley’s murder of Africans and wishing for less British enthusiasm for “filibustering journalistic missionaries in their ruthless destruction of natives of the countries they explore.” His remarks on missionaries in general tend to be scathing:

The sheer impudence of these reverend gentlemen and their subsidisers in England who take back from Jerusalem and London a strange Judæo-Anglican hotch-potch to Indian peoples who had debated all the essentials of their teachings thousands of years ago has always appalled me. The conceit of superstition knows no decency and has no historic sense of the grotesque.

While not free of patronizing “noble savage” sentiment, his attitude to the native people of Fiji during his time in the South Seas is vastly more respectful than that of many of his fellow Europeans, and he thought that their lack of market exchange offered a prefiguration of what future socialist relations could look like:

It is impossible not to feel respect for a people who can attain to such a level of culture under such conditions. Their great ndruas or double canoes, held together only by cocoa-nut twine, yet making no water, and their decks so splendidly carpentered with a flint adze that a fine European plane could not touch them; their admirable and elaborate irrigation and cultivation of their lands, and the just apportionment of the product – all achieved without exchange and with no circulating medium – I look back to, even now, as foreshadowing what humanity will attain to on an infinitely higher level when, the gold fetish finally overthrown, and the exploitation of the many by the few put an end to, mankind will resume control over those vastly greater means of producing wealth by which we of to-day are over-mastered and crushed down. Meanwhile the slum-dwellers of our cities are almost infinitely worse off than the meanest kaisis of a Fiji tribe.

Hyndman notes that those Europeans consider “savage” would never neglect children the way that “the profit-mongering dispensation of the modern bourgeoisie” leads to:

I have never met a set of barbarians who permitted the children of the tribe to be neglected – never. They are regarded as of the highest importance, as being those who have to carry on the work of the whole community in the next generation. No such conceptions of the communal ethic have until lately been accepted by English civilisation. The whole problem is looked at from the individual, or separate family, point of view. It is the duty of parents to secure enough under the competitive arrangements of our day, to snatch enough, that is to say, out of the proletarian scramble for existence, to enable them to feed, clothe, and house adequately the children they beget. If not, so much the worse for the children! They must suffer for the sins – or social disadvantages, which mean in practice the same thing – of their fathers and mothers, who should have kept their sexual desires ungratified or the children from being brought into the world. And yet the very same people who talk and write in this way are the first to cry out against any falling-off in the increase of population, and to rush to support schemes of charity for arresting the spread of tuberculosis and other poverty-engendered diseases. That it would be infinitely more to the advantage of the community, and would help even to maintain our army in a higher state of efficiency, to prevent the coming in of such maladies by reasonable attention to the children in their early years, through collective attention and support, is an idea which has only just begun to make way among the highly-educated classes, so blighted has their intellectual development been by a false semi-theological view of the duty of society to its members. To myself who have watched the deplorable physical decay of millions of our population for nearly two full generations, owing to the lack of any rational conception of what ought to be done, the whole thing seems perhaps the most astounding case of social and political imbecility the world has ever beheld. Even the working class of Great Britain has scarcely understood, up to to-day, the importance on every ground of our claim that, if only as a matter of economy, children should be fed and clothed free, in order to enable them to take advantage of the free teaching now at their disposal.

It is sad to realize that, over 100 years later, this act of “social and political imbecility” is still not recognized for what it is, and that simple idea—that it’s in society’s interest to ensure children are well taken care of—is still not yet universally accepted.

Hyndman’s hatred of exploitation and poverty was sincere. He is disgusted by figures like Andrew Carnegie, who “turned loose the Pinkerton “Thugs,” armed with Winchester rifles, to shoot down the workmen out of whose unpaid labour he had piled up his colossal fortune.” His summary of the aspirations that have driven him shows that he understood and believed in a clear socialist vision:

All of us preached, then as now, that no great or permanent benefit could accrue to mankind at large until the payment of wages by one class to another class is finally put an end to and the means of making and distributing wealth are owned and controlled by the whole community. This meant, of course, a complete social transformation, the destruction of the money fetish and the apportionment of wealth – then easily made as plentiful as water – among the whole community, who would all from youth up share in the light, general, useful work and participate fully in the delight of life thus rendered easy of attainment for everybody.

