Before I tell you why I stopped running, let me first explain why I ran. Long before COVID-19 began killing people in the South Bronx at twice the rate of New York City’s four other boroughs, and long before we learned that a separation of six feet between strangers could slow the spread of the virus, I was busy social distancing from a different kind of plague. I left the South Bronx in 2003, at the age of 18. Hungry to taste the riches of American opportunity, I headed north to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to study how to construct bridges, assemble devices, and perform all that engineers do, or so I was told by those who better understood what engineering actually meant. As a high schooler, I wanted to make my corner of the hood better. So, armed with a penchant for math and physics, and a love for art, I heeded the advice of the guidance counselor who told me that an education at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology was the opportunity of a lifetime, a chance to learn how to build.

My immigrant parents were exceedingly proud, but were perhaps most excited that I had, for the second time in my life, gained admission into an elite school tuition-free. I had spent the previous four years at a private Jesuit high school where a multimillion-dollar endowment had purchased my family’s first desktop computer. Accustomed to solo travel by a daily subway commute between my modest neighborhood and my high school in the Upper East Side of Manhattan, I felt at ease as I bought a $15 ticket from Fung Wah Bus, and settled into the four-hour journey from Canal Street, up through Connecticut on I-84 East, all the way to Boston’s Chinatown, where I entered a different subway station—the T, locals called it—that ushered me to the first phase of my university education.

Once at MIT, I found that the more distance I put between myself and home, the more I struggled to forget what I did not want to remember. I sat in the front row in multivariable calculus to forget that I was still one of a handful of Black students in the classroom. I studied physics in bedrooms and chemistry on dorm sofas to forget about being carded by campus security in the student center after dark. I chased internships in Boston and Washington, D.C. to forget that none of the engineering companies at the freshman career fair had corporate offices near the Bronx. I studied abroad in South Africa and Brazil and France to forget my very first exposure to global poverty: the smell of urine on a homeless man’s soiled pants as we rode the New York subway together to high school each Tuesday morning. I trained myself to forget the bitter taste of racial injustice in America and focus on the sweet promise of equal opportunity.

On a humid August day, four years after leaving home, I moved into the basement room of a three-story row house near Johns Hopkins University. Convinced my MIT education was not enough, I was there to enter a graduate program in environmental engineering. No longer content with building bridges and assembling devices in my home neighborhood, I had driven past New York City in a used Honda Civic and stopped only once I reached Baltimore. Two roommates shared the house with me: my college fraternity brother from Murfreesboro, Tennessee, a second-year biomedical graduate student at the time, and a tall medical student from Battle Creek, Michigan, who later joined the same historically Black fraternity.

The three of us drove to IKEA to purchase new furniture using my fellowship money. Along the way, we passed abandoned buildings, vacant lots, and street corners decorated with unemployed Black men. I felt a quiver in my stomach as I turned my attention to the Blackberry clutched tightly in my palm. And still, I fell in love with the self-proclaimed “Greatest City in America.” Baltimore felt to me then like a place bursting with potential—the sound of urban development near Butchers Hill; the history of America’s pastime in Camden Yards; the dance of cobblestone along Fells Point; the smell of vibrant eateries throughout the Inner Harbor. Perhaps the city embodied America’s great land of opportunity because it offered my roommates and me so many opportunities to forget the individual misfortunes associated with our homes, similar even as we hailed from different regions of the country—that is, if we were willing to look away from Baltimore’s racial segregation and concentrated poverty so as not to see ourselves in its Black citizenry. Either way, social distancing had not only given me new purpose, but also a new vision of city life. I ignored the city’s troubles and chose to forget who my friends and I had become: modern incarnations of Ralph Ellison’s invisible man hidden behind Frantz Fanon’s white mask. As Fanon described: “Sometimes people hold a core belief that is very strong. When they are presented with evidence that works against that belief, the new evidence cannot be accepted.” I knew that I was Black, but I believed my ambition set me apart.

