The Real Abbie Hoffman

Why it’s impossible to Sorkin-ize the great revolutionary clown.

At the end of his autobiography, Soon to be a Major Motion Picture, 60s radical activist Abbie Hoffman includes a sarcastic epilogue retracting everything he has ever believed. At the time he wrote the book, Hoffman was living underground, on the run from the law on drug charges, and he offered to give the following “confession” in exchange for readmission into respectable society:

You know, I’m really sorry and I wanna come home. I love the flag, blue for truth. White for right. Red for blood our boys shed in war. I love my mother. I was wrong to tell kids to kill their parents… Spoiled, selfish brats made the sixties. Forgive me, Mother. I love Jesus, the smooth arch of his back, his long blond curls. Jesus died for all of us, even us Jews. Thank you, Lord. … I love Israel as protector of Western civilization. Most of my thinking was the result of brainwashing by KGB agents… I hate drugs. They are bad for you. Marijuana has a terrible effect on the brain. It makes you forget everything you learned in school… I only used it to lure young virgins into bed. I’m very ashamed of this. Cocaine is murderous. It makes you sex crazy and gets uneducated people all worked up. Friends are kidding themselves when they say it’s nonaddictive. The nose knows, and the nose says no… Once I burned money at the stock exchange. This was way out of line. People work hard to make money. Even stockbrokers work hard. No one works hard in Bangladesh—that’s why they are starving today and we are not. … Communism is evil incarnate. You can see it in Karl Marx’s beady eyes, long nose, and the sneering smile behind his beard….Our artists are all perverts except, of course, for the late Norman Rockwell. …Our system of democracy is the best in the world… Now can I come back?

Part of Hoffman’s life is now indeed a major motion picture, Netflix’s The Trial of the Chicago 7, written and directed by The West Wing creator Aaron Sorkin. Sorkin is an unfortunate choice to bring Abbie Hoffman to the screen, since Sorkin’s basic worldview is one Hoffman completely rejected. The West Wing is known for showing a faith in good liberal technocrats to govern wisely, yet Hoffman was a “burn down the system” anarchistic radical. Sure enough, Sorkin’s Hoffman is almost the Jesus-loving patriot of the actual Hoffman’s biting satire.

The story of the Chicago 7 is one that needs to be remembered, so we can be glad that Netflix chose to bring it to the screen. After the 1968 Democratic convention, at which antiwar protesters clashed with Chicago police and were savagely beaten, shocking the country, the Nixon administration brought charges against a number of the event organizers. Nixon’s justice department wanted to teach the New Left a lesson in order to demonstrate it was serious about “restoring law and order,” and the charges against the defendants were flimsy. The trial itself was a farce, thanks in part to a biased judge who saw conviction as a foregone conclusion. But the defendants, instead of accepting their fate, decided to use the media attention being paid to the trial to publicize the cause of the antiwar movement, and called an array of celebrity witnesses (Dick Gregory, Allen Ginsberg, Jesse Jackson, Judy Collins, Norman Mailer, Arlo Guthrie, and even former attorney general Ramsey Clark) to “put the government on trial” and turn a political persecution into a media event that would keep the left’s message on the national agenda. Ultimately, while most of the defendants were convicted of conspiracy to riot, the convictions were overturned on appeal and the government dropped the case. The Chicago 7 trial’s historical significance is (1) as an example of the American government trying to criminalize dissent and intimidate the political left through selective prosecution and (2) as an example of how defendants can successfully fight back through turning a trial into a media spectacle and winning in the “court of public opinion.”

Abbie Hoffman, the most charismatic and media-savvy defendant, was one of the most colorful figures of the ‘60s left. Coming from a serious activist background as part of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Hoffman’s Youth International Party (Yippies) engaged in attention-grabbing stunts to publicize left causes. Infamously, Hoffman sneaked into the New York Stock Exchange and dumped dollar bills onto the trading floor, sending brokers scrambling for cash. In a giant antiwar march, he led a group trying to perform an “exorcism” of the Pentagon and send it off into space. At Woodstock, Hoffman scuffled with Pete Townshend of The Who when Hoffman stormed the stage to give a political speech. Hoffman’s Steal This Book gives advice on how to shoplift, deal drugs, and live free through all manner of scams.

