New York: The Invention of an Imaginary City

How nostalgic fantasies about the “authentic” New York City obscure the real-world place.

Chapter 1: “He adored New York City, idolized it all out of proportion.” Uh, no, make that, “He romanticized it, all out of proportion. To him, no matter what the season was, this was still a town that existed in black and white and pulsated to the great tunes of George Gershwin.” Uhhh, start over…

“New York was his town and it always would be.”

—Woody Allen as the writer Isaac Davis, opening monologue, Manhattan

At the beginning of a different story about New York, a nervous young man and the woman who will soon be his wife are standing at a bus station in Montreal. They’re about to start new lives in the strange foreign land of the U.S., and are being seen off by the man’s father. It’s August, and the warm Canadian air moves slightly as the bus finally appears, the words “New York City” displayed in the sign on top. The father turns to his son and gives him these words of wisdom: “Never underestimate the other person’s insecurity.” Instinctively, we picture the father in faded jeans and a plaid shirt, eyes squinting into the sun.

In the years to come, that young man—heading off to study art history at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts—would become a famous and long-standing writer at the New Yorker, loved by some and loathed by others for his distinctive style, which is imbued with so much cloying nostalgia that it makes the teeth ache. (You can guess which set I belong to.) The writer is Adam Gopnik, and the story above, embellished only slightly by me, opens his memoir At the Strangers’ Gate. The story is bunk. Sure, it’s true in its bare details: he did, in the summer of 1980, depart for New York with Martha Parker, to whom he remains married. But while the opening vignette gives us an impression of a wide-eyed youth being sent off to the Big City by his plain-spoken, salt-of-the-earth father, the reality is that Gopnik’s father was the late Irwin Gopnik, at the time an associate professor of English at McGill university, well known for his dashing and dramatic outfits topped off by fedoras and overcoats with built-in capelets. Gopnik’s mother, Myrna Lee Gopnik, is a renowned linguist and professor emerita, also at McGill, where Gopnik got his BA. He and his five siblings grew up in Montreal’s famous Model 67, a landmark experimental housing structure in the Brutalist style. It’s highly likely that Gopnik, the child of two well-known, artistically-minded academics at a prestigious university, would have visited New York often throughout his life, or at least not thought of it as particularly exotic. But of course, the tale of a young shrub from some mythical heartland receiving homespun wisdom from his father before setting off into a perilous urban landscape is much more romantic to the average reader.

Most large cities have inspired fiction and non-fiction, but New York may be the city that’s been written about the most. The sheer density of New York, and its history as a portal for immigrants entering the United States, has helped create a unique cultural and political ecosystem that has both attracted and repelled millions, inspiring a constant stream of literary output. The typical New York story drips with nostalgia. Everything was better, we are told, in the old days. The old days might be the 1900s (as hard as it is to romanticize tenement life), or the 1920s, or the 1960s or the 1970s, and so on. There are, of course, unsentimental portrayals of New York, or portrayals of it simply as a city, but these are not the most popular, or best known. In Joshua Marston’s deeply underappreciated film Complete Unknown, characters make their way through the city in their everyday lives: the result is a more intimate, complex view of New York. But the misogyny of critics who hated the central female character (she shows no remorse for being an adventurous reinventer of herself; we can only imagine that a male character in the same position would have been declared daring and admirable) means that the subtleties of the film’s relationship to the city have largely gone unnoticed. Most audiences want to hear about a New York that is charmed by, even obsessed with its own past; writers and filmmakers over decades have obliged.

Gopnik is a typical example of this latter tendency. In his hands, New York is frozen in amber, part Gershwin melody, part Sinatra paean, and mostly a fantasy that is sometimes so unreal as to be ludicrous. Consider, for instance, how he writes about his wedding to Parker in December of 1980: “When I say ‘married in New York’ I know that it might sound rather like top hats and morning coats and a ceremony at St. Thomas Episcopal. In fact, on a bleak December day, we would take the 5 train to City Hall…” Who in the 21st century actually pictures “top hats and morning coats” when someone says that they got married in New York? Even in a pandemic, we haven’t retreated so far into imagination that we think New York is actually trapped in the 1920s. That’s on you, dude, all on you.