So, rather than investigate the engineering failures that had robbed much of Baltimore’s Black population of safe housing and well-planned neighborhoods, or explore how to rebuild abandoned lots that had been dismantled by violent protests during the Civil Rights era, I studied the environmental challenges posed by the thickets and deep ravines of South Africa for subsistence farmers. I visited rural villages in KwaZulu-Natal, dug trenches and laid PVC pipes for sustainable irrigation systems, and wrote a 70-page thesis about environmental security and conflict abroad. It felt good to help, but as we studied maps of South Africa on the projector screen in class, I wondered if we were also learning how to forget the geography of poverty outside our window: the unemployed, underemployed, and low-wage workers of Baltimore whom we’d fashioned into abstractions of poverty in America’s so-called “land of the free.” Between my department’s enchantment with global humanitarian conquest and my own pursuit of academic achievement, it was becoming harder for me to see the commonalities between the economic struggles my immigrant parents had endured in New York—my mom as a nurse in the Bronx, my late father as a bus driver in Queens—the struggles of Black health care workers and bus drivers in Baltimore. Blocking out memories of racial injustice had enabled me to focus on the opportunities before me, a lesson I had learned at MIT, while also pushing my sights further from home. I chose to forget the joy of dancing under fire hydrant showers in Bronx summers as a kid, and looked toward becoming someone different, someone whom I believed was better.

My socially isolated position in academia caused me to interpret the state of racism in the United States in almost religious terms. I saw the legacy of America’s white supremacy, as manifested through social norms, laws, and policies, as a kind of original sin, a fallen, unethical state of nature. My personal efforts—working twice as hard as my peers, never settling for the status quo, forgetting my humble beginnings—became my salvation. I epitomized resilience amidst pervasive economic vulnerability; saw myself as sheer will incarnate, determined to realize hood dreams. The latter were at bottom a South Bronx-forged version of the American Dream, passed down from my Dominica-born grandmother. It was she who had instructed me as a child that education would save me. I clung onto her words, convinced that my story made me “exceptional” in the meritocratic sense, rather than a lucky exception to the senseless travesty of American capitalism. Raised as a Christian, I prayed each night for courage. But my faith was mostly in the success of hard work alone. After all, prestigious institution after prestigious institution had validated my theory, and would again when Harvard Law admitted me in 2009. So, I swallowed the wine of elitism and genuflected before altars of opportunity, left behind the sins of A Tribe Called Quest and pledged allegiance to the gospel of Coldplay—fighting stereotypes with one breath and embracing them in the next. I returned less and less to the South Bronx, unwittingly morphing into what James Baldwin called the “stranger in the village.”

In his essay by the same name, Baldwin reflects on his experiences as a Black American visitor to Leukerbad, Switzerland, describing the United States’ social and political efforts to make its Black citizens “strangers” in the American village. Baldwin regarded the existence of inhumane Black ghettos as a symptom of America’s unwillingness to acknowledge the threads of white supremacy woven into “the general social fabric” of its democracy, and of its stubborn habit of looking away to avoid looking within. To Baldwin, justifying Black urban slums with culture represented a vain attempt to recover “European innocence” by making “an abstraction of the Negro.” By willfully ignoring the relationship between economic inequality and racial discrimination against Black Americans, the United States had become “trapped in history.”

It wasn’t until law school that I finally realized history had become trapped in me. Intramural basketball had been a constant source of reprieve since my arrival at Harvard, a place where a diverse coalition of men and women could leave political differences at the gym door and bond over a shared love of sweat, grit, and ambition. I had grown to love the game at a young age, after my father hammered a fiberglass backboard and orange rim to the porch railing above the driveway behind our row house. Working on my jump shot for hours on Saturday mornings became a kind of ritual for me. I must have been pushing myself too hard for one too many games at Harvard’s gym, when an unexpected collision landed me on a stiff stretcher in the back of an ambulance. My torn anterior cruciate ligament would demand my first major surgery since getting my tonsils removed as a toddler. But more than that, the painful tear forced me to slow down. Confined to crutches, I relied on painkillers and friends to keep up with classwork.

