Sci-Fi, Fantasy, and the Status Quo

How speculative fiction lost its ability to imagine alternatives to capitalism…

Last October, an intelligent and good-hearted acquaintance of mine in the SFF (science fiction and fantasy) community told me, “I just want Hillary Clinton to be queen.” She would go on to repeat this line multiple times. It was a joke—but since the Clintons are a de facto aristocratic family, it wasn’t really a joke. Most people I know in the SFF community ardently supported Hillary in the 2016 election. Many still support the Clinton dynasty, rushing to defend Chelsea whenever a leftist objects to her real lack of qualifications. In general, they stayed silent over revelations of past wrongdoing by the Clintons in Haiti, Honduras, Arkansas, and elsewhere. And they posted and reposted loving images of their exiled queen emerging from the woods.

People are of course entitled to their politics, even half-ironic liberal-monarchist politics. I don’t expect—or want—everyone I know to agree with my opinions. When it comes to SFF fans and writers, I really just want to talk about books. But of course, the political is personal, and more than personal; the political is everywhere. The political is especially present in SFF literature, which explores and attacks reality through the lens of alternate universes. If you’re a leftist who hasn’t read much contemporary SFF, you may be distressed to learn that in the last decade, much of the alternate world has been thoroughly and unpleasantly colonized by the most anemic and superficial elements of the Democratic Party.

As defined genres, science fiction and fantasy actually began as literatures of rebellion against bourgeois liberalism and capitalism. Re-told fairy tales, neo-medieval romances, ghost stories, gothic dramas, science fiction, surrealism, Romanticism in general: all these non-realistic modes were reactions to Enlightenment rationality and the stresses of industrialization. As the literary critic Rosemary Jackson writes in Fantasy: the Literature of Subversion: “The fantastic traces the unsaid and the unseen of culture: that which has been silenced, made invisible, covered over and made ‘absent’… From about 1800 onwards, those fantasies produced within a capitalist economy express some of the debilitating psychological effects of inhabiting a materialistic culture.” She continues: “… the fantastic introduces confusion and alternatives; in the nineteenth century this meant an opposition to bourgeois ideology upheld through the ‘realistic’ novel.”

Realist nineteenth-century novels were often critical of bourgeois life, of course, but they generally presented social norms as hard facts which could only be rejected so far. Fantastic literature tried alternative routes. In novels like Dracula, Frankenstein, and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, dark desires, irrational fears, and moral transgressions were physically manifested through supernatural characters and impossible events. Journeys to other worlds proliferated in the latter half of the nineteenth century, presenting thrilling scientific adventures and imaginary histories, which were lovelier—and sometimes crueler—than the slow, stiff march of liberal progress.

