Jacuzzis in the Battlements: A Peek Into The Fantasy World of Grand Designs

We all want a dream home. Some of us might want it a little too much.

A house is one of the first things a child ever learns to draw. You’ve seen the same adorable picture a hundred times: a rickety box made from four shaky lines, then a triangle roof, a door, some more squares for windows. A stick figure family, standing outside the house on some uncertain plane—maybe floating just above the grass, or hanging out in some blissful space in the nearby air, waiting awkwardly for their Creator to learn how to draw perspective. In the corner of the paper, the sun is shining, blessing the family and their house with uninterrupted warmth and light.

Interestingly, as soon as children start drawing recognizable pictures, they start taking cues from the images around them, and if you ask them to draw a house, chances are they will draw the stereotypical Big Beautiful House, even if it’s not what their own home looks like. Kids are brimming with unique, bizarre fantasies—they want to be adventurers, pilots, dragons, firetrucks—but one of the most universal fantasies they put to paper is the big beautiful house, where the sun always shines.

It’s understandable why kids pick this up. Unlike becoming a dragon or a firetruck, it is theoretically possible to grow up and have your own house someday. Kids see houses all the time, in real life and on TV. What’s more, houses are a symbol of security and safety. For kids who are lucky enough to grow up in a household that is both financially and emotionally secure, the house is the place you go when the long, boring school day is over, where you play video games with your friends and drink hot cocoa while watching the rain. For kids who aren’t so lucky, the dream of the house might not be about the place they’re living now, but some imagined house of the future—some place they can claim for themselves, where they get to make their own rules, control their own life, keep their loved ones safe, and banish people who are dangerous. At its most basic, the dream of the house is a dream about self-determination—a right which all free people are supposed to have in theory, but is surprisingly rare in practice.

Most people don’t really get to choose where they live. Sure, if you’re a healthy adult who isn’t incarcerated, you can technically say no one forced you to live wherever you are now. But can most people truly say they have absolute control—absolute freedom—over the four walls and the roof that keeps them (relatively) warm at night? One in five Americans is a minor, for a start, and with a few rare exceptions, minors don’t get to choose their own home. Neither do the many elderly Americans and/or Americans with disabilities who have been deemed incapable of managing their own affairs and may be pressured into living with their guardian or moved into an institution; neither do the huge numbers of incarcerated people; neither do those on low or fixed incomes, who find themselves in a “take it or leave it” situation when it comes to low-quality, poorly maintained private or public housing. And some, of course, have no home at all.

As for those who are lucky enough to possess nominal freedom, and have some money in their pocket—can they really say they have full control over the place they call home? The average worker is strictly limited in their choice of abode by their job, their income, transit situation, and commuting time. If they can’t make rent without roommates, they will have to balance their own desires and demands for the decoration and operation of their home with those of other people. They may be unable to get a mortgage, leaving them subject to the whims of a landlord who not only refuses to fix the broken toilet or do anything about the toxic mold but may even deny their tenant the small pleasures of surrounding themselves with the things they love. Actually no, you can’t put up that awesome framed poster of a tree frog. Hanging a picture frame would leave marks on the wall. Even people in a position to buy a home aren’t truly, totally free. Most people’s budgets limit them to the purchase of a pre-existing building, which they may paint and garnish to some limited degree. But are they really creating their dream house? Is it everything they fantasized about when they were little?

For a privileged few, the fantasy is possible. Enter Grand Designs.

Grand Designs is a British reality TV show that has been airing on Channel 4 since 1999 and has cranked out nearly 200 episodes with no end in sight. (Series 13 and 14 are currently available in the United States on Netflix). Hosted by former set designer Kevin McCloud, the series follows wealthy property owners as they set about building their dream homes. This is not the humdrum world of the Property Brothers, who replace the carpet, knock down the odd wall, and consider it a “renovation” worthy of television. No, the people of Grand Designs dream much bigger than that. They buy fallen castles and disused water towers, they hire award-winning architects to sketch out story-time palaces, they spend years and unthinkable amounts of money creating the exact home they want, in whatever place they want.

(Side note: it is difficult to know what to call the people featured on Grand Designs. The word contestant is not appropriate, since there is no prize that they are after, and well, if you’re in a position to get on the show, quite frankly you’ve already won. Subjects might be more appropriate. McCloud adopts an Attenborough-esque curious detachment as the show’s subjects fumble their way through the process of design and construction: Observe the arrogant fool in his natural habitat. See him fire the project manager. Ah yes, this should be interesting, he is about to learn that everything has gone to shit. Oh, but now he emerges, resplendent in his triumph, playing croquet on the rooftop lawn, crossing the bright yellow steel bridge from traditional wing to modern wing.)