Gopnik’s genius, and the reason he’s the target of both love and hate, is that he has figured out how to distill and market nostalgia, a very particular kind that evokes no sadness or sense of loss, only a warm and fuzzy feeling resolutely free of pain. This isn’t even entirely specific to his writings on New York, but apparently to his attitude toward life in general. In 2003, Gopnick was living in Paris, which had just experienced a heat wave so intense it killed tens of thousands of people. Asked for comment on this devastation, Gopnik stated dreamily: “Even in the worst heat of years past, a cool, sad breeze always swept through the city around midnight—we used to go to St. Sulpice late at night just to watch it arrive and shake the trees. But this summer it was nowhere to be found, a lost friend, and the sizzling day sank into a torpid night, just like back home.” In other words: Yeah, who knows, but look at all my pretty words.

Gopnik is mostly known as someone whose life and experiences stand in for a particular kind of New Yorker: charming, playful, a devotee of the arts, well read, always able to see only the sunshine, never the clouds. He fulfils many writers’ dreams of becoming successful and frolicking with the rich and famous. In Strangers’ Gate, he spends an entire afternoon with Richard Avedon, recounting their time involving people on the streets who failed to realize they were having their portrait taken by a famous photographer. Even when he said to them, “I’m Avedon,” his words were greeted with blank stares. Gopnik is always creating a nostalgic New York, even milking nostalgia from the present: he is with Avedon, but his writing about the moment is itself meant to evoke a sense of the past; he notes, with a sense of Oh, remind me to tell you, Avedon would die a few days later. One imagines Gopnik’s mantra for New York is always: it was, it was, it was.

My little town blues

Are melting away

I’ll make a brand new start of it

In old New York

— Liza Minnelli, “New York, New York,” by John Kander and Fred Ebb

In 2007, a blog simply titled Jeremiah Moss’s Vanishing New York began the work of chronicling the gentrification that was wiping out small businesses and thus, for its pseudonymous creator, a central part of the very character of the city he loved. His online writing continued for a decade until Moss revealed his real name—Griffin Hansbury—to, of course, the New Yorker.

The blog eventually became the book Vanishing New York and in it, Moss quotes, of course, Adam Gopnik: “New York is safer and richer but less like itself, an old lover who has gone for a face-lift and come out looking like no one in particular. The wrinkles are gone, but so is the face… For the first time in Manhattan’s history, it has no bohemian frontier.” Gopnik and Moss are a few decades apart in age, and Moss’s sensibility is more punk rock than classical, but he has absorbed Gopnik’s vision of what New York was and should be, with a slightly grungier aesthetic.

Moss, like Gopnik, came to New York from elsewhere—Massachusetts, in his case. Unlike Gopnik, Moss at least admits to having visited the city often as a child, but he also brings with him, as an adult entering to live in it for the first time, an amberized vision of what the city should be. It can be hard to tell which comes first, the vanishing of a popular Italian bakery or the melting away of the Italian community that kept it afloat for decades, but disappear they both do. For Moss, the loss of small businesses and landmark architecture, replaced by what are to him the faceless and heartless abstractions of contemporary buildings, is a phenomenon worth raging about. And rage he does, fulsomely and constantly, earning millions of followers and spawning a larger and more public movement to keep the city’s “essence,” as many see it, from vanishing.