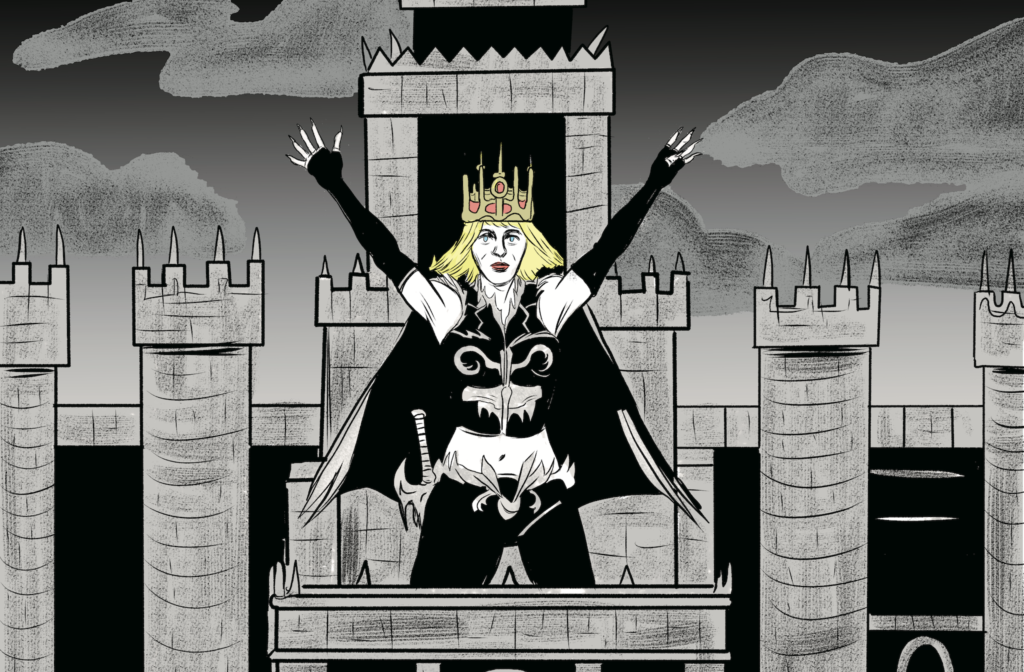

But Jackson cautions us against assuming that fantastic literature has been any kind of haven for left-wing radicalism. In fact, much of fantastic literature has been regressive and reactionary. Tolkien’s invading hordes of dark and monstrous Orcs (plus swarthy, scimitar-wielding humans) are less ubiquitous than they once were, but the glorification of monarchy is still a standard feature of SFF novels. Rightful kings and queens pop up in every wood, and they’re constantly being restored to their thrones.

Queens are particularly fashionable these days. Hillary Clinton has been frequently spliced into memes of the Khaleesi from Game Of Thrones, that very problematic white queen savior of brown slaves. There’s a bitter irony there, of course, in that Clinton once relied on black slave labor when she lived in the Arkansas governor’s mansion. In life as well as fiction, apparently, liberation—if it comes at all—will be imposed from above, and only when the white queen is ready. You’d think people would be less eager for political leaders who remind them of Game of Thrones characters, given that the Game of Thrones universe is one of utter hopelessness, in which everything is shit and getting worse. (At the time of this writing the series hasn’t ended, but it looks like the best that can be hoped for is the Khaleesi in some position of power, or living death for all as ice zombies. Talk about your lesser of two evils!)

But although most contemporary SFF is less cynical than Game of Thrones, even optimistic stories—and writers—put hard limits on political possibility and social progress, both within their fictional works and in their real-life political expression. Much of the anti-Trump #Resistance has found solace in the imagery of Harry Potter, referring to themselves as “The Order of the Phoenix” or “Dumbledore’s Army.” This too is a joke, until it isn’t a joke: a means of temporary escape from a painful reality can sometimes become reality itself. J.K. Rowling herself openly conflates the limited politics of Harry Potter with the real world, and makes ex-cathedra proclamations about how Harry (a fictional character) would or would not feel about real-life current events. According to her decrees, Jeremy Corbyn is not like Dumbledore; Corbyn, she assures us, is far too extreme. In June 2016, after Corbyn survived an attempted ouster by members of his own party and too many Harry Potter fans still had the temerity to compare him with Dumbledore, she sarcastically tweeted: “I forgot Dumbledore trashed Hogwarts, refused to resign and ran off to the forest to make speeches to angry trolls.”

But let’s look at what Dumbledore actually does—especially as relates to angry trolls—in the Harry Potter books. SFF has a long and ugly history of projecting race and class-based anxieties on inhuman Others, and Harry Potter is no exception. Rowling’s trolls are violent, illiterate morons, unfit for civilization. House-elves are stupid, adorable, natural-born servants. Goblins are hook-nosed, avaricious bankers. Centaurs and giants are noble savages, forced to wander the woods and mountains on the borders of civilization. All of the non-human species are forbidden to use wands – that is, they’re kept away from real power.

