Larry Hogan and the Mushy Middle

The Maryland governor’s COVID-era memoir is a study in moral cowardice.

Larry Hogan enjoys being the governor of Maryland. He shows a fondness for wearing shirts, jackets, and even hard hats with the word “Governor” on them. He savored the first time his wife called him “Governor” and he called her “First Lady.” He likes to show up at the fairgrounds and shake hands with citizens.

Hogan’s love for play acting as the ceremonial head of state got him into trouble when he was receiving chemotherapy for a very advanced and aggressive case of non-Hodgkin lymphoma during his first year in office. With a severely weakened immune system, he had to be warned by his personal oncologist to stop shaking hands at events. Hogan resisted this advice. “Hugs are like fuel to me,” he recounts. Later, at an event at Oriole Park, Orioles baseball great Adam Jones handed Hogan a pair of batting gloves, and he resumed shaking everyone’s hands.

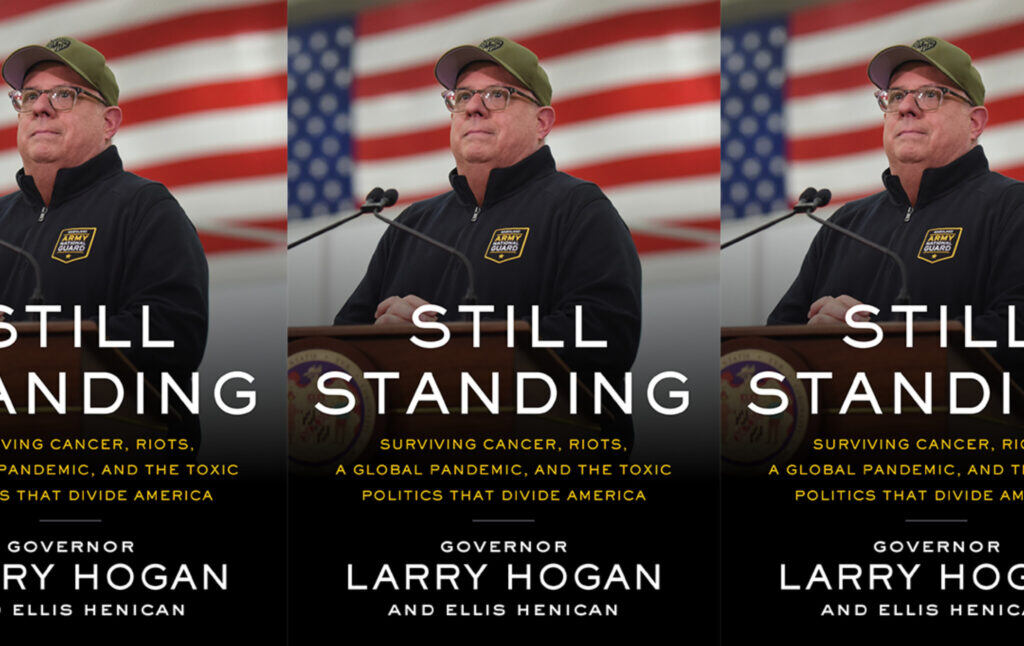

With the assistance of two world-class cancer specialists, Hogan survived his cancer scare in 2015. He went on to win reelection in 2018, a rare feat for a Republican holding statewide office in Maryland. In October 2019, he announced that he was in the process of writing a memoir that would be titled Still Standing: Surviving Cancer, Riots, and the Toxic Politics that Divide America. This would be his springboard to his future plans: term-limited from running for governor again, he could focus his attention on a future presidential bid, a challenging run for the U.S. Senate, or anything else he’d put his mind to.

But those plans would have to be put on hold. Just a few months later, in March 2020, the country was reeling from a global pandemic the likes of which it had not seen in a hundred years.

Hogan’s response to the crisis unfolding around him was to press on with not only the writing but also the publication of his memoir of triumph. He conceded to the changing times by adding an item to the list of things he would recount “Surviving” in the title of the book. The title was now: Still Standing: Surviving Cancer, Riots, a Global Pandemic, and the Toxic Politics that Divide America (emphasis mine).

