Why Critical Race Theory Should Be Taught In Schools ❧ Current Affairs

The real tragedy is that there isn’t enough CRT in the classroom.

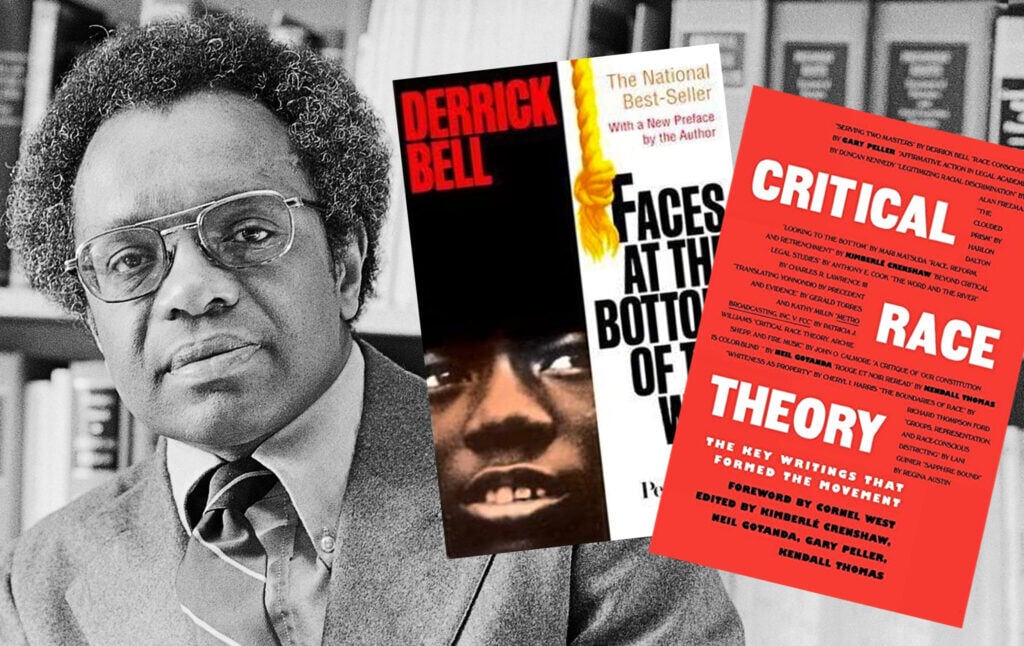

My first encounter with critical race theory (CRT)—by which I mean the original body of work, not the mythologized version that exists in today’s conservative discourse—was in college, in an Introduction to African American Studies course. As part of the curriculum, we were assigned a reading by Derrick Bell, the law professor who wrote some of the movement’s key texts from the 1970s to the 1990s. I thought it was going to be a piece of conventional legal scholarship, but it turned out to be a science fiction story called “The Space Traders.” In Bell’s story, aliens visit the United States and make a disturbing proposal: they propose to buy all of the country’s Black people. In exchange for allowing the Black population to be re-enslaved and taken to another planet, the aliens offer riches on an unfathomable scale, enough to solve every earthly problem and provide prosperity for all.

Bell’s perspective on American race relations was infamously pessimistic and (spoiler) at the end of the story, after a secret ballot referendum, American whites vote overwhelmingly to accept the traders’ terms, and the country’s Black population is carted off to the stars. The story ends with the disturbing lines:

Crowded on the beaches were the inductees, some twenty million silent black men, women, and children, including babes in arms. As the sun rose, the Space Traders directed them, first, to strip off all but a single undergarment; then, to line up; and finally, to enter those holds which yawned in the morning light like Milton’s “darkness visible.” The inductees looked fearfully behind them. But, on the dunes above the beaches, guns at the ready, stood U.S. guards. There was no escape, no alternative. Heads bowed, arms now linked by slender chains, black people left the New World as their forebears had arrived.

When I first read “The Space Traders” at the age of 18, I hated it. I felt it was ridiculous and said nothing useful about the contemporary United States. As a piece of fiction, I thought it was more than a little heavy-handed—it seemed like exactly what you expect when a law professor ventures into satirical short story writing—and wrong as a piece of social commentary. The United States would not sell its Black population to aliens. I considered myself to be aware of the workings of racism in the U.S., but I felt it operated in far more subtle ways and that Bell was being hyperbolic.

But though I disliked “The Space Traders,” I thought about it often over the years. It disturbed me in a way that lasted, and over time I realized that I had been wrong. I had objected to the idea that U.S. whites would exchange Black lives for a pile of gold, but of course that was exactly what they had already done for a good part of the country’s history, and their doing so had created inequities in wealth, health, schooling, and housing that had lasted continuously from the time of slavery to the present day.

Conceived of that way, the U.S. not only once bargained Black lives for treasure, but continues to do so. With each passing year, the country’s governing institutions allow Black people to die who could be saved, if whites were willing to expend a small amount of illegitimately-accumulated wealth. For instance: Black infant mortality is over twice that of white infant mortality. We could pay to address this problem, and relatively easily, through guaranteeing quality healthcare to all and addressing the social determinants of poor health outcomes. But we don’t. What is this but choosing money at the expense of Black lives? In other words: the despicable bargain of the “Space Traders” was not a hypothetical: it was just another way of looking at existing reality. Every dollar spent on luxury housing that is not spent on improving Black healthcare and Black schools is a deal made with the Space Traders.

