Melt the Crown

How the myth of the genius director has erased the careers of some very talented women, and why it’s time for the “auteur” to be tossed out entirely.

I have seen every young, supple, French New Wave ass in existence. Brigitte Bardot’s in Le Mepris. Catherine Deneuve’s in Belle du Jour. My “Intermediate Film” class in college should’ve been named “A Case for the Male Gaze,” given my professor’s predilection for young French women. After screenings, the lights would flicker on and he’d swivel around in his chair, his wiry eyebrows raised suggestively, as if to say, did you see that? And yes, we saw that—again and again. Given his taste for blondes, I’m surprised he never made us watch The Last Picture Show. Cybill Shepherd might have been American, and the 1971 film firmly New Hollywood rather than New Wave, but it featured a pliant beauty experiencing a sexual awakening, and therefore should’ve found its way onto our syllabus. But then again, we weren’t shown very many of the “great” American films.

Contrary to most American film programs, at the Rhode Island School of Design there was virtually no mention of Peter Bogdanovich, Francis Ford Coppola, Stanley Kubrick or—god forbid—George Lucas. It wasn’t until I picked up Peter Biskind’s book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls during my junior year that I became familiar with the New Hollywood movement and the drug-addled, sex-crazed cinephiles who revolutionized American filmmaking. Like the French New Wave before them, these men seized creative control from an outmoded studio system—where the producer was king—and fixed the newly minted crown of auteur onto their own heads.

Auteur theory, popularized by French New Wave director François Truffaut, placed the director in the role of the single most important person on a film set. American directors—many of whom were wildly insecure and favored the shadows of dark cinema houses—loved the new doctrine. In this framework, they weren’t small men eclipsed by the glowing, colossal images on the silver screen; they were stars in their own right. It certainly seemed liberating, even righteous, to challenge the money-grubbing studio system, which had dominated Hollywood from the 1920s up until the late 1960s. The men with the money were now—in theory—secondary to the artists with the vision.

At least, that’s how auteur theory is usually framed, as a revolutionary crusade against “the man.” In practice, it’s anything but subversive. It’s just a truer embrace of “the man.”

When auteur theory debuted in the pages of the radical film journal, Cahiers du Cinéma, it was considered quite provocative. The theory torched France’s prevailing “Cinema of Quality” trend, in which directors faithfully—and artlessly—adapted scripts to screen. In contrast, the director-as-auteur would be someone who challenged the form with a distinctive vision and style, which the young Cahiers critics—Jean-Luc Godard, Eric Rohmer, François Truffaut—later exemplified as pioneers of the French New Wave. But these men, obsessed with the idea of personal genius, also held that the director was the sole author of a film. They developed a cult of personality around directors they admired, sometimes overlooking the director’s lesser work in favor of his larger oeuvre. Essentially, they set the stage for what Kate Muir identified in The Guardian as the Scorsese-Tarkovsky-Fellini triangle, or worse—the Tarantino devotee.

Godard and Truffaut may have been communists—the pair shut down the 1968 Cannes Film Festival in solidarity with Parisian student protests—but they were surprisingly conservative when it came to authorship. They would indeed wrestle with this discrepancy later in their careers, but the New Hollywood directors that idolized them never did. McCarthyism and the blacklist had decimated the Hollywood left only a generation before, which meant that the French insurgent spirit got lost in translation. But the fanatical adoration of the auteur and his singular talent translated—and endured—just fine.

Proponents of auteur theory would have you forget that filmmaking is, by definition, a collective art. A painter can recede into his tiny studio, or a writer to her desk, but a filmmaker relies on a vast network of collaborators to realize their vision. Ask any filmworker today and they’ll nod enthusiastically, yes, of course, we’re all important players. But implicitly they know that the collective has been co-opted in the service of one person: the director. That person, to this day, is a man about 84 percent of the time, according to The Celluloid Ceiling (an organization that has been amassing data on behind-the-scenes employment of women for the last twenty-two years.)

