The Southern Poverty Law Center Is Everything That’s Wrong With Liberalism

The SPLC’s deceptive and hypocritical approach to anti-racism…

The Southern Poverty Law Center, the wealthiest civil rights organization in the country, has ousted its founder, Morris Dees, and president, Richard Cohen, amid unspecified allegations of workplace misconduct by Dees. Dees had been with the organization since creating it in 1971, while Cohen had joined in the mid-’80s, and the SPLC’s shake-up can be seen as part of the MeToo reckoning in which conduct that was accepted for years is finally being dealt with appropriately.

But the organization has long been dysfunctional in even deeper ways, and the story of Dees and the SPLC is useful for illustrating some of the worst and most hypocritical tendencies in American liberalism. If we understand the full extent of what went wrong in this organization, we’ll better understand the ways in which a shallow “politics of spectacle” can take hold, and see the kinds of practices that need to be categorically rejected in the pursuit of progressive change.

The Southern Poverty Law Center perfectly shows social change done wrong. It was a top-down organization controlled by an incompetent and venal leadership.* It was hypocritical in the extreme, preaching anti-racism while fostering a racist internal culture and being led by men whose own commitment to equality was questionable. It didn’t care about listening to and incorporating the viewpoints of the people it was supposed to serve. It was obscenely rich in a time of terrible poverty, and squandered much of its considerable wealth. Finally, it picked the wrong political targets, and focused on symbolic over substantive change. Each of these practices goes beyond the SPLC, and is endemic to a certain kind of “elite liberalism” that desires “progress” without sacrifice. It is the kind of liberalism recognized by Phil Ochs in 1966, and its chief characteristics are a deep hypocrisy and a lack of willingness to seriously challenge the status quo.

Deploring Bigotry While Engaging In It

In a recent exposé of his time at the SPLC, Bob Moser explains how strange it felt to arrive at a civil rights organization and notice a sharp internal racial hierarchy:

[N]othing was more uncomfortable than the racial dynamic that quickly became apparent: a fair number of what was then about a hundred employees were African-American, but almost all of them were administrative and support staff—“the help,” one of my black colleagues said pointedly. The “professional staff”—the lawyers, researchers, educators, public-relations officers, and fund-raisers—were almost exclusively white.

The situation Moser observed existed for decades. A 1994 Montgomery Advertiser report on the center confirmed that “no blacks have held top management positions in the center’s 23-year history, and some former employees say blacks are treated like second-class citizens.” Nor did the SPLC change course after that exposé. Apparently “there were sporadic pledges to try to address these inequities, but they persisted” and a former board member said she did not recall “any concrete steps that the board took to address” workplace racial disparities. In 2013 the composition of the organization’s leadership was still blindingly white.

The Advertiser quoted black Harvard Law School graduate Christine Lee, who interned there, saying “I would definitely say there was not a single black employee with whom I spoke who was happy to be working there. Of 13 black former employees the Advertiser contacted, 12 had said they “either experienced or observed racial problems inside the law center… Three said they heard racial slurs, three likened the center to a plantation and two said they had been treated better at predominantly white corporate law firms.” Dana Vickers Shelley, formerly one of the highest-ranking black employees at the center, commented that “They weren’t even trying to be diverse in terms of reflecting the people who they served.”

Some of the racism was egregious. A paralegal heard Dees comment of black women that “I like chocolate.” When a black employee, Dana Vickers Shelley, left the organization, president Richard Cohen asked her what her subordinate, also a black woman, intended to do next. Ms. Shelley said she didn’t know. Cohen’s reply shocked her: “His response to me that I will never forget was, ‘Well, the 13th Amendment says she can do whatever she wants.’” Former employees have reported that “racially callous remarks at the center were not uncommon, and that professional voices of people of color were often sidelined, affecting the center’s work and priorities.”

Dees, in defending the lack of high-ranking black staff, said the following:

“We don’t have black slots and white slots… Probably the most discriminated people in America today are white men when it comes to jobs… It is not easy to find black lawyers. Any organization can tell you that.”

Martin Luther King was famously skeptical of those white people who insisted they supported the goals of the civil rights movement, but stood in the way of actually achieving those goals. His Letter From Birmingham Jail comments that “shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will.” On the charitable assumption that Morris Dees was a “person of good will,” he was exactly the kind of person who stands in the way of achieving racial justice. He made his living talking about racial injustice, yet paid zero attention to the racial injustice that he himself was presiding over every day in the workplace.