It took me years to take this obvious message from Bell’s story, and I am glad someone made me read the piece. I am better off intellectually for having had to wrestle with it. It should be taught in schools. It should be thought about and argued about. It certainly shouldn’t be ignored. The uncomfortable questions it raises are ones that need facing head-on.

Derrick Bell’s body of work is unique. He famously got himself fired from Harvard Law School in 1993, when he refused to continue teaching, an act of protest against the law school’s failure to hire any Black women as professors. (In 1997, Harvard Law’s communications office told the press that it had hired a “woman of color” after Bell departed. Her name was Elizabeth Warren.) Bell’s books And We Are Not Saved and Faces at the Bottom of the Well express a bleak view of American racism, as Bell viewed the country as being deeply in denial about its racist history and current practices. The books are also not conventional works of legal scholarship or social criticism; Bell enjoyed using dialogues and fables to make his point, and as a result, the books are weird. In one Faces chapter, Bell tells a story in which all of the Black members of the Harvard faculty die in a terrible explosion. In the story, the tragedy causes the university to commit itself far more seriously to hiring Black faculty than it had ever been beforehand. Why, the story asks, do we need horrible human sacrifices in order to force important changes? (Was this speculative fiction? No. Martin Luther King’s assassination helped speed the passage of the Fair Housing Act.)

Bell was especially well-known for his unorthodox take on 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education, a court decision that was almost universally regarded as a great civil rights landmark, having formally ended “separate but equal” schooling and prohibited explicit racial segregation by governments. Bell saw Brown differently, believing that instead of merely requiring that Black children be given integrated schools the Court should have required that they be given good schools. Bell argued that Brown had created the illusion of equality and progress while doing little to meaningfully change the reality of the racially unequal provision of education. (The novelist and folklorist Zora Neale Hurston was similarly critical of Brown at the time of the decision, saying she regarded it as “insulting rather than honoring my race” because it was based on the “belief that there is no great[er] delight to Negroes than physical association with whites.”) This is not an argument against integration—the argument that “separate can never be equal” can be made consistently with it—but an argument that authentic equality requires far more than the elimination of formal separation barriers. (Bell did argue that if the court had upheld Plessy v. Ferguson’s segregation mandate but ordered actual equal provision of resources, the result would have been preferable in practice to Brown‘s approach of integration without equality, which is not a defense of the repulsive Plessy decision but an attempt to expose just how deficient Brown was.)

Bell went so far as to suggest that civil rights lawyers had actually betrayed their clients’ interests by pushing for mere integration when many of those clients cared far more about school quality. On this matter, he was blunt:

Civil rights lawyers were misguided in requiring racial balance of each school’s student population as the measure of compliance and the guarantee of effective schooling. In short, while the rhetoric of integration promised much, court orders to ensure that black youngsters received the education they needed to progress would have achieved much more.

Bell wrote that in 1976, and it’s hard not to think he was prescient when reading reports like this 2017 study which found that in the contemporary United States, “[o]nly 2 percent of African American students and 6 percent of Hispanic students attend a high performing and high opportunity school for their student group, compared with 59 percent of white and 73 percent of Asian students.” As it stands, our schools are somewhat integrated, but the worst aspects of racial inequality remain intact.

When it comes to CRT, Bell is today described as “the movement’s intellectual father figure,” who “authored many of CRT’s foundational texts.” Other legal scholars soon took up related lines of argument, filling out the body of work that eventually acquired the label CRT. These scholars, like Bell, believed that racism was a more enduring and insidious feature of U.S. life than was often acknowledged in mainstream scholarship. Their theory was critical because it interrogated and challenged prevailing assumptions. They did so creatively, sometimes through telling personal stories that helped illuminate social realities.

Pick up the book Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement and you’ll find that, while the original body of work known as critical race theory can be somewhat dry (since it was, after all, written by law professors), it’s intellectually challenging, and even exciting. For instance, one early article, Alan David Freeman’s “Legitimizing Racial Discrimination Through Antidiscrimination Law,” argues that prohibitions on discrimination actually make it harder to end discrimination, by restricting “discrimination” to new present-day acts of overt racial preference and thereby essentially sanctifying all the discrimination that has occurred up until this point and rendering its consequences legitimate. Freeman begins with a short dialogue:

THE LAW:

“Black Americans, rejoice! Racial discrimination has now become illegal.”

BLACK AMERICANS:

“Great, we who have no jobs want them. We who have lousy jobs want better ones. We whose kids go to black schools want to choose integrated schools if we think that would be better for our kids, or want enough money to make our own schools work. We want political power roughly proportionate to our population. And many of us want houses in the suburbs.”

THE LAW:

“You can’t have any of those things. You can’t assert your claim against society in general, but only against a named discriminator, and you’ve got to show that you are an individual victim of that discrimination and that you were intentionally discriminated against. And be sure to demonstrate how that discrimination caused your problem, for any remedy must be coextensive with the violation. Be careful your claim does not impinge on some other cherished American value, like local autonomy of the suburbs,’ or previously distributed vested rights, or selection on the basis of merit. Most important, do not demand any remedy involving racial balance or proportionality; to recognize such claims would be racist.”