Another dent in the auteur crown is that many of the most famous directors—the type that cinephiles tend to regard as gods among men—had brilliant wives who not only raised their children while they seduced young starlets, but shaped their stories, pitched career-defining ideas, and saved ill-fated projects. Despite the extraordinary contributions of these women, their debut appearances at the height of second wave feminism, and their (limited) number of awards, they’ve largely been erased from film history. If they’re mentioned at all, it’s usually as the wives of famous auteurs, not as collaborators or creatives in their own right. But when you learn about women like Polly Platt or Marcia Lucas, it becomes clear: auteur theory is just that—a theory. And one that we should have tossed long ago.

I just saw a movie that sucks, but the guy who made it knows how to make movies. Get him in here. – Bob Rafelson; 1970s director, producer, and philanderer

The above quote would never be said about a woman. Not in 2021, and certainly not in 1968, when film producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider wanted to work with Peter Bogdanovich. The twenty-eight year old Bogdanovich—better known to the Sopranos-binging generation as Doctor Melfi’s therapist—had just released his first feature film, Targets. The movie may have “sucked,” according to Rafelson, but it secured Bogdanovich a meeting with the producers who made the independent sleeper hit Easy Rider. When Bogdanovich and Schneider met to discuss a potential collaboration, it was a standard dinner with the wives—except that Polly Platt was one of the wives.

Schneider quickly dismissed the first idea that Bogdanovich pitched. “Somethin’ else,” he shrugged, a dreaded phrase for any filmmaker. Most of us would have come prepared with a few pitches, but the aspiring auteur drew a blank. “There’s Larry McMurtry’s The Last Picture Show,” Bogdanovich’s wife Polly offered. She described the novel for Schneider (the son of the head of Columbia Pictures, incidentally) and he liked it. Of course, he reportedly expressed his interest by turning away from the woman pitching the film and toward her dejected husband. Bogdanovich—a Manhattan-bred film brat—didn’t find the small town Texas story appealing and, unlike his wife, hadn’t read the book. When Schneider asked Bogdanovich to send him a copy of the book, the director sulkily told him to buy a copy himself.

Despite this shocking display of arrogance, Bert Schneider picked up the film, under the condition that Bogdanovich “write some nudity into it.” Likened to Orson Welles’ seminal work Citizen Kane, the 1971 film version of The Last Picture Show racked up eight Academy Award nominations, securing its director, Peter Bogdanovich, a place in the New Hollywood movement. Bogdanovich—who once shamelessly worried his name would be too long to fit on a marquee—became a household name. Further solidifying his auteur image was the 20-year-old beauty he had on his arm, Cybill Shepherd, the star of The Last Picture Show…and the woman he’d abandoned his lactating wife for. Bogdanovich had an affair with his lead actress just months after Platt had given birth to their second daughter.

It’s a familiar story—the director falling for his star—but few are as outrageous as The Last Picture Show. Because in addition to pitching the project that made her husband famous, Platt designed and built the sets, made the costumes, and did hair and makeup for the entire cast. And that’s just what she did on her own. The collaboration between Peter and Polly was so apparent that even Shepherd couldn’t help but remark to Platt:

People say you direct because he sits with you and you draw something on the script. You tell him what the shots will be.

Shepherd wasn’t the only one who noticed Platt’s influence either. Platt described her co-working relationship with her husband as, “he’s the locomotive and I’m the tracks.” The couple’s closest friends and colleagues even lamented how Bogdanovich’s films suffered after their eventual divorce. The only person who didn’t see how instrumental Polly was to Peter’s films was Peter himself. In the middle of production—and his very public affair with Shepherd—Bogdanovich asked Platt why she didn’t just “go home.” The man consulted his wife on a daily basis but still thought she was redundant. Confident that the film would be a success and that she was just as much the “author” of the film as her husband, Platt stuck with it. The sole credit that Platt received for The Last Picture Show? Production Designer. Which, while an esteemed and elusive credit for women at the time, was an erasure of the depth and scope of her overall work.

It’s this kind of omission that aids the myth of the auteur. The Academy nominated Peter Bogdanovich for Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay. The papers praised Bogdanovich—and Bogdanovich alone—for his vision. And why wouldn’t they? It was his name that appeared in the credits.

