Why “Free Stuff” Is Good

Funding public services through taxation instead of usage fees is fair and eliminates bureaucracy. We should do more of it.

If you ask Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar, free college is a handout for the rich. According to them, “working people” or people who “choose not to go to college” shouldn’t pay for rich kids’ college degrees. This may seem reasonable on the surface: You might agree that society at large shouldn’t subsidize wealthy people’s access to higher education. But the argument fizzles the moment you look at it seriously. High school, for example, is free at the point of service, and paid for by progressive taxation. Yet when it comes to higher education, the rich pretty much always go to college and graduate with shiny credentials, while the poor have fewer opportunities and—if they go to college at all—leave saddled with debt for life. Why is high school freely available for everyone, while college isn’t? Free K-12 education isn’t a right that descended from on high; it had to be fought for. Why shouldn’t college be free also? Why shouldn’t we cancel existing student debt? What things in our society should be free, and what shouldn’t be?

If you take Buttigieg and Klobuchar’s argument to its logical conclusion, you might say that nothing should be free on the off chance that rich people might use it. If you believe that society at large shouldn’t subsidize wealthy people’s access to any public goods, then we have to start charging wealthy people for public K-12 tuition, or to use libraries, or public parks, or roads, or police, or firefighting. This may sound mildly revolutionary in theory, but it’s quite the opposite in practice. If public goods aren’t freely available to all at the point of service, then they are no longer “public”—they’re just more or less expensive. Rich people have much more money, so paying college tuition or the library fee or cops to guard all 12 of their houses won’t deplete them nearly as much as it will the poor. Meanwhile, the only way for you, a poor person, to prove that you are “worthy” (i.e., poor enough) to deserve these goods you can’t afford is to submit yourself to means-testing.

What’s so bad about means-testing? It’s inconvenient, inefficient, and cruel. It places the burden on people who can’t afford the program to prove that they can’t afford it. Whereas universal programs place the parallel administrative burden on the wealthy through the tax system, means-testing makes the poor—who have less time, energy, and money—constantly prove and recertify their impoverished status to indifferent bureaucrats. Whether means-testing exists or not, the wealthy still have to pay their taxes, of course, but under the pressure of means-testing many poor people might rather just not go to college instead of spending years (like I did) fighting to make FAFSA work. And they might choose not to go to the library rather than fill out library fee waivers, not go to the park to avoid the annoyance of the park fee waivers, etc. We must always ask: Who carries the burden, both payment-wise and administratively? Who has to do the work, and is the work necessary? As Nathan Robinson wrote recently, we should be making things easier for people.

It is very useful to go through this reasoning exercise because, as it turns out, when we point out all the free and universal programs that currently exist (public school, libraries, parks, emergency services), we might also notice many more pay-at-point-of-service things that very much should be free and universal. Free college and Medicare for All have a special urgency right now thanks to the burden of student debt and the horror stories around the cost of medical services. But the justifications for tax-funded public schools and tax-funded public fire departments should lead us to ask what else ought to be delivered on this model.

Public Transit

Take public transit. Transit in general is a tremendously regressive area in the United States. Road maintenance, mostly benefiting those who drive cars, is publicly and universally funded, while mass transit like buses and subways are largely funded by charging fares to riders. Those riders, of course, have disproportionately less wealth than the drivers on tax-funded roads. We socialize transit for richer people, and force poorer people to pay per ride. We do this despite the ecological benefits of mass transit: You might think we’d want to incentivize people to ride buses and subways, but instead we incentivize them against it! And funding these systems through fares means that the NYPD can spend hundreds of millions of dollars abusing and arresting people who can’t afford their subway fares then, in true ass-backwards dystopian logic, say that this is necessary to keep the system funded.

Given that the pay-per-ride system for public transit is regressive, unjust, and cuts against the benefits of having mass transit even in a simplistic Econ 101 universe, there are shockingly few American cities that offer free and universal transit. Even internationally, pay-per-ride is the norm. What’s happening here? The answer is that cities around the world have been convinced that making public transit free invites only “undesirable” riders. This is disappointing to put it mildly, but I think it offers us a valuable lesson in how to approach our arguments for universalizing services.

