In much the same way that the concrete tower blocks of Moscow remain visible emblems of Soviet communism, the boxy Cape Cod houses of suburban Levittown, New York have stubbornly persisted as symbols of American capitalism. This was by design: despite being more similar to their Warsaw Pact brethren than anything else—mass-produced, utilitarian, and, depending on the specific design, either cozy or alienating—these pieces of early Cold War Americana were intended from the beginning to instill confidence in the free-enterprising American way, offering a measure of economic prosperity in exchange for allegiance. The man behind the prototypical suburb, real estate magnate William Levitt, proudly boasted that, “No man who owns his own home and lot can be a communist.” Richard Nixon, arguing the merits of his country’s system with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in the legendary 1959 “Kitchen Debate,” proffered a replica of a similar modest Long Island prefab (the “Leisurama”) as evidence that only the free market could provide the masses with a life of such comfort and ease.

70 years and six additional Levittowns later, the suburbs have retained their image in the collective imagination as lily-white conservative bulwarks against radicalism. And not entirely without reason: my suburban hometown, just a few minutes drive from Levittown on Long Island’s South Shore, was just as much a Trump stronghold as Pennsylvania fracking country. In the weeks leading up to November 3rd, “Keep America Great” and “Trump-Pence 2020” banners hung from the balcony of the waterfront catering hall (thankfully, I don’t think anyone was getting married there at the time). Over the summer, “Thin Blue Line” flags and other anti-Black Lives Matter paraphernalia were common pieces of outdoor home décor, to the point where you might have believed there was a new holiday with black, white, and blue colors. One particularly creative Halloween lawn display I spotted last October featured a life-sized Hillary Clinton mannequin in shackles and a striped prison jumpsuit.

Politicians also tend to operate under the assumption that all suburbs are the domain of middle-to-upper class whites with a strong aversion to rocking the boat. As Republicans sought to exploit the backlash to a perceived loss of “law and order” in the wake of last summer’s racial justice protests, suburban communities across the country became flashpoints in the tumultuous lead-up to the presidential election. While channeling suburban anxiety into higher turnout has long been a component of GOP strategy, it reached a degree of bluntness under Donald Trump that verged on ludicrous. At a July 29 campaign event in Midland, Texas, Trump warned his audience that the Democrats want to, among other things, “indoctrinate our children, defund our police, abolish the suburbs, [and] incite riots,” but mercifully reassured them that “there will be no more low-income housing forced into the suburbs” because he had “just ended the rule” that allegedly mandated this. The McCloskeys, the St. Louis couple famous for pointing a rifle and pistol at Black Lives Matter protesters from their front lawn, hammered the same point just as unsubtly during their primetime speaking slot at the 2020 Republican National Convention:

What you saw happen to us could just as easily happen to any of you who are watching from home… [The Democrats are] not satisfied with spreading the chaos and violence into our communities—they want to abolish the suburbs altogether by ending single-family home zoning. This forced rezoning would bring crime, lawlessness, and low-quality apartments into now-thriving suburban communities.

The McCloskeys’ racist fear-mongering does not correspond to any real threat, but that’s not to say that the suburbs are the comfortable and frictionless places that Leave it to Beaver made them out to be. There are meaningful differences between the suburbs of 1959 and the suburbs of 2021. As the anthropologist and journalist Brian Goldstone points out on a recent episode of “The Politics of Everything” concerning the “strangely persistent myth of the suburbs:”

Poverty in the suburbs nationwide has risen dramatically over the last couple of decades, to the point that today, there are roughly 3 million more people who are poor in the suburbs than in urban centers. In Atlanta… poverty in the suburbs rose by 159 percent over the last 15 years

In the wake of the 2008 foreclosure crisis, Goldstone notes, thousands of suburban homes were converted into rental properties that low-income residents—many of them pushed out of cities during the recession—struggle to afford. “Hidden homelessness” has become a pervasive problem, in which unhoused people find themselves resorting to extended-stay motels and other makeshift arrangements. The necessity of car ownership, which racks up gas and maintenance costs, leads the suburban poor to sacrifice food and sometimes housing altogether. The cliché of the two-cars-in-every-garage lifestyle has obscured an urgent need for radical reform.