Caring About Equality Except In The Workplace

The “workplace blindspot” is common among wealthy liberals. I can’t tell you how many friends I’ve talked to who have worked at “progressive” nonprofits that mistreated and exploited their employees. The boss at a women’s rights nonprofit does not notice that they are cruelly bullying women every day, or the head of a pro-labor organization demands absurd hours from their workers. This is why “workplace democracy” is such an important left demand. It’s a call to take the values of equality seriously, to actually implement them in every sphere of life.

At the Southern Poverty Law Center, Morris Dees was a monarch. He “call[ed] all the shots” and was “head of the show.” A former legal director said that during his tenure, “all the people on the board were people [Dees had] picked, he was boss of the office; there wasn’t really anybody who could fire him…” The board of directors, who are supposed to hold a nonprofit’s executives to account “seemed like a shadow board,” and could “pretty much… be counted on to vote however it is Morris recommends they vote.”

So when there were allegations of misconduct against Dees, they didn’t go anywhere for a long time. Instead, after SPLC president Richard Cohen “had been told of at least one allegation against Mr. Dees,” he simply “ordered the removal of an exit-interview question about workplace culture.” If you don’t ask about workplace culture, you won’t have messy allegations to deal with.

A nonprofit organization should of course be run democratically, with people affected by decisions having a chance to participate in them. When an organization is a kingdom, the king can get away with harassing and abusing people. It doesn’t matter whether what that organization is doing is good, if it’s internally undermining the very values that it is ostensibly promoting.

Being Obscenely Rich In A Time Of Need

Morris Dees began his career as a direct-mail marketer, selling “doormats, tractor seat cushions, and cookbooks.” His former business partner recalled that “Morris and I … shared the overriding purpose of making a lot of money. We were not particular about how we did it; we just wanted to be independently rich.” Dees even “earned cash by doing some legal work for the Ku Klux Klan.” Dees was so successful at selling products through the mail that he eventually made it into the Direct Marketers Hall of Fame. (Yes, postal spammers have a hall of fame, apparently.) Dees didn’t change his methods: “We just run our business like a business,” he said. “Whether you’re selling cakes or causes, it’s all the same.”

Dees was as successful at selling causes as he had been at selling cakes. Fueled by Dees’ direct mail campaigns, the Southern Poverty Law Center brought in million after million. Last year it took in $136 million, and it now sits upon an endowment of nearly half a billion dollars. Yet even after some within the organization thought it should stop raising money, and despite promises by Dees that it would do so, its fundraising pitches in the mail became ever more desperate and frantic. A 1995 pitch, sent when the SPLC was sitting on more than $60 million in reserves, told potential donors that the “strain on our current operating budget is the greatest in our 25-year history.” All sorts of tricks were tried, and a former Dees associate reported that the organization once used about six different low-value stamps on envelopes, to give the appearance that it could barely afford to cobble together 35 cents of postage.

(Sometimes all of this became downright grotesque. In the 1980s the SPLC sued the Klan over the lynching of Michael Donald, and won a $7 million verdict for Donald’s mother. The Klan, however, had by this time diminished to almost nonexistence. Its sole asset was a warehouse that was sold for $55,000, which was all Donald’s mother got. She apparently used a large portion of this to pay back an interest-free loan that the SPLC itself had extended her. Afterward, the SPLC began using photos of Michael Donald’s corpse in its fundraising letters, raising $9 million off the case. Donald’s mother evidently saw none of this money, though when she died barely a year later Morris Dees was quoted in her obituary praising her bravery.)

Yet the SPLC has been criticized for decades for doing very little with its vast resources. It spent less than a third of the money it took in on its programs. (The NAACP, by contrast, spent nearly everything it took in. So did the Southern Center For Human Rights.) A death penalty lawyer who collaborated with the center said: “I was naive at first… I thought the Southern Poverty Law Center raised money to do good for poor people, not simply to accumulate wealth.” The SPLC did spend $15 million on its current office building, a 150,000 square foot behemoth designed by a New York architecture firm and dubbed the “Poverty Palace.” Dees and Cohen also earned over $300,000 a year each. But the tragedy of the SPLC has long been that there is so much it could be spending its money on and isn’t.

This is not to say that there is no good work done by the SPLC. There is a lot. If you hire dynamic young public interest attorneys at decent salaries, they’ll likely pursue some worthwhile cases. The SPLC annual report contains some encouraging accounts of great things the Center has done. It has an immigrant justice initiative that “enlists and trains volunteer lawyers to provide free legal representation to detained immigrants facing deportation proceedings in the Southeast.” On the criminal side it “filed suit in state court, accusing Louisiana of failing to establish an effective statewide public defender system” and sued cities that detained people over unpaid debt. The SPLC could run through a very long list of its admirable legal triumphs. But it’s important to consider these in the context of the organization’s giant fundraising hauls. The SPLC is bringing in over $360,000 every day and only spending a fraction of it on its legal work.

