What To Do Once We’ve Defunded The Police

One idea: give the freed-up monetary resources back to the people through participatory budgeting.

In 2016, when the city council of Durham, North Carolina, proposed to invest $81 million in a new police headquarters, the Durham Beyond Policing coalition held an unusual protest. “Activists,” writes Brandon Jordan of Waging Nonviolence, “…handed fake money to protesters to put into buckets that represented different priorities for the community.” Durham Beyond Policing’s demand was for a participatory budgeting process—a clunky phrase that refers to people directly and democratically deciding how public money is spent, as opposed to politicians or bureaucrats making budgetary decisions. Their ask was clear: what would you do with $81 million dollars? Spend it on an institution that harms Black communities? Or spend that money on schools, mental health services, and free public transportation, among other options? What would a “People’s Budget” look like?

The new Durham police headquarters was ultimately built despite the protests, but the question has not gone away. What if we could all participate in deciding how to spend our public money? And how would the process work?

These days, defunding the police seems increasingly within reach. The Minneapolis city council has voted to move forward on abolishing its police department and develop a “transformative new model” of public safety. Municipal governments of all sizes around the country are likewise facing demonstrations demanding the defunding and abolition of police departments. Whether cities are simply cutting police budgets or literally abolishing the police, they will have to decide what to do with the money that is no longer being spent on policing. Depending on the city, defunding the police could mean the reallocation of tens of millions, hundreds of millions, or upward of a billion dollars toward other services. What would it look like to “divest” from the police and “reinvest in the Black and Brown communities they unjustly target”? What would it mean to assert “Black power through participatory budgeting?” And how can we make sure that budgets stay responsive to our communities’ needs even when we’re not in the streets?

Participatory Budgeting in Porto Alegre

A common place to start with participatory budgeting is to look at Porto Alegre, a city in Brazil with a population of over a million people. In 1989, Porto Alegre launched a wide-ranging participatory budgeting program. Due to constitutional changes at the federal level in Brazil, money was pouring into cities, and there was opportunity to experiment. The center-left Workers’ Party, which controlled much of the city government, led the drive to create a people’s budget.

For the first few years, the participatory budgeting process in Porto Alegre was messy and unwieldy. But once processes were established and people became engaged, the city entered into a sort of participatory budgeting golden age, which lasted from 1992 until a right-wing resurgence took over city government in 2004, mostly in response to mishandling of government affairs outside of the budget process. During this golden age, however, Porto Alegre demonstrated a level of sustained working class political participation and power rarely seen within a capitalist country, all centered around the city’s budget process. (PB still exists in Porto Alegre, but it has been chipped away at by the right in an effort to curtail access and reduce the amount of money allocated through the process).

For a Porto Alegre resident in the 1990s, participating in the city’s budgeting was a multifaceted and vibrant process. While there were many meetings, the process itself did not amount to something like attending a city council or public agency hearing. As portrayed in the documentary Beyond Elections, the annual process would kick off with festivities. It was a carnival-like atmosphere, with commissioned art, live music, dance numbers—a big civic-minded party that engulfed the city. The nitty-gritty of the process would begin with a recap of the status of the projects selected in years prior, discussed and debated in different neighborhood assemblies always attended by the mayor and city administration. When the mayor came to their neighborhood, residents would take the mic and demand answers. Why hadn’t the programs yet been implemented? Who was holding things up? Every year the city government would have to go on tour, taking the sorts of direct questions most city officials try desperately to avoid, and answering them to their constituents’ faces right in their own neighborhoods.

The radical differences between these neighborhood assemblies and the public hearings we may be used to cannot be overemphasized. This wasn’t a meeting about priorities set by city hall. The very residents demanding answers were the ones who had proposed, debated, and decided on the programs in previous years’ meetings. They had a direct stake in these programs and their outcomes.