Dumbledore does express some liberal guilt for this arrangement. At the end of The Order of the Phoenix, having destroyed the fountain of Magical Brethren (“A group of golden statues, larger than life-size…Tallest of them all was a noble-looking wizard with his wand pointing straight up in the air. Grouped around him were a beautiful witch, a centaur, a goblin and a house-elf. The last three were all looking adoringly up at the witch and wizard…”) Dumbledore says, soberly: “…the fountain we destroyed tonight told a lie. We wizards have mistreated and abused our fellows for too long…”

But by the end of the Harry Potter series, precisely nothing about this apartheid-style arrangement has actually changed. Elves, goblins, centaurs, giants, and trolls are never permitted access to wands. Hermione, who was passionately devoted to “elf rights” for much of the series, settles down at the end in domestic bliss. Rowling has claimed that after the story ends, Hermione continues to fight for the rights of the downtrodden as an employee of the “Department for the Regulation and Control of Magical Creatures”. (Apparently she doesn’t fight very hard, or she would have done something about the department’s name.) In general, it’s hard to take Rowling’s non-canonical pronouncements seriously: if she really wanted elves to be free (or Dumbledore to be gay, for that matter) she could easily have written that into the text. But instead she gave us house-elves who, with a few exceptions, are more than happy to serve their masters. Ron Weasley actually says: “they like being enslaved!” Ron comes around to the notion of elf sentience eventually; Hermione marries him and apparently adopts a pragmatic approach to civil rights. Equality is a fine thing to fight for when you’re a passionate teenager, but dreams fade into incremental bureaucratic reality when you grow up, get married, and get serious.

“Getting serious” means acknowledging that power structures, as they exist, can’t be overthrown. Inequality is just one of those “hard facts” of bourgeois life. Tolkien, for all his flaws, was at least working within a mythological framework in which the desire for domination could be externalized and destroyed. But in the less elaborately symbolic, more down-to-earth universe of Harry Potter, the characters fully acknowledge the terrible injustices of race and class, resolve to “do better”—and then throw up their hands. What can imagination do against capitalist realism? At least we have an infinite variety of Bertie Botts Every Flavor Beans!

In many contemporary SFF novels, the best that can be hoped for is that a viciously unequal status quo will be reset—gently—from above. Take The Goblin Emperor (2014), an award-winning and critically acclaimed steampunk novel by Katherine Addison. Pushing back against Tolkien’s paradigm of noble elves and wicked orcs/goblins, Addison posits a world in which elves and goblins are separated only by racism. The elves (who are snow-white) consider themselves superior to the goblins (who are ink-black). The novel’s protagonist—half elf, half goblin—is suddenly thrust onto the imperial throne of the Elflands, and has to negotiate with a white court which is fundamentally hostile to him. But he’s more or less successful, and the novel ends with an expectant sense of coming racial concord. Reviewers were delighted by this progressive parable, with one person writing, “I wondered early on whether this wasn’t an Obama novel—a new ruler who is black and inexperienced coming to the capital with a will to enact change amongst entrenched and hidden enemies.” (Gee, I wonder).

I read The Goblin Emperor in January 2017, which was the exact wrong moment for its hopeful message. After all, if the best that can be imagined is getting racist aristocrats to like you, and work with you, then your imagination is insufficient—not to mention doomed to failure, as the real-life Obama presidency clearly demonstrated. But the real flaw in the novel isn’t its naivety about the swiftness with which race relations can be mended—it’s that the book’s seemingly- optimistic vision is founded on some seriously disturbing class politics.

In the narrative, the goblin emperor comes to power after someone plants a bomb on his father’s airship. This murdered emperor was a true nineteenth-century autocrat, indifferent to the suffering of the people laboring in dark satanic mills. And the terrorist bombers are true nineteenth-century political assassins—they’re anarchists, and workers from those same dark satanic mills.

They’re also completely insane.

Here’s one of the anarchists, under arrest and being questioned by the emperor:

Min Narchanezhen had the full-blood elf’s ferret face and wore her white hair in a worker’s crop. [The emperor] could tell that she was determined not to be

impressed by him; he didn’t care… “Did you know what [the bomb] would do?” It was the only question that seemed to matter.

“Yes, and I would do it again,” she spat at him. “It is the only way to force you vile parasites to relinquish your power.”… Corporal Ishilar cuffed her. “You speak to your emperor, Narchanezhen.”

“My emperor?” She laughed, and it was a horrible noise…“This is no emperor of mine… He would never know my name if it were not for the glorious strike we made against the stagnant power he represents.”… She shouted at [the emperor] as Ishilar and one of the officers from Amalo dragged her out, her voice rising and rising until it was a shriek as terrible as the wind.