A recent example is instructive. Kansas City, Missouri City Council recently voted unanimously to make its public transit system free. This has mostly been celebrated, but a Jalopnik piece cast doubt on whether it’s a good idea. Writer Aaron Gordon cited a 2002 report for the National Center for Transportation Research, which found that “while fare-free policy might be successful for small transit systems in fairly homogenous communities, it is nearly certain that fare-free implementation would not be appropriate for larger transit systems.” Is your racism detector going off yet? Might want to turn down the alarm volume for what comes next:

A fare-free policy will increase ridership; however, the type of ridership demographic generated is another issue. In the fare-free demonstrations in larger systems reviewed in this paper, most of the new riders generated were not the choice riders they were seeking to lure out of automobiles in order to decrease traffic congestion and air pollution. The larger transit systems that offered free fares suffered dramatic rates of vandalism, graffiti, and rowdiness due to younger passengers who could ride the system for free, causing numerous negative consequences. Vehicle maintenance and security costs escalated due to the need for repairs associated with abuse from passengers. The greater presence of vagrants on board buses also discouraged choice riders and caused increased complaints from long-time passengers. Furthermore, due to inadequate planning and scheduling for the additional ridership, the transit systems became overcrowded and uncomfortable for riders. Additional buses needed to be placed in service to carry the heavier loads that occurred on a number of routes, adding to the agencies’ operating costs.

The problem with fare-free systems, you see, is that the riders are not “choice riders” and that these non-”choice” riders were rowdy and did vandalisms. Note that these results come from three fare-free experiments: one year programs in Denver and Trenton in the 1970s (but only for off-peak hours) and a full fare-free experiment in Austin from October 1989 until December 1990. So, if pearl-clutching about non-”choice” riders and young hooligans doing graffiti sounds straight out of the 1970s The Warriors fanfic, or a product of “super-predator” politics, that’s because it is.

Notice what else is going on here. “Vagrants” onboard buses bothered other riders. Ridership overall went up, which is viewed as a negative because the city failed to accommodate the increase with more service. So the reasons we shouldn’t have fare-free transit are: (1) we have made it illegal and/or untenable to exist in so many physical places as a houseless person that people with nowhere else to go will spend their time on free buses; and (2) more people rode transit overall. Because we have failed to house our neighbors (despite there being more empty houses than houseless people, even on a city by city basis), and because we don’t want to actually meet demand with funding, the report concludes that we have to keep our horribly regressive transit funding model.

This is a clever rhetorical move. The report and Jalopnik article conclude that free public transit doesn’t work because (due to our failure to house people and provide sufficient bus service) people still drive their cars. Getting cars off the road is a reason to make public transit free, but it’s not the only reason. The report and the Jalopnik article quietly shift the goal of free public transit so that it is only focused on reducing drivers and not at all on equity. Fare-free systems are failures because they don’t cause people to shift from driving to riding the bus. Of course they don’t. Someone who drives 12 miles round-trip to their office every day, following several direct bus routes, doesn’t do that to avoid paying the $4 roundtrip bus fare. The incentive against driving is helpful, but it can’t be the whole reason to do fare-free public transit.

Instead of focusing on drivers, the best reasons for fare-free transit are about the riders. Ridership in all of the fare-free experiments increased, sometimes dramatically, meaning that people were avoiding public transit due to the fare. Some of those people might have been looking for a free place to sit, but if overcrowded buses were a complaint, then it is a safe bet that many were going places they wouldn’t have otherwise gone because they could do so for free. This is a good thing. Those people might be going to work, or to buy things, or just to visit friends or feel a little bit of joy they wouldn’t have otherwise felt. Transit justice should be about people being able to move around, to live their lives as they see fit regardless of wealth.

Once again, you can argue here that what you really need is means-testing: free rides for people under a certain income threshold, so that little Trumps do not get to ride the bus without paying. But we can give the same reply: Assessing people’s income before they can ride the bus is humiliating, inconvenient, administratively costly, and will inevitably mean that people who should be entitled to ride the bus free, and would do so, choose not to. Not to mention the administrative costs created for the transit system of evaluating and tracking riders’ income, buying, maintaining and upgrading fare collection equipment, and policing fare evasion. All of this is unfair and unnecessary. We need to say so loudly and clearly.

Utilities

Utilities can be a little bit more difficult to conceptualize as public goods that should be free. For one, rather than a service that the government is providing, like education or transit, utilities deliver goods, and those goods often have a per unit cost. The cost of free public education is constrained by the number of students in a community. The cost of free public transit is constrained by the number of potential riders. But there is no natural constraint on the cost of free public water service. Maybe if water service was free, everyone would take hour-long showers and dig out personal swimming pools. Maybe they would run every hose and faucet 24 hours a day just for fun. Maybe they would be so wasteful that they would destroy city governments and the climate simultaneously.