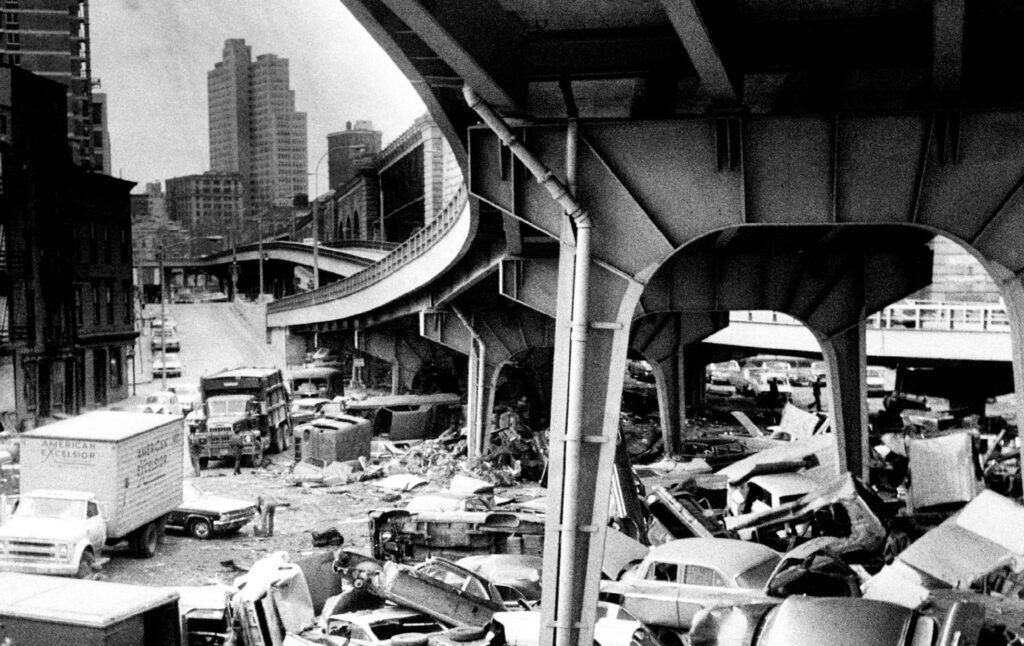

Moss also came to New York on a bus, in the 1990s, in new black leather, determined to fit into what he thought would be the image of the kind of New Yorker he would become. (Along the way, he also transitioned, lending his journey both a poignancy and a meaning that’s hard to miss.) According to him, he moved “unaware that the early 1990s was quite possibly the worst moment to get attached to New York.” What counts as a heyday and for whom is never quite clear, but Moss’s idea of what is “disappearing” in New York is derived from what he cheerfully admits is nostalgia. “My city,” he writes, “is the city of dark moods, scrap yards, and jazz. Of poets, painters, and anarchists. Of dirty bookstores, dirty movies, and dirty streets. It’s also a working-class city peopled by men and women who love with a tough love, in thick accents and no time for bullshit. Of Gershwin’s ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ trumpeting over black-and-white Manhattan, and Travis Bickle’s taxi roving through the steamy rain, that grimy yellow splash. It’s the city of Edward Hopper’s melancholy rooms and Frank O’Hara’s ‘I do this, I do that.’”

But whose New York is this? What gives an outsider the right to decide that the early 1990s were the city’s “worst moment,” when he wasn’t there to live through all the decades prior? Dirty streets and grime might be Moss’s fantasy, but millions of New Yorkers have, for decades, been fighting to not have to suffer them. Constant noise and the smell of piss and shit are rarely romantic to those who have no choice but to live in those conditions full time. (Elsewhere, Moss freely admits he doesn’t care about any of the other boroughs outside Manhattan, showing great disdain for a giant swath of people and places who actually create the vibrancy of New York.) Moss is all grit and punk, writing enthusiastically about the grunge and tough life of the streets and the noise and the tumult, but with a lack of any awareness that, perhaps, many actual New Yorkers might not particularly want a grittier New York, just one that’s actually affordable and safe. In the hilarious Netflix series on Fran Lebowitz, Pretend It’s A City, Lebowitz talks to Martin Scorsese—her friend and the director of the series—about how she chose her apartments. When friends pointed out she could get a much cheaper apartment in their (much worse) neighborhoods, she would respond, “Yeah, but I don’t get raped.”

Between Gopnik’s visions of top-hatted weddings and Moss’s rhapsodies to excrement-caked streets, whose New York counts as reality? Of all the portrayals of the city, Woody Allen’s vision of New York is perhaps most emblematic: his celebrated film Manhattan is self-consciously about nostalgia in its use of black and white and its iconic shot of the Queensboro Bridge. (The movie itself, mostly about a relationship between a 42-year old man and a 17-year-old high schooler does not, um, age well). But while we might now want to deny any artistic debt to Woody Allen, his films about New York from Annie Hall onwards have nevertheless defined a particular kind of New York, about men and women who are intellectuals and who are intellectually driven to theorize their relationships and the world around them—a world that is also, incidentally, utterly shorn of any people of color. (Any drinking game involving “Spot the Person of Color in a Woody Allen Film” would leave one sadly nursing a full glass at the end.)