The resurgence of the American left in recent years has thus far been a primarily urban development—the members of the Squad all represent congressional districts located in large cities, for instance—and while there is hope that (at least some) well-to-do suburban residents are turning away from Trumpism, on the whole there’s scant indication that many of them will assume the mantle of vanguard of the proletariat anytime soon. If anything, an influx of wealthy suburbanites into the Democratic coalition has bolstered the dominant position of the party’s moderates. But the suburbs don’t have to remain stuck in a reactionary and unequal quagmire. On the contrary—the fact that the limited and flawed welfare state policies of the New Deal and postwar eras enabled the rise of the suburbs shows that left-wing ideas can benefit them just as much as any other type of community. Far from abolishing the suburbs altogether, an even more ambitious democratic socialist platform would be instrumental in addressing the profound inequities of both the first suburbanization and their current state, therefore ensuring a high standard of living for all.

In May 1946, just months after the end of World War II, an act of Congress formally declared the shortage of housing a national emergency. A decade earlier, the Great Depression had slowed new residential construction to a trickle, and the subsequent switch to a total war economy diverted much of the country’s industrial resources to the manufacture of armaments. By the end of 1946, according to a report presented to the House of Representatives in February of that year, 2,900,000 married veterans would be in need of affordable housing. A Senate report published around the same time concluded that government intervention was a continuing necessity. “No amount of propaganda by real estate and mortgage lobbyists,” the report reads, “can cancel the utter failure of the private building industry to make modern, decent, low-cost shelter available to the average family.” It also recognized the potentially explosive consequences of an inadequate response to the crisis:

If Americans ever lose faith in the free way of life, it will not be because they have been converted by totalitarian arguments, but because vested interests within the democratic system raise intolerable barriers to the satisfaction of popular needs. The democratic process will then fall under the sheer weight of accumulated frustrations and resentments.

In short, the choice was between political upheaval and building millions of houses. While Congress responded to the acute shortages with the Veterans’ Emergency Housing Act—which enabled the Truman administration to orchestrate a rapid but insufficient expansion of the housing stock through the temporary retention of emergency powers granted to the executive—the groundwork for a longer-term solution had in fact already been laid with the passage of key legislation during the New Deal and war years. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), introduced in 1934, established a mortgage insurance program that reduced risk to lenders in the event of default, greatly increasing borrowers’ access to the credit necessary for home ownership. More manageable 30-year payment plans became the new national standard, and, consistent with the first-term Franklin D. Roosevelt administration’s emphasis on government partnership with private industry, the agency spurred construction by offering generous subsidies to developers.

Perhaps the most ambitious social democratic program of the first suburban wave, however, was the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, better known as the G.I. Bill. In contrast to Roosevelt’s original means-tested proposal, the final version of the bill provided immediate, direct financial benefits to millions of World War II veterans re-entering civilian life: they could collect a year of unemployment compensation, receive stipends covering tuition and living expenses at colleges and trade schools, and—most crucially for our story—take advantage of low-interest mortgages. The most favorable terms were given to those looking to build new homes outside of established urban centers, reflecting the federal government’s desire to relieve overcrowding in cities, as well as the influence of a current in prewar urbanism that viewed moderately dense, semi-rural planned towns as a salutary alternative to the industrial megacity (the New Deal’s Resettlement Administration briefly experimented with the construction of model “greenbelt communities,” themselves based on the lush “garden cities” that began to spring up around London in the late 19th century).

