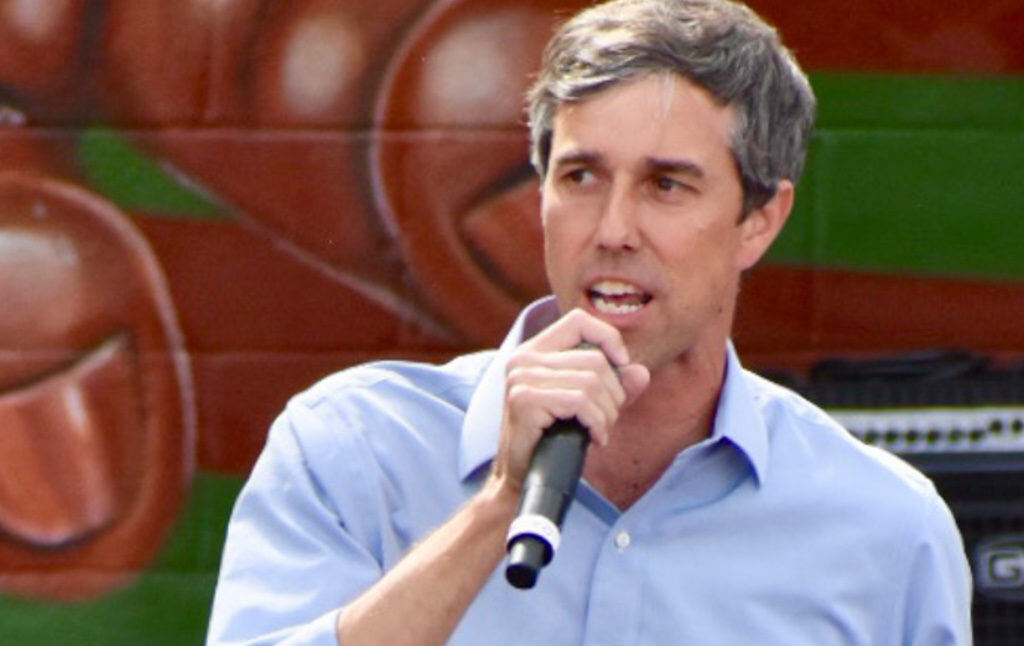

What Does Beto O’Rourke Actually Stand For?

What makes anyone think O’Rourke should be president? He is neither a bold progressive nor a distinguished legislator.

Beto O’Rourke—a three-term Congressman from El Paso, Texas who recently failed to unseat Texas Republican Senator Ted Cruz—is suddenly one of the hottest names in Democratic Party politics. The once-obscure representative is on the lips of many as a presidential contender. “All the guy would have to do is send out an email to his fundraising base…and he raises $30 million,” one anonymous Democratic bundler told Politico. “That has totally changed the landscape for tier 1 guys, because now Bernie and Warren, now they have competition. It completely changes the game if Beto runs. And he should run…He’s Barack Obama, but white.”

Former Obama adviser Dan Pfeiffer made a slightly less cringeworthy version of the same argument, arguing that he has “never seen a Senate candidate—including Obama in 2004—inspire the sort of enthusiasm Beto did in this race. This is about more than Lebron wearing a Beto hat, or Beyonce sporting one on Instagram. It’s about the people all over the country with no connection to Texas with signs in their yards and sticker in their cars.” He concluded that “millions of people already believe in Beto O’Rourke, and that moment, for them and him, may be upon us.” O’Rourke himself fueled these fires by recently reversing himself on a pledge not to run for president, telling a town hall audience, many of whom wanted to see him pursue the presidency, he will think about what he will do next.

But it’s not just a few donors and Democratic strategists uniting behind a potential Beto bid. A significant number of Democratic voters, too, have embraced Beto-mania. As Pfeiffer noted, there is indeed a measurable grassroots swell behind O’Rourke. One recent national Politico poll named him as third among potential Democratic Party presidential nominees. A recent You Gov/U Mass 2020 poll found O’Rourke netting 10 percent of Massachussetts Democratic voters, just a single point behind the state’s own senator, the populist liberal Elizabeth Warren. These voters, many of them likely liberal in political orientation, are matched in their enthusiasm for O’Rourke by some of the party’s most reactionary elements.