In fact, Dees never even wanted to run a poverty law firm. In a 1988 article in The Progressive, he was explicit: “We’re not a public interest law firm, not a legal aid society taking any case that comes in off the street. We only want the precedent-setting cases… Maybe our name is part of the problem.” But the United States is in need of more public interest law firms! The kind of representation poor people receive in criminal cases is often horrendous, and legal aid is woefully underfunded. Many of the SPLC’s donors surely think they’re donating to a public interest law firm. In fact, they’re mostly donating to an ever-growing giant pile of money, a portion of which is used to finance some progressive legal work.

The SPLC’s misuse of money is outrageous. Think of all the good it could have done with its millions and hasn’t done. But here, again, we see a frustrating tendency in liberalism: not appreciating what money could do for people if used well, and not seeing how revolting it is to hoard wealth in a time of extreme need.

Focusing On The Wrong Thing

What the SPLC doesn’t do with its money is a problem. But there is also a problem with what it does do. The story here has been told many times: After beginning as something vaguely resembling a “poverty law” firm in the ’70s, and winning a number of important anti-discrimination fights, the SPLC turned much of its attention to going after “hate groups.” It pursued the Ku Klux Klan in court on behalf of its victims, winning large judgments. Over time, it began to track “hate” across the country, and it now has a 15-person staff producing “intelligence reports” on hate groups.

The SPLC’s shift toward focusing on hate groups was controversial within the organization. Some felt that it would make sense to focus on more systemic problems, like mass incarceration, rather than targeting (usually small) far-right fringe groups. But Dees saw an opportunity for both publicity and fundraising, and he was right. The organization mostly stopped taking death penalty cases (too controversial with donors) and instead focused on neo-Nazis, a group that pretty much everyone despises.

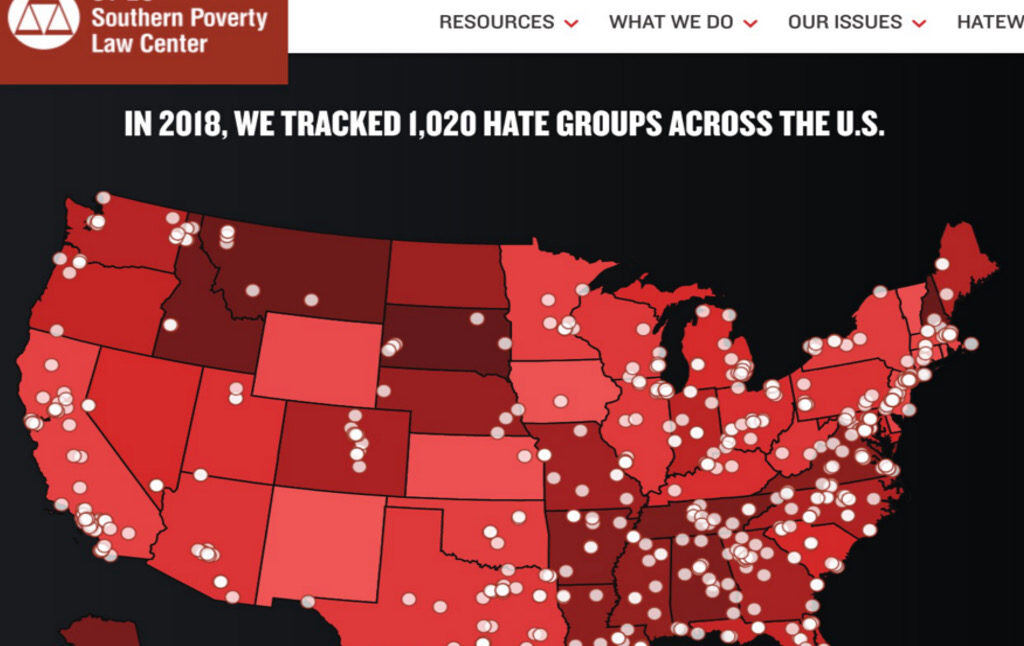

The SPLC devotes a phenomenal amount of effort to chronicling “hate” across the country. Its quarterly “Intelligence Report,” a beautifully-produced glossy magazine about hate groups, is mailed out by the hundreds of thousands. It writes long profiles of hate figures documenting their every bigoted utterance, and keeps tabs on hate groups through its signature “Hate Map.”