Following the kickoff and accountability meetings, imagine yourself in a next round of neighborhood assemblies, designed to brainstorm programs and set priorities. What’s your pet issue? Is it sanitation? Housing? Transportation? Arts and culture? Something else entirely? You and your neighbors get to propose ideas and establish what should be top of the list in your neighborhood. These discussions, facilitated by non-voting City Hall-appointed facilitators, are tense but meaningful, and lead to concrete lists of ideas with ranked priorities. Neighborhoods could decide, for example, “to divide available funds into many small projects, such as paving 100 meters of dirt road in each of the 20 settlements, or spend them all on a major collective priority, such as a thoroughfare or a school.”

Upon priorities being set, the elected delegates from the thousands of participants and the added layer of elected “councilors” begin to construct an investment plan based on the countless hours of deliberations, taking part in their own continuous and intensive rounds of discussion. By the end of many months of debate and proposal development, the delegates and councilors complete their investment plans. Then the projects are voted on by everyone. Street committees monitor their status and progress. The process flows into and repeats the next year.

Now, imagine this is happening simultaneously in multiple neighborhoods within your district, and also in all the neighborhoods comprising the fifteen other districts. Everyone is in this together. There are billboards and ads on buses encouraging participation. The whole city understands that there are dollars to be spent, their dollars to be spent, and they feel responsible for what happens with that money. There are big signs proclaiming that implemented projects were funded through the people’s budget; after all, as a participant in PB expresses, “we were the ones that demanded, prioritized, and achieved them.”

In this scenario, you are also not just setting priorities for your neighborhood. You are setting them for the city. By the early 2000s, more than 30,000 people in Porto Alegre participated in the budgeting process each year. Participatory budgeting is such a universal activity that even your children get to set their own resource priorities. Every school in the Porto Alegre turned to its students to determine how to allocate funding.

In Porto Alegre, this broad community participation in the nitty-gritty of governance had knock-on effects well beyond the budgets themselves. As academics Emil A. Sobottka and Danilo R. Streck note, participatory budgeting in Porto Alegre “proved to have unforeseen consequences like questioning the traditional model of representative local democracy, widening the circle of people interested in political affairs, allowing the residents to question bureaucratic structures and to exercise a bit more control over their rulers.”

The results in Porto Alegre were stunning. Between 1990 and 2004, eighty-two percent of projects were implemented on time. Through participatory budgeting, access to running water increased from 75 percent to 98 percent of households by the year 2000. In that same period access to sewage lines increased from 46 percent to 98 percent. In 1988, there were 29 public schools, and by 2000 there were 86. In terms of housing, from 1986 to 1988, 1,714 families were provided with housing, whereas from 1992 to 1995, 28,886 families were housed. (The city population grew during this time, but the amount of infrastructure still increased dramatically even relative to that increase.)

Participatory Budgeting and Community Control

The Porto Alegre example is impressive, but could it be accomplished in the United States, and in the context of defunding the police? It’s clear the issues are closely interlinked: demands to defund and abolish the police have a long history extending back into the early years of the Civil Rights Movement, and activists have long called for Black community control over local governance. While in the sixties these calls were typically aimed at public education, community control has more recently also been linked to public budgeting. Since 2016, the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) has featured participatory budgeting as a central component of their community control platform. Organizers and officials have put forward demands for participatory budgeting in Seattle, Dallas, Memphis, Los Angeles, Durham, El Paso, and a growing list of other cities. The Portland City Council just voted to reduce the police budget and reinvest some of it through participatory budgeting. The Phoenix Union High School District recently decided to eliminate funding for school resource officers, and reinvest this $1.2 million through PB.

More than 3,000 cities around the world now have some sort of participatory process for budgets. There are even nationwide processes. In countries such as Portugal, people can pitch project ideas online and in-person. After developing projects that are regional and national in scope, Portuguese residents get to vote on two different categories of projects: those for their respective region and those pertaining to the entire country.