Freeman’s article aims to account for the curious fact that “as surely as the law has outlawed racial discrimination, it has affirmed that Black Americans can be without jobs, have their children in all-Black, poorly funded schools, have no opportunities for decent housing, and have very little political power, without any violation of antidiscrimination law.” This was an early example of the kind of critical questioning that would characterize CRT scholarship, which examined how formal procedural equality was used to mask a highly unequal social reality. CRT scholars were early critics of “color blindness” rhetoric, because it deliberately ignored the reality of unequal racial distributions of wealth and power.

I don’t have space here to go through all the things I find insightful or provocative in a volume like Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed The Movement. I am just plucking the first few examples from the book. For instance: in one early piece, “The Imperial Scholar,” Richard Delgado points out how much leading legal scholarship of the 1970s and 1980s was being produced by a small number of white men at elite schools. Delgado asks whether identity should matter in academic scholarship, and concluded that it does matter, because when theory about rights and equality is being written by those who are not themselves being deprived of these things, blind spots tend to arise and result in flawed scholarship. Racial diversity in academia, Delgado shows persuasively, is not solely a matter of fairness, but is necessary for the production of better work.

The critical race theorists were very different from one another, and there is no single “critical race theory.” There is, instead, a set of works produced by academics who all put race at the center of their critical analysis of U.S. institutions, and concerned themselves with the same types of questions. Delgado and Jean Stefancic, in Critical Race Theory: An Introduction, suggest that there are some common threads among CRT scholars, though, and that “many” would agree on these propositions:

- Racism is “the common, everyday experience of most people of color in this country,” and thus “ordinary, not aberrational.” Racism “serves important purposes, both psychic and material, for the dominant group,” serving “both white elites (materially) and working-class whites (psychically).” The ordinariness of racism makes it “difficult to address or cure because it is not acknowledged.” “Formal” equality, “expressed in rules that insist only on treatment that is the same across the board, can thus remedy only the most blatant forms of discrimination” and leave basic racial inequality intact.

- Because racism is in the interests of white people, “large segments of society have little incentive to eradicate it,” which means that when seeming racial progress does occur, it is often because of “interest convergence.” Thus Black people will only get what white people see as being in their own interest to offer. (Bell’s analysis of Brown suggests that this is why actual school equality was not on the table and the focus on integration over actual equal status “may have resulted more from the self-interest of elite whites than from a desire to help blacks.”)

- Race and races are “products of social thought” and “not objective, inherent, or fixed.” While “people with common origins share certain physical traits,” the grouping of people into races is not dictated by “biological or genetic reality.”

- Identities are complicated. Delgado and Stefancic write: “No person has a single, easily stated, unitary identity. A white feminist may also be Jewish or working class or a single mother. An African American activist may be male or female, gay or straight. A Latino may be a Democrat, a Republican, or even black—perhaps because that person’s family hails from the Caribbean. An Asian may be a recently arrived Hmong of rural background and unfamiliar with mercantile life or a fourth-generation Chinese with a father who is a university professor and a mother who operates a business. Everyone has potentially conflicting, overlapping identities, loyalties, and allegiances.” The term “intersectionality” is used to describe the way these identities can converge and diverge.

- Perhaps most controversially, CRT says that people of color have a “unique voice,” because “minority status… brings with it presumed competence to speak about race and racism.” Delgado and Stefancic admit that this “coexist[s] in somewhat uneasy tension with anti-essentialism” (in other words, the experiences of people of color vary widely but there is still a presumed “voice of color” with greater credibility). The “legal storytelling” movement, they say, “urges black and brown writers to recount their experiences with racism and the legal system and to apply their own unique perspectives to assess law’s master narratives.”

Here, then, we have a set of ideas that have been defended by some who have called themselves Critical Race Theorists. And the question is: what do we make of them? Personally I think some are virtually inarguable, such as the idea that racial categories are created by human beings rather than by biology, and the idea that identity categories are complicated. Others are more debatable. For example, the idea that minority status brings a “presumed competence to speak about race” sounds reasonable in a context like the earlier-mentioned Delgado article, which was about how scholarship on civil rights had been impoverished by the fact that it was written mostly by white people who did not and could not grasp the actual experiences of being Black. And yet: there are right-wing Black commentators like Thomas Sowell and Candace Owens whose perspectives on race diverge completely from CRT. If they say that the real problem is Black culture, not racism, are their judgments “presumed competent” because of their racial backgrounds?

I think this is actually a difficult question. Because the truth is that Candace Owens does know far more about being Black than, for example, I do. And there are blind spots that an all-white group of scholars will have. But there is no unified “voice of color,” since people of color are non-monolithic. Black Lives Matter and Sheriff David Clarke could not disagree more about racism in policing. When identity and background are presumed to confer credibility or “competence,” they will often be used in pernicious ways. J.D. Vance uses the fact he grew up in poverty to give him the credibility to blame poor people for being poor. Thomas Sowell uses the fact that he is Black and succeeded as proof that other Black people could do as he did if they chose.