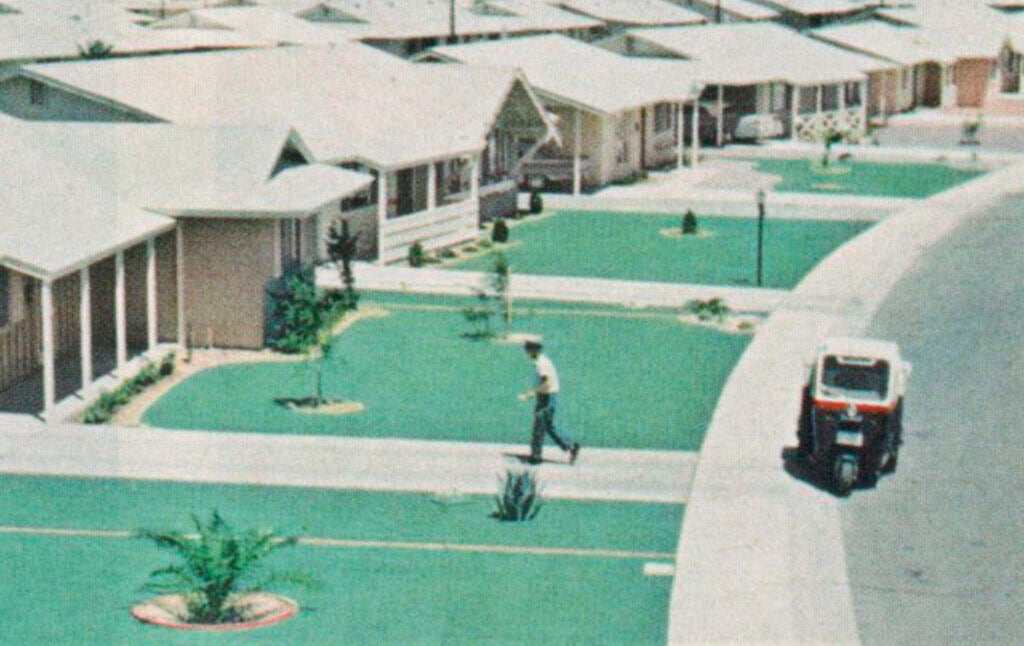

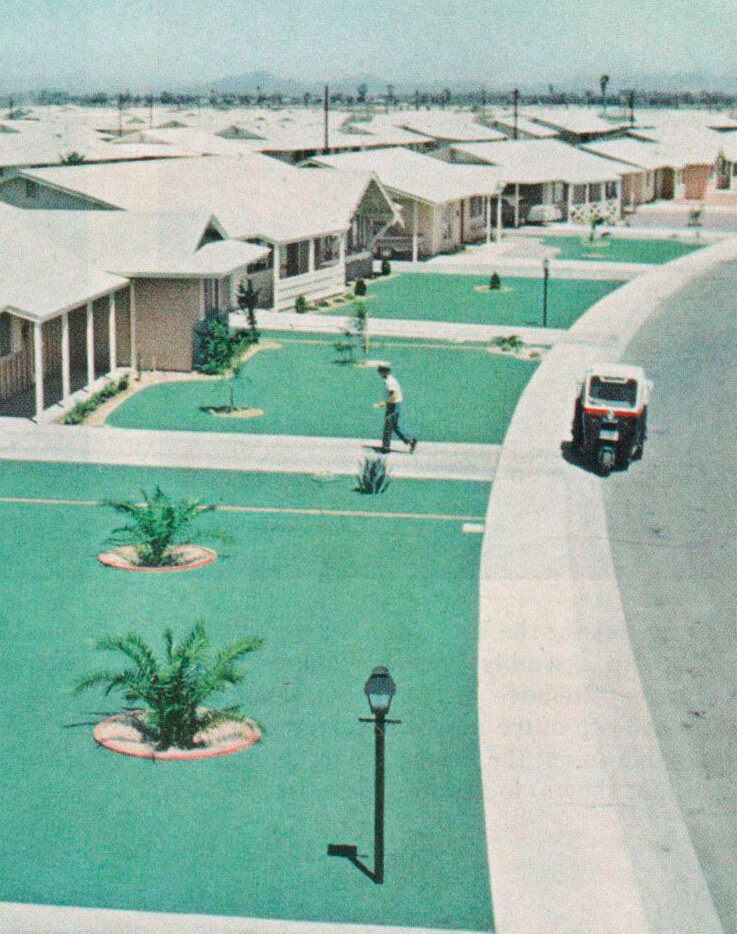

The result was nothing less than a seismic shift in the American landscape: the birth of the modern suburb. Fueled by FHA subsidies and making extensive use of cutting-edge mass production techniques—at peak efficiency, Levitt’s assembly lines were able to put up a house frame in just 16 minutes—entire towns of uniform Cape Cods and bungalows sprang up virtually overnight. Veterans receiving G.I. Bill mortgages could move into a $7,990 Levittown house with no down payment and immediately begin reaping the benefits of the emerging suburban consumer culture. Initially bare-bones developments were soon flush with government investment in the form of brand new public schools, public parks and swimming pools, expanded networks of affordable state universities, and the sprawling Interstate Highway System. The Baby Boomers who came of age in these new communities benefited from a degree of state-supported prosperity that for their parents, children of the Depression, would have been almost unthinkable.