What kind of person would publish a book boasting about “surviving” a pandemic that was not over—and was in fact killing more citizens every day? Even Andrew Cuomo’s October book, focusing on his “Lessons in Leadership” (while ignoring his lies about the scope of nursing home deaths in New York), is somehow less of a victory lap. Repugnant though it is, Cuomo doesn’t write as though the crisis is over. As Hogan’s book concludes he says, “In early May, the COVID numbers were finally beginning to plateau in Maryland.” The copies hit the shelves before the end of July 2020, at least in the bookstores that were still open. Needless to say, those COVID numbers would continue to rise.

The memoir’s bizarre release was just the latest episode in a career that has defied easy categorization. Most national news about Larry Hogan’s six-year tenure as governor of Maryland has centered around his unusual popularity for a Republican in a Democratic stronghold. Commentators both inside and outside the state have found this phenomenon puzzling and have tried to come up with various explanations.

To understand both his popularity and his hubris, it helps to understand a bit about Maryland.

The Middle Ground of Maryland

Maryland is a fundamentally white supremacist place. I choose all of those words carefully. In Hogan’s first inaugural address as governor, he spoke of a tradition dating back to the earliest European settlers as “those brave Marylanders who first came to this land seeking freedom and opportunity when they landed in St. Mary’s City in 1634. While the challenges facing us today are different, I know that the courage and the spirit of Marylanders is the same.” The many indigenous tribes, including the Algonquin, who already lived there, were not “Marylanders” in this sense. The Europeans who landed in North America started to create a society based on a hierarchy in which they were considered “white,” and where they could permanently enslave other persons who were not white. This didn’t happen at all once, but took decades of social engineering, with the structure of hierarchy and enslavement coming first and the concept of “race” afterwards.

When many Americans think of slavery, they probably go first to the most visceral horrors: torture, rape, family separation. But it is also the most extreme form of a common type of economic exploitation: the theft of the results of your labor. Frederick Douglass, enslaved in Baltimore in the 1830s, worked for wages at a shipyard, but had to hand over “every cent” of the wages to his owner, Hugh Auld, every Saturday night. As Douglass later wrote: “He did not earn it; he had no hand in earning it; why, then, should he have it?”

Imagine this theft, every Saturday, for your entire life. Douglass’ labor, from the day he was born until the day he escaped Maryland, turned into capital that, by the laws of the time, accrued to the Auld family and was never returned to him. Douglass’ own body was itself a financial asset, subject to being bought and sold, taxed and mortgaged. This financial asset was created/born in 1818 from the rape of his mother, Harriet Bailey, by an unknown white man (possibly their owner at the time, Aaron Anthony). Imagine how quickly capital can grow if a financial asset can literally give birth to more capital!

Even though Douglass and Auld are now long dead, all the capital created by enslavement never disappeared. It’s still somewhere out there in the world. And Douglass is only one of the most famous examples of all the millions of workers who were forced to help grow it. Most of these workers never escaped their captivity. The theft of all these lifetimes was the basis of an entire society. And the wealth it created then still exists today, grown by compound interest over centuries.

Slavery ended in Maryland in 1864. The wealth and power it had built stayed put. Because the state never seceded, it was not subject to post-Civil War Reconstruction policies that were implemented to varying degrees in the former Confederate states. Instead, Maryland’s legislature invented broad new criminal laws, applied only to Black citizens, to compel the labor of the former slaves for their former masters. The state’s police departments are still tied to this dynamic, a century and a half later. The poet and sociologist Eve Ewing has referred to the institution of policing as “a means of violently controlling working persons’ right to economic freedom… The need to attack workers in the name of private interests is historically intertwined, like a double helix, with the need to control, limit, and sanction Black autonomy.” In ways new and old, the theft of the fruits of the labor of black workers continued in Maryland. A system of Jim Crow, enforced by state violence and terrorism, persisted into the 1950s.

This is certainly an unpleasant history to look back upon. To make matters worse, the effects of these policies did not stay stuck in the past—in many ways, the economic relations of the previous centuries are still with us. Formally ending Jim Crow, while a necessary step, only froze in place the economic power relations built by the centuries of enslavement and plunder.

This is the economic order into which Larry Hogan was born and raised, in the suburbs outside Washington, D.C. He also grew up intimately familiar with the political dynamics of Maryland.

