Hollywood, the Bush Years, and America’s Memory Hole

Our memories of history are shaped, in large part, by popular movies. What can we learn from the (few) films made about the Bush administration?

Everybody loves George W. Bush. He goes to football games with Ellen and it makes people believe in America. His friendship with Michelle Obama is iconic. Sometimes he’ll say something vague about Donald Trump being a bad guy. And he paints watercolors!

Dear reader, I am about to let you know something that may shock you. I know, I know, you love George Bush. But what if I told you that Bush launched a war of aggression on false pretenses? Or that he legalized torture? Or that he created a massive state surveillance operation that illegally spies on a billion people? Or that he oversaw the collapse of the world economy? What if George Bush was not just, as Ellen would have it, a guy with different political beliefs, but an actual war criminal?

It’s not just Bush who’s gotten this strange rehabilitation. Despite being one of the most significant events of this very strange century, the Iraq War has been thoroughly flushed down the memory hole. So has “enhanced interrogation.” Even stuff that is still happening—the Guantanamo Bay detention camp (still open and operating), the PATRIOT Act (still getting renewed with Democratic support), the Afghanistan War (still, somehow)—are treated both like a vague memory and an inalterable normal. You’ve got Politico reporting on Joe Biden’s historic decision to appoint the first Latino Secretary of Homeland Security, as if the Department of Homeland Security wasn’t created five minutes ago with the express purpose of doing the most horrible shit in the world. Colin Powell lied to the United Nations about Iraq having weapons of mass destruction, and he was a star attraction at this year’s Democratic National Convention. Former Bush staffers hoovered up liberals’ money to produce ineffective anti-Trump ad campaigns. The British Labour Party has returned to pining futilely for the glory days of warmongering Blairism, with Keir Starmar sacking MPs who voted against a bill to make British soldiers immune to prosecution.

But why has everyone forgotten the Iraq War, and all the crimes of the Bush administration? The mists of time don’t account for it. It’s been nearly fifty years since Watergate, and everyone still remembers that. Nobody has tried to rehabilitate Richard Nixon. Part of it is how much the war has vanished from pop culture. The Vietnam War cast a much longer shadow on American pop culture than the Iraq War did: basically every American film of the 1970s was about Vietnam, directly or indirectly, and plenty more have drawn inspiration from the war since. The biggest sitcom of the 1970s was set in the Korean War, acting as an allegory for the Vietnam War. The biggest sitcom of Bush’s first term was set in New York but never acknowledged 9/11.

So much of the story we tell ourselves about history comes through pop culture, for better or worse. But the crimes of the Bush administration have left hardly a dent there. I don’t think fiction has a responsibility to be historically accurate, but it nevertheless informs the shape of history in the public consciousness. At its best, art can show us truths a bare analysis of the facts can never quite reach. As activist, cultural critic, and NBA Hall of Famer Kareem Abdul-Jabbar writes, “Unless they’re making a documentary, filmmakers are history’s interpreters, not its chroniclers.”

Few films have tried to interpret the Bush era, but the ones that have are worth examining in detail. W., Vice, and The Report are some of the few major films about the Bush administration that Hollywood has produced, and despite their different approaches to history, each speaks to an important truth: to the personal moral character of George Bush; to the moral character of Republican Party in the decades before Donald Trump; and to why, exactly, America chooses to forget.