Hoffman was an attention-seeker and provocateur, but he was also serious in his moral commitment to ending the Vietnam War, and his often-ludicrous counterculture antics came from a hatred of selfishness, authoritarianism, racism, and militarism. He was a utopian and an absurdist, but by pushing the boundaries of what civilized society could tolerate, he helped to make it freer.

Sorkin’s film does portray Hoffman relatively positively—even though Sorkin admitted he couldn’t really relate to him and found him somewhat intolerable—and Sacha Baron Cohen gives a strong performance. In fact, The Trial of the Chicago 7 presents Hoffman as charming, colorful, rebellious, and committed to using theatrics as a serious form of protest, a fun-loving counterweight to fellow defendant Tom Hayden, who comes across as a humorless prig (though a somewhat unpleasant note at the end of the film mentions that Hayden went on to serve a number of terms in the California legislature while Hoffman ultimately “killed himself,” perhaps Sorkin’s way of suggesting that in the long run the ‘work within the system’ types will prevail). Sorkin’s Hoffman is not held up as a figure of ridicule, but rather as someone who has a different notion of how to help the antiwar movement.

Yet while The Trial of the Chicago 7 is sympathetic to Hoffman, it also softens him in a way that ultimately amounts to historical fabrication. In the climax of Sorkin’s film, Hoffman takes to the stand and defends the protesters actions by invoking Lincoln and Jesus, and gives a tribute to democracy that could have come from The West Wing. [Update: have since discovered Sorkin in fact directly recycled West Wing dialogue for the Chicago 7 movie.] “I think our institutions of democracy are a wonderful thing that right now are populated by some terrible people,” Hoffman tells the court. In the film, Hoffman is a relatively benign spokesman for the basic right of dissent.

In reality, Hoffman’s testimony was far more radical. He even read out the Yippies’ list of demands, which included, among other things:

- an immediate end to the war

- “a restructuring of our foreign policy which totally eliminates aspects of military, economic and cultural imperialism

- the withdrawal of all foreign based troops and the abolition of military draft”

- “immediate freedom for Huey Newton of the Black Panthers and all other black people”

- “the legalization of marijuana and all other psychedelic drugs;

- the freeing of all prisoners currently imprisoned on narcotics charges,”

- “the abolition of all laws related to crimes without victims,”

- “the total disarmament of all the people beginning with the police,”

- “the abolition of money, the abolition of pay housing, pay media, pay transportation, pay food, pay education. pay clothing, pay medical health, and pay toilets,”

- “a program of ecological development that would provide incentives for the decentralization of crowded cities and encourage rural living,”

- “a program which provides not only free birth control information and devices, but also abortions when desired.”

Hoffman was a revolutionary, not just a critic of the war, and he said so plainly. But Sorkin cuts the bits of Hoffman’s speech that would endear him far less to a mainstream audience. For instance, Sorkin keeps the part of Hoffman’s sentencing statement in which he suggested Lincoln would have been arrested if he had done what the defendants did. He removes the parts where Hoffman offers the judge LSD, says riots are fun, calls George Washington a pothead, and says that Alexander Hamilton probably deserved to be shot. This stuff is, yes, clownish, but it was part of Hoffman’s effort to turn the whole proceeding into an absurdity.

Sorkin takes other creative liberties with history that end up distorting it. Sometimes these are arbitrary, small, and relatively harmless (defendant Lee Weiner was extremely hairy and hippie-ish but is presented in the film as clean-cut and nerdy). Bobby Seale, the Black Panther defendant who was infamously bound and gagged in the courtroom when he continuously spoke out about the violation of his right to counsel, actually managed to repeatedly wriggle out of the physical restraints the government put on him; the film portrays the government as effective in silencing him. Worse are things like portraying the prosecutor (an anti-communist ideologue in real life) as an agonized, conflicted idealist who sticks up for civil rights. Or showing Quaker pacifist Dave Dellinger punching a cop. Or treating the Panthers, armed revolutionaries, as peaceniks who preferred words to guns.