I think the CRT ideas above are provocative and should spark important discussions. For instance, take the idea that racism is the norm rather than the exception. Black people overwhelmingly believe that racial discrimination remains a major obstacle to Black advancement, and that Black people are discriminated against in hiring and by the criminal punishment system. White Americans are far less convinced. (But the white people who disagree should probably consider the fact that if it were the case, they would be less likely to notice it than Black people, because it wouldn’t be directed towards white people.) It seems like if we have a group of people who have historically experienced severe racial discrimination and violence, and most of them insist it is continuing to occur, and we have piles of statistics showing racial inequality across health, education, housing, and wealth, the CRT theorists’ claim that racism is an everyday fact of American life rather than an aberration should at the absolute minimum be taken very seriously. So should the corresponding hypothesis that where racial inequality does abate, it tends to do so in areas where white people’s self-interest is either helped or not harmed.

At the core of CRT, then, we have some important, if debatable, claims about the way that race functions in American life. Because CRT comes out of legal scholarship, a lot of its core texts focus on the way that racial inequality is reproduced through law, even when the law is ostensibly silent on racial questions. Is this set of ideas particularly pernicious or outrageous? No. They are plainly ideas worth teaching people about and discussing. That does not mean they are beyond criticism; a portion of Delgado and Stefancic’s book is devoted to laying out criticisms of CRT, offering responses to those criticisms, and encouraging readers to consider and evaluate the criticisms carefully. This is how it should be. We teach about ideas; we discuss them. Where the ideas are correct, we accept them, and where they are not, we critique and improve them. What we do not do is ban them from being discussed. (Yes, I believe the same about right-wing ideas.)

Which brings us to the current right-wing backlash against CRT. Republicans all over the country have been scrambling to ban the teaching of CRT in schools. Donald Trump called CRT a “sickness that cannot be allowed to continue,” issued an executive order that attempted to restrict federal contractors from trainings that incorporate concepts associated with CRT, and, more recently, published an op-ed in which he called CRT a “twisted doctrine is that it is completely antithetical to everything that normal Americans of any color would wish to teach their children” and “teaching even one child these divisive messages would verge on psychological abuse.” He said further that the left’s “indoctrination” of students in CRT was a “program for national suicide.” When he was president, Trump’s OMB director directed agencies to “begin to identify all contracts or other agency spending related to any training on ‘critical race theory,’ ‘white privilege,’ or any other training or propaganda effort that teaches or suggests either (1) that the United States is an inherently racist or evil country or (2) that any race or ethnicity is inherently racist or evil.”

Needless to say, when conservatives talk about critical race theory, they aren’t basing their opinions on a familiarity with the short stories of Derrick Bell or articles like Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw’s “Race, Reform, and Retrenchment, Transformation and Legitimation in Anti-discrimination law.” In fact, they often don’t seem to know what they mean at all. Asked to define CRT, Nebraska governor Pete Ricketts—who is steadfastly opposed to it—offered the following definition:

“So, the critical race theory—and I can’t think of the author right off the top of my head who wrote about this—really had a theory that, at the high level, is one that really starts creating those divisions between us about defining who we are based on race and that sort of thing and really not about how to bring us together as Americans rather than—and dividing us and also having a lot of very socialist-type ideas about how that would be implemented in our state.”

What I’ll say for Ricketts is that I haven’t heard any other Republican offer a more articulate definition of CRT. This is because, for the most part, Republicans haven’t read a page of the actual critical race theorists. Instead, “critical race theory” has become an umbrella term that should be understood to mean something like “All That Identity Politics Stuff I Don’t Like.” It incorporates the New York Times’ 1619 Project, the writings of Robin DiAngelo, Ta-Nehisi Coates, and Ibram X. Kendi, the concept of microaggressions, “white privilege,” and Black Lives Matter. Many on the right think there’s a conspiracy by leftists to weaponize accusations of racism in order to justify radical changes to the social order, and critical race theory is a convenient brand for the thing they detest.

Christopher Rufo, the conservative activist who has helped craft the anti-CRT narrative, has been explicit in saying that the goal is to create scary negative associations with the term, to put every incident of Political Correctness Gone Mad into the category of “critical race theory”:

“We have successfully frozen their brand—’critical race theory’—into the public conversation and are steadily driving up negative perceptions. We will eventually turn it toxic, as we put all of the various cultural insanities under that brand category… The goal is to have the public read something crazy in the newspaper and immediately think ‘critical race theory.’ We have decodified the term and will recodify it to annex the entire range of cultural constructions that are unpopular with Americans.”

“Recodifying” means that the term will no longer refer to an interesting body of legal scholarship that challenges many liberal assumptions about civil rights and racism. It will instead be a big scary evil thing that is coming for your children.

