Why It Matters How Candidates Respond To Aggression Against Iran

The outcome of this primary may affect the destiny of entire nations. Candidates’ foreign policy views show us how much they value human life.

On Friday, January 3rd, Maj. Gen. Qassim Soleimani was assassinated by a Reaper Drone, alongside some 10 others, including high level officials of the Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces, on orders given by U.S. President Donald J. Trump. Assassinating a high-ranking official of a foreign government on foreign soil is an illegal act of war, a violation of the UN Charter’s prohibition on wars of aggression, instituted after the Second World War to prevent another global cataclysm. The Trump administration has claimed that Iran was in the midst of launching attacks on U.S. embassies, but we should take the pronouncements of the Trump administration about as seriously as intelligence community’s claims about Iraq in 2002, or a Trump tweet at 3:00 a.m. Serial liars lose the presumption of credibility. The administration has since predictably failed to provide any evidence that Soleimani’s assassination thwarted some kind of ongoing attack, repeatedly changing its story as to the justification for the assassination.

But to hear many top political leaders and media elites, the problem with attacking foreign nations with bombs is not that it violates the most important principle of law binding the nations of the world. Instead, they made the classic wishy-washy liberal argument: Of course Soleimani was a horrible guy, it’s just bad strategically to start a war with Iran.

Joe Biden’s statement began:

“No American will mourn Qassem Soleimani’s passing. He deserved to be brought to justice for his crimes against American troops and thousands of innocents throughout the region. He supported terror and sowed chaos.”

Former Mayor Pete Buttigieg asserted that:

“There is no question that Qassim Suleimani was a threat to that safety and security, and that he masterminded threats and attacks on Americans and our allies, leading to hundreds of deaths.”

Observe that Buttigieg did not provide evidence for the “hundreds of deaths” charge, nor did he mention that the “Americans” in question were occupying soldiers part of an illegal invasion of Iraq.

Elizabeth Warren repeated the unsubstantiated claim: “Soleimani was a murderer, responsible for the deaths of thousands, including hundreds of Americans”—objecting only to the wisdom of the action (“but this reckless move escalates the situation with Iran and increases the likelihood of more deaths and new Middle East conflict”). Senator Amy Klobuchar began with the same denunciation of Soleimani, before saying only that “the timing, manner, and potential consequences of the Administration’s actions raise serious questions” about the assassination. Note what’s missing: any question over the legitimacy and legality of killing nearly a dozen officials in two foreign governments.

In another clarifying moment on the fault-lines in U.S. politics, only Bernie Sanders and his few political allies in Congress denounced the assassination in clear and uncompromising terms. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez gave one of the strongest responses, writing:

“Last night the President engaged in what is widely being recognized as an act of war against Iran, one that now risks the lives of millions of innocent people.”

Senator Sanders and his campaign co-chair, Congressman Ro Khanna of California reintroduced legislation to prohibit funding for military action against Iran which they had fought to include in the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) just weeks before. After the amendments passed the House, Democratic leadership abandoned the provisions which would have limited aggression against Iran and halted U.S. support for the war on Yemen, leaving Senator Sanders and Ro Khanna to angrily denounce the military funding as blank-check for Donald Trump to continue and start wars.

Criticism of the assassination of General Soleimani from Democrats and in the press has been framed in terms of lack of proper planning. The killing was “ill-considered,” “poorly planned,” or “reckless.” But these descriptors dramatically downplay the gravity of the impacts of a potential war with Iran.

Discussion of war in Iran betrays ignorance of its implications

The history of U.S. military interventions in the Middle East during the past two presidencies makes clear the incredible human consequences of waging war. Our record in the region is despicable and it is worth tallying in order to understand just what is at stake in these discussions. When we understand what it is we’re actually talking about when we talk about “foreign policy,” it becomes clearer why candidates’ views on it should be central to our evaluation of them.

