Why do leftists dislike “liberals” so much? Why is there a left-liberal divide at all? Isn’t “liberal” just a term for those progressives who have a somewhat more incremental view of how social change happens? If we all want the same things, but some people believe in going a little slower and some people a little faster, can’t we all Agree To Disagree?

Because I am diplomatic and well-disposed toward my fellow human beings, I always struggle a bit with this. I do want to heal divides, especially when the other party shares my perspective on many important things. I am wary of “circular firing squads.”

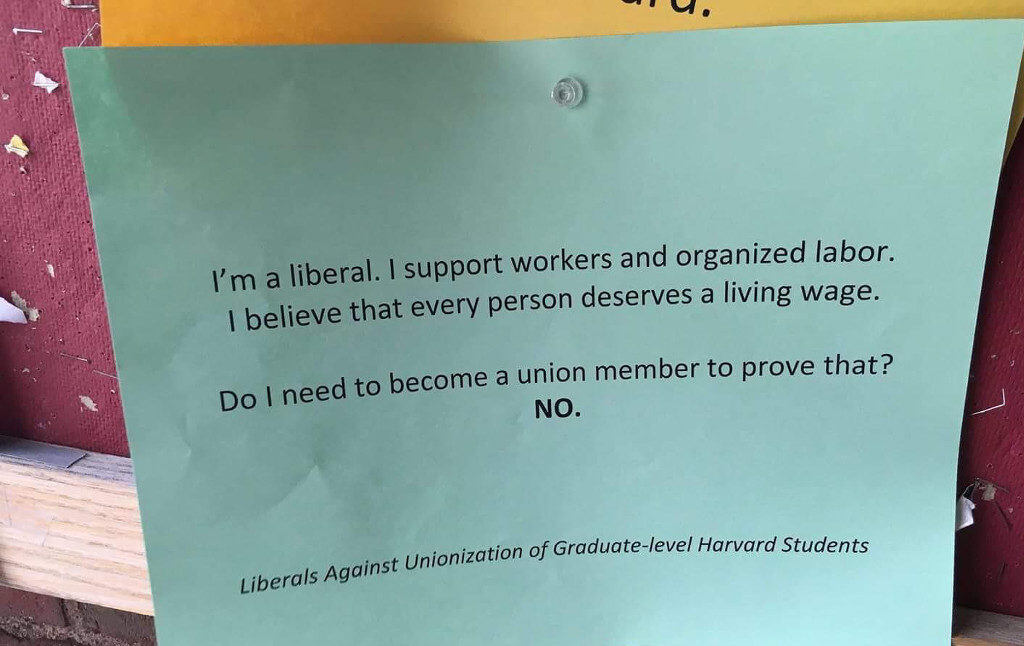

And then I see something like the above notice.

This is a sign that was posted last year, and recently recirculated on Twitter, from during the Harvard graduate students’ campaign for a union. (They ultimately won.) It is from a group called “Liberals Against Unionization of Graduate-level Harvard Students.” I don’t know if the group is real (it’s so absurd that I want to hope it’s satire, but this is Harvard, and nothing would surprise me), but the sign was definitely posted on campus. And I love it, because it really captures why leftist radicals are so often frustrated with “liberals.” The liberal sensibility is one that rhetorically affirms support for equality, but either refuses to participate in or actively opposes the social movements actually necessary to achieve that equality.

We know this has been going on for a long time, because Saul Alinsky wrote about it in 1946:

A fundamental difference between Liberals and Radicals is to be found in the issue of power. Liberals fear power or its application. They labor in confusion over the significance of power and fail to recognize that only through the achievement and constructive use of power can people better themselves… This fear of popular use of power is reflected in what has become the motto of Liberals, ‘We agree with your objectives but not with your tactics’… Every issue involving power and its use has always carried in its wake the Liberal backwash of agreeing with the objective but disagreeing with the tactics.

Isn’t it a little remarkable that the sign almost exactly repeats what Alinsky said was the liberal motto: I agree with you in principle but… I don’t support your actual campaign. It’s the same slogan that Martin Luther King heard over and over, and that moved him in exasperation to write the “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” which is all about why people who support “incremental” change are idiots who do not recognize (1) that social justice is urgent and that (2) it takes actual effort to achieve it. So a “liberal” is the person who will lament the increase in inequality, without recognizing the labor struggle that is necessary to take power away from rich owners and give it to ordinary workers. Or, during the Vietnam War era, the person who will talk about what a “tragedy” the war is while being uncomfortable with those who take to the streets to demand that it actually end. Phil Ochs’ “Love Me, I’m a Liberal” from 1964 remains an incredible song for how well it holds up. He talks about those who read the New Republic and Nation, and “love[s] Puerto Ricans and Negros / as long as they don’t move next door.”