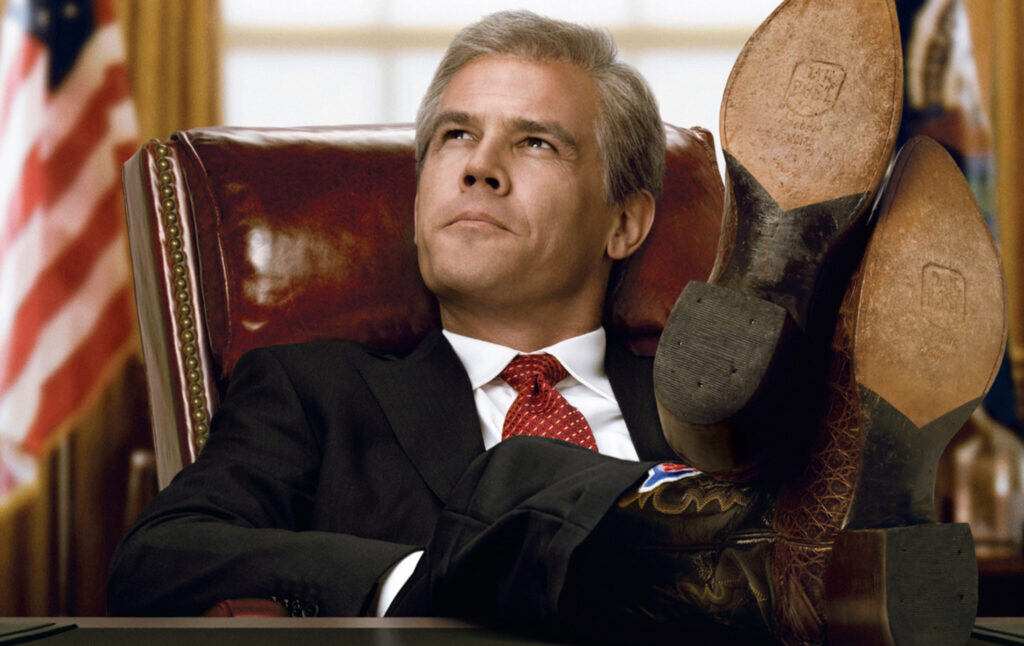

W. (2008): “You’re a Bush. Act like one.”

W. is the third of Oliver Stone’s films about the American presidency, after 1991’s JFK, a conspiracy theory movie about investigating Kennedy’s assassination, and 1995’s Nixon. The latter is a film that defies easy categorization: Nixon is Citizen Kane and it’s Scarface, it’s Shakespearean tragedy and a vampire movie. It’s a sprawling epic that plunges its hands deep into Nixon’s psyche. Anthony Hopkins’ Nixon is consumed by self-pity, so desperate for everyone in the world to love and respect him that he ensures the opposite. When JFK is killed, he sulks about not being invited to the funeral, then resentfully says, “If I’d been president, they never would have killed me.” Kennedy’s ghost never stops haunting Nixon— nor do the ghosts of his two brothers (whose young deaths from TB allowed his parents to send him to law school) and eventually, Bobby Kennedy’s, too. “Four bodies,” Nixon says, paved the path to his presidency.

W. is a more straightforward, restrained film than Stone’s previous films about American presidents, never delving into the conspiracy theory territory that is both JFK and Nixon’s bread and butter. Instead, W. is a tight little biopic structured through a series of flashbacks. It’s a funnier film—in a scene where the Bush cabinet brainstorms “axis of evil”, Karl Rove (a perfectly, perfectly cast Toby Jones) suggests “axis of weasels” and Bush (Josh Brolin) snaps “Don’t be cute, Karl!”—though hardly the wacky comedy it was marketed as. But it has the same strain of Shakespearean tragedy that runs through Nixon. If Stone paints Nixon as brought low by self-pity and resentment emanating from the traumas of his childhood, his Bush is defined by his relationship with his father: he wants to impress him, gain his love and approval, and escape from under his shadow, all at once.

While JFK and Nixon were about figures that were quickly being absorbed into history, W. was released when Bush was still in office (it premiered in October 2008). The common refrain was that it was too soon. “Why would we want to see the movie when we’re still in the movie,” the Washington Post asked, “and when it looks like we’ll be in it long after its protagonist has made his exit?” Time Out, in a mixed review, said that “without the benefit of hindsight, it’s probably the best we can hope for.”

But distance can dull our perspective as easily as sharpen it. Critics in 2008 seemed to assume —pretty reasonably—that Bush and his administration would live on in such infamy that there would be lots of chances in the future to commit this story to film in a fuller, deeper way. But hindsight tells me that the waning days of Bush’s presidency was probably the ideal time to make a movie about it, before any attempts to rehabilitate him kicked into full swing. I agree with the Sydney Morning Herald’s prediction: the film has matured quite nicely.

