Nonprofit Workers, Unionize!

Until you can pay your rent with good intentions, you need the protection of a union contract.

It’s been a tough half-century for U.S. labor unions, but seeds of hope are blossoming across the country in unexpected places. Even in the nonprofit sector, workers are unionizing— signaling that the modern-day labor movement is alive and kicking.

Approximately 40 years ago, 20 percent of the U.S. workforce was unionized; today, it’s 10 percent. Despite this downturn, a recent Gallup Poll indicates 65 percent of Americans approve of labor unions, the highest level of support since 2003. In recent years, but especially since the onset of COVID-19, the U.S. has seen a resurgence of labor activism. Increasingly, employees are harnessing their power as workers (despite contrary efforts like California’s Proposition 22). In the past five years, the NewsGuild and Writers Guild of America, East, have unionized 90 newsrooms and over 5,000 journalists; according to Harvard Business Review, “the number of unionized workers in internet publishing has risen 20-fold since 2010.” Earlier this year, Google employees announced they had formed the Alphabet Workers Union, indicating a shift toward organizing in the tech industry. During the pandemic, people have also been leveraging their labor to effect change for others. Last March, General Electric factory workers who normally produced jet engines walked off the job, demanding to make much-needed ventilators instead. In August 2020, the Milwaukee Bucks staged a wildcat strike after the police shooting of Jacob Blake, which prompted teams and players throughout the sports world to follow suit.

Surprisingly, workers in the nonprofit sector, which has historically been hostile to unions, have also been capitalizing on this moment to organize. Katie Barrows, Vice President of Communications for the Nonprofit Professional Employees Union (NPEU), says, “Our local union represented employees at nine nonprofits in 2017, and has grown to represent nonprofit workers at 38 organizations, adding 21 units” in 2020. As nonprofit employees ourselves, we say: it’s about time.

However, while the growing number of unionized nonprofits is heartening, context is key: data from the U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey shows that in 2019, just 8 percent of nonprofit workers were members of unions, compared to 33 percent of federal, state, and local government employees. Though this moment is galvanizing nonprofit workers, we still have a long way to go.

Recently, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which was formed in part to protect workers’ rights to organize, has been accused of union-busting in multiple states, including Kansas and Georgia, amidst the national branch’s attempt to organize as well. In mid-December 2020, employees at the Animal Legal Defense Fund (ALDF) also informed their management that they intended to unionize with NPEU. The ALDF responded by refusing to voluntarily recognize said union, and quickly hired the notorious anti-union law firm, Ogletree Deakins (the same firm hired by the ACLU of Kansas) to quash these efforts. These examples are indicative of the nonprofit industry’s stance on unionization. This doesn’t come as a complete surprise: wealthy white people’s volunteerism and philanthropy in the 19th and early 20th centuries led to the formation of the modern nonprofit industry. In other words, the nonprofit sector was born out of capitalism, and relies on it to survive.

For many white collar employees, including those at nonprofits, the terms “union” and “labor movement” evoke images of early 20th century factories, full of soot-faced children in ragged clothing, working 16-hour days. We view the labor movement as history, rather than as an ongoing struggle. This conception is intentionally constructed via American education, which minimizes and decontextualizes labor history, if it’s taught at all. Americans’ skewed perception of the labor movement is strengthened by current anti-union laws, such as the misleadingly named “right to work” laws that suppress wages and enable discrimination in the majority of U.S. states. The time and station that separates modern-day white collar professionals from Gilded Age sweatshop workers prevents many of us from seeing ourselves as working class even though we are. To be clear, if you collect a wage for your labor, you’re a worker—regardless of your industry.