“He’s game changing,” Robert Wolf, a former top executive at the UBS investment bank and Democratic mega-donor known to raise Wall Street cash for candidates, told Politico. “If he decides to run, he will be in the top five. You can’t deny the electricity and excitement around the guy.”

“We are big Beto fans,” the Clintonite think tank Third Way’s Matt Bennett told NBC during his Senate run. “He’s not with us on every single thing, but his main campaign themes have been very close to what we think a national narrative should be. And the happy warrior approach is just right for running against a horrible person like Cruz or Trump.”

Having spent nearly a decade reporting on American politics, I can say there is something very odd about “Beto-mania.” Typically, politicians have both elite friends and enemies, meaning donors, activist organizations, lawmakers, and pundits, within their own political party. O’Rourke has critics in the GOP—they successfully defeated him in Texas’s Senate race. But he should presumably also have critics within the elite functionaries in the Democratic Party as well. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders both have their elite critics across the political spectrum. The former is loathed by Wall Street, the latter is loathed by pretty much everyone who runs a Democratic-aligned think tank or has a rolodex of party mega-donors.

But O’Rourke, on the other hand, seems to have received nothing but praise from everyone from Wall Street donors like Wolf to Obama alumni like Pfeiffer to a large liberal following enamored by his skateboarding at Whataburger and his passionate defense of kneeling NFL players. He has become a uniting figure for Democrats, beloved by all and loathed by none. What kind of Democratic politician can be so adored?

Maybe one who rarely, if ever, challenged the powerful.

Representing a Left-Wing District But Embracing New Democrat Politics

There is no doubt that O’Rourke is a talented politician. His $60 million haul, much of it from small donors, came from extremely aggressive campaigning all over the state of Texas, alongside a national donor base cultivated by signaling to culturally liberal activists. But a talented politician is not necessarily someone who has talent in governing. So what was Congressman O’Rourke like?

In his six years in Congress, O’Rourke passed three bills. Two were related to veterans issues, the third renamed a federal building and courthouse. Of course, O’Rourke was in a GOP-dominated House, which would limit his effectiveness. But part of being effective as a Member of Congress is learning to deal with the environment you are in. Between 1995 and 2007, when the Republicans solidly held the House of Representatives, the lawmaker who passed the most amendments was not a far-right Republican but instead Vermont’s independent democratic socialist Bernie Sanders, dubbed an “amendment king.” The firebrand Florida Democrat Alan Grayson was similarly effective at writing and passing legislation.

But even if you’re not passing bills or amendments, you can chair investigations and help uncover important information that changes the debate in Washington. You can earn media appearances and become a leader on major issues. You can help move legislation that isn’t going to pass anytime soon, but set it up for the future.

O’Rourke was missing in action on virtually all of these areas, and rarely challenged concentrated power in D.C.—except during his initial run for Congress, in which he unseated a conservative Democrat Silvestre Reyes. Reyes was a proponent of America’s drug war while O’Rourke favored legalizing marijuana to cut into the cartels’ power. Reyes ran dirty campaign ads claiming O’Rourke was encouraging drug use among children. It didn’t work, and O’Rourke’s smart campaign was victorious.

But it may have been the last time O’Rourke waged a sustained campaign against the Democratic establishment. While the Democratic base is coalescing around single-payer health care and free college, O’Rourke sponsored neither House bill. During his time in Congress, he never joined the Congressional Progressive Caucus. He has been, however, a member of the New Democratic Caucus, the group organized to carry on the ideas of Clintonite policies. During the 2016 presidential primary, he stayed on the sidelines.