It is pretty funny to read reviews of W. that talk about it being too restrained, too sympathetic, unlike the damning portrait in Nixon, and then read contemporary reviews of Nixon where critics are surprised by its stylistic restraint and sympathetic characterization (grading on Oliver Stone’s curve, admittedly). Much like Nixon, I don’t think W.’s empathy for Bush absolves him of his crimes; it just contextualizes them. There’s a moment in Nixon where John Ehrlichman says, “You got people dying because he didn’t make the varsity football team. You got the Constitution hanging by a thread because the old man went to Whittier instead of Yale.” Nixon treats public office as a site to alternately act out and cure his neurosis—when he tells his wife that he’s running for president again, he assures her that this will be the thing to finally make him happy—rather than to make the world better, and it leads to devastating horror across the globe. (He eats a steak dinner while talking about bombing Cambodia, about dropping the big one if needs be, and there is quite literally blood on his hands.) The sometimes soapy psychodrama of W. makes the same point. You’ve got people dying because Jeb was always Poppy Bush’s favorite. You’ve got people being tortured because Bush hates to be called Junior. The film is called W., and that’s the only part of his name that isn’t his dad’s. That’s his to have, to own, for better or worse. The first time he meets his future wife Laura (Elizabeth Banks), he’s introduced as George Bush, Jr. “Call me anything but Junior,” are the first words he says to her.

James Cromwell is great as H.W.: cold, cruel, and openly playing favorites. He reacts to his son’s obvious alcohol problem with a series of increasing contemptuous lectures. “Who do you think you are?” he yells at one point, “A Kennedy?” One night George comes home drunk (again) and challenges his dad to a fist fight. When Jeb explains that George was celebrating because he got into Harvard—“I ain’t going, I just wanted to show you all I could do it,” says George—H.W. doesn’t give him an inch: “Of course he got in. Who do you think pulled the strings?” On the night George is elected governor of Texas, his dad can’t stop talking about how disappointed he is that Jeb didn’t win Florida.

That’s not to say that W. reduces geopolitics to a pop Oedipal complex. There are frequent flashbacks to Bush’s life, but the main narrative of the film is built around the Iraq War, the decision to invade, and what came afterward. Dick Cheney gives a PowerPoint presentation about Iraq’s oil fields while practically salivating: “Sixty of eighty oil fields are still undeveloped… We drain the swamp like Don says. We rebuild it. We develop its resources to the maximum. A nexus of power that won’t be broken in our lifetime.” When Colin Powell asks about their exit strategy, Cheney says, “There is no exit. We stay.”

W. is probably too generous to Powell, who acts as the voice of reason in scenes of the Bush cabinet, pushing back on Cheney’s ideas and expressing trepidation about launching a pre-emptive strike and getting quagmired in a forever war. Yet his characterization—as a man who expresses serious, unambiguous reservations in private but knowingly lies to sell the war to the U.N. anyway—is ultimately damning. But the film isn’t really about the people around Bush. Those in smaller roles, like Thandie Newton as Condoleezza Rice, are basically SNL impressions. “The film sees Bush’s insiders from the outside,” Roger Ebert wrote. “In his presence, they tend to defer, to use tact as a shield from his ego and defensiveness. But Cheney’s soft-spoken, absolutely confident opinions are generally taken as truth. And Bush accepts Rove as the man to teach him what to say and how to say it. He needs them and doesn’t cross them.”

A decade and change later, when Bush giving Michelle Obama sweets is treated as a light feel-good story, a portrayal that many deemed overly humanizing in 2008 feels like it has real teeth to it. Bush’s crimes in W. feel vivid and morally urgent, and the film never falls into the trap of portraying Bush as a helpless dumbass exploited by those around him. W. does have all the greatest Bushism hits—“In history we’ll all be dead,” “Is our children learning?” et al.—but it’s careful to acknowledge the degree to which Bush’s folksiness was an affectation. He loses his first congressional race when his opponent paints him as an out-of-touch Ivy League boy, and he swears that no one will ever out-Texan or out-Christian him again. When Cheney pitches him on “enhanced interrogation,” the softening language proves unnecessary: he tells Bush that they “utilize fear scenarios”, and Bush says, “You mean like pulling out their toenails?” and laughs, mouth full of pastry.

Vice (2018): “There are monsters in the world.”