Ultimately, all representations of New York are just that: representations. And yet, it’s incorrect to think that these nostalgic fantasies never have any impact on the real life of the city. We can see, in the effect of Moss’s work, that there are actual policy decisions to be made or not made based on what people like him determine to be the ideal New York: a city bustling with small mom and pop shops everywhere, no chains to speak of, and beautiful architecture. But is this always a good thing for people who live in New York? Who determines what architecture is “beautiful” and what isn’t? Small businesses can seem charming, but they’re generally hostile to raising wages and unionization. Additionally, whether or not you like your local mom and pop or boutique store can depend on how you’re treated there based on factors like race and gender. In Chicago, the gay area formerly known as “Boystown” (renamed “North Halsted”) remains teeming with gay “small businesses” like the notorious Beatnix that have been permitted to indulge in their blatant forms of racism and discrimination.

And “small business” does not always mean affordable: that overpriced coffee house or expensive store devoted to artisanal home goods might be able to afford the rent, but they’re out of reach for most who trek to the nearest Target or 99cent store for towels. Navigating a landscape composed entirely of tiny, cute “local” businesses (probably selling goods made by tiny, cute children in remote countries) can actually be a nightmare, especially for those who are minorities in that neighborhood. It also may be a mistake to focus on the nostalgic resonance of a place over the actual function it serves in the lives of people who use and inhabit it. Aisling McCrea has written about the role of Starbucks and other “soulless” corporate stores in creating places where real people actually do congregate and create community. Corporations as emanations of capitalism are evil, yes, but as entities on the literal ground, they can become fungible, fluid places that actually give life to people. If this life-giving effect is what we’re seeking, is it right to assume that ossifying old businesses, institutions, and structures is always the best way to do it?

Moss’s vision of the city he actually lives in is bizarrely mediated through a fictional, literary, and cinematic lens that insists poverty should be the definition of authenticity. This is a strange denial of reality, both because many New Yorkers today are middle and upper class, and also because romantic and artistic visions that dominate our backward-looking conceptions of New York were often created by writers and filmmakers from those very same classes. This artistic legacy goes back literally for centuries: Edith Wharton was born into the New York high society she portrays in works like The Age of Innocence. Martin Scorsese and Woody Allen, of roughly the same generation, came from middle class families, and grew up in a time when New York more readily extended artistic, creative, and educational opportunities to people who were not already wealthy; it was these opportunities, rather than any unusually deep authenticity about their perception of New York or any connection to its “working class” heart, that allowed them to become renowned filmmakers.

Because so few can even afford to live in New York’s fashionable areas, much less make and widely distribute art there, presentations of New York have generally been limited to a narrow band of experience. The consequent visions of the city are like Russian dolls, one inside the other: Moss is nestled in Gopnick, who’s nestled in Allen, and so on down the line: visions of New York that are based as much, if not more, in references to other art made about New York as they are in its day-to-day contemporary realities.

And what costume shall the poor girl wear

To all tomorrow’s parties

For Thursday’s child is Sunday’s clown

For whom none will go mourning

—“All Tomorrow’s Parties,” The Velvet Underground and Nico

In one scene in Pretend It’s a City, the iconic New Yorker Fran Lebowitz towers above a miniature version of the city in the Queens Museum. Off-camera, the director asks, “Why do you think so many young people are still coming to New York? What’s here?” She responds, “New York! That’s what’s here!” Elsewhere, she talks about convincing the child of a friend to move back to the city. When told it’s too expensive, she scoffs that, no, anyone can make it work.

In contrast to both Gopnik and Moss, Lebowitz is less invested in a nostalgic or mythic New York, and more invested in complaining about why the here and now generally sucks. She has consistently railed against every mayor of the city, with particular ire towards Michael Bloomberg. But Lebowitz came to New York in 1969, when people were often flocking to the city because it was everything their hometowns were not, where queer and other marginalized people could find affordable places to stay, and sustain cultural and political engagements of all sorts. People like her weren’t chasing a dream but escaping a nightmare: New York let them in and let them be whoever they wanted to be, as corny as that sounds. Today, you can still live in New York but you might have to forego Manhattan and the trendy parts of Brooklyn (neither Gopnik nor Moss spend much time on the outer boroughs, which are bustling, vibrant, and lively—just not with the people they might want to be seen with or to be). And as developers cast their eyes on Queens and other places long considered to not be really that “New York” (again, according to whom?), longtime city residents face the constant threat of being priced out. Vast tracts of Manhattan are unoccupied, owned by billionaires interested in buying but not actually living in property. For many New Yorkers like the journalist Kevin Baker, the vitality of New York appears to be ebbing, sapped and sucked dry by those who own it but don’t care about it. Baker writes, “Cities are all about loss. I get that. Intrinsically dynamic, cities have to change, or they end up like Venice, preserved in amber for the tourists.” But change itself has to be dynamic, a movement towards the next iteration, driven by the daily lives of people who dwell there—while New York, for Baker and others, seems to be grinding to a halt. There’s a difference between the gentrification that Moss and his ilk complain about—where old things disappear and new things appear in their place—and the more deadly sort which is really just about making things disappear without actually replacing them with anything.