Despite her personal anguish over her husband’s affair and their subsequent divorce in 1971, Platt still believed in their creative partnership. She went on, post-divorce, to make two more hits with Bogdanovich: What’s Up Doc? and Paper Moon. But it wasn’t until Platt creatively split from Bogdanovich that her career really took off—and his fizzled out. She produced several films and fostered the careers of JJ Abrams, Cameron Crowe, Wes Anderson, and Matt Groening. You might have only just learned about Polly Platt, but you know at least a few of these men—and Platt was instrumental in making them happen. Naturally, this is the part of her career that has largely been forgotten, eclipsed by the salacious affair surrounding The Last Picture Show.

It wasn’t until The Invisible Woman premiered last year—the latest installment of Karina Longworth’s podcast You Must Remember This—that the extent of Platt’s influence really gained much in the way of public recognition. Because although she’d had successes, Platt had also been the “uncredited producer, unofficial writer and talent whisperer” on several films. From Terms of Endearment to Say Anything, Platt did far more than her credits suggested. But we wouldn’t know any of it if Longworth hadn’t unearthed Platt’s unpublished memoir, which she wrote before she tragically died of ALS in 2011.

As Longworth notes, it wasn’t Platt’s death that prevented her from publishing her autobiography—it was Platt’s fear that it was “too gossipy.” Which is painfully ironic, given that Easy Riders, Raging Bulls—the 1998 tell-all by Peter Biskind that I stumbled on during my junior year—is widely celebrated for its uninhibited look at the era Platt experienced firsthand. That is, celebrated by most people. Peter Bogdanovich was incensed by Biskind’s book, saying, “I spent seven hours with that guy over a period of days, and he got it all wrong.” Robert Altman said that he wished Biskind dead. But it’s a 2013 quote from William Friedkin, the unhinged, womanizing director of The Exorcist, that’s most telling:

I’ve actually never read the book, but I’ve talked to some of my friends who are portrayed in it, and we all share the opinion that it is partial truth, partial myth and partial out-and-out lies by mostly rejected girlfriends and wives.

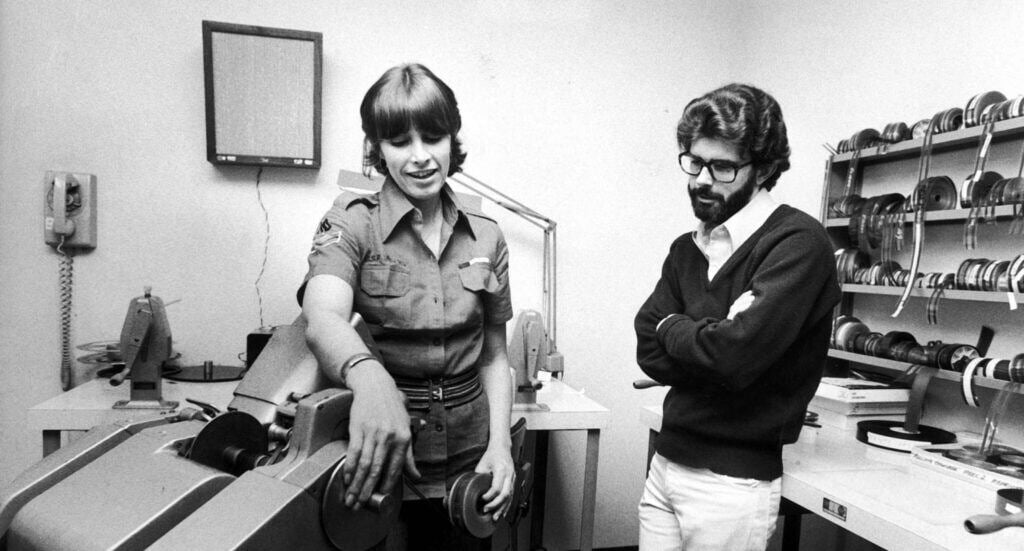

Biskind did what most film critics/historians of the time wouldn’t: he actually talked to the “rejected girlfriends and wives.” It seems like an obvious oversight now, but these women had been deemed so inconsequential that no one had bothered to talk to them before. If their husbands were the individual geniuses, revolutionizing the industry, what was the point of talking to the lucky gals who just hitched a ride? At best, they were homemakers and mothers. At worst, they were opportunistic freeloaders. Certainly, they were never, ever seen as collaborators. This is the delusion that Biskind broke with his book, to the dismay of many famous directors, including George Lucas, whose wife—the gifted editor Marcia Lucas—was also one of Biskind’s subjects.