If W. was too soon, 2018’s Vice was too late. Adam McKay’s Dick Cheney biopic was one of the most divisive films in recent memory, and for the naysayers, it arrived a decade late and a dollar short to tell us that some guy everyone knows is bad is, in fact, bad. Alissa Wilkinson in Vox spoke for many when she said, “I can’t figure out what Vice’s motives are, or what we’re meant to take away from the film.”

Vice is the second film of Adam McKay’s rebooted career of directing political comedy-dramas after a decade of making wacky Will Ferrell comedies. The first was 2015’s The Big Short, about different characters who predict the subprime mortgage crisis and bet against the American economy. Vice is a messier, more ambitious film than The Big Short, taking a series of swings so big that it inevitably misses a few. I mean, this is a film where Dick and Lynne Cheney have exactly one scene of mock-Shakespearean dialogue, where extraordinary rendition and a “fresh and delicious War Powers Act interpretation” are served up on a literal menu to Cheney and Rumsfeld, where the credits roll halfway through like the film’s over (seriously) when Cheney decides not to run for president. McKay wields montages of archive footage like prime Michael Moore and weaves big, unsubtle metaphors like Oliver Stone. It’s not the best film of his career (Step Brothers, obviously), but it is the most interesting, and probably my favorite.

While Vice is a biopic of Dick Cheney—Christian Bale, who funnily enough was originally cast as Bush in W., is brilliant in the lead, undergoing an extraordinary physical transformation without leaning on that instead of acting—the film is largely an account of the United States’ lurch to the right, telling the latter story through the former. It is, more than anything, an attack on the myth of the Good Republican, with whom you might have policy disagreements but who is fundamentally decent. Democrats have spent years talking about how Trump does not represent the GOP (even as the GOP have supported him through thick and thin). The Good Republican has been invoked throughout Trump’s presidency: it’s an appeal to universal values that reach across the aisle and an attempt to paint Trump as a unique aberration from the ordinary business of American politics. But when you try to locate the Good Republicans in history, they start to seem pretty elusive.

Through the person of Dick Cheney, Vice paints a damning portrait of the Republican Party from Nixon’s presidency to Bush II’s and stretching into Trump’s. We see figures familiar from the Trump administration pop up all the time. Jeff Sessions and Mike Pence appear in a blackly funny montage of politicians from both parties in the United States and United Kingdom arguing in favor of the Iraq War, intercut with bombs dropping and snippets of Budweiser’s famous Wazzup ad. John Bolton is mentioned as one of Bush’s advisors, and archival footage of Ronald Reagan shows “the Gipper” giving a speech about making America great again. “Early on in [promoting and making] this movie, some people asked me to compare [Trump and Cheney], to say who’s worse,” Adam McKay said. “And I answered the question, but really the answer should be they’re both part of an ongoing story, which is the rise of the right in America.”

The key scene, the one that everyone who hates Vice singles out as a reason why they hate it, comes when a young Cheney is working for Rumsfeld (Steve Carrell) during the Nixon administration. Rumsfeld points out to Cheney that Nixon and Henry Kissinger are meeting in Kissinger’s office—“Now why would Nixon not be meeting Kissinger in the Oval Office?” “He’s having a conversation he doesn’t want to go on the record?”—to talk about bombing Cambodia. Cheney is confused, since that would require congressional approval and Nixon campaigned on ending the war. Over shots of children playing in a peaceful Cambodian village, Rumsfeld explains:

“Because of the discussion that Nixon and Kissinger are having right behind that door, five feet away from us, in a couple of days, ten thousand miles away, a rain of 750-pound bombs dropped from B-52s at twenty thousand feet, will hit villages and towns all across Cambodia. Thousands will die, and the world will change. For the worse or the better. That is the kind of power that exists in this squat little ugly building.”

(As Rumsfeld speaks, you hear the helicopters. And then a bomb falls.)

Cheney struggles to ask Rumsfeld a question, stumbling over his words. Then he spits it out: “What do we believe?”

Rumsfeld laughs so hard he might choke, and then laughs even harder. “’What do we believe!’ That’s very good. What do we believe!”