Somewhere between 665,000 and 1.2 million Iraqis have died as a result of the illegal U.S. invasion of that nation. Millions more were displaced from their homes, entire cities were destroyed, religious bigotry and factionalism has been fostered as a colonial divide-and-conquer strategy. Iraqi civilians have lived in constant fear of bombings as the occupying army fought a guerrilla insurgency. Iraqis have also lived in terror of the occupying U.S. forces themselves, who conduct “no-knock” night raids, and have carried out horrifying massacres of Iraqi civilians and other human rights violations with impunity. General James Mattis once bragged (before being appointed Secretary of Defense) that he deliberated “for 30 seconds” before bombing a wedding celebration, killing 41 civilians including 11 women and 14 children. The Iraqi economy, already decimated by years of U.S. sanctions, has been utterly destroyed, the professional and personal dreams of millions lost. 80 percent of Iraqis now lack sanitation, 70 percent lack access to clean water. How do most Americans even conceive of the pain and loss? Judging by the reaction of so-called experts, they simply don’t begin to try.

But as we know, the destruction of the target nation is just the beginning. Increased global terrorism is also the predictable result of U.S. actions. In 2002, many anti-war critics warned that an invasion of Iraq could lead to violence and instability throughout the region, and since then that is exactly what we have seen. The U.S. occupation of Iraq gave rise to increasingly radical insurgent groups, and eventually ISIS, which then helped turn a civil uprising in Syria into a horrifying civil war which has killed hundreds of thousands and destroyed much of that country.