The film’s biggest problems come from the fact that Aaron Sorkin subscribes to an ideology I call Obamaism-Sorkinism (like Marxism-Leninism). The tenets of this ideology are that American institutions are fundamentally good, and that while we argue, ultimately our interests do not conflict, and nobody is evil or irredeemable. So of course the prosecutor is good. It could not be that Hoffman et al. want to destroy everything the prosecutor holds dear and create a society of sex, drugs, and rock & roll that would horrify him.

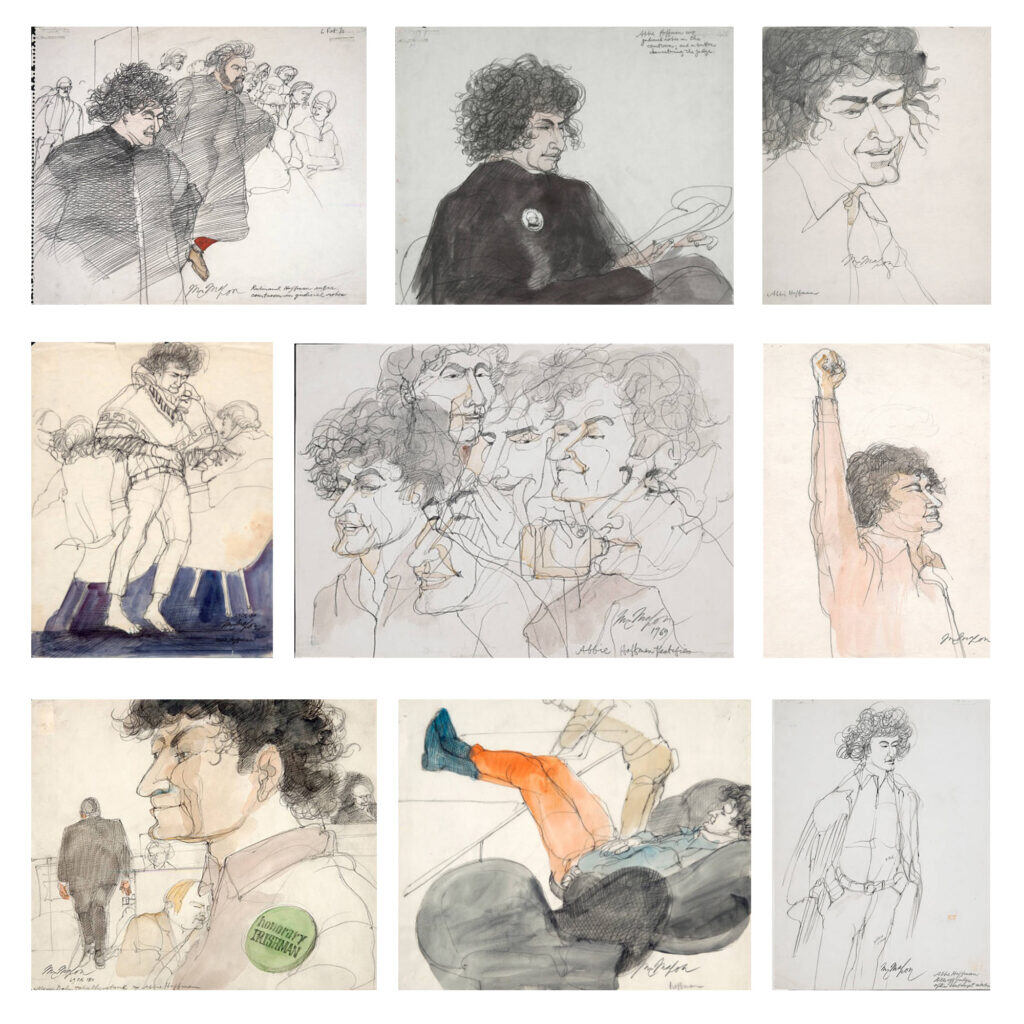

To me, the most disturbing way in which Obamaism-Sorkinism infiltrates the film is in the treatment of the Vietnam War. American liberals have a tendency to think of the war as a noble mistake, and to focus on the deaths of American troops rather than Vietnamese civilians. In reality, antiwar radicals did not usually speak in the name of the troops against the government, but instead spoke up for the Vietnamese. The Trial of the Chicago 7 shows protesters waving American flags; they would probably have been waving Viet Cong flags. (Hoffman got into a tussle with a court marshal when he tried to bring a Viet Cong flag into the courtroom, an incident captured in the courtroom sketches.) The film ends with Tom Hayden upsetting the judge by reading out the names of the American war dead. This incident didn’t happen, but what did happen at sentencing was David Dellinger making a plea on behalf of those oppressed by the United States:

[W]hatever happens to us, however unjustified, will be slight compared to what has happened already to the Vietnamese people, to the black people in this country, to the criminals with whom we are now spending our days in the Cook County jail. I must have already lived longer than the normal life expectancy of a black person born when I was born, or born now. I must have already lived longer, 20 years longer, than the normal life expectancy in the underdeveloped countries which this country is trying to profiteer from and keep under its domain and control… [S]ending us to prison, any punishment the Government can impose upon us, will not solve the problem of this country’s rampant racism, will not solve the problem of economic injustice, it will not solve the problem of the foreign policy and the attacks upon the underdeveloped people of the world. The Government has misread the times in which we live, just like there was a time when it was possible to keep young people, women, black people, Mexican-American, anti-war people, people who believe in truth and justice and really believe in democracy, which it is going to be possible to keep them quiet or suppress them.