The problem with this scene, as pointed out by no less than two separate articles in the Washington Post, is that Cheney was, even at this early stage of career, a committed neoconservative. If you interpret the scene totally literally, that’s a fair critique. But it seems obvious that the scene is a commentary on neoconservatism, and the American right more broadly. To refute the accusation that Cheney believed in nothing but accumulation of power for its own sake by pointing out that he was a neocon is to miss the point entirely. This scene, and the whole film, is asserting that those words mean the same thing.

Once you look at Vice this way, what might otherwise seem like a series of meandering vignettes snap into focus. The Cheney family watch Nixon’s resignation, and one of their daughters asks if the president is being punished. Lynne forcefully says that the president has a lot of enemies, and that when you have power, people will always want to take it from you. Dick is already on the phone to Rumsfeld with a plan to get into Gerald Ford’s cabinet. Much later, after their daughter Mary comes out as a lesbian, Dick says he loves her no matter what. When Lynne says, “This is going to make things so much harder for you,” she could be talking to either of them, but she’s definitely talking to Dick.

One of the film’s final sequences cuts between two scenes tied together by the most on-the-nose metaphor of modern cinema. I loved it. In one scene, Liz Cheney talks to her parents about her senate race: her opponent is using her gay sister Mary against her, accusing her of equivocating on gay marriage. Since Mary’s coming out, Dick has repeatedly protected his lesbian daughter, including deciding not to run for president because his opponents would go after her. But now, Dick nods his assent, and Liz goes on TV to spew homophobic bile. We cut between this and a separate scene of Dick getting a heart transplant. Dick has had so many heart attacks that they’re timed like a running gag, but before his heart gives out entirely, a donor heart becomes available. Up until now, our narrator (Jesse Plemons) has been mysterious, only explaining how he knows so much about Cheney by cryptically saying they’re “sorta related.” Then, suddenly, while he goes out for a run, he’s hit by a car and dies. His heart provides Dick with a transplant.

Tying these scenes together is almost audaciously obvious—Cheney is heartless, here’s his empty chest cavity to prove it—but there’s more going on there. It sheds the very last thing that made Cheney seem anything less than monstrous (his love for his family) and sacrifices that for power, too. It’s the very last thing that, in a generous moment, you could imagine motivating him other than power for its own sake: the thing that got him to stop drinking and getting into fights all those years ago was a promise that he’d never let Lynne down again. But that doesn’t have any nobler impulse behind it. Lynne also only cares about power. Because she’s a woman and so there’s a ceiling on what she can achieve, Dick is her conduit.

The heart transplant scene is also, as Emily VanDerWerff notes, a metaphor for the way Cheney’s generation “literally stole from the future to enrich themselves.” Jesse Plemons says his heart should give Dick another ten years. We watch all the results that spiraled out from the events of the Bush administration, a teacup on saucer on a teacup on saucer on a teacup on saucer. Flash on screen: the foreclosure crisis, the refugee crisis, the opioid crisis, terrorist attacks, children in cages. They’re all part of the bigger story Vice is telling, of the rise of the American right and the consequences for the whole world. The Bush administration is the lynchpin of that story.

The Report (2019): “They knew it didn’t work, and they did it again.”

Where Vice is big and bombastic, 2019’s The Report (stylized The Torture Report in the opening credits) is practically austere. Written and directed by frequent Steven Soderbergh collaborator Scott Z. Burns, it’s a classic formula well-executed: an All The President’s Men-style political thriller about the writing of the Senate Intelligence Committee report on CIA torture. It’s about the aftermath of the Bush administration’s crimes and in that way, acts as a kind of guide to why those crimes were erased from history. It’s a map of the memory hole.

Adam Driver plays Dan Jones, who is tasked with leading the Senate’s investigation into the CIA’s destruction of interrogation videotapes and, eventually, a much larger investigation into the CIA’s interrogation program. The film cuts back and forth between Dan and his team working on the report (largely sitting on computers going through CIA emails) and psychologists Bruce Jessen and James Elmer Mitchell, who are developing and applying “enhanced interrogation techniques” at the CIA after 9/11. The torture scenes—waterboarding, confinement boxes, sleep deprivation, rectal rehydration—are gruesome and upsetting, but never feel cheap or exploitative. They stand in hideous contrast to the shiny PowerPoint Jessen and Mitchell used in their pitch.