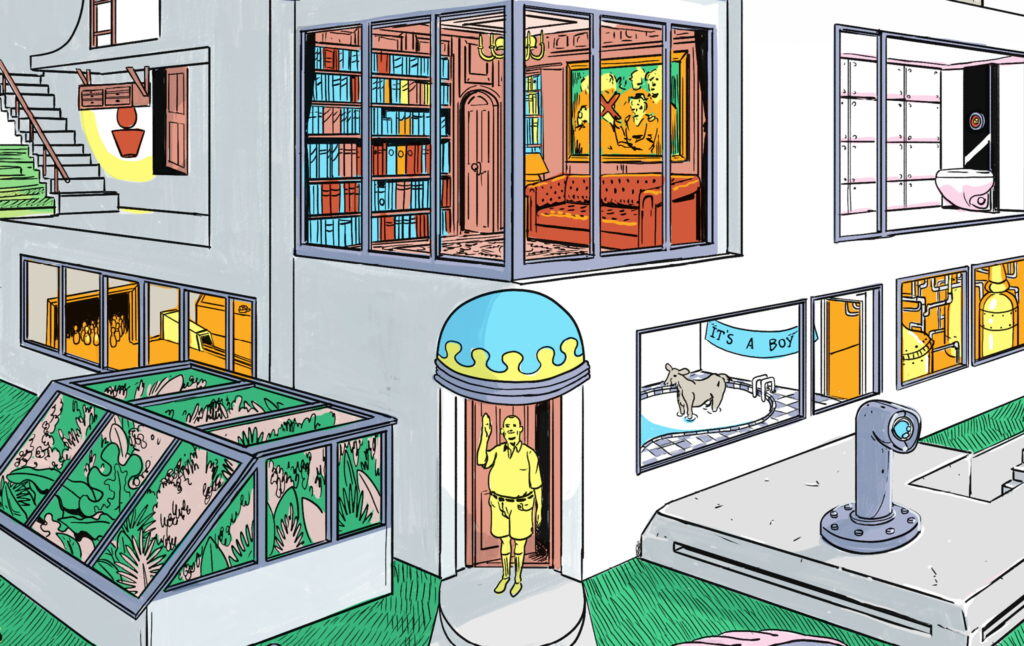

This is a show where fantasies come true. No balcony is too big, no turret too structurally unsound. The owners are not limited by the mundane expectations of the world around them. Theirs is not a house that came off the factory line, but a house that they dreamt, a house they have conjured. Even the theme music hints at the fairytale undertones: a playful arrangement of elfin strings, finished with a ludicrous glissando. You could easily imagine it playing at a theme park, or in a children’s movie about an enchanted forest. (The composer reports that some couples play it at their weddings.)

The basic structure of each episode goes like this: We are introduced to the creator, who has somehow got themselves in the position of having a piece of property and the resources to do whatever they want with it. The viewer is introduced to a virtual sketch of the creator’s plan, which usually involves materials and shapes completely anathema to the surrounding homes and natural landscape, and far more guest bedrooms than any normal human being might need. The show follows the homebuilding project over the course of months and years, during which time the creator will most likely encounter several unexpected obstacles, and inevitably go over budget (not that it ever seems to matter). They will make concessions, but there will be one or two aspects of the house that they have a bizarre fixation with, and will go to absurd lengths to make a reality (e.g., convincing an experimental materials lab in Switzerland to give them access to an new, untested type of concrete). Eventually, the dream is realized (most of the time), and they have their house. Sometimes the results are enviable, sometimes one feels they should have just bought a nice three-bedroom for half the price—but if you’re watching from a damp studio apartment, who are you to judge the tastes of these obscenely wealthy entrepreneurs?

(Well, entrepreneurs or whatever the hell they are. There is often vague talk of the budget and available funds, sometimes even bank involvement, but the source of wealth is almost never clear.)

Some of the creators are more sympathetic than others. In one cringe-inducing episode, an Irish actor bought a small mock-medieval castle, and attempted to fully renovate it without the help of an architect and without any actual sketches. (Behold, one of the few human beings who is unwilling to draw a house). Without any apparent self-awareness, he hired and fired his contractors at random, knocked down walls in the middle of the night, and was a source of constant frustration to everyone around him. He demanded jacuzzis in the battlements, and moodily intoned that he would build water-spouting gargoyles with the faces of his nemeses. This episode showcases the dark side of the dream of the Big Beautiful House: a man who, attempting to achieve his fantasy, becomes arrogant, monomaniacal, and ignores the needs of the people around him. (At one point, he fired his entire crew for seemingly no reason, at the height of Ireland’s brutal recession.)

For another example, check out the Mud House Man. The Mud House Man wanted to build a 10,000 square foot (!) home out of cob, which is an ancient straw-and-clay building material similar to adobe. Mud House Man touted the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the material, estimating that the home would be done in three months and cost £350,000. Two-and-a-half years later, when the show aired, the house still wasn’t finished. Five years after that, McCloud did a follow-up episode to check on the house. By this point it was finished, but the owner admitted that he had stopped keeping track of how much it cost. His marriage, clearly under strain in the original episode, had fallen apart, and he was living in the house with his new partner. The finished house is actually stunning and impressive if you can get past the ridiculousness of its size, and Mud House Man seems to think his “labour of love” was worth all the trouble. A reasonable person might have some doubts.