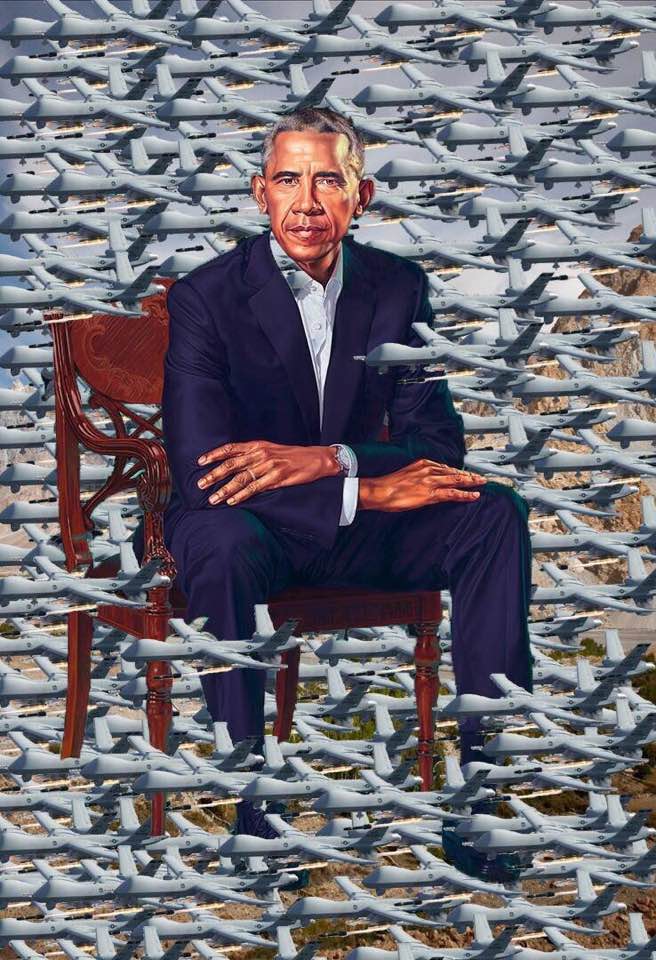

Disastrous and illegal wars of choice continued to be waged by President Barack Obama. Sure, Obama’s bombing campaign of Libya led to the brutal public lynching of Muammar Gaddafi, which gratified some. (A Reuters news headline gloated “Gaddafi caught like ‘rat’ in a drain, humiliated and shot” while Hillary Clinton famously bragged “We came. We Saw. He Died.”) But U.S. aggression in Libya led to ongoing chaos in the country—a recent BBC headline summed up the situation eight years later as “Libya in chaos as endless war rumbles on”—including wide-spread racial violence directed against Black Libyans. Unsecured Libyan arms ended up in the hands of Boko Haram. Both the weapons and the lawless situation helping Boko Haram grow, just like ISIS, into a powerful and brutal organization capable of terrorizing various nations and seizing large geographical areas (remember Boko Haram kidnapped 279 school girls? Over 100 remain missing years later). The Obama administration’s catastrophic action in Libya was followed by the brutal U.S.-backed Saudi bombardment of Yemen, which has killed more than 100,000 Yemenis, brought a huge proportion of the nation to the brink of starvation. The U.S. armed, refueled, and supported in countless ways a Saudi bombing so brutal it included blowing up a school bus full of 40 elementary school kids on a field trip. (One answer to the question: “Why does the Muslim world have such a low opinion of the United States?” might just be “because we provide explicit support to blow up busloads of Muslim schoolchildren and we massacre innocent civilians ourselves by the score, our corporations profit handsomely from it, and hardly any of us notice or care.”)

In its 19th year, the war in Afghanistan has claimed countless lives, and yet the Taliban remains as strongly entrenched as ever. Barack Obama went on to bomb at least seven nations including Somalia, Pakistan, and Syria as well as Yemen, Libya, Iraq and Afghanistan. Experts following wars during the Obama administration tend to include “at least” when totaling the number of Obama’s wars, due to the large number of covert military actions conducted in secret, including U.S. military activity which has spread across the continent of Africa. (As with immigration, any criticism of the Trump administration’s covert military activity is met with an obvious defense—Obama did the same thing.)

The long-term impacts of the Obama administration’s foreign policy are stark—the Obama administration has made ongoing warfare around the globe in the name of terrorism a seemingly permanent fixture of U.S. policy. Covert and illegal warfare in nations where no war has been declared or even authorized by Congress once served as a highly contentious turning point in the Vietnam War. When Nixon’s expansion of the war into Cambodia was revealed to the public, it sparked mass protests nationwide. By contrast, the U.S.-backed Saudi bombardment of Yemen had been accepted quietly, until the campaign led by Senators Chris Murphy and Bernie Sanders to stop it. Colonel Lawrence Wilkerson, former Chief of Staff to Secretary of State Colin Powell, recently put it quite bluntly: “America exists today to make war. How else do we interpret 19 straight years of war and no end in sight? It’s part of who we are. It’s part of what the American Empire is.”

Beginning with bold declarations of “bringing Democracy to the Middle East,” the wars of the past two decades have accomplished the opposite, almost certainly playing a role in the rise of authoritarianism in Turkey, and strengthening the hand of thugs and dictators everywhere. The refusal of the U.S. to leave the country after the Iraqi Parliament voted overwhelmingly to expel U.S. forces and massive protests by Iraqis calling on the United States to leave have made a mockery of the idea is interested in “promoting Democracy” abroad.

These are the basic facts of the recent experiences of U.S. military intervention in the Middle East. When elected officials and members of the press discuss war and coups abroad—talking about them from a purely “tactical” perspective, just another cost-benefit analysis of what will enhance U.S. power and benefit U.S.-based corporate profits—it conveys a shocking depth of both ignorance and callousness.

How Foreign Wars Cost the Working Class at Home

Many working Americans would respond to all this with the implicit or explicit question “Why should I care?” We can understand sentiments like “Sure it’s bad, but I’m being worked to death in two shitty jobs that I hate,” or “I’m completely overwhelmed trying to get my bipolar kid mental health care and wondering whether they will ever be able to live a normal life.”

But launching wars abroad does also have a profound impact on domestic politics in ways that affect working people. The political consequences of the war in Afghanistan led to the curtailment of Americans’ privacy and civil liberties with the passage of the PATRIOT Act of 2001 and the Homeland Security Act of 2002, along with countless executive actions which began the era of mass surveillance. Today every American’s phone calls and other communications are tracked, and can be tapped and listened to by a large number of government employees and private sector contractors at will.