In the early days of film, editing wasn’t considered an art. The work was dismissed as menial, tedious and not unlike sewing, with all of its threading and cutting. Naturally it was working-class women, and their so-called “nimble-fingers,” that cut the very first films. These women laid the foundation for editing as we know it today, but were routinely omitted from film credits and press write-ups because of their lowly status. But while the craft was downplayed, there were rare glimpses of acknowledgement, as in a 1925 Motion Picture Magazine article by Florence Osborne:

Among the greatest ‘cutters’ and film editors are women. They are quick and resourceful. They are also ingenious in their work and usually have a strong sense of what the public wants to see. They can sit in a stuffy cutting-room and see themselves looking at the picture before an audience.

Fifty years later, it was this exact skill that made Marcia Lucas an exceptional editor. “I like to become emotionally involved in a movie. I want to be scared, I want to cry…” she said, speaking to Biskind in 1998. Before the preview of Star Wars episode IV—the second film that Marcia cut for her husband George—she said, “if the audience doesn’t cheer when Han Solo comes in at the last second in the Millennium Falcon…the picture doesn’t work.”

Her keen instinct for editing was praised by directors like John Milius and Martin Scorsese, the latter of whom she cut several films for, including Taxi Driver and Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. But, as with Polly Platt, the famous auteur husband didn’t fully recognize his wife’s talent. When George’s first feature film, THX 1138, was panned by the studio (as Marcia had anticipated) George was less than humbled. Marcia told Biskind:

I never cared for THX because it left me cold. When the studio didn’t like the film, I wasn’t surprised. But George just said to me, I was stupid and knew nothing. Because I was just a Valley Girl. He was the intellectual.

George didn’t stop belittling his wife once he became successful. When referring to scenes that Marcia cut on Return of the Jedi years later, he said she edited all of the “crying and dying scenes.” Lucas didn’t think much of creating emotionally resonant work, famously claiming, “emotionally involving the audience is easy. Anybody can do it blindfolded, get a little kitten and have some guy wring its neck.” Marcia’s ability to find the emotional crux of a scene was a strength, but George essentially skewed it as a weakness of feminine sentimentality. And yet, the enduring power of the original Star Wars series is largely due to Marcia’s influence.

And it wasn’t just Marcia: everything about Star Wars was a genuine team effort. George Lucas was mortified by the first rough cut of A New Hope. He thought the original editor, John Jympson, was making the film too campy. He fired Jympson and replaced him with Marcia, whom he entrusted with one of the most challenging and impactful scenes: the Death Star trench run. As Michael Kaminski notes in his essay, In Tribute to Marcia Lucas, Marcia had to rebuild the scene from the ground up. The scene as scripted was anticlimactic and lacked tension—George himself lamented that he wasn’t a strong writer. Given the time crunch, Lucas also had to bring on two more editors, Richard Chew and Paul Hirsch. A New Hope was a collaborative effort, particularly in the final days of the rough cut. As Hirsch described in J.W. Rinzler’s The Making of Star Wars:

We put it all together and spent about three or four days as a tag team. George, Richard, Marcia and I would sit at the machine each for a couple of hours, taking turns and making suggestions.

Marcia won an Oscar for her editing of the film, alongside Chew and Hirsch. She didn’t speak at all at the acceptance, but the award itself meant recognition, which would prove to be important when her contributions were later downplayed. According to Kaminski, Marcia was “practically erased from the history books at Lucasfilm.” So-called definitive documentaries and books about Star Wars generally cite Richard Chew as the primary editor, or exclude Marcia altogether. While she was credited for cutting Episodes IV and VI, she is still uncredited for contributions made to The Empire Strikes Back.