If you’re not familiar with O’Rourke’s district, you might chalk this all up to representing a conservative region. It’s Texas, right? Our system is a representative democracy with single member districts, and lawmakers must represent politically diverse constituencies. Otherwise, they risk being thrown out. But Texas’s 16th Congressional District is among the more liberal in the country. In 2016, O’Rourke netted 85 percent of the vote, while a Libertarian grabbed 10 percent and a Green received 4 percent. There was no Republican candidate. To be fair to O’Rourke, the 2014 election, a terrible year nationwide for Democrats, was more risky for the congressman—that year he received only 67.5 percent of the vote.

While O’Rourke steadily avoided left-wing legislation, he went above and beyond to ally himself to the corporate wing of the Democratic Party. In 2015, Congress narrowly gave President Obama so-called “Fast Track” authority as it related to the Trans-Pacific Partnership. This essentially greased the skids for Obama to accept and implement this agreement, which many labor, consumer, human rights, and environmental advocates worried would vastly expand the power of investors and corporations and undermine U.S. sovereignty. The 219 to 211 vote in the House sent shockwaves through this community, and a foreboding sense that the TPP would become a reality (at that point, no one expected Donald J. Trump to be the President soon and deep six the TPP, but politics got really weird over the next few years).

O’Rourke was one of the Democrats who voted to grant the authority to Obama. His argument in favor of the agreement was that of any boilerplate free trader: “I have ultimately decided that the TPA bill lays out some really strong goals and objectives for the president to negotiate with our trading partners to open markets up for our exports, which is good for our economy and could potentially be really good for jobs in El Paso.” The exports argument was weak at best. America already maintained free trade agreements with a majority of TPP countries. What populists like Warren and Sanders feared most about the TPP was its vast expansion of patent and copyright protections—which could lock in arduous high drug prices, among other things. Regardless, O’Rourke continues to be a defender of these sorts of agreements. During his Senate run, the local press noted that he and Cruz essentially agreed on the merits of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

O’Rourke Learns to Love Israel

We can learn a lot about why O’Rourke doesn’t challenge the powerful by looking at the one time he did, briefly. In the summer of 2014, the Israeli military and militants in Gaza were engaged in prolonged warfare. Almost all of the suffering was falling on the Palestinians, whose small arms and improvised rockets were no match for the modern might of the Israeli army. This might is subsidized by the American taxpayer, who delivers billions of dollars of aid to Israel on an annual basis.

During the conflict, Congress voted to provide funds to re-supply Israel’s Iron Dome system, which helps protect it against projectile attacks. But there is no reason why Israel itself cannot provide the funds to protect its citizenry during conflicts that keep occurring partly because it refuses to respect the human rights of Palestinians—and America stepping in to pick up the tab essentially shields Israelis from one of the financial costs of maintaining their occupation.

O’Rourke was one of eight Members of Congress to oppose the Iron Dome funding, a group that was equally split along bipartisan lines. “I could not in good conscience vote for borrowing $225 million more to send to Israel, without debate and without discussion, in the midst of a war that has cost more than a thousand civilian lives already, too many of them children,” he wrote defending his vote. It was a defiant act, and for once, Congressman O’Rourke was willing to stand almost alone in the face of a powerful political force, America’s pro-Israel lobby.

But that bravery did not last long. Pro-Israel activists, including one of O’Rourke’s top donors, denounced him in the local press. Others reached out to him privately to encourage him to return to the pro-Israel consensus. And he returned quickly. He enthusiastically voted for all future aid to Israel, and courted the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC).

“He’s a good guy, but he didn’t know how the Jewish community would react,” Daniel Cheifec, executive director of the Jewish Federation of El Paso, told the Forward. “Now he knows that this community is not going to be very happy if he screws up again.” By Cheifec’s definition, O’Rourke certainly hasn’t screwed up since. He didn’t even co-sponsor meager legislation introduced by a handful of progressive House Democrats that would bar aid to Israeli units who abuse children. (Massachusetts’ Seth Moulton, who has been a vigorous advocate for the finance and national security hawk wing of the Democrats, is a sponsor).