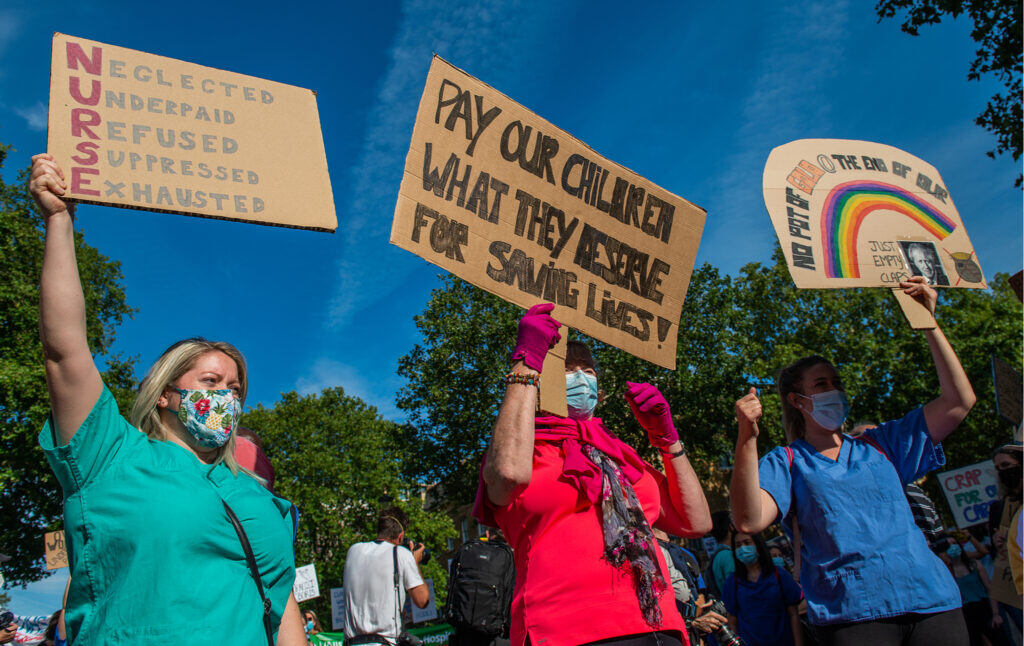

Today’s most visible unions in the U.S. exist in blue and pink collar professions (jobs historically considered to be “women’s work,” like nursing), which informs who we view as needing protection from their employers. Part of the myth of the nonprofit sector is that its employees don’t face exploitation. Many nonprofit workers have been led to believe that when an organization is pursuing a beneficent mission, it is also applying noble principles within its own walls—so why would unions be necessary?

But as journalist Corey Hill says in the East Bay Express, “nonprofit management sometimes takes advantage of employees’ desire to do good, and guilt-trips them into working long hours for low pay.” A 2013 Urban Institute survey assessing over 4,000 U.S. nonprofits supports this accusation: When money is tight, nonprofit leaders are more likely to increase staff workloads without increasing their pay than they are to cut programs. And we know that nonprofit staff are underpaid. For example, in 2017, Third Sector New England found that 33 percent of nonprofit workers in the region made less than $28,000 per year.

However, that same study found that average nonprofit CEO pay was over $130,000 annually, nearly five times as much as the lowest paid worker made. This might even undersell the problem at many nonprofits. The nonprofit sector is large and varied when it comes to organizational budget, CEO pay, and number of employees. CEOs of the largest nonprofits, like some health insurance companies and universities, make salaries that rival those of their for-profit counterparts—Peter S. Fine Fache of Banner Health, for instance, makes over $25 million a year. Executive directors of museums and other cultural institutions make somewhat less—a crowdsourced spreadsheet started in April indicates that the CEO of New York Museum of Modern Art makes approximately $5.1 million a year, but this is still over 127 times what the lowest-paid employee at the museum makes. Workers at the New Museum in New York sought to form a union in 2019 partially because of the chasm between CEO and employee pay. After negotiations, the museum agreed to a base salary of $46,000 for employees, which is still approximately 17 times less than the $768,000 [1] CEO Lisa Phillips makes.

Even the highest-paid nonprofit CEO is no Jeff Bezos. But extreme wage inequity in the for-profit industry does not exempt the nonprofit industry from examining disparity within its own institutions.

At the end of the day, nonprofits are businesses with a bottom line. This is why we need unions. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, union workers continue to receive higher wages than nonunion workers. A 2020 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research suggests that unions mollify the wage gap—it found that there was no gender pay gap among Wisconsin teachers until collective bargaining rights were gutted for public sector unions in 2011. Considering the nonprofit sector is almost 75 percent women, this is hugely significant. During the pandemic, with the ever-present threat of layoffs, employees are seeking to unionize not just for higher wages, but also for job security, advancement, and better benefits like childcare and paid time off. Barrows says that young nonprofit workers recognize these benefits of organizing: “A lot of these folks work at left-leaning or social justice organizations and want their employer to live their values and provide sustainable careers for themselves and their coworkers. They see that the way forward is with a union.”

A worthwhile mission doesn’t pay the rent. Organizations that insist otherwise perpetuate the expectation that nonprofit workers should sacrifice a living wage, work-life balance, and sufficient benefits in service of the “greater good.” This cruel tactic betrays the truth—nonprofits, like all businesses in a capitalist system, benefit from exploitation.

Historically, the labor movement has been bolstered by tragedy. The 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, for instance, led to widespread protests and demonstrations, the establishment of the New York State Committee on Safety, and significant workplace reforms that are still in effect today. During the pandemic, there’s been no shortage of tragic events, and just as in 1911, they are spurring collective action. The political upheaval of the past four years, growing climate instability, systemic police violence against Black people, and COVID-19 have added fuel to the proverbial fire. Nonprofit workers should seize this moment, but also remember this it is always the moment. Change happens when the exploited organize on their own behalf. As 20th century labor activist Rose Schneiderman said in a speech following the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, “I know from my experience it is up to the working people to save themselves.”