Instead of choosing to end with a moment of tribute to American soldiers (as uncontroversial a statement as it is possible to make), Sorkin could have ended with the defendants’ real-life statements calling out the country for its hypocrisy and injustice. He decided not to.

There is something odd and troubling in the way that Sorkin has Abbie Hoffman cite the Book of Matthew on the stand, as if to suggest that every real American is a flag-waving patriot who loves Jesus and the troops. (Recall Hoffman’s epilogue.) In fact, one of the most interesting elements of the real Chicago 7 trial was an ongoing tussle between Abbie and the judge, Julius Hoffman, over the meaning of their shared Jewish identity (not to mention surname). Abbie Hoffman infamously threw Yiddish slang at Judge Hoffman, calling him a “schtunk” (stinker/vulgar person) and a “shanda fur die goyim” (a Jew who embarrasses other Jewish people by doing the dirty work of the gentiles). Abbie called the judge “Julie” and said he would have been a glad servant of the Nazi regime. Abbie Hoffman drew much of his approach to rebellion from Jewish culture—from Jewish anarchism and the prophetic tradition to the comedy records of Lenny Bruce—and he believed the judge was choosing to serve the WASP elite in its persecution of racial and religious minorities. (Interestingly, Judge Hoffman seemed to have a strange soft spot for Abbie; many of Abbie’s most savage criticisms were grounded in a moral appeal to their shared cultural ties.)

We see, in The Trial of the Chicago 7, some of the ways that the defendants mocked the court (such as, for example, by coming in wearing judicial robes and talking out of turn). But the transcripts are rich with absurdity, and I think Sorkin left most of it out because it doesn’t really make for a good courtroom drama, since it was a ridiculous courtroom comedy. Below are a few of my favorite snippets from a transcript loaded with ludicrousness:

From Allen Ginsberg’s testimony

MR. WEINGLASS (defense attorney):

Let me ask this: Mr. Ginsberg, I show you an object marked 150 for identification, and I ask you to examine that object.

THE WITNESS:

Yes. [Ginsberg is handed a harmonium and begins to play it.]

MR. FORAN (prosecutor):

All right. Your Honor, that is enough. I object to it, your Honor. I think it is outrageous for counsel to—

THE COURT:

You asked him to examine it, and instead of that he played a tune on it. I sustain the objection.

THE WITNESS:

It adds spirituality to the case, sir.

THE COURT:

Will you remain quiet, sir.