The Progressively Less Progressive Senate Candidate Who Defeated a Berniecrat

Much to the alarm of humanist political activists like myself, the Democratic Party has increasingly embraced sectarian politics, particularly by fetishizing racial and gender labels as it chooses candidates. Yet the same Democratic Party that used these sort of attacks to sink Bernie Sanders in 2016 rallied early behind Beto O’Rourke, a straight white man, even when he faced a young Latina opponent.

You probably don’t know the name Sema Hernandez. (She may not even know how to skateboard.) But the 32-year-old Houston activist and self-described “Berniecrat” netted 24 percent in Texas’s Democratic Senate primary, despite raising less than $10,000 to O’Rourke’s $9 million.

Hernandez is the child of immigrants, a first-generation Mexican American who struggles to afford healthcare and ran her campaign on a shoestring budget. O’Rourke, on the other hand, was born into a wealthy Texas political family, attended Columbia University, and has a business background in Internet start-ups. (O’Rourke’s criminal charges in his 20s may also be relevant: The son of a judge and county commissioner, he was not prosecuted for an incident in which allegedly fled the scene of a drunken crash. There is no evidence that his father actually intervened, but the justice system has a tendency to give wealthy white Ivy Leaguers second chances that others do not get.) He is married to the daughter of billionaire real estate developer William D. Sanders (“the richest man in El Paso”)—whose development plan in downtown El Paso O’Rourke vigorously championed, against the protests of many local residents. During his run for Senate, his disclosures showed that O’Rourke’s assets are somewhere in the range of $3.5 to $16 million, thanks to rental and commercial real estate as well as his wife’s trust fund.

O’Rourke’s wealth and connections helped him crush Hernandez (except in poorer, heavily Mexican American districts in South Texas, which Hernandez won). The national Democratic party and even progressive media outlets ignored her. O’Rourke essentially treated her as a nuisance, refusing to debate her, and Hernandez reports that when she met with him after the primary, he refused to make commitments on important progressive issues. Hernandez’s account of their meeting should be read by any member of the left who considers O’Rourke a reliable ally:

SH: He kept staring at me with his hand to his chin. I told him, “How do you expect people to vote for you, if you vote against us? If you vote for a seven hundred billion dollar military budget that is not earmarked for Vets? When that money could have been used for Medicare for all or college for all or a list of other things.” I mentioned I didn’t like how he followed the DCCC script on Medicare for all. He countered that he does not follow Party lines. He took offense and explained why he did not sign on to H.R. 676 because private health care would not get paid. I asked him to cosponsor H.R. 676 even if he doesn’t think it will pass. It’s a show of good faith and support for Medicare for all. He told me that he was not going to sign H.R. 676 just because it is what people want or because it is popular…. I asked him to explain why he was running, why he got into the race. I don’t have healthcare. I do not have a good paying job. Our families and our communities are impacted more than he is.

Interviewer: What did he say?

SH: He said he is running because he believes every Texan and person in the USA deserves affordable healthcare, schooling, and ways to support their family. I expected a candid response and I got his campaign speech. I wanted to get to know him as a person and instead I got what you see on television, a politician. I treated him with respect, I was honest and blunt. After all of that I wanted more.

Unlike O’Rourke, Hernandez ran on an unflinching support for the Sanders platform of universal college and higher education. O’Rourke’s support for similar politics was, like his opposition to needlessly funding the Israeli military, fleeting. When he first announced his Senate run, he said we “need a single-payer healthcare system for all Americans.” As his campaign progressed, his language on healthcare did, too. A year after O’Rourke said we need single-payer, Politico noted that the congressman slyly changed his wording on health care issues. He stopped using the phrases Medicare for All or single-payer, and instead would tell crowds we need “universal, guaranteed, high-quality health care for all.” His Senate campaign page eventually settled on saying that we could have single-payer, or maybe something completely different. The page lists all kinds of health care policies, from incentivizing insurers to join the exchanges to creating a public option to “achieving universal healthcare coverage—whether it be through a single payer system, a dual system, or otherwise—so that we can ensure everyone is able to see a provider when it will do the most good and will deliver healthcare in the most affordable, effective way possible.” There is reason to suspect that when the time comes, it’s that “or otherwise” we’ll see O’Rourke advocating.