But, at the same time, the pay-for-water system is a horrendous injustice for poorer people. Cities that fund most or all of their water infrastructure through service charges are hiking rates across the country. In cities like Cleveland that have seen decades of population reduction and shrinking incomes, water rates paradoxically get more expensive, because the system costs are spread among fewer users. Water rates are increasingly unaffordable by every official metric in cities across the country. And the consequences for being too poor to afford water service are dire. 15 million Americans had their water shut off in 2016 for failure to pay. That means more than just not being able to drink from the tap. That means no bathing and no flushing toilets. It means dramatically increased risk of disease. It also means a serious risk of child protective services taking children away. And, in places like Cleveland, failure to pay those increasing water bills (and ever-mounting fees and interest) can lead to people losing their homes altogether (with water-related foreclosure significantly more likely in predominantly Black neighborhoods). And yet, for all of the attention and effort paid to trying to extract money from people who use water because it is necessary to maintain water systems, those systems in the U.S. regularly and catastrophically fail.

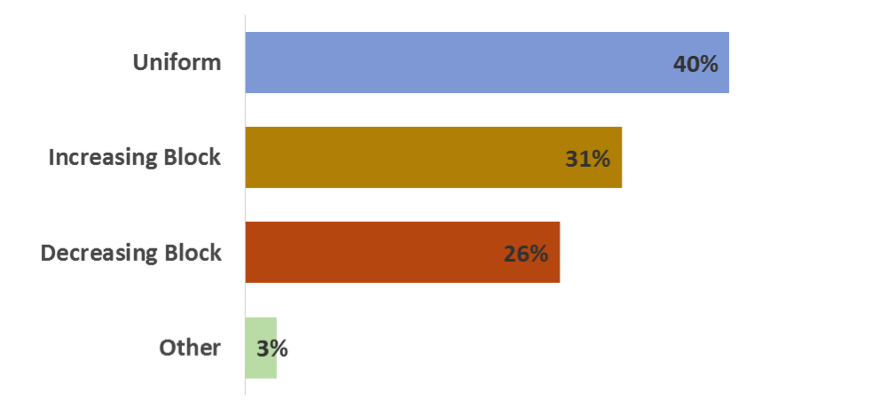

And are our water systems really solving the freeloader problem? Water use in many states, especially those that are prone to droughts, is notoriously skewed toward industrial, corporate, agriculture, and even bottling and shipping (which sometimes counts as “urban” because bottlers often get their water from municipal systems). Many water systems offer “decreasing block rates,” which is essentially a bulk discount—users pay a lower per-unit water rate if they use more water. This means that poor families end up paying a higher rate to subsidize giant corporate users.

Given that water service is necessary for public health, not to mention human dignity, it should be deeply disturbing that we condition water on ability to pay. But is there a way to do free and universal water service without subsidizing swimming pools?

Of course there is. The way to do free and universal programs for things like water is to make them free up to a point. (Some might claim this is not a truly free and universal program, and that’s fine.) Everyone should be able to access a reasonable amount of water, electricity, gas, and internet service. And rather than making this happen through a subsidy based on income—and thereby burdening people with means testing—it should be a set supply subsidy. Residential users should get up to a predetermined amount of water (and other utilities) for free every month, and should only be billed by unit if they draw more than that amount. The system costs currently paid through rates should be paid through taxes and increased rates for commercial users.

How do we determine what the appropriate allotment is? Won’t this involve some kind of central planning bureaucratic process? Yes! And that’s part of the point! Water (like gas and power) is a shared, essential, and limited resource for which we all have a common need. Leaving its allocation to markets has resulted in countless and still developing disasters.

* * * *

What we need in the provision of water, gas, electricity, transit, medical care, education, and public spaces is more democracy. We need more recognition that these are public resources serving the public good, and that they should never have been treated as luxuries only available to those who can pay. When we accept this, we also accept the responsibility to fund and allocate and govern them wisely and democratically. We accept responsibility for our neighbors’ wellbeing. We have always had this responsibility, we have only pretended not to. Universal programs, whether they’re free college, medicare for all, free transit, or free utilities, are simply a correction back to what’s right.

It shouldn’t be difficult to convince people of this, because most of them already believe it. We take for granted “free stuff” like roads and fire departments and schools. There should be nothing radical about asking the question: What else clearly needs to be governed on the same model? In what other domains of life does “pay per use” end up causing avoidable injustices? When critics of free college point out that everyone would get it (as if this is a bad thing), we should not only point to all the other things they already get for “free,” but should make the case for free things generally and demand further application of this important principle. Let’s get that chocolate milk flowing.