During his time in Italy, Hyndman visits a military hospital, sees the horrifying reality of what war does to human bodies, and develops a distaste for the glorification of military victory:

Ever since, when I have heard or read about splendid feats of heroism in warfare, as during the Russo-Turkish, the Franco-German, and the Russo-Japanese campaigns, I have thought of that churchful of shattered human creatures at Storo, with typhoid fever standing grimly by to reap its harvest of death from those who were recovering from their injuries, and I have felt what a preposterous state of civilisation is that in which intelligent human beings can find no better way of settling their differences than that which I had witnessed.

Still, this did not stop him from supporting one of the most “preposterous” military calamities in the history of civilization, World War I. Hyndman’s views are idiosyncratic and often impossible to defend; he has a section on why workers shouldn’t strike, arguing that it is counterproductive. Many of his beliefs were actively repulsive. His anti-Semitism, sadly common among prominent radicals of the day, makes it challenging to try to redeem any aspect of his work. He speaks in defense of capital punishment, arguing that there is no reason to keep murderers alive. His excuse for supporting military conflict with Germany—that as a socialist he was against nationalism, and the Germans were nationalists—is feeble.

He supported universal suffrage, but the suffragette movement mystified and discomforted him. “I have indeed wondered what induced these ladies to exchange their comfortable homes and enjoyable and useful lives in them for unpleasant and even almost torturing immurement—for Holloway Gaol is a filthy hole infested with vermin—in a worthy specimen of a bourgeois prison-house.” Hyndman confesses that “I know very well I would not run half a risk of such punishment in order to get votes for the two or three millions of my fellow-males still unenfranchised.” Still, he has positive, if patronizing, things to say about Sylvia Pankhurst, who was “active, well-read, pleasant, and very good-looking,” and did “an immense amount of good and useful work” for the socialist movement. Pankhurst’s recollections of Hyndman are less fond. In her memoir The Suffragette Movement she writes that in the early days of the socialist movement when it was “so impecunious that its meetings were generally held in the meanest of mean streets in miserable premises, and frequently over foul-smelling stables,” Hyndman launched a “fierce tirade” against her, saying that “Women should to have influence as they have in France instead of trying to get votes.” Pankhurst portrays Hyndman as a ridiculous figure, one of the only socialists in a top hat, who looked like an “old-fashioned china mantelpiece ornament” with a head too big for his body. Pankhurst’s account may furnish some clue as to why Hyndman’s Social Democratic Federation was destined to remain marginal.

Hyndman is grumpier in recalling his encounter with Sylvia’s sister Christabel Pankhurst, who at age 18 came up to him after a speech and chastised him (“assailed me with the utmost virulence”) for using the term “man” to refer to both sexes. His recollection of the encounter reveals an ugly sexism:

I could not believe at first, seeing that we had always had Universal Adult Suffrage on our programme, and that Herbert Burrows and other Socialists had vigorously asserted, and, if anything, over-asserted, the claims of women, that the young lady, as charming in appearance as she was vehement in her discourse, was in earnest in her stalwart objurgations. But she speedily made it apparent to me that she was. Then, I am bound to say, I began to laugh. This made matters worse still, and she took up her parable against me with a whole-souled prophetic indignation which, for the life of me, I could not regard except from the ridiculous side. It was all sex. I was like unto the rest of that section of the human race to which, owing to accident of birth, I belonged, and it was my object, as I showed by my use of the word “manhood,” to keep women in permanent subjection. It has not been my experience of life that women, whatever may be their general social disabilities as a sex, are very easy to put upon or subjugate as individuals. I told the fair Miss Christabel this, and even went so far as to hint to the young lady that this attack of hers was a not unfair example of the truth as manifested unto me in the past, and I still laughed. I offered at last to shake hands with her, but she would not.