But this prosperity was of course not universal, and for a considerable portion of the American population, suburbia’s white picket fences doubled as miniature Berlin Walls. Racism marred the first wave of suburbanization, with a combination of social pressure and legal prohibitions working to keep the first suburbs as close to 100 percent white as possible. Until the 1948 Supreme Court decision in Shelley v. Kraemer ruled the practice legally unenforceable, FHA subsidies for developers came with instructions that no home in a proposed subdivision could be sold or resold to people of color, introducing residential segregation into previously more integrated parts of the country. Black veterans, on the whole, were also barred from taking full advantage of the GI Bill due to racist implementation: they were more likely to be dishonorably discharged than white veterans (and thus disqualified from receiving benefits), and the technicality that the V.A. could cosign but not guarantee a mortgage all too frequently put suburban homeownership out of reach. The few non-white families to move to suburbia in its first two decades were often met with outright vigilante violence at the hands of their neighbors—arson, death threats, burning crosses—to such an extent that historian Arnold Hirsch labeled the 1940s and 1950s “an era of hidden violence.” By the late 1960s, a social dynamic that would influence the trajectory of American political and social life for decades had already taken shape: an overwhelmingly white middle class with equity in houses was concentrated in thriving suburbs, while a multiracial working class remained in cities facing rapidly shrinking tax bases and deteriorating social services.

With the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968 and other anti-discrimination laws in the wake of the Civil Rights movement, home ownership outside the city became an increasingly viable possibility for people of color, leading to the slow but steady growth of middle-income and rich suburbs with non-white majorities. By 2010, in the country’s large metro areas, majorities of Black (51 percent), Asian (62 percent) and Hispanic (59 percent) Americans resided outside of the urban core. A slim majority of all immigrants also live in suburbs, whether affluent professionals from India and China or resettled refugees from Central America.

Modern suburbs face a unique mix of challenges, including holdovers from the first wave of development and new problems arising from broader economic changes in recent decades. The increasing poverty rates are strongly connected to the gentrification of cities: as rents and living expenses rise, a growing number of working class-city dwellers have found themselves displaced to adjacent suburbs, which often lack the social support institutions and public transport connections of more central locations. Poverty and homelessness have become increasingly “suburbanized,” while the resources to ameliorate them have not. In spite of greater diversity on a macro level, stark racial segregation persists. A thorough undercover investigation by Newsday found substantial evidence that real estate firms on Long Island were illegally steering white prospective clients into white-majority neighborhoods, and people of color with identical profiles into more integrated towns (often the same ones that agents would disparage in coded language in front of whites). As a result of these less outwardly visible forms of discrimination, Nassau County holds the ugly honor of being one of the nation’s most segregated places: Levittown remains about 83 percent white today, and Massapequa, where I grew up, about 96 percent.

In their pervasive racism, stifling social norms, and environmental toll, the suburbs have come to embody the worst ills of American society. But there’s another lesson to be learned from the history of the suburban project. Many of America’s early- to mid-20th century experiments in social democracy—a highly uneven mix of visionary ideas (see the Tennessee Valley Authority and the electrification of rural America) and business-enriching reforms (see the New Deal’s prioritizing of private construction over public housing)—were able to deliver adequate housing and a decent standard of living to millions of people who otherwise wouldn’t have had them. Suburbia as we know it is just as much the product of conscious government direction as of investment decisions made by real estate titans. There’s no reason, then, why a bold democratic socialist vision couldn’t tackle the ugly legacies of the first wave of suburban development. With a majority of Americans living in suburbs—encompassing everything from quiet cul-de-sacs to impoverished outskirts—these communities and the distinct problems facing (and caused by) them must figure into the proposals of any socialist movement in the United States.