War strengthens the powerful in other ways: The Bush administration passed a second massive wealth-redistribution tax cut for the rich which was so extreme that George W. Bush himself reportedly responded “Didn’t we already give them a break at the top?” After winning re-election by making the case to “stay the course” in the middle of two wars, Bush continued policies of redistributing wealth to the rich at the expense of the rest of us. These included signing new free trade agreements and (with Joe Biden’s help) passing a bankruptcy bill which limited the ability of indebted Americans to get relief from their creditors. War presents a giant opportunity for massive profiteering by corporate America (How many of the nation’s largest corporations have substantial contracts with the Pentagon?), while drawing away resources and attention from social investment. War has long been opportune cover for the rich and powerful to crush working people’s movements. Radical writer Randolph Bourne famously declared that “War is the Health of the State,” as the Woodrow Wilson administration used the cover of World War I to utterly decimate the IWW, the socialist movement, and much of the rest of the labor movement.

When campaigning against war, we must make the case: Working families are asked to sacrifice for wars while the rich and powerful always benefit. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Bernie Sanders’ responses to the Iran aggression nailed this aspect of anti-war messaging as well. AOC wrote “War is a class conflict, too. The rich and powerful who open war escape the consequences of their decisions. It’s not their children sent into the jaws of violence,” echoing a Sanders statement in the same vein. And if you’re still thinking “this all sounds terrible, but the issue I’m most interested in is student debt, or abortion rights,” remember that wars, once launched, have the power to reshape the entire domestic political landscape and wipe other issues from consideration. An atmosphere of fear and violence reinforces the power of every authoritarian, even more so when a right-wing government is already in place.

Just like the wars themselves, the domestic accoutrements of endless foreign wars are slated to continue on as a permanent bi-partisan reality: warrantless mass surveillance of every American’s personal communications, ever growing military expenditures, domestic police forces flooded with surplus military supplies and police trained based on anti-insurgency tactics, a stream of gravely wounded servicemen, and eruptions of racism against the refugees who flee our foreign policy in their home countries. We can now expect these policies to simply continue apace barring a significant shift to the left in American politics.

The Power of the Presidency and The Moral Imperative in the Presidential Primary

The Washington political spectrum has traditionally ranged from “We should brazenly defy international law and invade any country we feel like, for any reason, no matter how disastrous the consequences” (the view of John Bolton, former National Security Advisor to Bush and Trump) to “We should brazenly defy international law and invade any country we feel like, so long as we believe we are likely to get what we want out of it.” (This second position is grandiosely referred to as the Obama Doctrine.)

But as the media and political establishment begin to wake up to the fact that Bernie Sanders is in striking distance of the Democratic nomination, they are beginning to sound the alarm bells. On January 11th, The Washington Post ran an article titled “How Bernie Sanders would upend America’s global role.” From the article:

“I think it would be a fundamental shift, assuming his principles hold in the transition from campaigning to governing,” said Aaron David Miller, a former adviser to six secretaries of state and now a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.“You’ve had a consensus in this country on certain principles. Joe Biden represents that consensus. And to a degree, Obama as well.”

Ongoing international political developments during the long primary race have revealed a stark difference in the foreign policy orientation of the candidates. When Bolivian President Evo Morales was pushed from power by the Bolivian military and police forces in November, Sanders was the only leading presidential candidate to call the ouster a “coup.” Senator Elizabeth Warren, contrastingly, appeared to recognize the nearly all-white coup government as the legitimate government of the majority indigenous nation in the crucial first hours after the coup, referring to them as the “interim government.” It is telling that she would legitimize a military-installed government made up of political parties which have lost every election for the past 14 years, failing to forcefully denounce the coup even after its repeated murder of indigenous peasant activists in the streets. During the Bolton-Pompeo putsch to oust the Venezuelan Government—which featured none-other than ghoulish Reagan-era War criminal Elliott Abrams—Warren, joining Biden and Buttigieg, publicly recognized an opposition political figure, Juan Guaidó, as President of that nation despite the fact that no Venezuelan had ever voted for him to hold that office. She also supported the Trump administration’s brutal policy of economic sanctions, for which she was praised by the right-wing Wall Street Journal.