There is a stark difference, then, between how Rufo is using the term and how the term is understood by those who have long-standing familiarity with the body of work known as critical race theory. The gap in meaning was on display in a panel discussion on CRT held by the conservative Manhattan Institute, which featured both Rufo and Harvard law professor Randall Kennedy. Kennedy was a harsh critic of some CRT assertions back in the 1980s and 1990s, saying they “tend both to homogenize people of color and to segregate them from the main currents of American culture,” and Kennedy was probably invited to join the panel because of this background. (The panel did not feature any critical race theorists, probably because it is far harder to brand someone a threat to the civilized order when they’re sitting next to you sounding somewhat reasonable.) But Kennedy actually knows the literature, and seemed rather surprised when the other panelists started talking about the bogeyman version of CRT rather than the actual serious body of academic scholarship that he himself had long engaged with. When it was his turn to talk, he stuck up for CRT:

[I’ve criticized them all… But] you all spoke for a good 45 minutes as if the people who call themselves critical race theorists don’t have anything to contribute… One of the reasons why these ideas are prominent, why they are getting traction is because there’s something to them. There’s a certain strength. […] This is coming from someone who has been critical. But let’s give credit where credit is due.

Kennedy even said that the election of Donald Trump showed that on the question of whether racism was still central to American life: “I was wrong, the critical race theory people were right.” The version of CRT being described by Rufo—a neo-Marxist conspiracy to indoctrinate America’s children and destroy the country’s core values—was unrecognizable to someone who had actually engaged in the interesting academic debates over such questions as: do the law’s seemingly neutral principles function in practice to maintain social hierarchies? Is racism the exception or the norm?

But we should be careful not to lean too heavily on the argument that conservatives don’t understand critical race theory or that critical race theory bears “no resemblance” to the caricature. People like Ricketts and Trump haven’t read the literature, of course. But some of the core charges they make against CRT are perfectly true: they say that it accuses the United States of being a racist country, and they say it “rejects the fundamental ideas on which our constitutional republic is based.” Indeed, the core objection that conservatives have to what they call CRT is that it accuses white people, from the Founding Fathers to the present day, of being racist. And of course, that is indeed one of its claims. The very point of Derrick Bell’s “Space Traders” story is that white people would place their own self-enrichment over Black lives. Delgado’s “Imperial Scholar” article argues that white scholars tend to overlook the experiences of people who are not white.

It ends up being hair-splitting, then, to argue that what conservatives object to is “not really” critical race theory, which is not in fact taught in schools. They are using the term to mean things that claim white people or America in general are racist. And what we ought to focus more time on than arguing about whether something does or does not qualify as “critical race theory” is whether the particular things conservatives are trying to ban from being taught in public schools should or should not be taught in public schools.

So, let’s consider the model language that the group known as “Citizens for Renewing America” (CRA) is handing out to school boards and encouraging them to impose. The CRA proposal says its purpose is to prohibit “the teaching and promotion of critical race theory, divisive concepts, and other forms of government-sanctioned or -facilitated racism in our school district.” It then goes on to define CRT, “divisive concepts,” and “other forms of government-sanctioned or -facilitated racism.” By critical race theory, they say they mean “any theory or ideology that”:

- Derives or otherwise traces its origins or influences from, or pertinently overlaps with, the “Critical Theory” social philosophy espoused by the Frankfurt School;

- Teaches or promotes that social problems are created by racist or patriarchal societal structures and systems;

- Espouses the view that one race is inherently racist, sexist, or intentionally or inadvertently oppressive;

- Espouses the view that one race is inherently responsible for the intentional or inadvertent oppression of another race;

- One race or sex is superior to another race or sex;

- A person should be discriminated against because of the race or sex attributed to them or be treated differently based on that classification;

- A person’s moral character is determined by the race or sex attributed to them;

- The race or sex attributed to a person makes them responsible for past transgressions of that race or sex;

- A person would [sic] feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological, physical, or any other kind of distress on account of the race or sex attributed to them; and

- Work ethic or devotion to duty and obligations is inherently racist or sexist.

It defines “divisive concepts” as “any concept that espouses”:

- One sex, race, ethnicity, color, or national origin is inherently superior to any other sex, race, ethnicity, color, or national origin;

- The United States is fundamentally or systemically racist or sexist;

- An individual, by virtue of the sex, race, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin attributed to them is inherently racist, sexist, or otherwise prejudiced or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously;

- An individual should be discriminated against or receive adverse treatment solely or partly because of the sex, race, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin attributed to them;

- An individual’s moral character is necessarily determined by the sex, race, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin attributed to them;

- An individual, by virtue of the sex, race, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin attributed to them, bears responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same (or any other) sex, race, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin;

- Any individual should be targeted and made to feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress due to the sex, race, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin attributed to them;

- Meritocracy or traits such as a work ethic or devotion to duty and obligations are racist or sexist, or were created or recognized by a particular race to oppress another race; or

- The term “divisive concept” includes any other form of race or sex stereotyping or any other form of race or sex scapegoating; (a) “Race or sex stereotyping” means ascribing character traits, values, moral and ethical codes, privileges, status, or beliefs to a race or sex, or to an individual because of his or her race or sex; (b) “Race or sex scapegoating” encompasses any claim that, consciously or unconsciously, and by virtue of his or her race or sex, members of any race are inherently racist or are inherently inclined to oppress others, or that members of a sex are inherently sexist or inclined to oppress others

Finally—and I apologize for saddling you with all of this, but it’s a good idea to understand exactly what these regulations say they’re doing—“Government-sanctioned or -facilitated racism” means “any concept, theory, ideology, action, omission, custom, policy or practice enacted by elected officials or taxpayer- funded entities that”:

- Supports, promotes, or affirms the adverse treatment of an individual by virtue of the race attributed to them;

- Results in the affirmation, adoption, or adherence to viewpoints that treat individuals adversely by virtue of the race attributed to them;

- Reinforces, supports, or affirms the ahistorical and racist ideas promoted by the 1619 Project and likeminded endeavors and organizations or otherwise derives or can trace its origins to the essays, curricula, and writings of the 1619 Project and similar endeavors.