Imagine a shrieking harridan so mentally ill that she spits on the divine right of kings! Min Narchanezhen is crazy – she can only be crazy. Addison could have chosen to write Min and her fellow bombers as justifiably angry—if overzealous—revolutionaries, whose violent actions spring from the real misery and injustice of their forced subservience. But the logic of the narrative says that anyone who wants too much change, too fast, and isn’t willing to wait for relief to be bestowed from on high must be diseased and hysterical. Such people are moving faster than Reason will allow. Their desire for meaningful justice can only manifest as unhinged extremism.

Novels like The Goblin Emperor are especially disappointing because they’ll go out of their way to include genuinely progressive elements—acknowledgement of inequality, protagonists of color, gay characters, heroines who persist—but consistently stop short of portraying anything resembling large-scale political or societal change. This failure of imagination is all the more distressing in a literary genre where imagination is the whole point. After all, politics may be the art of the possible, but fantasy is the art of the impossible. The visionary—and tragically neglected—science fiction writer Joanna Russ put it this way: “The actual world is constantly present in fantasy, by negation…fantasy is what could not have happened; i.e. what cannot happen, what cannot exist…the negative subjunctivity, the cannot or could not, constitutes in fact the chief pleasure of fantasy.” So why not, when writing a fantasy version of an unequal nineteenth century society, fully explore what did not happen in our actual nineteenth century? Why steampunk airships and (possible, future) racial equality, but still hideous class inequality, workers ground to death in factories, and the veneration of a “reformist” emperor?

If there are no possibilities, then there’s nothing to negate, and nothing to rebel against. A fantasy novel that simply replicates real-life political discontents—without bothering to envision how they might be solved—is a negative zero, an airless void, not an open playground in which to explore alternative modes of being. If, in both reality and fantasy, absolute monarchy is the best we can hope for against a howling darkness, then the two universes collapse into each other. The fantasy universe simply flattens into our present Reality, a dull landscape within which there is no alternative.

In general I don’t subscribe to the binary logic of contemporary criticism, where a work of art is either genius or contemptible. Up until the point of narrative failure, The Goblin Emperor and Harry Potter are intelligent, creative, stylistically interesting novels. I also don’t want to gloss over the terrific SFF novels of the last decade (N. K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth series, Nnedi Okorafor’s Who Fears Death, Naomi Novik’s Uprooted, to name a few), but these works have tended to address the fallout of regressive policies and historical crimes rather than offer alternatives. In a piece for this magazine “The Regrettable Decline of Space Utopias”, Brianna Rennix noted that dystopias have almost entirely replaced utopias in popular culture. If you want to read utopian or at least politically radical SFF, you have to go back in time. Lately, I’ve become obsessed with feminist novels from the 1970s. While arguably both dystopic and utopic, Joanna Russ’s The Female Man and Suzy McKee Charnas’ The Holdfast Chronicles at least imagine worlds in which crippling patriarchy can be defeated, or at least escaped. Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed calmly invert both gender and capitalism, showing that neither structure is inevitable or necessary.

Since the 2017 election, I’ve had a number of discussions with friends and acquaintances who are committed centrist Democrats. A few are secretly conservative and don’t realize it, but most genuinely believe that weakly defending the Maginot Line of incremental progress is as good as politics can get. This is cynicism, but it’s also despair. It comes from an inability to believe that our world can ever significantly change, at least not in a positive direction. So how do we help each other imagine a world that’s capable of significantly changing for the better? One place to start is in our dreams: that is, inside the alternate universes of fantasy and science fiction.

Ursula K. Le Guin herself has called for a more imaginative SFF literature of the future, one that envisions new worlds and new modalities of life beyond capitalist realism. In 2014, upon receiving the National Book Award’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, she gave a fiery speech, mostly taking aim at greedy publishers and the writers who permit their work to be commodified and sold “like deodorant.” But she also touched on the substance of SFF literature itself, and the imperative need—both politically and artistically—for real change. She said:

Hard times are coming, when we’ll be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope. We’ll need writers who can remember freedom – poets, visionaries – realists of a larger reality… We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable – but then, so did the divine right of kings.