While Sanders has repeatedly criticized Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, he was nonetheless pilloried by Democrats for refusing to call Maduro a “dictator,” for opposing U.S. intervention in that country, and for refusing to tell the Venezuelan people who their president was. (Whether or not you’d like or would vote for a foreign leader doesn’t matter much when you’re talking about fomenting coups. There’s no sitting head of state in any country who shares my values. But I can see clearly that when the U.S. has backed a coup in a foreign nation, it has almost always led to terrible suffering. Just look at the horror in Honduras after the Obama-Clinton backed coup there in 2009.) Continuing the trend, Elizabeth Warren sided with Donald Trump last month in demanding increased military spending from NATO Nations, at the same time Bernie Sanders is calling for negotiated reductions in military spending, and has dangerously spread the totally unverified claim that Iran is “working on its nuclear weapon.” Warren’s foreign policy advisers are drawn from the Pentagon and the DC think tank world that propagates the pro-war, pro-sanctions consensus. In contrast, Bernie has chosen anti-war pro-Palestinian advisors like Matt Duss, his chief foreign policy advisor, who would represent a massive departure from decades of U.S. policy.

Once Sanders became the only unequivocal opponent of the assassination of Soleimani, the pattern became quite clear. Indeed, the tenor of Sanders’ criticism of the U.S.’ worst imperial adventures is virtually unheard of for a sitting senator. While being interviewed on Sarah Silverman’s Hulu show, Sanders said:

“And we can’t even use dirty words. This is the United States senate. We just starve little children. We go bomb houses and buses of children. And we give tax breaks to billionaires, but we don’t use dirty words.”

Sanders famously traveled to Nicaragua while Mayor of Burlington, Vermont, attending a large Sandinista rally in opposition to the U.S.’ ongoing support of the bloody Contra war which claimed some 40,000 lives, a significant portion of the small nation’s population. The Contras were trained, armed and supported by the United States, staged out of Honduras under the direct supervision of John Negroponte, then U.S. Ambassador to Honduras, who was later rewarded with such titles as Director of National Intelligence and Deputy Secretary of State. The Contras were famous for publicly murdering pro-Sandinista school teachers, their conduct in the dirty war was condemned by Human Rights Watch as “major and systematic violators of the most basic standards of the laws of armed conflict, including by launching indiscriminate attacks on civilians, selectively murdering non-combatants, and mistreating prisoners.” Sanders’ reaction to a New York Times reporter’s line of questioning was notable for how appropriately defiant it was:

NYT

In the top of our story, we talk about the rally you attended in Managua and a wire report at the time said that there were anti-American chants from the crowd.

SANDERS

The United States at that time—I don’t know how much you know about this—was actively supporting the Contras to overthrow the government. So that there’s anti-American sentiment? I remember that, I remember that event very clearly.

NYT

You do recall hearing those chants? I think the wire report has them saying, “Here, there, everywhere, the Yankee will die.”

SANDERS

They were fighting against American—Huh huh—yes, what is your point?

NYT

I wanted to—

SANDERS

Are you shocked to learn that there was anti-American sentiment?

NYT

My point was I wanted to know if you had heard that.

SANDERS

I don’t remember, no. Of course there was anti-American sentiment there. This was a war being funded by the United States against the people of Nicaragua. People were being killed in that war.

NYT

Do you think if you had heard that directly, you would have stayed at the rally?

SANDERS

I think Sydney, with all due respect, you don’t understand a word that I’m saying.

NYT

Do you believe you had an accurate view of President Ortega at the time? I’m wondering if you’re—

SANDERS

This was not about Ortega. Do you understand? I don’t know if you do or not. Do you know that the United States overthrew the government of Chile way back? Do you happen to know that? Do you? I’m asking you a simple question.