There has long been controversy over the SPLC’s “hate watch” activities. Conservatives are constantly complaining that they have been unfairly labeled racists, with mainstream conservative organizations like the Family Research Council landing themselves on the SPLC list. When Maajid Nawaz, a controversial critic of Islamism, was labeled an anti-Muslim extremist by the SPLC, he sued and received a $3 million settlement, plus an apology. One problem here is that the definition of “hate” is very unclear. It supposedly means having “beliefs or practices that attack or malign an entire class of people,” but in that case I’m a member of a hate group myself, since I despise bourgeois liberals. The SPLC includes “black nationalism” on its list of hate categories, which means that every time it reports the number of hate groups in America it is including the “New Black Panther Party” (and doing precisely what FOX News did in its own disgraceful reporting on the supposed threat posed by roving gangs of New Black Panthers).

The biggest problem with the hate map, though, is that it’s an outright fraud. I don’t use that term casually. I mean, the whole thing is a willful deception designed to scare older liberals into writing checks to the SPLC. The SPLC reported this year that the number of hate groups in the country is at a “record high,” that it is the “fourth straight year” of hate group growth, and that this growth coincides with Donald Trump’s rise to power. There are now a whopping 1,020 hate groups around the country. America is teeming with hate.

Let’s dig into this number a bit. The first thing you should note is that it’s meaningless. The SPLC consistently declines to identify how many members these hate groups have. It just notes the number of groups. Without knowing how large they are, what does it mean that they exist? Are they one person? 1000? Hypothetically, the number of hate groups could be dropping while the number of people in hate groups was actually rising—say, for instance, small organizations were consolidating into a large, powerful national organization. Or it could be the other way around: The number of hate groups could be increasing because the neo-Nazis were becoming weak and fragmented and splitting into tinier and tinier units.

In fact, when you actually look at the hate map, you find something interesting: Many of these “groups” barely seem to exist at all. A “Holocaust denial” group in Kerrville, Texas called “carolynyeager.net” appears to just be a woman called Carolyn Yeager. A “male supremacy” group called Return of Kings is apparently just a blog published by pick-up artist Roosh V and a couple of his friends, and the most recent post is an announcement from six months ago that the project was on indefinite hiatus. Tony Alamo, the abusive cult leader of “Tony Alamo Christian Ministries,” died in prison in 2017. (Though his ministry’s website still promotes “Tony Alamo’s Unreleased Beatles Album.”) A “black nationalist” group in Atlanta called “Luxor Couture” appears to be an African fashion boutique. “Sharkhunters International” is one guy who really likes U-boats and takes small groups of sad Nazis on tours to see ruins and relics. And good luck finding out much about the “Samanta Roy Institute of Science and Technology,” which—if it is currently operative at all—is a tiny anti-Catholic cult based in Shawano, Wisconsin.

Even when the groups are functional, they’re mostly pitiful. A Portland group called the Hell Shaking Street Preachers tried showing up to the local pride parade and simply got laughed at and glitter-bombed. The websites mostly look like they haven’t been updated since the Geocities days. (See, for example, the masterpiece design job on The Divine International Church Of The Web.) The “Wotan’s Nation” site still has its Lorem Ipsum text. I did stumble across one group, a terrifying-looking neo-Nazi biker gang called the Aryan Nations Sadistic Souls, who were definitely serious racists and looked as if they were probably up to no good. But in the “events” listed on their website, it seems they mostly get together for canoeing trips and pool parties. Here are the Nazis on the march:

The SPLC doesn’t actually link to or provide details about many of the groups it profiles, perhaps because this would reveal what a joke many of them are. When it does dive deeper, the results are often predictably comical. The Georgia map lists something called “Wildman’s Civil War Surplus and Herb Shop” as a “hate group.” The SPLC evidently sent a reporter to Kennesaw to investigate the group, which turns out to consist entirely of a bearded old bigot who runs a Confederate memorabilia shop. The Center ran a full profile of the man, with the headline “RACIST KENNESAW, GA. SHOP OWNER EMBRACED BY COMMUNITY.” How, exactly, was he “embraced by the community”? Here is the sum total of the evidence:

In 1993, the Kennesaw Historical Society awarded him its first Historic Preservation Award, a fact noted on the society’s website (although there’s nothing there about his racism). In 2002, Myers appeared as Clara’s uncle in a performance of “The Nutcracker, Kennesaw Style.”

My God, the whole Kennesaw community has embraced hate. They gave a Confederate sympathizer a historic preservation award in 1993! And as recently as 17 years ago, they let him have a supporting role in a community theater production of The Nutcracker!