THE WITNESS:

I am sorry.

MR. WEINGLASS:

Having examined that, could you identify it for the court and jury?

THE WITNESS:

It is an instrument known as the harmonium, which I used at the press conference at the Americana Hotel. It is commonly used in India.

MR. FORAN:

I object to that.

THE COURT:

I sustain the objection.

MR. WEINGLASS:

Will you explain to the Court and to the jury what chant you were chanting at the press conference?

THE WITNESS:

I was chanting a mantra called the “Mala Mantra,” the great mantra of preservation of that aspect of the Indian religion called Vishnu the Preserver. Every time human evil rises so high that the planet itself is threatened, and all of its inhabitants and their children are threatened, Vishnu will preserve a return.

Abbie Hoffman pipes up about the jailing of David Dellinger

THE COURT:

Mr. Marshall, will you ask the defendant Hoffman to remain quiet?

MR. HOFFMAN:

Schtunk.

MR. RUBIN:

You are a tyrant, you know that.

MR. HOFFMAN:

The judges in Nazi Germany ordered sterilization. Why don’t you do that, Judge Hoffman?

MARSHAL DOBKOWSKI:

Just keep quiet.

MR. HOFFMAN:

We should have done this long ago when you chained and gagged Bobby Seale. Mafia-controlled pigs. We should have done it. It’s a shame this building wasn’t ripped down.

THE COURT:

Mr. Marshal, order him to remain quiet.

MR. HOFFMAN:

Order us? Order us? You got to cut our tongues out to order us, Julie. You railroaded Seale so he wouldn’t get a jury trial either. Four years for contempt without a jury trial. No, I won’t shut up. I ain’t an automaton like you. Best friend the blacks ever had, huh? How many blacks are in the Drake Towers? How many are in the Standard Club? How many own stock in Brunswick Corporation? [references to the judge’s condo building and an exclusive club for local Jewish leaders]

THE MARSHAL:

Shut up.

THE COURT:

Bring in the jury, please.

From the testimony of Timothy Leary

MR. KUNSTLER (defense attorney):

I call your attention to March of 1968, somewhere in the middle of March, and I ask you if you can recall being present at a press conference?

THE WITNESS:

Yes.

MR. KUNSTLER:

Prior to this press conference had you had any other meetings with Jerry and Abbie?

THE WITNESS:

Yes, we had met two or three times during the spring.

MR. FORAN:

Your Honor, I object to the constant use of the diminutives in the reference to the defendants.

MR. KUNSTLER:

Your Honor, sometimes it is hard because we work together in this case, we use first names constantly.

THE COURT:

I know, but if I knew you that well, and I don’t, how would it seem for me to say, “Now, Billy—”

MR. KUNSTLER:

Your Honor, it is perfectly acceptable to me—if I could have the reverse privilege.

THE COURT:

I don’t like it. I have disapproved of it before and I ask you now to refer to the defendants by their surnames.

MR. KUNSTLER:

I was just thinking I hadn’t been called “Billy” since my mother used that word the first time.

THE COURT:

I haven’t called you that.

MR. KUNSTLER:

It evokes some memories.

THE COURT:

I was trying to point out to you how absurd it sounds in a courtroom.

From the testimony of Judy Collins

MR. KUNSTLER:

Who was present at that press conference?

THE WITNESS:

There were a number of people who were singers, entertainers. Jerry Rubin was there, Abbie Hoffman was there. Allen Ginsberg was there, and sang a mantra.

MR. KUNSTLER:

Now what did you do at that press conference?

THE WITNESS:

Well—[sings] “Where have all the flowers…”

THE COURT:

Just a minute, young lady.

THE WITNESS:

[sings] “—where have all the flowers gone?”

DEPUTY MARSHAL JOHN J. GRACIOUS:

I’m sorry. The Judge would like to speak to you.

THE COURT:

We don’t allow any singing in this Court. I’m sorry.

THE WITNESS:

May I recite the words?

MR. KUNSTLER:

Well, your Honor, we have had films. I think it is as legitimate as a movie. It is the actual thing she did, she sang “Where Have All the Flowers Gone,” which is a well-known peace song, and she sang it, and the jury is not getting the flavor.