But a lot of the creators seem very nice, if a little weirdly obsessive about the shape of their roof corners. Once you get over the needling questions of where is all the money coming from? and why do you need both a Dutch tulip garden AND a Japanese zen garden?, it’s easy to get drawn into the fantasy. A nice family works hard for a few years, scrapes together the money for a home, and now they get to live in whatever type of environment they want—not an environment marred by the petty rules of a roommate, or a landlord, or the architect of some identikit suburban snoozehouse, but by their own rules, whatever anyone else might think of them. It’s compelling, and it makes you wonder what the world would look like if everyone could choose their own house.

It’s not clear, of course, that Grand Designs gives us any idea what the world would look like if everyone could choose their own houses. For all the peculiar demands made by the subjects, most of the finished homes end up looking very similar to each other. They tend to be sleek, modern, and minimalist. The amenities vary wildly, the exteriors vary a bit, but the aesthetics rarely stray from clean white surfaces, finished concrete, little ornamentation. Is this a feature of trends specific to a time and place? It’s easy to imagine that a show which tracked eccentric Americans instead of British and Irish people would end up with a lot more homes shaped like spaceships and hot dogs with interior design consisting of as many Conan the Barbarian action figures or authentic Dolly Parton wigs per square foot as the laws of physics will allow. Is it due to selection bias by the show itself? McCloud, who both hosts and writes the show, certainly has a deep affinity for modern design.

And, if we all could choose our own house, how many people would put in the effort to create something truly unique to them? For every thing in the world capable of expressing a truth about someone’s identity, there is always a spectrum of engagement. We don’t all choose to walk around covered in tattoos and piercings, after all. Some people have homes tastefully sprinkled with assorted items of curiosity, each with a story linking to a piece of the owner’s past. Others possess impenetrable seas of items with their own unique and unassailable importance. We often call this second kind of person a hoarder, and may think of them as hoarding things, but more often they’re hoarding stories; stories about their pasts and futures. What happened to them, and what still might, is embedded into each object. Parting with any of those things can feel like discarding a piece of themselves.

Still others surround themselves with artfully coordinated but contentless Etsy fluff. Things exist as part of their lives’ staging and little else. (Are people like this frighteningly empty or enviably detached? Is their identity undefined, or is it so secure that it needs no anchor on their shelves? Or do they maybe just genuinely like artful coordination itself, and find meaning not in specific items but a harmonious, comfortable, conventional whole?) The same goes for cars, clothes, everything else. Sure, lack of engagement is an engagement of its own kind (no fashion is still fashion), but there is still a difference between carefully curating a look with paisley and velvet and getting whatever will do at Target. There is a difference between driving around in a 1959 Cadillac and finding a nondescript, economical car to get from A to B. Few of us express ourselves in every available medium.

It’s not clear whether these questions would have been more or less absurd before the 20th century. Presumably, for much of human history, most people have either lived in structures that have been around for quite a while or that they built themselves. It may have taken suburbs, cookie-cutter property development, and Sears Roebuck kit homes ordered straight from the catalog to cement the idea of a house as a unique expression of personal identity. There can be no sneering at tract homes before tract homes exist. Our post-industrial tendency toward uniformity and overwhelming sameness (in service of access and affordability, sure) may have been necessary to birth the need for elaborate personalization. The overwhelming feeling one gets from the subjects on Grand Designs is a shared sense of rebellion, of breaking the mold and going their own way. This wouldn’t work for everyone: We’re not all mold breakers by nature. At the same time, that mold itself may be more recent, and more psychically oppressive, than is immediately apparent.

Still, an absolute mastery of the land is a powerful drug, and the appeal is obvious when watching Grand Designs. In one recent episode, which covered a few candidates for the Grand Designs House of the Year competition, a contestant was asked if he’d ever thought about selling his dream house, for which he had received several generous offers. The contestant slumped into a nearby chair and almost burst into tears. No matter how much money was involved, he would not give up his dream home, and the very thought of it was enough to make him cry. To people who might struggle to pay the rent every month, this attitude might seem unsympathetic—grotesque, even. But there’s a fundamental need for self-determination at work that is understandable. Maybe not all of us would go so far as to build a house in the middle of nowhere out of shipping containers, but most people have experienced the desire to have more control over the place where we sleep, eat, relax, and let our guards down. Most of us have felt frustration at an ugly stained carpet we weren’t allowed to replace, or a shitty uncomfortable dorm bed, or the weird sound in the pipes that just won’t go away. Living in a place that wasn’t meant for you can be an oddly debilitating feeling. Sometimes, when you’re moving from rental to rental, it can feel as though you’re even more transient and fungible than the weird mug and the old tin of beans that were in the back of the cabinet when you moved in and are still there when you move out.

It’s notable that no matter how nice and quiet and provincial the subjects of Grand Designs appear to be, and no matter how often and how eloquently they repeat that they want to build something that fits into and complements the surroundings, the houses they create always emphatically refuse to blend in—they are loud, their shapes are unnatural, there’s usually at least three different colors and textures involved. They stick out from the landscape and say, “What are you gonna do about it, punk?” They’re the ultimate expression of power over one’s own environment. And that type of power fantasy is something we can all relate to. Even if we’re still not quite sure what a “gable fronted dormer” is.