NYT

What point do you want to make?

SANDERS

My point is that fascism developed in Chile as a result of that. The United States overthrew the government of Guatemala, a democratically elected government, overthrew the government of Brazil. I strongly oppose U.S. policy, which overthrows governments, especially democratically elected governments, around the world. So this issue is not so much Nicaragua or the government of Nicaragua. The issue was, should the United States continue a policy of overthrowing governments in Latin America and Central America? I believed then that it was wrong, and I believe today it is wrong. That’s why I do not believe the United States should overthrow the government of Venezuela.

The fact that no sitting member of Congress—apart from perhaps Barbara Lee of California—is substantially and reliably to the left of Sanders on foreign policy does not excuse the many cases where he has chosen to support U.S. militarism. Bernie Sanders’ record on foreign policy leaves much to be desired—he voted to authorize military action in Kosovo and Afghanistan, voted for many military budgets, and for too long supported Israel’s criminal behavior towards Palestine. These actions were wrong, and we should be very clear about the limitations of Sanders’ independence from the war lobby. Ignoring these failings will risk confusing his positions with our own. And if he does become president, having a vocal and emboldened left willing to challenge the new administration on foreign policy will be more crucial than ever.

But Sanders does not need to be a peacenik or an anti-imperialist crusader to represent a major break in U.S. foreign policy that could save hundreds of thousands or even millions of lives and give crucial breathing room to progressive social movements and governments around the world if he were to be elected president. And Sanders’ record over the past four years has been promising. As the senator’s influence and power has increased since his presidential bid gained strength in 2015, he has only moved left. On Israel, Sanders has become the most critical major voice in U.S. politics; he has threatened to cut off foreign aid to Israel, he has been one of the few elected officials to call Israeli occupation and human rights violations as what they are, and he crucially intervened to defend Rep. Ilhan Omar at a moment in which Democratic leadership was preparing to essentially cast her out of the party for her criticism of Israeli policy. His prolonged campaign against the war on Yemen included successfully passing the first ever war powers resolution revoking authorization for an ongoing war effort. He has cast lonely votes opposing new sanctions on Iran, unlike Warren and every other senator in the race, and against increasing the military budget. And as noted already, he has been one of the only national political figures to forcefully denounce the coup in Bolivia and oppose the attempted ouster of the Venezuelan government.

Sanders has also articulated a progressive internationalist outlook, suggesting negotiating global draw-downs in arms spending in order to finance initiatives to address climate change, and to use U.S. negotiating power to raise labor and environmental standards rather then simply maximize profits for multinational firms. Given the reaction of Tunisian activists to finding out from leaked diplomatic cables that the U.S. didn’t actually really support their dictator anymore (They then overthrew the dictator), we could expect latent impulses to move left to be unleashed in many corners. Though not revolutionary, a relaxing of the neoliberal order would mean that many national governments may choose to increase investments in things like health, education, water, and public employment. While American political power has begun to ebb in the last decade, the U.S. still wields enormous influence in the affairs of every nation on earth.

Bernie is far to the left of Elizabeth Warren or Joe Biden in his opposition to wars and U.S.-backed coups abroad, and would mark the first real departure from Washington orthodoxy in decades. Given the immense power a U.S. president holds in international affairs, this upends the moral calculus of the race. Even assuming a Sanders administration were to continue many pugilistic elements of the U.S. global apparatus, the change between a President Sanders and decades of Washington consensus could mean the difference of millions of lives spared and save leftist movements and governments around the world from crushing U.S. intervention. He’s in striking distance of winning the Democratic nomination and has a strong chance to become President. Supporting Bernie Sanders’ candidacy over his competitors has become a moral imperative. A President’s conduct of foreign policy matters. It is not a side issue, even if the American media displays little interest in how this country’s actions affect non-American lives. In the presidential race, we must be clear about just what our militaristic policies have meant, and judge candidates by how much they value the lives of the victims of U.S. aggression.