Maryland: A One-Party State

Maryland has been the state most consistently loyal to the Democratic Party, ahead of Massachusetts and Rhode Island (which were dominated by Republicans at the state and federal levels from the mid-19th century until 1928). Maryland was Democratic along with the “Solid South” (from the end of Reconstruction until the Civil Rights Acts of the 1960s) and then stayed Democratic, both in its presidential votes and at the state level, as the rest of the south switched. Generally, you can explain this phenomenon by looking at the way white supremacy continued to flourish within the Maryland Democratic Party. One-party dominance encourages greater ideological variations within that party, and spurs real battles over who gets to govern in the party’s primaries. It also lowers the stakes of electing a Republican as governor once in a while.

Hogan’s spiritual predecessor was Spiro Agnew, Nixon’s first vice president. Agnew rose to power in Democrat-dominated Baltimore County and then became governor of Maryland by taking advantage of Democratic infighting. As executive of the former in 1963, journalist and author Antero Pietila writes, Agnew “pledged to steer a middle course between ‘the hatreds of segregationist dogma on the one hand and the unreasonable ultimatums of some power-crazed integrationist leaders on the other.’” In Maryland at the time, this sort of statement qualified you as a moderate. Decades later, Hogan would attempt to take a similar path.

For the entirety of Hogan’s tenure, Democrats have held veto-proof majorities in both houses of the legislature. Having to pass the laws with a veto-proof majority instead of a simple majority helps rein in the ambitions of the progressives in the state legislature and preserve the status quo. What this amounts to is actively perpetuating, as much as possible, the world created by the government of the past. Maintaining the status quo requires stern enforcement, backed by state violence. Abolitionist scholars like Angela Davis have documented over the past few decades how police and prisons have filled in for declining, defunded social institutions.

This enforcement inflicts a lot of misery on its victims. A report in 2019 found that Maryland has the highest rate of incarceration of Black people (relative to its population) of any state in the country, ahead of Mississippi: “More than 70% of Maryland’s prison population was black in 2018, compared with 31% of the state population.”

This has been a bipartisan project. The most recent Democratic governor of Maryland, Martin O’Malley, rode the politics of mass incarceration to two terms as Baltimore’s mayor (in 2005, he oversaw nearly 109,000 arrests in a city of 636,000) and another two as governor. When Hogan became governor, he was happy to follow this blueprint.

Pitting Baltimore against the rest of the state proved to be a recipe for success. Voters who found this appealing didn’t necessarily want “small government” at the federal level, since the proximity to power is one of the reasons for the region’s affluence (Maryland boasts five of the 25 wealthiest counties in the United States), but they did want a small state government when it came to their tax dollars going to help Baltimore. In Still Standing, Hogan points to his ability to avoid getting “pulled into hot-button social issue debates” as key to his 2014 victory, along with voter antipathy to their perception of being overtaxed under the term-limited O’Malley.

Lacking the ability to put forward any legislative agenda thanks to the veto-proof Democratic majorities, Hogan instead sought to maximize his personal popularity. Focusing relentlessly on publicity, he succeeded at staying popular and at winning reelection. In this effort he had willing partners in the largely sycophantic local media. This reflects less his great media savvy than the common material interests of the region’s surviving media companies. The Tribune conglomerate owned the Baltimore Sun—once a publisher of classifieds for slave auctions and runaways, and an uncritical reporter of local lynchings—and also bought the Baltimore City Paper, only to shut it down. Jeff Bezos owns the Washington Post, and the Trump-propagandist network Sinclair owns much of the local TV and radio. The constituencies to which Hogan is openly hostile (particularly teachers unions and the people of Baltimore) were also disliked by enough Democratic voters for him to be successful.

The biggest test of Hogan’s first term (aside from his personal health problems) would happen only a few months after he was sworn in. But he was able to turn it into more good P.R. by continuing to exploit his constituency’s views of Baltimore.

“Surviving Riots”: Freddie and Larry

Larry Hogan and Freddie Gray were born and raised within 40 miles of one another, but in two vastly different situations. Their lives would converge unexpectedly in 2015.

Hogan was born in 1956 in Washington, D.C., not long after Brown v. Board of Education started the process of attempting to desegregate the public schools in the United States by order of the federal courts. His parents quickly moved, as many white families did, from the city to nearby suburbs—in their case, Prince George’s County, Maryland. P.G., as it is known, is now majority-Black, and has been since the 1990s. Hogan euphemizes these demographic changes in Chapter 1: “Making Larry”: “Our town was solid but a little rough around the edges. It’s far rougher today.” Of his upbringing, he says, “We had a nice, suburban family life. We weren’t rich, but we were happy and comfortable. I felt like nothing really bad was going to happen to me. An upbringing like that can send a kid into the world with a sense of belonging and the self-assuredness to think he can achieve anything.” Having a father who served in the U.S. Congress—and later as the county executive—probably didn’t hurt either.