THE COURT:

You asked her what she did, and she proceeded to sing.

MR. KUNSTLER:

That is what she did, your Honor.

THE WITNESS:

That’s what I do.

THE COURT:

And that has no place in a United States District Court. We are not here to be entertained, sir. We are trying a very important case.

MR. KUNSTLER:

This song is not an entertainment, your Honor. This is a song of peace, and what happens to young men and women during wartime.

THE COURT:

I forbid her from singing during the trial. I will not permit singing in this Courtroom.

MR. KUNSTLER:

Why not, your Honor? What’s wrong with singing?

MR. FORAN:

May I respond? This is about the fifth time this has occurred. Each time your Honor has directed Mr. Kunstler that it was improper in the courtroom. It is an old and stale joke in this Courtroom, your Honor. Now, there is no question that Miss Collins is a fine singer. In my family my six kids and I all agree that she is a fine singer, but that doesn’t have a thing to do with this lawsuit nor what my profession is, which is the practice of law in the Federal District Court, your Honor, and I protest Mr. Kunstler constantly failing to advise his witnesses of what proper decorum is, and I object to it on behalf of the Government.

THE COURT:

I sustain the objection.

From the testimony of Abbie Hoffman

MR. WEINGLASS:

Did you intend that the people who surrounded the Pentagon should do anything of a violent nature whatever to cause the building to rise 300 feet in the air and be exorcised of evil spirits?

MR. SCHULTZ:

Objection.

THE COURT:

I sustain the objection.

MR. WEINGLASS:

Could you indicate to the Court and jury whether or not the Pentagon was, in fact, exorcised of its evil spirits?

THE WITNESS:

Yes, I believe it was. . . .

The defendants and the witnesses sang, they shouted, they showed utter contempt for the entire process. Defense attorney William Kunstler says that that “defense table was strewn with dozens and dozens of books (plus clothing, papers, candywrappers, and other assorted debris)” because the defendants treated the courtroom like their living room. They read books throughout the trial. They undermined the authority of the court at every turn, calling the judge by his first name (when they weren’t calling him a fascist) and thumbing their noses at all of his rulings. “Our whole defense strategy was geared around trying to give the judge a heart attack,” Hoffman joked, “because we weren’t going to beat the charge.” Sorkin portrays little of this, and I’m not surprised: how can someone who believes in process and institutions accurately portray the total breakdown of process and institutions that occurred in the Chicago 7 trial?

I have had a feeling of spiritual kinship toward Abbie Hoffman since my undergraduate years at Brandeis University. He loomed large among leftists on campus when I was there, as one of the university’s most famous alums—although one never boasted about on the admissions brochures. (The Sorkin film does contain a wonderful exchange in which buttoned-up Tom Hayden says to “tell Abbie we’re going to Chicago to protest the war, not to fuck around,” and Abbie replies, “Tell Tom Hayden I went to Brandeis and I can do both.”) Abbie was an inspiration because he was joyous, funny, and never sold out. He did somersaults in front of the courthouse. His colleague Jerry Rubin may have entered the world of business, but Abbie spent much of his post-1960s life fleeing from the government on drug charges, and then as part of the environmental movement. In the years just before his death in 1989, he was still a proud warrior for the counterculture. Fellow defendant Lee Weiner, in his autobiography Conspiracy to Riot, describes Abbie as “vibrant, aglow with energy and political wit and satire in the service of changing America and ending the war,” with “long untamed hair and a joyful, full faced smile.” He says Abbie was “impossible not to like—at least most of the time.” Abbie was a revolutionary with a spirit of optimism and fun, the kind of person the left needs if it’s going to build mass support.