Additionally, this model language provides a long list of terms that “either wholly violate the above clauses, or which may if taught through the framework of any of the prohibited activities defined above, partially violate the above clauses.” The terms are (strap in):

Critical Race Theory (CRT)

Action Civics

Social Emotional Learning (SEL)

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI)

Culturally responsive teaching

Abolitionist teaching

Anti-racism

Anti-bias training

Anti-blackness

Anti-meritocracy

Obtuse meritocracy

Centering or de-centering

Collective guilt

Colorism

Conscious and unconscious bias

Critical ethnic studies

Critical pedagogy

Critical self-awareness

Critical self-reflection

Cultural appropriation/misappropriation

Cultural awareness

Cultural competence

Cultural proficiency

Cultural relevance

Cultural responsiveness

De-centering whiteness

Diversity focused

Diversity training

Dominant discourses

Educational justice

Equitable

Equity

Examine “systems”

Free radical therapy

Free radical self/collective care

Hegemony

Identity deconstruction

Implicit/explicit bias

Inclusivity education

Institutional bias

Institutional oppression

Internalized racial superiority

Internalized racism

Internalized white supremacy

Interrupting racism

Intersection

Intersectionality

Intersectional identities

Intersectional studies

Land acknowledgment

Marginalized identities

Marginalized/Minoritized/Under-represented communities

Microaggressions

Multiculturalism

Neo-segregation

Normativity

Oppressor vs. oppressed

Patriarchy

Protect vulnerable identities

Race essentialism

Racial healing

Racialized identity

Reflective exercises

Representation and inclusion

Restorative justice

Restorative practices

Social justice

Spirit murdering

Structural bias

Structural inequity

Structural racism

Systemic bias

Systemic bias

Systemic oppression

Systemic racism

Systems of power and oppression

Unconscious bias

White fragility

White privilege

White social capital

White supremacy

Whiteness

Woke

They have tried, as you can see, to cover their bases pretty well and leave no wiggle room. But even though this is supposed to be model language, it’s still not very clear what is actually prohibited, not because they’ve been unclear on what can’t be taught, but because they’re a little vague on what it means to teach something. They say that any employee who “direct[s] or otherwise compel[s] students to personally affirm, adopt, or adhere to” any of this will be disciplined, and students should not be “encouraged or incentivized in any manner to do so.” But they also include an exception allowing “instruction on the historical oppression of a particular group of people based on race, ethnicity, class, nationality, religion, or geographic region” and allow “primary source documents relevant to such a discussion.”

So let us say, for instance, that you put before your high school history students the following passage from W.E.B. DuBois on the way that the failure to give Black people land along with emancipation meant that slavery was effectively continued even after it was formally abolished:

The Negro voter … had, then, but one clear economic ideal and that was his demand for land, his demand that the great plantations be subdivided and given to him as his right. This was a perfectly fair and natural demand and ought to have been an integral part of Emancipation. To emancipate four million laborers whose labor had been owned, and separate them from the land upon which they had worked for nearly two and a half centuries, was an operation such as no modern country had for a moment attempted or contemplated. The German and English and French serf, the Italian and Russian serf, were, on emancipation, given definite rights in the land. Only the American Negro slave was emancipated without such rights and in the end this spelled for him the continuation of slavery.

If you began a classroom discussion on whether the failure to provide reparations at the time of emancipation was responsible for contemporary inequality, and you offered statistics on the racial wealth gap from the time of the Civil War until today, would you be in violation of the rule? Would you be “incentivizing” your students to come to the conclusion that the U.S. was systematically racist? What if you assigned a piece of Martin Luther King’s writing in which he says:

Whites, it must frankly be said, are not putting in a similar mass effort to re-educate themselves out of their racial ignorance. It is an aspect of their sense of superiority that the white people of America believe they have so little to learn.

This would seem to directly violate the rules, because King is “espous[ing] the view that one race is inherently racist, sexist, or intentionally or inadvertently oppressive.” But it is also a “primary source document” relevant to the “instruction on the historical oppression of a particular group,” which is a listed exception.

One of the problems that these laws and ordinances banning “critical race theory” may run into, then, is that “white Americans behave in racist ways toward Black people” is not a concept developed by Derrick Bell and Kimberlé Crenshaw in the 1980s. It’s an idea expressed by Black people continuously from the nation’s founding to the present day. Anti-CRT advocates should be careful, because by prohibiting theory but allowing history, they may find that the “historic oppression” of certain racial groups, if taught about accurately, uncomfortably leads to similar conclusions as CRT itself. Because theory is built from observed facts about the social world, if U.S. racism has been and is as pervasive as CRT theorists say it is, you don’t need any of the long list of terms above in order to show that. All you need are facts, so letting in “history” is opening a loophole a mile wide. Most of the 1619 Project, for instance, is based on well-documented historical fact, not theory.