We see practically nothing of Dan’s life outside of work, and it’s made clear that there isn’t anything to see. The report becomes his sole focus, pushing out everything else, including sleep and keeping track of what month it is. He goes from a windowless room in a CIA building’s basement to the Senate offices to update Dianne Feinstein (Annette Bening) and other senators about his progress, and back again. His updates are delivered with moral urgency and a simmering rage that sometimes boils over. It takes him a long time to notice that he’s the only one who says things like “when the report comes out…”

Dan and his team experience a huge amount of hostility, from both the CIA and the Obama administration. The CIA is uncooperative well past the point of obstructionism. They won’t allow the investigators to interview agents, and then use Dan’s lack of interviews with CIA agents to discredit him. They initially don’t even provide Dan’s team with printers. And despite the CIA agreeing to provide all files relevant to the investigation, Dan says that files have “a habit of going missing.” But the agency goes full mask-off when the 6,700-page report is completed. They tie themselves in knots to prevent its publication, or to have so much of it redacted that it becomes incomprehensible. At one point, they object to agents being referred to even pseudonymously in case it puts their cover at risk. Obama-appointed CIA director John O. Brennan’s official response to the report claims that enhanced interrogation techniques provided unique intelligence. He says that “mistakes were made.” Dan keeps pushing, insisting that giving up means he’d just become part of the cover-up.

The Report has a lot of procedural intrigue, but it’s not dry and bureaucratic. The CIA illegally break in to the Senate computers and accuse Dan of stealing classified documents from the CIA computer system. It’s weird that this isn’t one of the most famous incidents in recent American history: surely it’s a constitutional crisis when an intelligence agency is hacking and browbeating a legislative body for investigating them. To me, it’s insane that anyone could think The Report is boring when it is so horribly stomach-churning. The film portrays the CIA as both endemically evil and terrifyingly powerful. We watch the CIA kill Afghani prisoner Gul Rahman—they dump a bucket of cold water on him and leave him in a freezing cold cell overnight, finding him dead in the morning—and then Dan tells Senator Feinstein that the agent who killed him was recommended for a performance bonus. The film rejects the idea that the CIA has changed in the meantime. As Dan says about Director Brennan, “He was Director Tenet’s Chief of Staff and then Deputy Executive Director when the program started. He grew up at the Agency.” When Senator Feinstein points out that Brennan claims to have objected to enhanced interrogation techniques, Dan says he’s spent five years going through emails and hasn’t found anything to suggest that’s true.

The Report depicts the Obama administration taking more of a softly-softly approach to burying the report, but its goal is the same. As David Klion wrote for The New Republic, “The Report may be the first major feature film to make the Obama administration look bad.” After Osama Bin Laden is killed, Dan is troubled by the CIA crediting enhanced interrogation techniques for leading them to him, which Dan knows to be a lie. Senator Feinstein calls President Obama to express concern, but all Obama says is that the mission was a success (“that’s the headline here”). Dan, confused, asks what just happened. “The CIA just got the President re-elected,” one of Feinstein’s staffers says. “That’s what happened.”

The cowardice of Obama’s technocratic dream team in the film will make your blood boil. Jon Hamm plays Denis McDonough, Obama’s deputy national security advisor and later chief of staff. He casually tells Dan that the report won’t be published when he meets him on his morning run. Dan asks if he’s read the report, to which McDonough whines about how long it is. He pathetically argues to Senator Feinstein that at least Obama admitted the CIA engaged in torture. To the Senate Democratic caucus, McDonough says they should focus on how wonderful it is to live in a country where such a report could even be written in the first place—and warns against taking any further action. “Now we go after Bush and Cheney on this, what’s to prevent the Republicans from coming back at us and trying to repeal healthcare?” he says. “We go after the CIA, maybe they say, ‘okay, well, immigration reform is off the table.’ Maybe it’s gun control.” The Report was made well into the Trump administration, and so this argument rings entirely hollow—not just morally bankrupt, but incredibly politically naïve. There’s nothing to prevent the Republicans from doing any of those things, whether you go after Bush and Cheney or not. They’re going to do those things, and worse, no matter how earnestly you try to meet them in the middle.