Good for young Christabel. Hyndman might not have been quite so repugnant as Belfort Bax, another prominent early British Marxist who was also a prominent “men’s rights” activist and open misogynist. But when he mentions the suffragettes, he frequently sounds like a type of leftist we may recognize in our own time, who laments the distraction that “identity politics” are causing and wishes to refocus us on the class struggle. (Also like that leftist, however, he has one good point to make: Hyndman argues that many well-to-do suffragettes, in pushing primarily for an equality of formal political rights, had insufficient interest in “the economic and social disabilities to which alike the majority of women, the working wage-earners, and the minority of women, those of so-called loose life, are subjected.”) At least his meeting with Susan B. Anthony produced a positive impression:

“The popular impression about her was quite erroneous, as it nearly always is in the case of men or women who adopt and push to the front an extreme programme. Of course she had raised her voice fairly loud, or she never could have been heard at all in the controversies of the time. But there was nothing about her of the shrill virago or infuriated petroleuse. At the time I met her towards the close of her life I found her a charming, dignified, and highly cultured lady with fine grey hair, lively intelligent eyes, a venerable and imposing face, and a delightful smile—the sort of person who would do credit to any movement.”

Anthony did not live to see Hyndman’s memoir released, but surely would have been grateful to have been judged “not an infuriated petroleuse.”

Vladimir Lenin concluded that “Hyndman’s autobiography is the life story of a British bourgeois philistine who, being the pick of his class, finally makes his way to socialism, but never completely throws off bourgeois traditions, bourgeois views and prejudices.” He wasn’t wrong. Hyndman was described as someone who “seemed to have been born into a frock-coat and top hat” and the fact that he is so obviously not working-class makes for comical moments in his “socialist” memoir. At one point, he laments that the New University Club (for Oxbridge graduates) terminated his membership after he’d given a speech “in favour of the unemployed.” Having previously given up his membership in the prestigious Garrick Club, “expenses in connection with the Socialist movement having become so considerable as not to permit of my belonging to two clubs, I found myself clubless in London, which at first was a curious sensation for me.” What is a gentleman to do when he finds himself clubless in London? Elsewhere Hyndman admits that he still finds himself emotionally stirred by experiences that those outside his social circle might find difficult to empathize with: “I feel at this moment, fifty years later, my not playing for Cambridge against Oxford in the University Cricket Match as a far more unpleasant and depressing experience than infinitely more important failures have been to me since,” he says, which led at least one critic to theorize that Hyndman “had adopted Socialism out of spite against the world because he was not included in the Cambridge eleven to play Oxford at Lords.” (Hyndman can be highly reminiscent of the P.G. Wodehouse’s “Psmith,” a wealthy socialist dandy, and some think Hyndman might have inspired the character.) But while Hyndman is monumentally insufferable and often quite wrong, reading along as he blunders his way through 19th century leftist history can be richly amusing.

There are also some passages in his work here and there that are profound, useful, resonant, or moving. He knows that socialist activism is not all a big jolly jape: “Taking the side of the weak is a very fine thing to read about in a novel, or to see played as a part on the stage, but in actual life it is a very serious and dangerous thing indeed to do.”

Hyndman recounts the seeming futility of trying to spread the socialist message during the early years of the movement.1 “Did you ever speak from an orange-box, which you had borrowed yourself from the old fruitwoman at the corner, to hundreds of dockers at the Dock Gates at five o’clock in the morning, day after day for weeks? I presume not.” But he did, going off and “preaching Socialism and the need for solid combination among all classes of workers as the sole remedy for the hideous state of things which existed; whereby, owing to the excess of casual labour, men were competing and even fighting with one another for a starvation wage on the chance of receiving pitiful daily pay – being treated worse than dogs by the dock companies and their overseers.” Hyndman recounts step-by-step what it was like engaging in political oratory during those days at the docks:

- Acquisition of orange-box for platform, done, in the first instance, in a sheepish, shamefaced way.

- Placing of the orange-box at a convenient corner – still with much diffidence; men lounging around, now the Dock Gates were shut, with their hands in their pockets, and looking on, as I thought, contemptuously, at my proceedings.