Before my injury, I had started watching episodes of The Wire—the HBO prestige series set in Baltimore—to prepare for a seminar called Race and Justice: The Wire, taught by legendary law professor Charles Ogletree. Laid up in bed with a swollen knee and nothing else to do, I binged all five seasons in what felt like a matter of days. It was then I saw, really saw, for the first time a side of the city isolated from the privileges that I had enjoyed at Hopkins. It was not the sight of poverty or drug dealing or even racist policing that captured my attention. I had witnessed all of that before. The police had killed Amadou Diallo three blocks from my doorstep. A childhood playmate of mine had joined the Latin Kings in high school. Rather, it was the sudden realization that I had walked past real-life versions of the characters in The Wire while studying in Baltimore. In my quest to escape the Bronx, I had never once stopped to learn their story or dignify their struggle.

My obsession with America’s romantic dream and attempt to escape my deepest fears—fear of failure; fear of loneliness; fear of not being enough—had morphed my neighbors in Baltimore into surrogate Black bodies, sources of self-regard to give my life meaning, to render a safe space outside of the ghetto to experience the frailty of my human condition. I had learned to manipulate tropes of blackness to make sense of America’s unboundedness, to justify my craving for frontier, to contemplate, in the words of Toni Morrison, “the terrors of human freedom.” As I strived for more to forget the ubiquity of life with less, I became a fugitive in a brave new world, running from who I was to become the kind of man America has long celebrated—a man of property.

Professor Ogletree’s seminar had unveiled a hood buried beneath the thick veil of frustration and despair that lined the streets I had come to know so well, streets that divided academic prestige from concentrated poverty. It was the show’s iconic characters, “Detective Jimmy McNulty” (Dominic West) and “Kima Greggs” (Sonja Sohn), who would teach me about the political and legal dimensions of policing in Black neighborhoods. From “Bubbles” (Andre Royo), the recovering heroin addict who roamed the streets of Baltimore in search of customers to purchase white t-shirts from his shopping cart, I learned about the difficulties of unemployment for people deprived of the golden ticket of academic pedigree. From drug kingpin “Russell ‘Stringer’ Bell” (Idris Elba) and youth drug-seller and auto thief “Donut” (Nathan Corbett), I grasped the challenges of educational uplift for folks weighed down by the anchor of social instability.

Unlike the neutrality and cold detachment that characterized Harvard’s mandatory first-year Criminal Law course, Professor Ogletree’s (optional) seminar for second and third year law students invited us to invest ourselves in the fates of the city’s stakeholders, to see them as people rather than pawns in a game of indiscriminate litigation—not to promote a hidden political agenda, but to develop within us a greater self-awareness and moral critique of American democracy. After watching “Sentencing” (Season 1, Episode 13), we’d debated the futility of the war on crime, given that arresting one group of drug dealers had merely permitted another gang to rule the streets. And after “Hamsterdam” (Season 3, Episode 4), in which the police chief establishes drugs-tolerance “free zones” in dilapidated areas of Baltimore, we’d discussed at length the shortcomings of the war on drugs and the prospect of alternate solutions. Discussing the contours of racist policing and mass incarceration amidst the complexities of a drug culture that, for some, serves merely as a soothing balm to allay the aches of poverty, we’d concluded that our legal system was not neutral, and that some outbreaks of community rage were more than justified.

Only then did I realize that Baldwin was right. I had become a devotee of the religion of racial performance, a faithful participant in the rituals of white supremacy and capitalism, which together established the rungs of social hierarchy that for so long I had desperately sought to climb. I was a co-conspirator in the hypocrisy of America. Daily, I had worked to prove to my white peers that I, a Black man in America, belonged at MIT and Johns Hopkins and Harvard, just as I had worked to prove to my Black peers that I belonged on the basketball court. I’d learned to bury my personal American history: my childhood subway rides from the South Bronx to the Upper East Side; the economic struggles that had propelled my grandparents from the islands of the Caribbean to the tenements of New York City; the stories of countless Black families I met growing up, who stand as the legatees of America’s Great Migration. All of it was trapped in me, buried under the weight of colorblindness and exceptionalism, mingled with a stubborn conviction that forgetting the ugly truth about economic inequality was necessary to forge a pathway toward freedom.