Let’s be clear though on what the core of the conservative push is here: they don’t want students to hear a specific set of ideas, many of which can be considered leftist ideas. The model language suggests that even to use the word patriarchy might be grounds for disciplinary action. Same with the phrase “educational justice.” It’s not just about race, even. It’s about trying to keep left critiques out of the heads of students.

Conservatives often misunderstand those critiques, of course. The model rule defines critical race theory as meaning that “one race or sex is superior to another race or sex,” even though anti-racists entirely reject the idea of racial superiority or inferiority. But the right does know enough to know that the terms in that list are ways of understanding the world which would threaten the conservative worldview. The U.S. right does not believe that there is major racial injustice in this country. Generally speaking, they attribute racial differences in observed status to cultural and even genetic dysfunction on the part of subordinate groups—Charles Murray has just come out with another book arguing that Black people are intellectually inferior to white people. They think their beliefs are facts—Murray’s book is called Facing Reality: Two Truths About Race in America—and thus they think leftists are doing indoctrination. A defense of the truth, then, requires the purging of left ideas.

It’s important to understand that, from the perspective of conservatives, what they are doing is not a suppression of free speech. In fact, Christopher Rufo has an op-ed in the New York Post in which he vigorously contests the idea that there is anything authoritarian in CRT bans. Public schools do not teach just anything; teachers are not free to inculcate any crackpot ideas they like. States set curriculums, and banning CRT is no different from banning a course of instruction developed by the Klan:

[T]he public education system is not a “marketplace of ideas”; it is a state-run monopoly with the power of force. Even under the most dogmatic libertarian philosophy, monopoly conditions justify, even require, government intervention. The anti-critical race theory bills do not restrict teaching and inquiry about the history of racism; they restrict indoctrination, abusive pedagogies and state-sanctioned racism. […] If a public school adopted a Klan-sponsored curriculum that promoted racial superiority theory, would [defenders of CRT] support or oppose state legislation to ban it?

To answer Rufo’s hypothetical: a Klan-devised curriculum should not be implemented in public schools. But students should also be taught about the Klan’s ideology; in fact, one of the most hated “critical race theorists” is Ibram X. Kendi, whose Stamped from the Beginning: A History of Racist Ideas in America is devoted to presenting and discussing the ideas of racists. With that exhaustive CRA list of banned concepts, it would make sense to teach about these concepts, and explain why people believe them, and then also present the conservative critiques.

But one interesting feature here is the lack of actual conservative responses to the left arguments in question. Notice that the CRA’s model rule bans the very idea “that one race is inherently responsible for the intentional or inadvertent oppression of another race.” That is: it simply assumes that the inadvertent oppression of one race by another could not happen. The right does not generally respond to the left’s arguments that this did and does happen, but rather pretends the left’s evidence does not exist. For instance: I happen to have a copy of The 1776 Report, which was commissioned by Donald Trump to promote “patriotic education” in response to the 1619 Project. The report says things like “whereas the Declaration of Independence founded a nation grounded on human equality and equal rights, identity politics sees a nation defined by oppressive hierarchy.” The “principles of the American founding can be learned by studying the abundant documents contained in the record” and “show how the American people have ever pursued freedom and justice.” These include the “principle that just government requires the consent of the governed.”

The United States Constitution, of course, did not follow the principle that just government requires the consent of the governed, because women, the enslaved, and Native Americans (together comprising the majority of the country) were excluded from the process of its drafting and ratification. It was imposed on them completely without their consent. The 1776 Report provides evidence that the Founding Fathers knew slavery was wrong, in order to show that while they might not have actually granted equal rights, they at least affirmed them rhetorically. But let’s be clear: the Constitution is not an egalitarian document. It literally contains a clause forbidding states from emancipating escaped slaves. (The 1776 Report does not mention this, saying only that there were some “compromises” with slavery.) I do not think it is unreasonable to say: No person who believed in the full humanity of Black people could be proud of a document forbidding the emancipation of Black people from slavery.

What is meant by systemic racial inequality is that there has been a difference in the status of people of different racial groups continuously from the earliest days of American history to the present day. Kendi, in Stamped from the Beginning, shows that at every historical moment, ideas have been presented to justify this inequality, and rationalize the reality that white people, on average, have always had vastly more wealth and social power. Right-wing histories simply bury these facts. Instead of dealing with the arguments made by DuBois and King and Derrick Bell and Ibram Kendi and Angela Davis, they simply present them as a lunatic conspiracy theory. (Look, for example, at Rufo’s introductory description of critical race theory, which does not refute any of the claims made by sociologists, historians, economists, and legal scholars about racial inequality, but instead simply tells a story about an insidious form of neo-Marxist radicalism that threatens the country.)