I attend all the Pete Seeger concerts

He sure gets me singing those songs

And I’ll send all the money you ask for

But don’t ask me to come on along

“Sending the money” may sound like material support, but it’s actually the Southern Poverty Law Center model: Instead of organizing people and getting them involved, you just send a check to assuage your guilt, hoping that the Organization will then do the social justice and fix the problems. (But if you do want to do that, you can send Current Affairs money and we will solve the problems.) People get to live apolitical lives and hope that someone else out there is taking care of things. The election of Donald Trump showed that nobody was, in fact, out there taking care of things.

“I am generally fine with and even supportive of unions. Just not this one.” This was a tweet sent by Vox writer German Lopez in 2017. Two years later, in an excellent essay, Lopez explains how he learned the importance of labor organizing and has since become an organizer. He explains all the benefits of having a strong labor movement, and encourages people to organize their workplaces. Contrast this perspective with that of Jonathan Franzen, who just published an essay in the New Yorker encouraging activists pushing for a Green New Deal to give up. From a position of immense wealth and comfort, Franzen tells those who will be affected by climate change that their political movement to try to deal with it is destined to come to naught. He comes up with lots of justifications for not joining in. Phil Ochs could have written a new verse about him.

I accept scientific conclusions

There’s no one more rational than I

I harbor no right-wing delusions

The climate is going awry

But your Green New Deal’s an illusion

And your movement is destined to die

So love me, love me, love me

I’m a liberal!

This is frequently what leftists are referring to when we rant about liberals: people who want to be good but aren’t invested in the political projects that make the world better. I saw this in Steven Pinker‘s book Enlightenment Now: He’s harshly critical of “social justice warriors,” but insists he’s devoted to progressive change and sees problems in the world that need fixing. But as Jeremy Lent pointed out in his excellent reply to Pinker, you don’t get progress without progressives, people willing to fight the political battles necessary to get stuff done.

Of course, the word “liberal” has endless meanings (many radical free market capitalists describe themselves as liberals, such as Deirdre McCloskey in the new book Why Liberalism Works). Some use it to mean “people who believe in civil liberties,” and therefore suggest that today’s left don’t care about civil liberties. As Zack Beauchamp writes in his report on critics of liberalism:

For all their anti-liberal rhetoric, virtually none of today’s serious left critics of liberalism are Stalinists or Maoists — that is, opponents of democracy itself. They believe in liberal rights like freedom of expression, and pursue their revolutionary agenda through social organizing and democratic elections… Many of the sharpest left-wing critics of liberalism do not frame themselves as opponents of liberal democratic ideals. Rather, they argue that they’re the only people who can vindicate liberalism’s best promises.

The divide between the “Sanders left” and the Buttigieg center is not over civil liberties, then. It’s much more about theories of political and economic power and how that power should be redistributed.

Adam Gopnik of the New Yorker, in his new book A Thousand Small Sanities: The Moral Adventure of Liberalism, comes out strongly for the liberals. He concedes that liberalism has always been “rhetorically weak,” because it’s easier to sell people on passion than pragmatism. He says that the liberal talking to the leftist is like “a dad telling a teenage girl that she should be very careful riding in cars with other teens who drink. You sound like a schmuck compared to the cool boy who drives seat-belt-less with artfully tossed Hunter Thompson paperbacks on the backseat. But that dad is simply, invariably right.“

I have to say, when you read stuff like this, can’t you see why leftists get so goddamn mad at the liberals? I mean, Jesus, how patronizing can you get? This smugness of tone is characteristic of liberals, who refuse to take leftists seriously and talk to them precisely as Gopnik encourages them to do—like a know-it-all father lecturing his daughter about Boys.

What are Gopnik’s actual responses to the case made by the democratic socialists? Are they intelligent and compelling? They are not:

The left treats the obvious and inarguable lessons of the twentieth century about radical revolutions—lessons about the failure of revolution in the absence of free speech and open debate, of parliamentary procedures and small-scale experiments in change—as though they had never been learned and learned in the hardest of hard ways.