O’Rourke continued to do this dance with progressive issues on the campaign trail. In September of last year, a student newspaper decided to press O’Rourke on the issue of free college, which Sanders had energized a generation of Americans to back—more Republicans voters now support the idea than oppose it. The congressman said he liked the idea “a lot,” but then pivoted to some odd Clinton-esque neoliberal pitch for national student service:

I like the idea a lot. One, we know that it can predict earning potential in taxes that they pay, and two, we know it can — to some degree — predict someone’s ability to live up to and fulfill their potential. I would love for there to be some way that all of us not only receive the benefit of a great education without taking on debt, but there’s also some sacrifice made by every young American and one of the things that I’d love to work, with especially young people, on because they would be the ones that we would ask to serve is some kind of national service bill or national service program that may or may not be connected to one’s education but ensures that everyone has the chance not only to learn and succeed in that way, but to serve and to sacrifice and succeed in that way as well, so with some of the other members of Congress those two things could be connected.

It should be noted that the event was hosted by, appropriately, No Labels — the neoliberal organization which purports to be nonpartisan but loudly complained in leaked emails that Bernie Sanders was not a Democrat.

The fact that O’Rourke has inherited wealth and connections does not mean he cannot be a progressive legislator. After all, Franklin Roosevelt was incredibly rich and Goldman Sachs executive Lloyd Blankfein grew up poor. But it tells us something disturbing about American inequality that O’Rourke could sail through his 20s doing very little (except playing in a band, dabbling in business, and getting arrested), be showered with millions in donations for mouthing platitudes, and defeat a working-class Latina candidate supporting genuine progressive causes. O’Rourke’s background could also prove to be a political liability that Barack Obama did not have. Obama’s upbringing included many trials of overcoming personal adversity, and his inspiring life story—told in two bestselling books—formed a major part of the case for his candidacy. O’Rourke’s nature as a privileged son-in-law may make him a far less sympathetic candidate.

Controlling Our Elephant

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt once described human thinking as that of an emotional elephant with a rational rider. Our emotional side is the elephant, and has a great deal of control over how we feel, no matter how hard our rational side pulls on the reins.

O’Rourke’s Senate candidacy was the ultimate psychological elephant. He was well-spoken, optimistic, good-looking, and he was quick to endorse cultural memes important to the national liberal base. His eloquent defense of kneeling NFL players was an instance of him diving headfirst into a symbolic culture war controversy, ticking off all the boxes contemporary liberals look for: embrace of diversity, condemnation of racism, and describing the sins of the nation.

It’s wasn’t surprising that Ted Cruz quickly took O’Rourke’s position and used it to motivate his own base. Both sides had much to gain from rallying for something that is ultimately symbolic and emotional: Kneeling on a football field doesn’t necessarily reform the criminal justice system, and standing tall for the national anthem doesn’t necessarily do anything for the men and women of the armed forces. But both sides passionately and emotionally believed they were contributing to those causes.

Which perhaps is the best analogy for O’Rourke’s sudden popularity. He has ticked the right emotional boxes for liberals, and they feel like by supporting him they are projecting an image of a younger, more optimistic, and more progressive America. But nothing in O’Rourke’s short and uneventful political career suggests that he suddenly has the qualifications to oversee a nuclear arsenal, conduct diplomacy with friends and enemies, appoint the next head of the U.S. Treasury, or manage the disaster response of a national emergency.

The next president should be someone with a record of sticking their neck out against concentrated power, someone who has made tough decisions even when it may anger donors and political elites, and someone who has accomplished a great deal of actual tangible real change in the world. There are number of people who fit that description, but it’s difficult to say O’Rourke is one of them.

If you appreciate our work, please consider making a donation, purchasing a subscription, or supporting our podcast on Patreon. Current Affairs is not for profit and carries no outside advertising. We are an independent media institution funded entirely by subscribers and small donors, and we depend on you in order to continue to produce high-quality work.