My secondhand exposure to Baltimore’s underbelly fostered in me, in the words of the feminist scholar bell hooks, an “education as the practice of freedom.” It also helped me understand the protests that ignited the city’s streets after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in April 1968, and the hauntingly similar protests that exploded after the tragic killing of Freddie Gray at the hands of Baltimore police officers in April 2015, and the global protests that left American cities smoldering in the summer of 2020 at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. These uprisings were not merely byproducts of the social isolation of Black communities, beset with racially biased policing and unmitigated de facto racial segregation. They also stemmed from the economic isolation of the poor into American nightmares haunted by underpaid jobs, underfunded schools, under resourced healthcare facilities, unclean neighborhoods and parks—all of which have existed since the earliest colonists dreamed of revolution. We have simply been trained to forget.

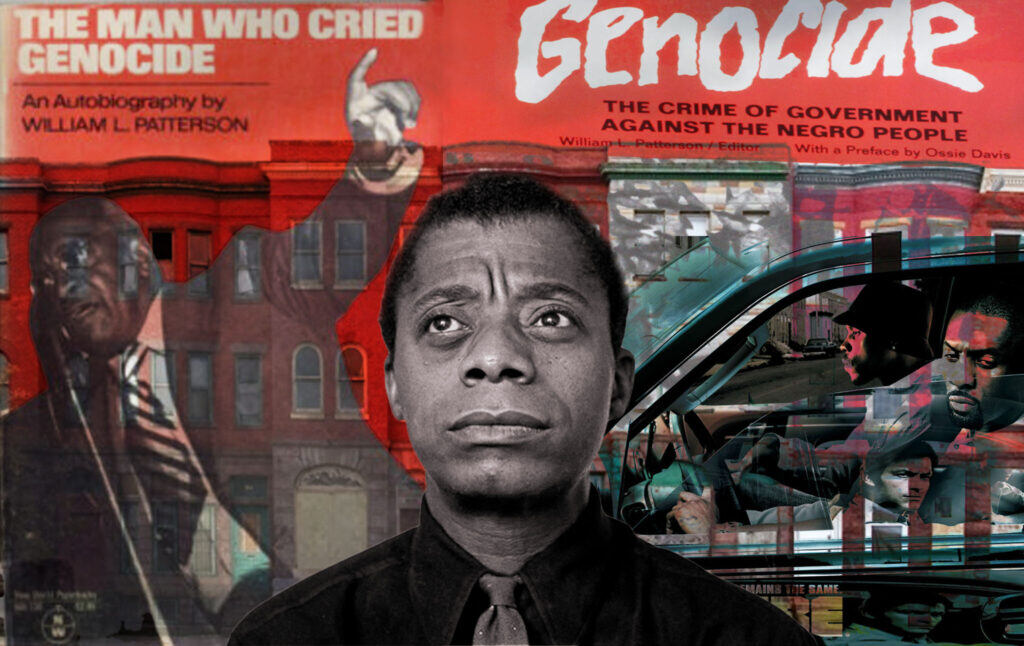

Long before protesters began chanting “Black Lives Matter” in the streets of Ferguson and Baltimore, long before Donald Trump turned America’s bully pulpit into a stage for bullying, long before the novel coronavirus began decimating Black neighborhoods across America, a man named William L. Patterson was advocating for Black lives before a global audience at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris. An influential activist and leader in the American Communist Party, Patterson must have looked odd on that December day in 1951, as he delivered his petition in France in a foreign tongue to the United Nations Committee on Human Rights. “We Charge Genocide,” the Black man declared in a voice that I imagine sounded like the battle cry of a soldier on the front line, nervous yet defiant, hopeful for the war to end.