A new agenda for the suburbs, drawing on both the historical precedent of the New Deal and more contemporary ideas, would by no means be constitutive of socialism on its own, but by investing the wealth of society to maximize collective well-being, it would aim to realize socialist principles of solidarity and egalitarianism.

In order to tackle housing insecurity and rising home prices in suburbs—both trends that have intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic as the economy craters and wealthy urbanites abandon the cities for more spacious digs—there will need to be another expansion of the stock of affordable units. Many homes and apartments currently sit empty of course, but climate change will make certain parts of the country and world uninhabitable, necessitating increased density in temperate regions. A socialist solution to this grim state of affairs may have to involve building non-market housing, including in suburbs.

Historically, public housing in the United States has had a less than stellar reputation—”projects” like the now-demolished Cabrini-Green and Robert Taylor Homes in Chicago were virtually synonymous with dilapidation—and any push to introduce public housing in suburban communities would have to grapple with inevitable pushback from homeowners’ associations and ordinary residents alike. Of course, a good portion of this lingering stigma is rooted in racism, but it’s also true that many of the 20th century’s large high-rise complexes were simply built to be neglected. Designated low-income public housing tends to place a large number of impoverished people in a single location, and concentrated poverty in turn exacerbates a whole host of social ills. Stranding the destitute in areas lacking essential infrastructure—good public schools, clean tap water, grocery stores—is the problem, not public housing.

Socialists tend to prefer universal programs over means-tested ones, in part because they are more efficient and harder to delegitimize through accusations of benefitting the “undeserving.” The same logic applies here: aesthetically pleasing, well-maintained public housing open to residents of all income levels and subject to strict federal level enforcement of the Fair Housing Act will not only encourage racial and economic integration, but also have the best chances of success. About a century ago, Vienna’s Social Democrats put up mixed-income, municipally owned residential complexes (notably the Karl-Marx-Hof) that still offer tenants comfortable and visually appealing places to live. And it’s possible to build without enriching the private developers responsible for segregating the suburbs and gentrifying the cities. A proposal by Peter Gowan and Ryan Cooper for the leftist think tank People’s Policy Project outlines a plan for municipal governments—with capital grants and loans from the federal government—to construct 10 million such units, financed in large part by simply repealing the Trump tax cuts. Ways of operating could vary with differing local circumstances and preferences: possibilities include municipal ownership, as in Gowan and Cooper’s plan, or limited-equity cooperatives, in which unionized tenants collectively oversee day-to-day functions.

Beyond providing democratized—and eye-catching—public housing, a socialist suburb would seek to negotiate a more sustainable coexistence with the natural world, in marked contrast to the first wave of suburbanization’s brutal overpowering of it in service of a perverse notion of “development” as the realization of humanity’s potential. Partly a hubristic belief in the limitlessness of economic growth and partly a cynical justification for the conquest of supposedly “underdeveloped” indigenous peoples, the ideology of civilizational progress that undergirded the growth of the first suburbs has resulted in the wanton destruction of nonhuman life and poses an increasingly grave threat to the existence of our own species. And in spite of more sophisticated technology to mitigate their impact on climate, today’s suburbs still contribute to environmental degradation through adherence to traditional auto-centric design. One 2018 study found that while Salt Lake City and its surrounding suburbs experienced comparable population growth over the same period, the suburban end of the expansion—by putting cars on the road and building larger houses requiring more fuel to heat—was responsible for an increase in emissions not seen in the city proper.

Nurturing the planet’s fragile ecosystems and meeting human needs without falling into the trap of endless development will require a drastic restructuring of the existing built environment, optimizing what we already have instead of continuing our encroachment on wild habitats. To accomplish this, a socialist Green New Deal would need to undertake a series of ambitious public works projects aimed at making car-free suburban living not just a possibility, but the norm. Expansive networks of electric trams, trains, and buses which are free at point of use (as they are in Tallinn, Estonia) could link residential neighborhoods and commercial districts within suburban counties, as well as improve connections to the public transit system of the greater metropolitan area. Such a plan might also help remedy the inequities in commuting time and costs that stem from residential segregation and the resultant spatial mismatch between jobs and housing. (Evidence from the Estonian case on whether free public transit increases mobility for low-income residents is mixed, but in any case the design of future systems must account for the ways in which gaps in coverage have worsened structural inequality along lines of race and class).