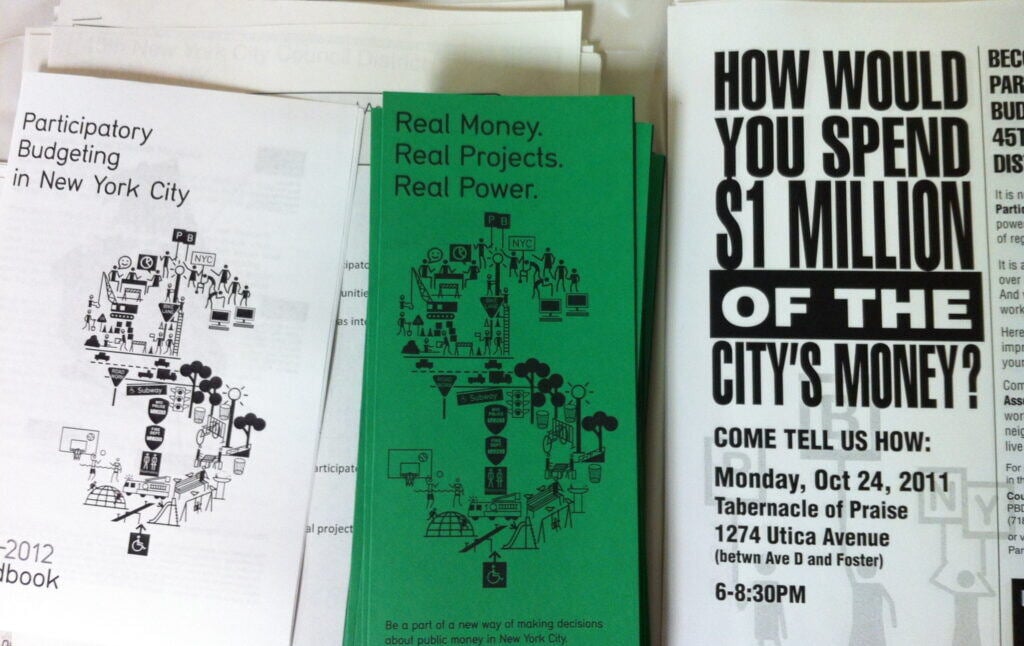

Advocates who initially met in Porto Alegre brought participatory budgeting in small steps to North America. The first system was introduced in Toronto public housing. Chicago rolled out the first process in the United States, and later on, New York City piloted participatory processes for portions of the budget within council districts. In recent years, participatory budgeting has increasingly been used in public schools, with K-12 students taking democratic control over their schools’ money. Examples like the Phoenix School District show that this can result in over 90 percent of the student body participating, with comprehensive school curricula that enable every child to suggest ideas, develop proposals, and vote. Today, New York City may be on the cusp of a citywide participatory budgeting process. Before the pandemic, New York City advocates were pressuring city hall to let residents directly allocate $500 million annually. In the context of the movement to defund the police, it could be much more.

Participatory budgeting processes in the United States generally start by holding what are called “idea-collection assemblies.” Here, members of a community generate ideas for what they would like to see in their neighborhood, city, school, or whatever they are budgeting for. In New York City, these assemblies have been driven by formerly incarcerated persons, and have seen “overrepresentation” by women and Black residents. In recent years, an online component has been added, where people can submit ideas online, with submissions mapped and made transparent to the public.

After the idea-collection assemblies, someone must develop proposals. In the United States, proposals are most often developed by “volunteer budget delegates” rather than elected delegates as in Porto Alegre. These volunteers are often people who, from their experience in an idea-collection assembly, are driven to develop their own and others’ ideas into full-blown plans. In this phase, laypeople meet with the relevant experts, such as administrators of an institution or city agency officials. In processes outside of the United States—such as in France, Australia, and Taiwan—budget delegates or those with similar roles are selected through sortition (i.e. the delegates are selected randomly by lottery, reminiscent of government in Ancient Athens). A sortition process is meant to ensure a fair cross-section of the affected community in developing the projects. It also ensures that technocrats and politicians cannot dominate the process. Whatever the project development phase looks like, it results in a ballot upon which the entire community will vote.

The next step is exactly this: a direct democratic vote. But it’s not a winner-take-all-vote. Rules for participatory budgeting almost always ensure that there is more than one winning project. People are able to vote for multiple projects, and multiple projects end up being funded. Projects that have won in New York City include funds for a “nonprofit Sakhi for South Asian Women to lead sewing circles for survivors of domestic violence.” Others have included “[a] series of workshops for immigrants, Muslim women, and their allies focused on self-defense techniques and empowerment.” Many infrastructure projects have been implemented over the years, allocating $210 million in total in New York City since 2012. These have ranged from installing rooftop greenhouses at schools, to bus time transit countdown clocks, to street resurfacings and new tree plantings.