And that’s just her uncredited editorial work. Marcia was with George while he was drafting the early scripts for Star Wars and made countless suggestions: it was her idea to have Obi Wan die and serve as Luke Skywalker’s spirit guide. The couple divorced in 1983, and after Marcia left, Lucas’ work became notably self-indulgent, shackled to an increasingly soulless franchise. Mark Hamill himself noted that “there was a huge difference in the films…[Lucas] did when he was married.” It’s not a mystery as to why. While others fawned, Marcia dared to tell her husband when something didn’t work. According to Marcia:

I think he resented my criticisms, felt that all I ever did was put him down. In his mind, I always stayed the stupid Valley girl. He never felt I had any talent, he never felt I was very smart and he never gave me much credit. When we were finishing Jedi, George told me he thought I was a pretty good editor. In the sixteen years of our being together I think that was the only time he complimented me.

Much like Polly Platt, Marcia Lucas made her husband’s films better, and they suffered without her. The male resentment she described was common enough among New Hollywood directors: Francis Ford Coppola complained that his wife Ellie was “like a regular person” who never made him feel confident. But in a conversation with Biskind, Coppola justified his flagrant affair with his babysitter-turned-assistant Melissa Mathisson by saying that she “was like a girl who [had] a crush on her professor. Her confidence in me made me feel confident.” His wife Ellie Coppola was “regular”; she didn’t feed his outsized, auteur ego, unlike the young, impressionable Mathisson who appeared to see Coppola as he wished to be seen.

George Lucas, Coppola’s protege, seems to have fully bought into auteur theory. As a young filmmaker, he had dreamed of creating an experimental film studio, one that would capture the independent spirit he felt as a film student at UCLA. Like several other New Hollywood directors, Lucas fancied himself a New Wave renegade, and was an admirer of Jean-Luc Godard. According to Marcia, George said that Star Wars was going to be his “last establishment-type” film—it was his cash cow, a stepping stone to autonomy. Instead, he ended up expanding the universe and built the multi-million-dollar facility, Skywalker Ranch. Lucas initially claimed the ranch was for his wife, but the massive undertaking forced Marcia to put her editing career on hold, so that she could act as its interior decorator. Return of the Jedi would be the last film that Marcia ever cut. While it’s not entirely clear why—Marcia reportedly received several offers to edit—Kaminski claims that she was burnt out from supporting George’s empire and his workaholic, obsessive tendencies. Her husband’s condescension over the years couldn’t have helped much either.

One could argue that Marcia Lucas and Polly Platt were fortunate to even have careers that we could uncover. Countless women were (and still are) driven away from the industry. If it hasn’t been an issue of parity, discrimination, or sexual harassment, it’s been the industry’s inhumane, anti-family working hours. They were better off than most, right? Not quite. Their careers were unequivocally stunted by their husbands and a sexist industry that has persisted despite feminist advances.

Bogdanovich and Lucas met their wives while working on productions in lateral positions: Polly was a costume designer on a play Peter was directing, while Marcia and George met as assistant editors on a documentary film. They got married while they were all still young and in pursuit of their dreams. “Talent” doesn’t account for Bogdanovich or Lucas’ career trajectories or Polly and Marcia’s erasure, as their peers held that the directors’ wives were just as talented—if not more so—than their husbands. Harrison Ford famously complained to Lucas of his writing: “you can type this shit, but you sure can’t say it.” According to Biskind, Lucas wasn’t a terribly articulate director either, with his only instructions being, “OK same thing, only better” and “Faster, more intense.”

Polly Platt never got to direct a film, though she always wanted to. As Longworth details, she had a shot at directing the 1987 divorce film War of the Roses, but it was ultimately given to Danny DeVito after clashes with the film’s writer, Michael J. Leeson. As male writers are oft to do with divorce films, Leeson made the husband sympathetic and the wife a bitch (hi, Marriage Story and Kramer v. Kramer). Platt argued that the husband and wife should be equally awful. Leeson’s response? “I don’t give a fuck what you think.”

After fighting tooth and nail to be the first woman inducted into the Art Directors Guild (the organization’s president once referred to her as “Polly Platt, a wife of, Art Director”), Platt gave up her fight to direct a film. She wrote in her unpublished memoir, as shared by Longworth: “One of the reasons…I never became a director was because I never found someone like me who was so wholeheartedly for the director and watching their backs.” This lack of institutional support was and remains common. The industry reluctantly accepted wives but there was a limit: Polly Platt—and Marcia Lucas—would never be handed the type of opportunities that would be readily available to their husbands. They would never be considered auteurs: Platt because she would never direct a film and Lucas because auteur theory doesn’t make room for anyone besides the director.