Pedestrianizing busy streets and expanding bike lanes to cover entire municipalities could not only end the SUV’s reign of terror, but also introduce a certain joie de vivre into the previously atomized suburban lifestyle. If a town built around the car reflects a mode of being that isolates the individual in a private bubble of self-interest, a walkable socialist suburb would emphasize the neighborhood as a living, breathing public space: a place for chance encounters with friends on the way to work; a place for leisurely strolls in the fresh evening air (now free of noxious fumes); a place for fountains and trees and buzzing cafe terraces. Somewhat paradoxically, a sustainable futuristic suburb would be similar in layout and function to the beloved historic quarters of the world’s old cities, from the maze-like hutongs of Beijing to the medieval alleyways of Barcelona.

There’s also the matter of protecting suburban communities from extreme weather. Adapting to rising temperatures will be a major undertaking, but a climate change mitigation corps—created as part of a federal program offering unionized, well-remunerated positions—would be equipped to take on the task. Much of this work would involve retrofitting suburban homes built for a world unaware of the threat of global warming: depending on the region, this could mean installing air conditioning in areas prone to dangerous heat waves, or raising houses in low-lying coastal flood zones (two-story houses awkwardly standing on stilts were a common sight in my neighborhood in the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy). Even tried and tested low-tech solutions like planting trees in forests struggling to regenerate, or near shorelines to slow erosion, could go a long way towards repairing the ecological destruction wrought during the first phase of suburban development.

But, as previously mentioned, the socialist suburbs of tomorrow should be more than places to eat, sleep, and catch an electric train to the office downtown. Leisure is essential for maintaining well-being, as is a sense of being integrated into a supportive community. There’s a reason why paring down the grueling 12- to 16-hour workday was one of the crowning achievements of the first socialist parties. Given the wealth and productive capacities of 21st century America, no one should be working multiple jobs or forgoing weekends when they could be using that time to follow their passions, either individually or together with friends and neighbors. A more egalitarian distribution of resources under socialism would mean shorter workweeks, freeing up time for creativity and strengthening social bonds.

Through a more ambitious permanent version of the original New Deal’s Works Progress Administration (in which the government would employ artists, writers, musicians, and performers to produce works for the enrichment of the public), a socialist platform could transform today’s sleepy commuter towns into vibrant centers of cultural and intellectual life in their own right. Enabling budding artists to make a living in suburban towns and building up infrastructure to support them—exhibition halls for visual arts, auditoriums for free concerts and drama—would pepper the former monotony of suburbia with distinctly local cultural institutions. Generous support for public events proposed and organized by residents would be indispensable: bake-offs and DIY-film screenings, pop-up ice rinks and experimental music festivals, all funded by municipalities and attracting locals and visitors alike. Far from mandating conformity to state-sanctioned forms of expression, a socialist project would invest the wealth of the community into a panoply of creative endeavors reflecting the actual diversity of today’s suburbs.

Above all, the suburbs of a socialist future should be beautiful. They should lift the spirits of the people who live in them through design that imbues everyday routine with a sense of joy. The lonely private homesteads of the 20th century would give way to democratically luxurious neighborhoods, with architecturally innovative housing that complements the surrounding natural landscape and fosters a sense of community. You might choose to live in a cozy single-family house just outside Milwaukee, connected to other cozy single-family houses by a garden for flowers and vegetables; you might tend to the rose bush while your affable next-door neighbor picks a few ears of corn to grill at dinner. Or perhaps you might settle in a handsome adobe brick row house on the edge of Albuquerque, just a 15-minute electric tram ride to the local theater where your friend is putting on an endearingly terrible avant-garde play. After a long but rewarding day of soil conservation work, you might unwind by biking down the car-free Ocean Parkway to Jones Beach, where you can faintly make out the skyline of Manhattan through the misty air.

These are only a fraction of the possibilities for the socialist suburbs, but one thing is clear: reimagining suburbia—the embodiment of both America’s technical achievement and its authoritarian tendencies—will be an essential part of the movement towards a just and prosperous future.