As it stands, these projects are relatively minor. Participatory budgeting in the United States is a long way in scale and scope from allowing people to seriously define the priorities of a city, state, or country, as we saw happen in Porto Alegre. Now may be the moment to implement something like Porto Alegre’s system in the United States, with funds formerly allocated to police departments as the starting point.

Divestment from Police, Reinvestment in Black Communities by Black Communities

What happens if, say, New York City decides to implement full participatory budgeting—and residents still vote to keep paying the police six billion dollars per year? This is always a danger of democracy: sometimes people vote for bad things. And New Yorkers have, in the past, voted in favor of NYPD surveillance cameras. But votes like that one may have been driven by a misunderstanding of how surveillance program worked—for example,who would have access to the data—and ultimately lacked any meaningful alternative programs for that money. It’s one thing to be presented with a choice between cameras and no cameras. It’s another thing entirely to choose between surveillance cameras on the one hand, and jobs programs or school funding on the other.

There are two types of process controls to ensure that participatory budgeting doesn’t formalize oppression. First, the process itself can mandate that funds available be used only for restorative purposes. For example, M4BL recommends in its toolkit that activists and organizers “[c]reate participatory budgeting processes that allow communities to designate funding to public and community-based public safety infrastructure and programs outside law enforcement.” The Participatory Budgeting Project also has a recently-released toolkit designed to move forward with participatory budgeting in the specific context of divesting from police.

The other alternative, as seen in Porto Alegre, requires that the communities most harmed by police violence be given power over a greater proportion of the money formerly used to fund the police. The NYPD has a six billion dollar budget. Defunding the NYPD could do what Brazilian constitutional changes enabled in the late 1980s: open up massive resources for use in education, housing, and infrastructure. Briefly put, Harlem should receive a far greater proportion of money in a citywide PB process than the Upper East Side. This alone wouldn’t guarantee a turn away from policing, but it would ensure that the most affected communities would be the ones to choose policing or a form of it themselves, and that they would have the tools to keep the police accountable through the possibility of further defunding and reallocation.

The money is there. Our money is there. Countless infographics from cities of varying sizes depict police budgets towering over nearly all other budget categories. Communities United for Police Reform has put together the numbers for New York. Why should New York City have a budget where, for every dollar spent on police, only 29 cents is spent on homeless services, 25 cents on the Department of Health, 19 cents on housing preservation and development, 12 cents on youth and community development, and 1 cent on the workforce? Right now, cities across the country are asking this same question, and, moreover, the question of who is setting priorities and why. In U.S. city budgets, police have been a priority for the small set of powerful officials and wealthy donors who, for many decades, have been able to set priorities. To change this carceral state of affairs, we need to change who sets the priorities. We need to set the priorities.

What passes for democracy in the United States has long been an outsourcing of governance to small groups of people with specific interests and limited worldviews. But, little by little, in elections and in the streets, people are claiming the power that has been rightfully theirs all along. The business of government is not a boring pastime for wonks and technocrats, nor need it be the province and playground of the wealthy and powerful. Anyone who thinks public budgets are dull is misunderstanding their power and overlooking their role in our day-to-day lives. Deep democracy requires us to participate in power, and to draw meaning from that participation. Few places contain more power than the public budget. It’s time for us all to participate. In defunding the police and reinvesting via participatory budgeting we will have the opportunity to do just that: participate, at last, in power.

Alexander Kolokotronis is a PhD Candidate in political science at Yale University, where he researches participatory democratic schooling. He is on the Steering Committee of the Central Connecticut Chapter of Democratic Socialists of America, and an organizer for Concerned and Organized Graduate Students. He is on the Advisory Board of The Participatory Budgeting Project, and has designed and coordinated participatory budgeting processes. Prior to arriving at Yale, he worked in advocacy and development of worker cooperatives.