- Mounting of the orange-box by the orator, and the commencement of his speech to no one in particular, with the familiar “Friends and Fellow-Citizens.” How cold and empty I did feel, to be sure, and no one near.

- Gradually drifting me-wards of a few of the sad-looking stragglers on slump. Steady increase of numbers as address went on.

- Some interest awakened, and even a little applause from hands reluctantly drawn from pockets gave the speaker courage; he was able to reflect upon the class of men he was addressing. They looked what they were, workers capable of much better things than casual labour, but worn, weary, and anxious, with that unfinished appearance about the neck which the absence of a collar always gives to an observer from the west.

- Attempts at jocularity not badly received, earnest adjurations to the men to combine, pointing out that they could, as a whole, gain for one another together what none of them could gain separately. A little enthusiasm here and there in a fairly big crowd.

- Finish up. Sometimes questions. Return not altogether hopeless.

Over a century later, it is easy to imagine exactly what it felt like to stand on that orange-box and try to rouse a listless group of passersby to rise up in support of revolutionary politics.

Hyndman appears to have been a good political speaker, but his encounters with the actual working class suggest that he better served his movement as a polemicist and journalist. He quotes a wonderful little fable from the socialist weekly newspaper he helped found, Justice, called “The Monkeys and the Nuts”:

A Colony of monkeys, having gathered a store of nuts for the winter, begged their Wise Ones to distribute them. The Wise Ones reserved a good half for themselves, and distributed the remainder amongst the rest of the community, giving to some twenty nuts, to others ten, to others five, and to a considerable number none. Now, When those to whom twenty had been given complained that the Wise Ones had kept so many for themselves the Wise Ones answered, “Peace, foolish ones, are ye not much better off than those who have ten?” And they were pacified. And to those who objected, having only ten, they said, “Be satisfied, are there not many who have but five?” and they kept silence. And they answered those who had five, saying, “Nay, but see ye not the number who have none?” Now when these last made complaint of the unjust division and demanded a share, the Wise Ones stepped forward and exclaimed to those who had twenty, and ten, and five, “Behold the wickedness of these monkeys. Because they have no nuts they are dissatisfied, and would fain rob you of those which are yours!” And they all fell on the portionless monkeys and beat them sorely. Moral. The selfishness of the moderately well-to-do blinds them to the rapacity of the rich.

Some of the questions that Hyndman asks are still being asked today. For instance:

Why is it, by the way, that Liberals are so strongly addicted to “terminological inexactitudes” in politics? Why is it that their special party creed renders it incumbent upon them to play tricks with the truth whenever it suits their purpose? How does it come about that no sane man would think of placing the slightest reliance upon the Liberal Party carrying out when in office the pledges made at the polls in order to obtain a majority?

He is outraged by those who say that “Socialists are necessarily ignorant folk… actuated only by envy,” and when the Home Secretary says that “nobody joins the Socialist movement except for what he can get out of it,” Hyndman writes to demand an apology and laments that he cannot duel the man. (“Duelling has its drawbacks, I am well aware, but it has a tendency to check unseemly misrepresentation on the part of people who are inclined by nature to calumniate, and who allow free course to their malignity when they feel that they are safeguarded from all danger.”)

One passage in the book offers a vital caution for leftists of all times. Hyndman recounts a meeting with one Lady Dorothy Nevill, a Conservative who warned him that all of his rabble-rousing on behalf of the workers was useless. He says that she delivered the following monologue, or something like it, which previewed the strategy of many an elite class and the fate of many a radical working-class movement:

“We believe you to be honest in what you are doing, because we have offered you all a man can hope to get in this country, and you have not chosen to take it. But you will never succeed, at any rate in your own lifetime. We [the bourgeoisie] have had an excellent innings, I don’t deny that for a moment: an excellent innings, and the turn of the people will come some day. I see that quite as clearly as you do. But not yet, not yet. You will educate some of the working class, that is all you can hope to do for them. And when you have educated them we shall buy them, or, if we don’t, the Liberals will, and that will be just the same for you. Besides, we shall never offer any obstinate or bitter resistance to what is asked for. When your agitation becomes really serious we shall give way a little, and grant something of no great importance, but sufficient to satisfy the majority for the time being. Our object is to avoid any direct conflict in order to gain time. This concession will gain, let us say, ten years: it won’t be less. Then at the expiration of that period you will have worked up probably another threatening demonstration on the part of the masses against what you call the class monopoly of the means and instruments of production. We shall meet you in quite an equitable and friendly spirit and again surrender a point from which we all along meant to retire, but which we have defended with so much vigour that our resistance has seemed to be quite genuine, and our surrender has for your friends all the appearance of triumph. Yet another ten years are thus put behind us, and once more you start afresh with, whatever you may expect to-day, a somewhat disheartened and disintegrated array. Once more we meet you with the same tactics of partial surrender and pleasing procrastination. But now, remember, thirty years have passed and you have another generation to deal with, to stir up, and educate, whilst, if I may venture to say so, you yourself will not be so young nor perhaps quite so hopeful as you are to-day. Not yet, Mr. Hyndman, your great changes will not come yet, and in the meanwhile you will be engaged on a very thankless task indeed. Far better throw in your lot with men whom you know and like, and do your best to serve the people whom you wish to benefit from the top instead of from the bottom.”

Hyndman comments that “a quarter of a century has passed since this utterance, and it seems to me the aristocracy, to say nothing of the capitalists, have given way considerably less than Lady Dorothy herself believed they were prepared to surrender.” The more things change, the more they stay the same.

The Record of An Adventurous Life and Further Reminiscences are not widely read today, and I suspect they will never be. Hyndman’s reputation is not going to experience a revival, and it shouldn’t, as he was often ludicrously wrong and pig-headed (H.G. Wells praised his “magnificent obstinancy”), and at his worst was outright bigoted. In parts, his books might as well be titled All Of The Places I Went, The Arguments I Had In Them, and The People I Annoyed. But these memoirs are also a storehouse of historical curiosities, and preserve people and events that should not be forgotten. The 19th century was fascinating and is worth studying closely. The past seems to be disappearing faster and faster these days, and I was pleased to learn about interesting people like Jessie Craigen, Walter Crane, Joseph Arch, Tim Healy, Ettore Ciccotti, Bronterre O’Brien, Marcus Clarke, and to be told about the London Dock Strike of 1889 and West End Riots. Hyndman offers a beautiful tribute to the socialist aristocrat Lady Warwick, who hosted social democratic gatherings on the sumptuous grounds of her estate. It was, he says, her “enjoyment of life and unwearying appreciation of all that is most exciting and delightful and exhilarating in the world [that] render her the more intolerant of a social system in which—though the power to produce wealth is so great that it becomes under existing conditions a direct cause of crisis and poverty—there is no hope that the mass of the actual producers will ever obtain any considerable share of it.” Certain historical facts become distorted over time, and it is useful to be reminded of the truth—for instance, Hyndman reminds us that John Stuart Mill, often presented as a libertarian, accepted the basic tenets of socialism by the end of his life. Reading these books can also remind one of just how similar human beings are across many centuries. The arguments being had then are the arguments being had now, the flaws in people then are their flaws now.

Hyndman also saw himself as being at the beginning of a struggle that would last across generations, and saw that leftist politics are an important way to make sure you do something valuable during the brief time you are alive on Earth. He recalls seeing Eleanor Marx speak one night of “the eternal life gained by those who fought and fell in the great cause of the uplifting of humanity.” That eternal life consists in the “material and intellectual improvement of countless generations of mankind.” Eleanor Marx was one of those who had left Hyndman’s organization in the ugly schism, but he recalls of this particular meeting, “it was a bitter, snow-swept night in the street outside, but in the Hall the warmth of comradeship exceeded that of any Commune celebration I have ever attended. We were one that night.” Unfortunately, the day after, “the antagonism recommenced.” (I recall similar feelings when I attended the 2019 DSA convention. Again, the more things change.)