At one point, Dan considers leaking the report to a New York Times journalist. The journalist tells him that when Obama was elected, his administration considered setting up an independent commission to investigate the CIA’s torture program, like the 9/11 Commission, but decided not to. Obama had “just spent an entire campaign saying he was post-partisan, so going after the Bush administration flew in the face of all that,” the journalist says, ”…and this mess wound up with the Senate—and you.” The report, the journalist argues, was designed to get buried, to get clogged up in the Senate the same way everything else does. “They sent you off to build a boat, but they had no intention of sailing it. They probably didn’t think you’d get as far as you did.”

The journalist says that if Dan gives him the report, the Times will publish it—all of it, not just the executive summary that Senator Feinstein is fighting for—but Dan decides not to, saying he wants it to come out the right way. Divorced from context, this might seem like a condemnation of whistleblowers such as Edward Snowden or Chelsea Manning who leaked confidential information, positioning Dan Jones as more heroic for working within the system. But the rest of the film makes clear that trying to get information about the United States’ human rights abuses to the public “within the system” is as good as impossible. Aside from how hard Dan has to fight to just do his goddamn job, aside from being harassed and threatened by the CIA, The Report’s triumphant ending—Dan’s big victory—is getting the Senate committee who commissioned the report to publish the 525-page executive summary.

The ending seems, at first, like the triumph of liberal bipartisanship. The truth, or at least some version of it, does eventually come out. Annette Bening-as-Dianne Feinstein gives a speech about how this can never be allowed to happen again, and then there’s footage of the real John McCain’s speech that day, about how torture is both ineffective and morally repugnant. We hear a clip of The Rachel Maddow Show on TV, talking about the senators “doing everything they can to make sure this doesn’t happen again.” When the music swells and “In 2015, the McCain-Feinstein amendment was signed by President Obama, banning the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques” appears as superimposed text, it feels like closing the book. But this is sharply undercut when the text epilogue continues:

No CIA officers have been charged for the actions outlined in the report.

Many were promoted.

One of them became director of the CIA.

It’s a gut punch. You remember that torture was illegal anyway and it didn’t stop the government from doing it. You remember Dan saying a CIA officer testified before Congress that the use of coercive physical interrogation techniques in Latin America was proven to be ineffective and resulted in false answers. That before Latin America, they did it in Vietnam. “They knew it didn’t work,” Dan says to someone on his team, shock and disbelief audible in his voice. “And they did it again.”

These things get flushed down the memory hole through a toxic mixture of incompetence, indifference, and malice. The powerful want everyone to forget so that they won’t face any consequences and can do it all over again, and those who are meant to hold them to account—from the media to the opposition party—too often fail to do so, either to further their own ends or through sheer ineptitude. The more commercialized the media environment becomes, the more information becomes just another commodity to be bought and sold, not something precious to be preserved and passed down. Worse, it becomes just another site for the kind of manipulation of facts and history that creates these memory holes in the first place. During the Bush administration, the Pentagon planted analysts on the TV news networks, literally giving them their talking points. But it’s subtler stuff, too. Politicians use the media as a vehicle to present a likeable affect, to be the kind of guy that voters want to get a beer with. Watergate endures so much more in the public consciousness in part because Nixon’s public image was basically a cartoon villain anyway: he’d had a famously antagonistic relationship to the media.

But Watergate is also such a rare instance of there being consequences: a bunch of people went to prison, and Nixon had to stop being president. More often, those who abuse power are quickly rehabilitated. Ronald Reagan ignored the AIDS epidemic, set up an illegal propaganda agency inside the State department, and illegally sold arms to Iran to fund Contras in Nicaragua, but he presented himself as a smiling old patriarch with movie star charm. He not only got to still be president, he became a cornerstone of the Good Republican myth: it’s “the party of Lincoln and Reagan”, after all. One day, Bush’s name might be on that list, with his kitschy paintings and Southern-fried malapropisms obscuring any memory of the millions of lives he destroyed. The erasure of the Bush administration’s crimes is just a remarkably effective case of the system working as intended. You flush the abuses away, then start them all over again.