Far from being a Jesus-loving patriot, Abbie Hoffman was a proud loudmouthed communist Jew who spat at everything pious and self-serious. (The epigraph of his autobiography is an anonymous hate letter he received that reads: “Dear Abbie: wait till Jesus gets his hands on you—you little bastard.”) Far from giving sermons on “the institutions of our democracy,” Hoffman defended the true spirit of democracy against our institutions. “I believe in democracy with a passion,” he said, “but it’s more than something you believe in, it’s something you do. We are very complacent because we live in Canada or the United States, we live in ‘democracies’—democracy’s not a place you live in, it’s something you learn how to do and then you go out and do it. And if you don’t do it, you don’t have it.”

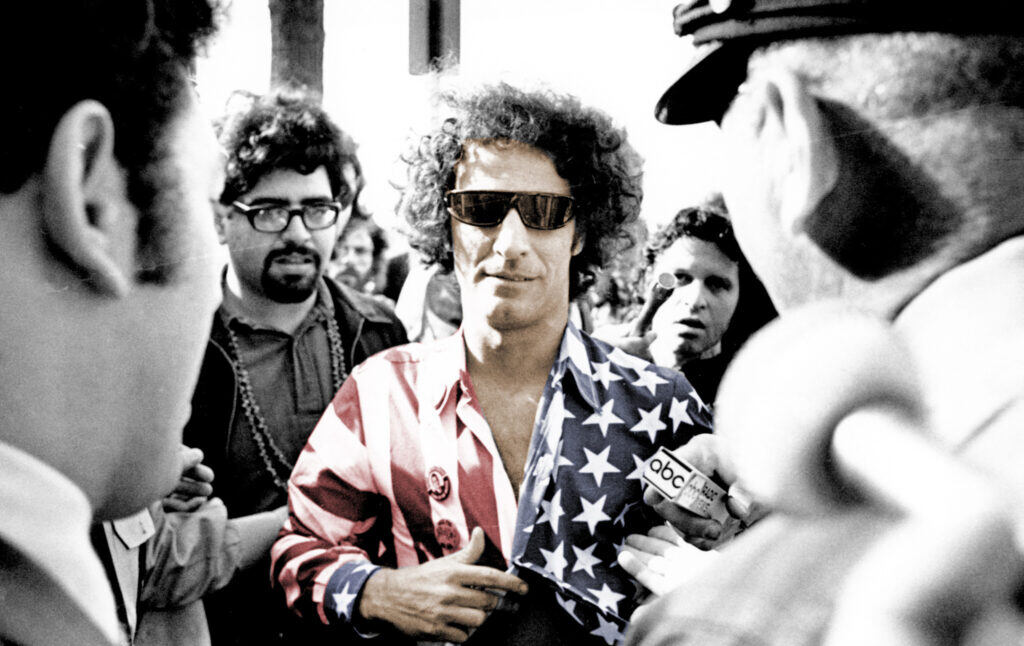

I like Abbie Hoffman because he knew how to, in his words, “make outrage contagious.” He pissed people off, but he did it in the name of values worth defending. When he wore his American flag shirt on the Merv Griffin show, the network censors were so horrified that they turned the entire screen blue for the duration of his appearance. In retrospect, it seems incredible that this could ever have been controversial, but the counterculture had not yet won. This was a time when people were roughed up and arrested for having long hair, before the right to abortion had been secured. America had to be liberated from the reactionaries and squares, and the hippies and yippies were a vital part of it.

When Hoffman spoke, he said, he “never tr[ied] to play on the audience’s guilt, and instead appeal to feelings of liberation, a sense of comradeship, and a call to make history. I played all authority as if it were a deranged lumbering bull and the daring matador.” This gleeful “fuck you” anarchist spirit is valuable. It is not people like the Abbie Hoffman of The Trial of the Chicago 7—those who dare to memorialize the troops and celebrate our institutions while critiquing them within reason—who are most essential to a thriving democracy. It is people like the actual Abbie Hoffman, who could never have been the subject of an Aaron Sorkin film, because Sorkin would never have been able to get a square liberal audience to like him. Abbie Hoffman was an American original, a great dissident clown who could never, and should never, be considered part of respectable society.

My colleague Oren Nimni and I recently interviewed Chicago 7 defendant Lee Weiner, who retains much of the same ebullient, defiant, optimistic ‘60s spirit. Listen here.