The erasure of accomplished women like Marcia and Polly keeps the “celluloid ceiling” frustratingly fixed. What’s worse is that generations of women have been deprived of learning their predecessors’ stories, their pitfalls, and the ways in which they persevered. That’s lost time that pushes back benchmarks, leaving us to celebrate meager and incremental progress.

This isn’t a 20th century problem that went the way of mustard-tinted glasses and sideburns either. You’ve heard of Peter Jackson and Christopher Nolan, but you may not have heard of their wives/creative partners, Fran Walsh and Emma Thomas. Unlike their predecessors, you won’t find (uncredited) next to any of their titles on IMDb, but their contributions to franchises like The Lord of the Rings and The Dark Knight aren’t well known. While Walsh is an intensely private person who understandably shies away from the media circus around LOTR, her absence from the discourse adds to the illusion of her husband’s singular genius. Like Platt, Walsh actually pitched the project that put her husband on the map and like Bogdanovich, Jackson didn’t initially want to make it. According to a 2012 New York Times piece, it was Walsh who wanted to make Heavenly Creatures, the 1994 film that introduced actors Kate Winslet and Melanie Lynsky, the latter of whom said that the couple “felt like co-directors” on the film. Walsh and Jackson’s manager took it a step further saying that they, alongside longtime collaborator Philippa Boyens, “are all so involved together in every layer and detail of their productions that sometimes it’s hard to distinguish whose voice you’re hearing in a particular scene or moment. They are perfectly blended.”

In light of all this erasure and lost potential, the natural—and liberal—argument might be that we simply need more female auteurs, more women who get to take all the credit from what is nearly always a collaborative effort. Let’s just have more girlbosses in the director’s chair! My response to this is both no, and absolutely not.

Critique of auteur theory is nothing new. Prescient film critics like André Bazin (who founded the theory!) and Pauline Kael identified its flaws as early as the 1950s, with Bazin warning that its followers could become an “aesthetic personality cult.” Kael also worried that a theory that prioritized personal style would diminish the work, saying in her juicy, 1963 takedown Circles and Squares: “often the works in which we are most aware of the directors personality are his worst films—when he falls back on the devices that he has already done to death.” (Someone please check on Martin Scorsese.)

The rise of #TimesUp and #MeToo has also made us question the validity of the difficult male genius who feels entitled to take liberties with the women around him. But contemporary critiques usually stop short of tossing the theory out, which Kael argued for 58 years ago. Instead, women are indeed encouraged to seize the auteur crown for themselves. Writers like Shelley Farmer fairly ask, Why Aren’t More Female and POC Directors Considered Auteurs? The case is always made that auteur theory is racist and sexist (it is), and that more female directors need to be recognized (they do). We could certainly amass an international list of brilliant women that qualify as auteurs. But my question is: why would we want to?

We can’t retro-fit auteur theory to be feminist; it’s inherently debasing and corrupting. Toxic exceptionalism and ego aren’t man-made glitches of the theory: they’re features. If women assume the ideology of the auteur, treating the collaborative work of filmmaking as a personal fiefdom, then they’re likely to run into the same issues as the men. Girlboss feminism argues that women simply need access to the same opportunities as men, at which point women’s “natural” compassion and collaborative instincts will kick in. But consider the example of Miki Agrawal, the notorious former THINX SHE-eo. Agrawal was lauded as a shero (sorry, last one) for co-founding a company that revolutionized feminine hygiene products and destigmatized menstruation. She also happened to shame female employees for asking for raises (the only employees who successfully negotiated raises were men), sexually harassed several members of her staff, and created the role of “Culture Queen” in lieu of an HR department. YAS.

So no, we don’t need to replace the evil despot with another. We need to melt the crown. But in order to do so, we need to dismantle other barriers and falsehoods that seem foundational to the entertainment industry.