Those who call the United States a racist country have arguments for why this is the case. Look at Bell’s critique of Brown, for instance: he points out that the remedy did not guarantee Black children equal access to educational resources, and because it didn’t, Black children continued to attend worse schools (on average) than white children, even if there was an effort to mix up the populations a bit through some busing programs (which were soon abandoned, and were implemented in a way that satisfied neither Black parents nor white parents). Instead of actually justifying the provision of unequal schools to people by race, conservatives simply argue that those who critique “color blind” approaches are themselves racist. You can see in the long list of ideas banned as “critical race theory” that there is a strong desire to eliminate any suggestion that white people bear any responsibility for the present-day conditions of Black people. (The logical conclusion here is that racial inequality stopped overnight in 1965, and now all lingering differences in outcome are the result of differences in self-determination. Or genes.)

Of course, it is obvious why many white people want to believe the Trumpian story of America. It was founded by good, if slightly flawed, men (such “flaws” as “imprisoning and raping forced laborers”). It has its problems, but the fundamental idea has been freedom. Nowadays we don’t look at things like identity, because that would be racist, and we are not racist. This is a pleasant story because if you believe it, you don’t have to care at all about the Black-white wealth gap, because it’s morally irrelevant. The slate is now clean, all of the historical atrocities that built that gap are long since paved over, and thus do not need to be corrected for. You can see why the right is horrified by the possibility that anyone would believe the 1619 Project: it might imply that we need to actually do something to address present-day inequalities. Much more pleasant to simply be “color blind” and accuse anyone who brings up race of themselves being a racist.

Let us stipulate, however, that there is plenty that is embarrassing about contemporary anti-racism. One reason Rufo is able to be effective in getting people mad about CRT is that he has an eye for the kinds of absurdities that are difficult to defend. For instance, one of his anecdotes:

I had one story about the Sandia National Nuclear Laboratories. They designed America’s nuclear arsenal and they had taken white male executives on a three-day retreat in the form of reeducation camp. And explicitly said, “We’re here to deconstruct your straight white male identity.” And they had the white male executives, including the chief weapons engineer of the United States, write on a white board synonyms or corollaries of white culture. And they have an image of this. They say white culture is associated with the KKK, lynching, slavery, MAGA hats, all of these mass killings, et cetera. And then they went through a process of deconstruction where they were forced to admit that whatever their outward behavior, that they had internalized white supremacy, that they were guilty of a kind of collective sin. And then they went into a kind of repentance phase where they had to write letters of apology to imaginary people of color and women and others apologizing for their privilege, apologizing for their identity.

Now, I find this silly, although the silliest thing about it is that these people build nuclear weapons, which makes it a clear example of how atrocious institutions adopt social justice posturing in order to seem like they care about justice. I think it’s fairly stupid to have white people go through self-flagellation rituals about racism, and I’ve criticized the works of Robin DiAngelo, who does these kinds of trainings that focus more on making white people feel bad than on actually exposing and trying to address the most serious racial inequalities.

In fact, many of the most absurd incidents Rufo identifies show that we would be better off if we returned to “old school” critical race theory rather than what we might more properly call Neoliberal Anti-racist Gobbledegook. Having students engage with the radical Black criticisms of liberal civil rights litigation is a useful idea. Forcing students to discuss the question of how the U.S. weights the value of certain lives over others is important. Having white students perform their guilt is less helpful, and is what led Ishmael Reed to observe that “antiracism is the new yoga.” (Reed thinks books like White Fragility are less explorations of racial inequality than “life-coaching books on how to get along with Black people.”)

Let me assume for a moment that you’re someone who thinks like Christopher Rufo, but who is perhaps operating in better faith—Rufo, after all, has essentially admitted his project involves confusing people by lumping a bunch of things together in a broad category rather than analyzing them carefully. But you are put off by a lot of the wacky stuff done in the name of “anti-racism”. Well, so am I. And my message to you is the one I have hammered over and over for half a decade of Current Affairs articles and in books like Why You Should Be A Socialist: the left is less ridiculous than we seem in the conservative caricature.

Critical race theory isn’t wacky. It’s a genuinely thought-provoking and valuable body of work. You might disagree with a lot of it, but it’s worth talking about. And because it’s worth talking about, it’s worth teaching.

Ultimately, the anti-CRT push by the right is an assault on the core of education. Whether it’s a “free speech” question is arguable (yes, public schools always have to set the curriculum in some respects, but that shouldn’t give the state absolute power to prohibit its employees from mentioning disfavored political views). But it’s certainly the case that by putting the important ideas raised by CRT theorists off the table, conservatives are committing themselves to giving children a blinkered view of the world in which challenges to the dominant ideology (“America, Fuck Yeah!”-ism) are buried, or heard about only as a sinister conspiracy theory to be fought against at all costs.

We should admit that CRT, and ideas derived from it, do what conservatives say it does: it threatens many of the notions our country holds most dear. It does that by exposing them as convenient, self-serving myths, and demanding serious soul-searching and the production of authentic equality. No wonder it needs to be combated. There are plenty who would like to maintain the lucrative arrangement they have long maintained with Derrick Bell’s “Space Traders.” There are many who would like to pretend everything is fine, and fair, and just, but it simply isn’t.