Drafted by the Civil Rights Congress, and signed by leading civil rights activists of the day, including W.E.B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson and Claudia Jones, “We Charge Genocide: The Crime of Government Against the Negro People” boldly declared that the U.S. government had violated international human rights law by sanctioning “persistent, constant, widespread, [and] institutionalized” genocide of African Americans. To demonstrate the U.S. government’s complicity and responsibility in efforts to destroy Black America “in whole or in part,” as defined by the U.N. Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, the report documented the police killings and lynching by mobs of 152 Black people between 1945 and 1951—a sliver of America’s brutal episodes of racial violence during that era. Patterson’s petition also unveiled the crippling impact of isolating millions in “inhumane Black ghettos” marked by substandard housing, education, jobs, and health care.

More than civil rights, Patterson called for the United States to be held accountable and condemned by the nations of the world for violating the human rights of Black Americans through “consistent, conscious, unified policies of every branch of government.” Although the petition was well received in Europe, news media in the U.S. suppressed and derided it as “Communist propaganda.” Meanwhile, politicians worked to erase Patterson’s voice from collective memory. Eleanor Roosevelt, the former First Lady and then-head of the U.N. Human Rights Commission, called the charge “ridiculous,” even though just three years earlier she’d led the charge on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which made clear that racial discrimination must not deprive any human of their rights and freedoms. Upon returning home, the government seized Patterson’s passport. Perhaps most ironic, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, whose research on police brutality and lynching had substantiated many of the claims in the petition, caved to pressure from the State Department and condemned “We Charge Genocide” as “a gross and subversive conspiracy.” From that point forward, the U.S. government worked hard to maintain the widespread illusion that human rights violations only occur in faraway countries like Rwanda and Sudan. I was never taught about William Patterson or We Charge Genocide in my 20-plus years of schooling.

Silencing Patterson and his human rights petition was a squandered opportunity to reconsider the concept of personhood in the Leviathan. While the rule of law and social contract have the power of guaranteeing every American liberty, this power is far from fully realized because we continue to view ourselves as exceptional. Our fixed obsession with the idea that the United States already enjoys unparalleled heights of liberty and opportunity has caused us to see prescriptions for liberation as threats to America’s (perceived) greatness. We justify inequality as a sanctified opportunity for the rich to serve the needs of the poor. Once fused with the language of racism, such old-fashioned beliefs stifle our collective imagination for democratic possibility, while rationalizing our association of concepts like welfare with the alleged laziness of Black people and the assumed illegitimacy of immigrants.

Far more than a tool to condemn, the language of human rights pushes us to consider the primary role of dignity in assessing the effects of policy on human lives. For example, while the concept of fair housing focuses on equal protection against discrimination when one is exercising liberty to rent or buy a home, the human right to adequate housing focuses on the indignity of being deprived of a standard of living adequate for health and well-being. The human rights frame reveals that one can experience equality under the law, by securing freedom from the discrimination of others—what some view as the defining achievement of the Fair Housing Act—yet simultaneously experience unfreedom under the law, by remaining subject to systemic racism and the mythologies of whiteness—what others view as the ongoing injustices that inspired the Black Lives Matter movement. Put another way, human dignity demands not only the inclusion of subordinated citizens into the marketplace, but also the recognition of dominated, yet invisible, citizens within the marketplace. This recognition is not only foundational to the development of self-awareness that facilitates the pursuit of well-being. It is also crucial to a thriving democracy.