Hollywood is still, despite the supposed work of the great male auteurs, dominated by wealthy studios, producers, and legacy holdouts. The Academy itself was originally created by MGM executive Louis B. Mayer to fend off collective labor. According to Dan Duray, writing in VICE on the origins of the Oscar, Mayer realized that if he doled out enough medals, filmmakers would “kill themselves to produce what [he] wanted.” Mayer might not have stopped the unions (depending on your perspective), but he succeeded in curating films to his liking—and to the liking of the Academy’s mostly male, white membership. The Oscars have always skewed white and male: only this year did Chloé Zhao and Emerald Fennell become the first two women simultaneously nominated for best directing. Zhao also made history as the first Asian American woman to win an Oscar in that category. It’s historic, but that’s mostly because the Academy made it historic by routinely omitting women and people of color in the past.

In the meantime, Eliza Hittman’s film, Never Rarely Sometimes Always, was snubbed entirely. The sensitive, pro-choice film premiered at Sundance and dominated the Independent Spirit Awards, but was notably missing from this year’s nominations. The reason was a bit of a mystery until Hittman shared an unhinged email she received from 80-year-old Oscar voter, Kieth Merrill. He wrote:

I received the screener but as a Christian, the father of 8 children and 39 grandchildren AND pro-life advocate, I have ZERO interest in watching a woman cross state lines so someone can murder her unborn child. 75,000,000 of us recognize abortion for the atrocity it is. There is nothing heroic about a mother working so hard to kill her child. Think about it!

As of 2016, the median age of Oscar voters was 62, with only 14 percent under the age of 50. Only seven women have been nominated for Best Director in the Academy’s 92 year history. The first woman to win was Kathryn Bigelow in 2010 for The Hurt Locker. You know, the vaguely pro-Iraq War film, where Jeremy Renner plays a hot headed but steady-handed bomb technician who’s addicted to war? Where he returns home just to tell his infant son that his true love is the military-industrial complex? I’m sure Merrill and his 39 grandchildren loved The Hurt Locker.

And while Chloé Zhao’s Nomadland is certainly well-directed and visually striking, it’s been criticized for its sunny portrayal of the gig economy. The first thing you see at Francis McDormand’s seasonal Amazon job? A cheery safety lesson followed by a cozy lunch with colleagues––a far cry from the notorious hazards and rushed 15 minute lunches associated with the e-commerce giant. In Variety, Wilfred Chan notes that Zhao wanted to “avoid politics” with her film. This apparently meant omitting that Linda May––a real-life, elderly Amazon worker who appears in the film––was injured on the job. Instead there’s McDormand, who in her own words, loves to work and says of the union-busting company: “it’s great money.”

Interesting, isn’t it, what stories the Academy praises versus what it shames? And isn’t it worth noting what stories are allowed to shape the public imagination and our sense of what is virtuous, what is criminal, and what is possible?

Institutions like the Academy aren’t going to liberate female filmmakers. They’re still squeamish about a woman’s right to choose what to do with her body on film. The Academy will continue to eke out Oscars for women and people of color, slowly, as they’ve done since their inception. Awareness of the problem only goes so far. Overall, women only made up 21 percent of creative roles working on the 100 highest-domestic grossing films in 2020. Of the top 200 films from 2018-2019, people of color only made up 14 percent of directors. The feigned shock and awe when these statistics are released each year is tiring, considering that the numbers haven’t improved much—and in some years have slid—over the last 22 years. Issues of equity are always met with the same, tired refrain: change takes time. There seems to be an unwavering faith that we’re on a linear path towards a more progressive and equitable future. But this couldn’t be further from the truth for female filmmakers—we’ve actually already had a golden age.

Women dominated the early days of film, and not just when it came to editing. From directors to visual effects artists, women occupied a wide variety of roles. It’s worth noting that this period is better documented for white female filmmakers than it is for Black female filmmakers. With the exception of Oscar Micheaux, Black filmmakers are historically overlooked and, as Columbia University’s Women Film Pioneers Project (WFPP) notes, most research has only uncovered the Black men involved in the silent era. But according to Jane Gaines, the organizer of WFPP, women at large “were more powerful in cinema than any other American business—to the point that more women than men owned independent production companies in 1923.” Alice Guy-Blaché, the first documented female filmmaker, started her career as early as 1896. To say she was prolific would be an understatement, as some historians believe she directed, wrote, and produced over a thousand films. Many of them were shorts, but several were at least a half hour long.