At the end of his life, Hyndman was disappointed by how little the socialists had managed to accomplish in Britain. In 1881, he had given a talk on “Practical Remedies for Pressing Needs,” advocating “the Feeding of Children in the Board Schools; the Organisation Co-operatively of Unemployed Labour; the Eight Hour Law; the Nationalisation of Railways and Mines; and the Construction and Maintenance of wholesome Homes for the People by public bodies, national and municipal, at public cost.” When he wrote his memoirs, he said it was “sad to recognize, after twenty-nine years of assiduous agitations, that not one of these remedial measures has yet been passed into law, and that the physical, mental and moral degeneration of large masses of our population, which they were specially intended to check, has gone steadily on ever since,” and “the capitalist class and their hangers-on in this country will not accept admittedly beneficial palliatives of their anarchical system.” 100 years later, the progress made both in Britain and elsewhere is still disappointing. But in his preface, Hyndman writes beautifully of why he can still find peace:

“So when we, the small men of our time, pass unregarded to the rest of the tomb, this only consolation shall close our eyelids in their never-ending sleep: that though our names may be forgotten our memory will ever be green in the work that we have done and the eternal justice we have striven for.”

Everyone dies, often sooner than they expect. Hyndman, having founded the British Marxist movement, died and was almost entirely forgotten. But as he says, while those like him may be small and unregarded, they can take consolation that they did some small part in working toward justice. We should feel the same in our time. Political action is a way of making your life count, and makes it easier to accept your mortality, knowing that you have contributed something, however small, that will last beyond your lifetime. Hyndman, flawed, possibly beyond redemption, nevertheless helped begin a valuable project that is being worked on to this day. Let us each strive to make our own contribution during the time we have here.

Hyndman relates a wonderful anecdote about his wife endeavoring at length to convert a worker to the socialist cause, thinking she had succeeded, and then being dashed with a few simple words. It is given its power by its length, so I quote it here in a footnote: “I remember on one occasion my wife, who is a countrywoman by birth, trying her propagandist powers, which are really very good, upon an agricultural labourer. She held forth to him upon his miserable wages, his tumbledown and cramped cottage, his lack of opportunities of enjoyment, the manner in which the common land hard by had been filched from him, the shameful fact that he could not get a nice bit of garden ground at anything at all within hail of the yearly rent paid by the farmers for their acres, the way in which all the old perquisites and easements had been taken away, the long winter in which, now that thrashing was performed by machinery and there was little arable land around, there was little to do and therefore little to get. The man listened attentively and seemed to agree with her, so my wife felt encouraged. She went on to point out that all this trouble arose from the fact that he had no property; that he owned nothing, not even the cottage he lived in or the agricultural implements he used; that he was bound to take low wages, because if he did not there was no other way by which he could live himself or get food for his wife and children; that there was no union between him and the other men so that they could make common cause against the farmer and the landlord; that the reason why he had to pay so much rent for his cottage was that cottages in the neighbourhood had been pulled down by the landowners in order to reduce rates on their estates years ago; that owing to cheap food and cheap hay and cheap fruit coming in from abroad by low rates of railway freight, things were getting worse, and were likely to be worse still. The countryman listened on, told how he remembered when he could do better than he could today, and grumbled bitterly at his lot. He had a wife and children: what would become of them?—he was asked. The “ House” was not a comfortable habitation either for the young or for the old. The good man agreed. He even averred it was a great shame honest folk should be so put upon—that it was. My wife thought she had got a convert. So she told him what a good garden at a light rent, co-operation in sending his produce to market, joint ownership of the land by himself and his kinsfolk in the towns, would do for him; how he could help them and they him to have all that was needed, with no anxiety at all about the future; how his children would be much better off still when this great change had been brought about. There he sat listening stolidly, with the land about him, which I myself remembered as well-tilled and prosperous, going steadily out of cultivation, and the active village of the last century becoming a deserted Sleepy Hollow of today. When my wife had quite finished – and it took a long time to put all this after a fashion to be understanded of the Sussex mind – he took his clay pipe slowly out of his mouth, and spat and spoke. ‘Thank you, marm. You thinks so! I thinks otherwise.’” And that was that. ↩