This whole SPLC set-up strikes me as fraudulent in the extreme. I don’t know how else to describe it. They have a team of people investigating these groups. They have to know that they’re inflating the danger. They know that when they report “over 1,000” hate groups in America, they’ve deliberately excluded membership numbers in order to sound as scary as possible. They’re perpetrating a deception, because they don’t want you to know that groups like the “Asatru Folk Assembly” are no political threat. The SPLC has continuously sent out terrifying lies to make old people part with their money. They’ve become fantastically wealthy from telling people that individual kooks in Kennesaw are “hate groups” on the march. And they’ve done far less with the money they receive than any other comparable civil rights group will do. To me, this is a scam bordering on criminal mail fraud. If you tell people things that aren’t true so that you can take their money and then not use that money for the thing you said you would use it for, you’re a fraudster. I hestitate to say that because I know lots of great people who have worked at the SPLC, and good work is done there. But the Morris Dees model is a scam: It finds as much “hate” as possible in order to make as much money as possible.

If you trawl through the Hate Map for a little while like I did, you may also feel uncomfortable for another reason. Most of the people they’re listing as threats seem as if they are poor and unschooled. I bet if you compared the average annual salary of the SPLC staff to the average salary of the people in these hate groups, you’d find a massive class divide. Whether it’s poor Black people joining weird sects like the United Nuwaupians, or poor white people getting together and calling themselves things like the “Folkgard of Holda & Odin,” these are people on society’s margins. A lot of this seems to be educated liberals having contempt for and fear of angry rednecks.

This is not to say that neo-Nazis aren’t fucking terrifying, or that they don’t pose any threat. The Daily Stormer is a real thing, and there is a lot of dangerous white supremacist nonsense believed by a lot of people. But the “hate” focus is all wrong: The biggest threats to people of color do not come from those who “hate” them, but from those (like the contemporary Republican Party) who are totally indifferent to whether they live or die. This is the frightening thing about contemporary racism: It does not come waving the Confederate flag, it comes waving the American flag.

Alexander Cockburn, in a stinging critique of the SPLC, once posed a challenge to Morris Dees:

Why is Dees fingering militiamen in a potato field in Idaho when we have identifiable, well-organized groups that the SPLC could take on? To cite reports from United for a Fair Economy, minorities are more than three times as likely to hold high-cost subprime loans, foisted on them by predatory lenders, meaning the big banks; all black and Latino subprime borrowers “could stand to lose between $164 billion and $213 billion for loans taken during the past eight years.” Get those bankers and big mortgage touts into court, chief trial counsel Dees! How about helping workers fired by people who hate anyone trying to organize a union? What about defending immigrants rounded up in ICE raids? How about attacking the roots of Southern poverty, and the system that sustains that poverty as expressed in the endless prisons and death rows across the South, disproportionately crammed with blacks and Hispanics?

Cockburn’s questions are still unanswered. But the SPLC are not the only one who should have to confront them. The Southern Poverty Law Center has long demonstrated tendencies that are common to American liberalism: hoarding wealth that could be used to fix things, condemning inequality while perpetuating it, and focusing on individual hatemongers rather than systemic injustices. While the SPLC has gotten better in recent years about taking on some important impact litigation, the whole “hate” framework is politically misguided. The haters are often the powerless rather than the powerful, because the powerful have no reason to be angry. The United States isn’t overrun by skinheads, it’s overrun by greedy sociopathic plutocrats who could not give a shit about Black children in crumbling Detroit schools or the global victims of climate change. Reading the SPLC “Intelligence Report” will give you a totally skewed idea of how racism works and how to begin solving it. It’s not going to be fixed when biker gangs stop doing heil salutes at their picnics. It will be fixed when Black women aren’t dying in childbirth, having a Black-sounding name doesn’t hurt you on the job market, the wealth gap is closed, and both social microaggressions and economic macroaggressions are vanquished for good. The SPLC is right that we’re a long way from justice. But their way of thinking won’t get us any closer to it.

In Alexander Cockburn’s article about the SPLC, he recommended that instead of donating to them, you consider donating to the Southern Center For Human Rights, an organization that does important legal work on behalf of the poor, and that is transparent and uses its money extremely frugally. I used to work for Stephen Bright, the founder of the SCHR (and a longtime Dees critic), and can confirm that he was the most honorable and empathetic person I have ever met, and the organization is a paragon of integrity. So I second Cockburn’s recommendation and encourage you to consider supporting them.

In writing this piece I relied on the excellent investigative reporting on the SPLC by Ken Silverstein of Harpers, John Egerton of the Progressive, and the Montgomery Advertiser, as well as the The New Yorker and New York Times reports.

*I realize that I am saying “was” even though the SPLC still exists. I’m using the past tense because hopefully the post-Dees SPLC will be a very different organization, and the incarnation of the SPLC that has been criticized for so long will finally cease to exist.