The pandemic has only worsened the inequalities: Bloomberg Media reports that “more than two-thirds of New York City’s arts and culture jobs are gone.” (The report is oddly and particularly distressed by the fact that most of the workers in this sector are white and male.) Those with the means and resources to leave the city at the height of the pandemic will also be able to return once things ease up again, but in the meantime, a city so dependent on cheap, mobile, and mostly migrant labor (as in, migrating from other cities and countries) may feel the force of large swathes of workers having to leave permanently, as well as entire positions being cut. But it’s also just as likely that there will be plenty of incoming people to replace people and jobs because, well, it’s New York.

Whether or not New York endures as a vibrant cultural, economic, and political center remains to be seen. But rather than mourn the possible demise of the city—or more specifically, the demise of a nostalgic ideal—we might want to ask ourselves: how do we replicate what New York offers, even in our different cities or much smaller towns? Consider what makes a city like New York distinct: largely, it’s the fact that its residents can zip around it, absorbing variant and variable parts without much trouble, because there is a (comparatively better) investment in public transportation than in most metro areas. Yet, elsewhere in the United States, most Americans remain suspicious of transportation that’s not tied to cars: for the wealthy, this suspicion is largely a fear that the poor might infiltrate well-manicured suburbs or the exclusive domains of their city. In Chicago, where I live, it can take a couple of hours to make it from the poorer west or south sides to the more affluent (and much whiter) north side, and public transportation worsens the further you get from that area. As for New York’s supposed dominance in the “creative arts”: What if we invested in not just the arts, but in a public school system that cared about its students across the entire city, municipality, or county, not just in a few neighborhoods? (For all its diversity, New York has one of the most segregated public school systems in the country, a testament to its growing inequalities, and arguably also a factor in its gentrification and decay.)

The fixation on New York as a cultural epicenter makes sense given what we know has emerged from it: the Velvet Underground and John Cale, Annie Hall, Keith Haring, and so much more. Much of what makes New York New York cannot be replicated. What makes a city truly great is the ability to get lost in it, a lostness not defined by geography or streets, but by intellectual and social boundlessness. That’s not an experience easy to replicate in most cities: New York has always been a city of escape. Still, if we give opportunities to other places to nourish the particular uniqueness that New York has managed—through a combination of chance, brutal charm, and openness to outsiders—to wrest for itself, we might be less invested in the fantasies of New York conjured by writers like Gopnik and Moss, fantasies which ultimately only participate in a kind of Nostalgia Industrial Complex, serving little purpose beyond selling copies of middling books. We can create art, even great art, unaided by the stench of piss and shit in the streets, in the warmth of well-heated apartments with proper doors and sanitation and an affordable coffee shop—even a chain one!—down the street. Poverty and instability suppress the free exercise of creativity and talent more than they enable it: we might recall that both Karl Marx and Vincent Van Gogh would never have produced the work they did without generous benefactors.

There will never be another New York, sure. But there will also never be another Kolkata, or another London or another Berlin. Every place is rooted in its people and its things, its buildings, its tools of mobility, its coffee shops and museums and bookstores and waterfronts and more, but the loss of all that stuff is not what kills it. What kills a city is the force of nostalgia, when a place becomes an idea instead of a vital, throbbing and almost organic creature that lives and breathes with complex and complicated ecosystems that often, yes, vanish, only to be supplanted by something else. Writers write to keep alive our memories of what a city once was, what it is, and what it could be, but if we are to think seriously about how to sustain not just cities but their vibrancy too, we must focus on how to do that without depending on writerly fantasies. After all, at the end of the day, in that limitless interplay between a city that writes itself into writers and writers who write themselves into cities: Who is nostalgic for whom?