Gray was born in 1989 in Baltimore. During his early childhood, he and his two sisters lived in a West Baltimore house that had peeling paint in every room, as his mother, Gloria Darden, later described it. This paint contained lead that would poison all three of her children. Lead poisoning, as the Post detailed in a study of Gray’s life, is considered to “diminish cognitive function, increase aggression and ultimately exacerbate the cycle of poverty that is already exceedingly difficult to break.” This completely avoidable result was inflicted upon tens of thousands of children in Baltimore.

In 2015, a few months after Larry Hogan was sworn in as governor, Freddie Gray was dead at the age of 25. He had been arrested by the Baltimore Police and died of injuries sustained in their custody, including a severed spinal cord.

Hogan writes callously about the dead young man in Still Standing. Employing the “no angel” racist trope, he says, “There is no point in confusing Freddie Gray with a singer in the church choir, the way some in the media did. He was a Crips gang-connected, street-level drug dealer with a long criminal rap sheet, well known to the Baltimore City police.”

Whether this statement about Gray’s supposed Crips affiliation is true or not (and it appears to be bogus), one wonders what Larry Hogan would have become had he been born in Baltimore and poisoned as a baby, lived in poverty in dilapidated housing, and attended under-resourced schools. Instead of growing up with a father who had once worked in law enforcement (for the FBI), and a belief that the police were there to serve him and help keep him safe, perhaps Hogan would have been frequently harassed by police officers. Would he still have set out to make his mark on the world with a sense of belonging and self-assuredness?

In Still Standing, Hogan goes on to proudly recount his bold actions to bring in the National Guard to put down the “riots” in the city after Gray’s death. He seems to take special delight in describing himself bossing around Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake and being curt with President Obama. By calling in the Guard, Hogan was following Agnew’s playbook from the 1968 unrest after the murder of Martin Luther King, Jr. Locals prefer to refer to the April 2015 events as the “Uprising,” but either way, the violence was started by the police, after they herded thousands of students into one transit station on the day of Gray’s funeral and refused to allow them to leave. Hogan writes that during the chaos, “organized gangs were backing up trucks to a rear door, cleaning out the pharmacy of all manner of drugs.” At least some of these gang members turned out to be members of one of the city’s most notorious gangs, the Baltimore Police Department.

When Hogan speaks as he does about Freddie Gray and the uprising in Still Standing, it’s clear that he is not ashamed of himself. More troubling, though, is that he also has (justified) confidence that his constituency will not be repulsed by his words. They enjoyed seeing Baltimore put back in its place by a military occupation.

Of efforts to do anything to address the living conditions in Baltimore, Hogan has much less to say. He pledges to the president of the local NAACP chapter, “We’re going to address the underlying causes.” Whatever he may have done in the six years since this pledge, he doesn’t concern himself with it in his memoir.

COVID in Maryland

After the Baltimore uprising, Hogan went back to his lazy, poll-driven style of government. It worked, at least to a certain extent—he knew his place. Trump laid off Hogan because he was a popular Republican in a blue state like Maryland (“Maybe Trump really did respect my high approval ratings,” Hogan marvels), while Hogan didn’t challenge Trump—either in public life or in the contest for the 2020 Republican nomination—because he understood how to pander to his base.

Hogan would likely have finished his second term in this posture, but COVID got in the way.

Hogan’s handling of the pandemic in Maryland has reflected the personal successes and public failures of his overall tenure as governor. Every effect of the crisis has been visited with fierceness on minorities and the poor, and the government’s response has been to prioritize the goals of the whiter, wealthier, and more powerful, but in such a way that Hogan remains popular in the opinion polls. A sufficient number of voters in the state are content with things as they are. The miserable, the desperate, and (obviously) the dead do not factor into the polls enough for anyone in the administration to take notice.