This all changed when filmmaking became a lucrative business and Wall Street started investing. What was once hundreds of small, experimental studios became a handful of monoliths helmed by white male executives. As a result, women were systematically purged from the jobs they practically created. Universal didn’t hire a single female director for nearly sixty years, from the mid-1920s to 1982. Of Blaché’s thousand-plus films, only 150 survive.

This loss is harder to swallow when you recognize it was never about time, but about theft.

So at this point, I’ve torn everything apart. I’ve undone the myth of progress. I’ve desecrated auteur theory. I’ve risked being labeled antifeminist for questioning Kathryn Bigelow and Chloé Zhao’s Oscars. How are women supposed to achieve? How do we make the industry more equitable? It would be great if we could harness some of the energy of #OscarsSoWhite and just abolish the Academy. But seeing as that’s not going to happen any time soon—and that it’s hardly the most oppressive part of the system—we have other work to do.

We need to create far more mentorships and clear-cut paths to above-the-line (i.e., creative) positions. I’ve worked as a post-production administrator in scripted television for the last six years. As an editorial worker facilitating conversations between production and post, I’ve worked with many directors. When I’ve asked for advice on how to break in, they’ve said things like, “it’s not very clear-cut” or “shoot videos for a friend’s startup.” I’m a scholarship kid from Brooklyn who graduated from RISD with 40k in student loan debt—I don’t have friends with startups. Not to mention the fact that a decent cinema camera can cost upwards of $8,000––which isn’t easy to meet when you’re an underpaid, non-union worker.

Film festivals—once considered independent havens for little-known filmmakers—are also cost prohibitive. Submissions run anywhere between $25-$75 and you never apply to just one. It’s not likely that they’re going to showcase a film shot on a shoestring budget either. We live in an era when enormous companies like Apple, Netflix, and A24 compete to shell out outrageous amounts of money to buy the rights of “indie” films made by already established directors. Not surprisingly, festivals also have a diversity problem. The Time’s Up Foundation analyzed the top five global festivals—Berlin, Cannes, Sundance, Toronto, Venice—and found that over the last three years, only 25 percent of the directors in competition were women, and of those only eight percent were women of color. I can only imagine what the numbers would look like if they analyzed the economic background of their filmmakers, too.

We also need to reframe the way that filmmaking is taught. It never occurred to me to question the notion of an auteur in college: the concept was presented more as more of a fact than a theory. I wish Noah Hutton’s handbook was around when I was a student. After working on several exploitative sets, Hutton created a freely available filmmaking handbook that centers things like consensus-based decision-making, humility, and humor, which he employed on his latest film, Lapsis. The most refreshing principle? That if you’re tired, heartbroken or sick on set, you go home. According to Hutton, there was “no air given to the myth of the macho, lone-genius filmmaker with everyone else working at their whim.”

(To hear more about this film and filmmaking principles, consider joining our Patreon to listen to an interview with Noah Hutton.)

No one is suggesting that we get rid of the director and have the entire crew deliberate on how to frame a shot. Nor are we saying that we can’t acknowledge the specific contributions of individual directors. We just need to acknowledge that a film is a product of collective labor and as such, should be an equitable and inclusive experience for all.

Personally, I love the work of director Agnes Varda. While I may have only seen one of her films at RISD—her empowered nudes weren’t seductive enough for my professor—she directed a whopping 46 films until her death at the age of 90 in 2019. Until Criterion’s subsequent box set, Varda was the forgotten godmother of the Left Bank, a decidedly less devout offshoot of the French New Wave. From her 1968 documentary on the Black Panthers to her ultra-modern magnum opus—One Sings the Other Doesn’t—her work is radically feminist and endlessly curious. Her voice is distinctive, yet you never get the impression that she’s overly concerned with style. After learning about Marcia Lucas and Polly Platt, it’s worth noting that Varda was also married to renowned filmmaker Jacques Demy. The introductory essay to Varda’s Criterion set describes their marriage as “an unusual heterosexual union for the time.” Demy was bisexual, but that wasn’t what was markedly unusual about their partnership: it was that it was built on mutual support and respect for each others’ work.

If only the women on the other side of the Atlantic were so lucky.