I’m really not sure what he’s talking about here. The DSA are for “democratic” socialism precisely because leftists recognize the potential of revolutions bringing harm instead of progress. You want parliamentary procedures? Oh boy, you should have seen the DSA convention. Unless Gopnik is arguing that Bernie Sanders is a hardcore Maoist or Marxist-Leninist, he’s wrong that “the left” hasn’t evolved since 1917. There are, to be sure, people who are skeptical of free speech and open debate, though often what this actually means is “they think a prestigious college shouldn’t invite a far-right troll to come and spew slurs at Muslim and transgender students.” But Gopnik’s liberalism is only a response to that part of the left. I am not sure why it should persuade me, or Sanders, or the DSA or any of the other parts of the left that it doesn’t describe.

He does have some other critiques, all of them pretty bad. He says that “while the new radical assault on liberalism suggests a passionate politics, it still doesn’t propose a practical politics—one that seems likely to win elections rather than impress sophomores at Sarah Lawrence.” It’s rather stunning that Gopnik has the audacity to say this in 2019, when there is a very strong argument that (1) Bernie Sanders would have beaten Donald Trump in 2016 and (2) Bernie Sanders is the best candidate to beat Donald Trump in 2020. Socialists are beginning to win elected office across the country. Of course, a political movement isn’t built overnight, but I don’t know how Gopnik can present liberalism as having broad popular appeal when Democratic representation in elected office collapsed so badly under Barack Obama. (It would also seem to conflict with his earlier idea that liberalism is a tough sell because people are easily motivated by passion.)

Here’s another of his critiques, this time of the leftist argument that capitalism is causing climate change:

[E]conomic issues peculiar to capitalism have to be separated from those pervasive in modernity. When, for instance, contemporary leftists treat the environmental disasters that frighten us all as capitalism’s war against the planet—or worse, neoliberalism’s war against the planet—they are engaged in a campaign that is, from a historical point of view, absurd. Environmental disasters are the right thing to be worried about, but it is the drive for growth, not capitalism in particular, that makes them happen. The degree and level of environmental disaster caused by the command economics of Eastern Europe were far greater than even the worst known in Western Europe and was made still worse by a state-controlled media that could not even wave a feeble flag of dissent… The villain in our environmental disasters may well be the common fault of modernity and of industrialization. But to understand pollution as a problem owed to capitalism is to understand nothing.

Here, Gopnik is full Smug Lecturing Dad mode, even as he makes an elementary error of reasoning. Here is the Gopnickian sequence:

- People say that capitalism causes environmental destruction.

- Environmental destruction also occurred in the Soviet Union, which was not capitalism.

- Therefore capitalism does not cause environmental destruction.

Which is like saying:

- People say that smoking causes cancer.

- But asbestos causes cancer, and asbestos is not smoking.

- Therefore smoking does not cause cancer.

And he has the audacity to treat leftists like children! Perhaps he is right that “the drive for growth” is what causes environmental destruction. And perhaps the Soviet Union also had a drive for growth. (Just like there could be some feature that cigarettes and asbestos have in common.) But what this proves is that capitalism isn’t the only way to destroy the environment, not that environmental destruction is not caused by capitalism. (I apologize for the double negative.) If the “drive for growth” is an essential feature of capitalism (which it very well may be), then it could be that you can’t have capitalism without environmental destruction! And many defenders of capitalism say that its ceaseless drive for growth is one of its best features!

How can the left not be mad at the liberals? With Pinker, I pointed out that one of the most annoying things in the world is when someone loudly declares themselves to be Reasonable even as they are being objectively unreasonable. Gopnik talks down to the left about the importance of civil liberties and the record of the Soviet Union, even while failing to engage the substance of left arguments, and providing no compelling response to Bernie Sanders’ agenda on climate change.

I am sorry, but if we’re going to solve giant political challenges, we’re going to need fewer of these types, the ones who say “I am for unions, just not this one,” and “I’m for your goal but against your tactics,” and “I am the adult who understands politics while you are the child who doesn’t.” The ones who motivated Phil Ochs to sit down and angrily write:

The people of old Mississippi

Should all hang their heads in shame

I can’t understand how their minds work

What’s the matter don’t they watch Les Crane?

But if you ask me to bus my children

I hope the cops take down your name

So love me, love me, love me, I’m a liberal

Update: The sign was indeed likely satire by wry leftists. (See what the group’s initials spell.) Gopnik’s book, however, is definitely not. And when the Harvard graduate student organizing drive was taking place, I met plenty of fellow grad students who said exactly what was on that sign: We need unions, but not here. The union won its vote, but hundreds of grad students voted against it, and I guarantee the majority of them were Democrats, just like the Harvard administration and president who fought hard against the union, and the professors who sat on the sidelines and declined to offer support.