Once the vaccines arrived, their early rollout in Maryland was slow and clumsy. Poor planning led the government to scramble and contract out some of the work. A Bloomberg report in late December found that of all states, Maryland had administered the lowest amount of its allocation to date, just 10.9 percent.

The state set up mass vaccination sites in Baltimore at the convention center (later at the Ravens football stadium) and in P.G. at the Six Flags amusement park. In Baltimore, an early March pie chart breakdown showed that only 37.9 percent of the vaccines were going to residents of the city, with a majority going to residents of other counties, and even some to residents of other states. (P.G. had been even worse, with 80 percent-plus of Six Flags doses going to non-P.G. residents.) A chaotic distribution system that puts all the responsibility on each citizen to make their own appointment and provide their own personal transportation to the vaccine site, then possibly take a few hours to make their way through the line, is naturally going to favor the kinds of individuals who have the time and resources to do all of these things.

Lawrence Brown, who has recently written a book about the neglected, majority-Black “black butterfly” sections of East and West Baltimore, referred to this as “vaccine apartheid.” Late in February, white Marylanders had received four times the rate of vaccinations as Black Marylanders had, with state officials seemingly puzzled by it all, with no ideas for how to better serve everyone. Hogan could only toss out that it must be the fault of Black people themselves, who supposedly are superstitious and more hesitant to take the vaccine; that is, not anything he could be held responsible for. (This, obviously, has no factual basis.) Hogan had also hired Trump’s CDC director, Robert Redfield, who promptly attracted controversy over his conspiratorial speculation that the virus had escaped from a Chinese lab.

The pandemic had revealed interlocking crises of unemployment, lack of healthcare, food insecurity, and evictions. Unemployed workers were stuck waiting for months before receiving the payments they were entitled to. Overdose deaths were on the rise. But within Hogan’s coalition—professionals who could afford to stay home—the crisis was a much less life-threatening matter. With their desire to send kids back to schools and to return to in-person dining at restaurants (and the business owners who wanted their patrons back), the priority was reopening public places as quickly as possible, even as the spread continued in schools and workplaces and people kept suffering and dying.

State restrictions have been chaotically ordered, then rolled back, then reordered as cases go back up, repeatedly over the past 13 months. Local officials (not just in Baltimore) have repeatedly been left out of the loop, learning about the new orders at Hogan’s press conferences. The state’s Democrats, for their part, were mostly content to let Hogan own the issue and stay out of the way of either the praise or blame. Having adjourned from their 2020 legislative session early as the crisis was starting to unfold in March, they declined to call a special session and waited until their regularly scheduled session 10 months later in January 2021. Therefore no state COVID relief bill was passed until mid-February 2021, as thousands of citizens languished.

Of course, all this is what has happened since Still Standing came out. That book ends in May 2020. Hogan’s supposed crowning accomplishment in this section of the book is his diplomatic mission to purchase test kits from South Korea for $9.5 million, pulling a fast one under the nose of the Trump administration. The P.R. battle won, the world moved on, barely pausing to note that these test kits were not usable.

By the end of the year, 5,727 Marylanders had died of COVID. (These deaths were largely in Baltimore and P.G. At least 18 were prisoners.) The true numbers may be higher, as some deaths were undiagnosed. There were more than 277,000 confirmed cases. In the months since, the numbers have risen to over 418,000 cases and more than 8,300 deaths. Each surviving case is someone who may suffer serious long-term health effects. Each death may be a person who died alone, with their loved one watching on an iPad.

The Sun profiled some of the victims in late December in a kind of mass obituary. A few days later, Hogan announced an executive order that Santa Claus was exempt from COVID travel restrictions.

That might be the single best encapsulation of Hogan’s reign as governor. On the surface, it may seem amusing and harmless. But it hints at a worldview that refuses to accept the realities of modern life, and will go to great lengths to deny what is obviously true. Hogan offers a false and impossible compromise between an antidemocratic Trump-led right wing the “good old days” and a liberated future—one that looks suspiciously similar to the former, albeit with a fresh coat of paint. But like the walls of Freddie Gray’s childhood home, this is poisonous.

One more incident is worth mentioning here. After Hogan won his reelection campaign in 2018, he danced on stage with a surfboard at the Inaugural Gala, symbolizing his ride atop the “blue wave.” After speaking to the crowd, he was played off the stage by the ’70s tune “Stuck in the Middle With You.” It made me wonder:

How much longer will we be stuck?