The future of American democracy then demands a radical reconstruction of rights that bears witness to the freedom dreams of oppressed peoples, beyond coordinated public health measures and short-term stimulus plans in response to COVID-19; beyond social distancing rules to survive the plague; beyond white guilt, corporate committees on diversity and inclusion, and anti-racist trainings to cleanse us of racist beliefs and implicit biases; even beyond critical race theory primers in the ivory towers of academia. Radical reconstruction calls for moral reckoning as a nation that transcends healings of the mind. Rather, the task at hand demands an exorcism of the specter of exceptionalism that claims that America is already great, that American citizens do not deserve rights to free higher education, free national health care, adequate housing, living wage jobs, and other redistributive, class-based reforms to dismantle the wealthy’s stranglehold on the poor. To bring it about, we must rip to shreds our limited conception of what Hannah Arendt called the human condition; we need the kind of collision that led to a spiritual breaking in me on the basketball courts of Harvard Law. But breaking, I have learned, is only the beginning of healing. Some lessons are hard to remember, and some memories are easier to keep forgetting, again and again.

Although my injury, my absorption of The Wire, and the conversations in my seminar had unsettled my assumptions about the city I had called home for two years, it did not immediately alter my own plans. I graduated law school in 2012 with an offer from a white-shoe law firm that would pay me more money as a know-nothing associate than both of my parents had ever amassed in one year. For some folks, myself included, the fiction of money has always felt like the best way to buy real freedom in America. Even if the game ends up being rigged, at least you could finally afford Air Jordan 11 Space Jams and a ticket to the NBA finals. And so, hood dreams lulled me back.

This is how I found myself sitting at a mahogany desk in the nation’s capital, a few months out of law school—sharp in my custom tailored suit, fit for a prestigious firm a stone’s throw from the White House—as the chants of protestors pierced through my window like a bolt of lightning: Black Lives Matter. Black Lives Matter. Black. Lives. Matter. The words wafted from Pennsylvania Avenue up to my office and lingered, stifling me with an unease not dissimilar to that I imagine the U.N. delegates felt in Paris as Patterson declared: “We Charge Genocide.” It struck me in that moment, fluorescent light glittering upon my shined leather brogues, that loss is an essential condition of capitalist accumulation in America: loss of our individual stories of freedom struggle; loss of our individual memories of racialized subjugation and human atrocity; loss of our spirit of resistance; and perhaps most terrible, loss of ourselves.

I left the firm on Pennsylvania Avenue after two short years. The last day felt like the final minutes of a sleep paralysis where I could see my body for what it truly was, but struggled to understand the power of my bondage. I shook myself loose of a six-figure salary and headed to a non-profit civil rights advocacy organization, then on to legal academia, intent on searching for more among those with less, and on finally confronting my ghosts. Yet, I did not march in the streets of Washington, D.C. after the police killings of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Rayshard Brooks. This time, a part of me felt numbed by the risks of the novel coronavirus. I am the father to two Black sons who I hope to one day teach the game of basketball. But I must confess, I also found myself wondering if my fear of being killed by the police, and consequently my absence from those protests, could be compensated for—or forgiven—by being one of a handful of Black male law professors in the United States doing anti-racist teaching, community-based legal advocacy, mentoring of diverse law students, and writing on racial justice, human rights, and law reform. Was I already doing enough? Was I finally enough?

As James Baldwin contends in his 1951 essay, “Many Thousands Gone,” “The man does not remember the hand that struck him, the darkness that frightened him as a child; nevertheless the hand and the darkness remain with him, indivisible from himself forever, part of the passion that drives him wherever he thinks to take flight.” Though no longer running from my history, I was and still am afraid of what we, as a country, might become if we remain trapped doing what we have always done. But I find hope in human rights discourse and its insistence on dignity as integral to any meaningful conception of freedom. I see it as a means to unearth the darkness of American history we each carry within. A laboratory for the collective and ongoing project of re-imagining legal subjectivity and redefining state responsibility. Not only can the language of human rights help us craft a new vision of American democracy, it can serve as a tool of remembrance to reckon with what America has always been. I am reminded here of Professor Eddie Glaude Jr., who declares in his book, Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own, “Americans must walk through the ruins, toward the terror and fear, and lay bare the trauma that we all carry with us.”

In this age of political uncertainty and social unrest, shaped by the logic of racial capitalism and the resilience of white supremacy, remembering the clarion call for human rights of yesterday can guide us through the ruins of today.

Perhaps to begin again, we must first stop running, and remember.